Why the UN AI Panel Must Include Marginalized Voices

Amaj Rahimi-Midani / Mar 13, 2025

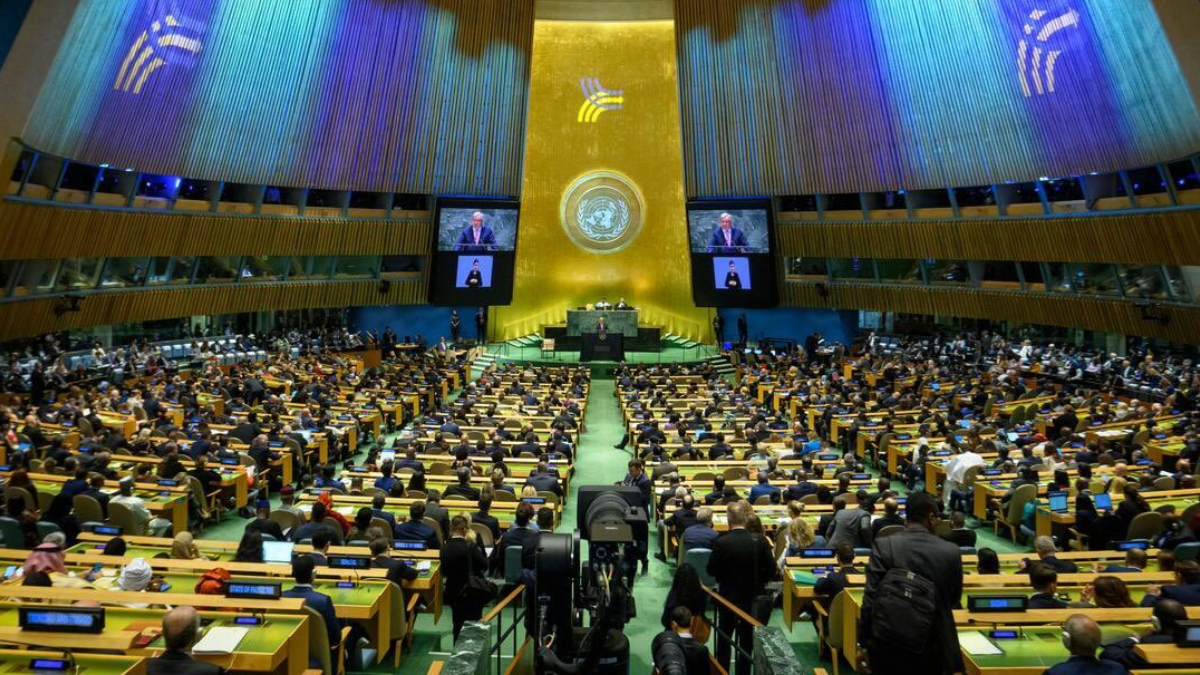

The Global Digital Compact was adopted by the UN General Assembly in New York City on September 23rd, 2024. Source

In Silicon Valley, artificial intelligence (AI) researchers debate the ethics of automation. In Brussels, policymakers discuss governance frameworks. But in rural Kenya, a farmer wonders how AI-driven agribusiness monopolies will impact his future. In the Amazon, an indigenous leader fights to preserve his people’s language, knowing AI tools could help; but they remain out of reach. The UN’s Global Digital Compact (GDC) envisions a future where AI is harnessed for the collective good of all humanity. At the heart of this vision are two transformative initiatives: establishing an Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and launching a Global Dialogue on AI Governance. To guide this process, the United Nations President of the General Assembly (UNPGA) has appointed Costa Rica and Spain as co-facilitators — Costa Rica representing the developing world and Spain representing the developed world.

On February 18, a UN-led GDC online stakeholder consultation brought together 500 participants from NGOs, the private sector, and civil society, focusing on establishing the AI panel and fostering the Global Dialogue. It was a critical step, but its success depends on who gets a seat at the table. AI is more than a technological breakthrough — it reshapes economies, labor markets, and social structures. Yet, the people most affected, particularly Indigenous and vulnerable communities, are often excluded from the conversation.

Bridging the Gap

When AI governance lacks these voices, the consequences are real. While tech hubs debate the risks of Large Language Models (LLMs), millions of Indigenous people lack access to digital tools that could preserve their languages and cultural heritage. As highlighted in Deep Technology for Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture, this lack of access extends beyond cultural preservation to critical areas like environmental monitoring and resource management. Many Indigenous and small-scale fishing communities are left without the digital infrastructure needed to collect and analyze data, limiting their ability to participate in decision-making processes and defend their marine resources against industrial exploitation. Without these tools, their traditional knowledge remains undervalued and at risk of being lost in an increasingly data-driven world. While AI investment fuels autonomous financial trading, smallholder farmers in Africa, Latin America, and Asia face the existential threat of agribusiness giants using AI to dominate markets. While policymakers discuss AI’s role in economic growth, Small Island Developing States (SIDS) struggle to leverage AI for climate adaptation and food security. Without these perspectives, AI governance risks deepening inequality rather than addressing it.

People in marginalized communities need better access to AI training and education to close this gap. AI literacy and technical skills must be strengthened within marginalized communities to enable meaningful participation in governance discussions and AI development. This includes funding for education and training programs tailored to local needs, ensuring that AI is not just developed for these communities but also by them. Universities and research institutions in the Global South need greater access to funding, research partnerships, and infrastructure to build homegrown AI solutions.

AI as a Tool for Empowerment

Beyond policy discussions, AI could be a tool for empowerment if designed inclusively. Many Indigenous communities face the challenge of having their knowledge systems undocumented and overlooked. AI-driven language models could help preserve endangered languages, capturing oral traditions and cultural heritage. AI-powered data analysis, often used to maximize corporate profits, could instead support community-led conservation efforts, real-time climate monitoring, and biodiversity protection. AI investment, which currently prioritizes high-frequency financial trading, could be redirected toward precision agriculture, food security solutions, and climate resilience strategies for smallholder farmers.

Real-world applications of AI have already shown potential to address pressing humanitarian challenges, but only when designed with inclusivity in mind. In Haiti, technology-driven solutions have been proposed to combat water scarcity and food insecurity, offering a glimpse into how AI could optimize resource distribution and crisis response if properly implemented. In Costa Rica, coordinated efforts to improve food security among indigenous students highlight the importance of digital solutions in streamlining resource allocation, a process that AI could further enhance by predicting needs and optimizing supply chains. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has also emphasized the role of digital transformation in strengthening food distribution strategies for marginalized communities, underscoring the untapped potential of AI in creating more efficient, equitable systems. These examples reinforce the need for AI governance that prioritizes local needs, ensuring that technological advancements serve as tools for empowerment rather than instruments of exclusion.

Yet even when AI has the potential to serve marginalized communities, funding priorities do not reflect that reality. Social impact funds and development banks often favor high-profile AI projects over long-term, community-driven initiatives. Research remains concentrated in elite institutions in the Global North, while funding for AI development in the Global South remains limited. For AI governance to be truly inclusive, we must rethink how resources are allocated. Funding should not only develop AI for marginalized communities but also involve them in shaping its future.

A Crucial Opportunity for AI Governance

This is why the multidisciplinary Scientific Panel on AI, currently under discussion at the UN, is so important. However, if this panel is to have a real impact, it must do more than issue reports. It must actively integrate Indigenous and vulnerable communities into decision-making processes, ensuring their voices are not merely consulted but meaningfully included. It must go beyond technical assessments to prioritize ethical, social, and environmental concerns. Most importantly, it must challenge the idea that AI governance should be dictated by those with the most resources rather than those with the most at stake.

Capacity-building initiatives should be embedded in AI governance structures. AI policy frameworks should include funding mechanisms for community-led AI projects, regional AI research hubs, and training programs that empower grassroots organizations. International bodies must move beyond theoretical discussions and commit to practical strategies that equip local communities with the tools and knowledge to shape AI’s trajectory.

Many capacity-building programs already exist, led by UN entities, NGOs, and the private sector, offering certifications, licenses, and training. Rather than reinventing the wheel, countries could leverage these existing initiatives to create a more diverse and community-based pool of experts. By recognizing these certifications as qualifying criteria, the AI panel could ensure broader representation, integrating expertise from underrepresented regions and fostering a more inclusive approach to global AI governance.

Inclusion or Exclusion: A Choose for the Future

AI governance is at a crossroads. The solutions developed in tech hubs should not dictate the realities of those living in the Global South. Governance efforts must extend beyond government negotiations to include grassroots organizations and local communities. AI should not be viewed merely as a tool for economic growth but as a force for justice, sustainability, and human dignity.

We have a choice. AI can either reinforce the same colonial patterns of exclusion that have shaped technological development for centuries, or it can serve as a force for empowerment. The outcome depends on who is included in shaping its future. The time to ensure an inclusive and ethical approach to AI governance is now.

Authors