Reactions to the Adoption of the UN Global Digital Compact

Justin Hendrix / Oct 8, 2024

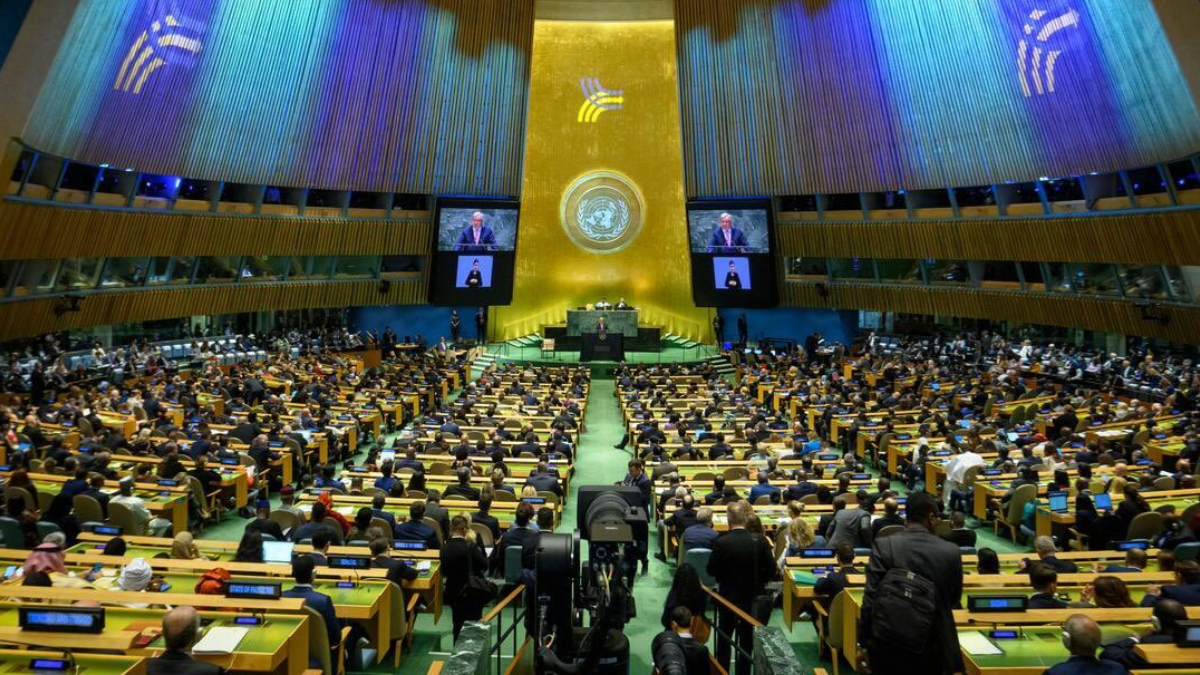

The Global Digital Compact was adopted by the UN General Assembly in New York City on September 23rd, 2024. Source

At the United Nations Summit of the Future, which took place in New York on September 22-23, 2024, leaders adopted the Pact of the Future and the Global Digital Compact (GDC) in its annex. The Global Digital Compact is billed as a "comprehensive framework for global governance of digital technology and artificial intelligence."

The GDC claims five objectives:

- Close all digital divides and accelerate progress across the Sustainable Development Goals;

- Expand inclusion in and benefits from the digital economy for all;

- Foster an inclusive, open, safe and secure digital space that respects, protects and promote human rights;

- Advance responsible, equitable and interoperable data governance approaches;

- Enhance international governance of artificial intelligence for the benefit of humanity.

The complicated negotiations that produced the final document were not certain to succeed, and close observers feared the GDC would not be adopted right up until almost the final moment. But now that the documents are adopted, what next?

Tech Policy Press invited a handful of experts from varied backgrounds and organizations to share reactions to the GDC and the process that produced it, and to share their thoughts on what it will mean going forward. We received contributions from:

- Alison Gillwald, PhD, Executive Director of Research ICT Africa

- Konstantinos Komaitis, Senior Resident Fellow, Digital Governance Lead, Democracy and Tech, Atlantic Council.

- Rebecca MacKinnon, Vice President, Global Advocacy at the Wikimedia Foundation

- Jan Rydzak, PhD, Digital Transformation Lead at the World Benchmarking Alliance

- Barbora Bukovská, Senior Director for Law and Policy at ARTICLE 19

- Lauren Compere, Managing Director and Head of Stewardship & Engagement at Boston Common Asset Management

- Timo Harakka, a Member of Parliament in Finland

What follows are their lightly edited responses.

Alison Gillwald, PhD, is the Executive Director of Research ICT Africa:

Although the final version of the Global Digital Compact saw a significant erosion of principles of equity, redress and commitments to international solidarity funding beyond AI, it is perhaps a triumph that sufficient consensus was reached with current geopolitical tensions and political polarization to have anything to take forward at all.

Flawed as the GDC is, it remains our only hope of mobilizing the global cooperation required to redress widening digital inequalities and harness technological innovations for humanity.

Problematically, the framing of the Compact, as with the AI for Humanity report released by the Tech Envoy at the Summit of the Future, perpetuates notions of tech solutionism to deep-rooted human problems. Both fail to acknowledge the deepening structural inequalities that are being amplified by intensifying global processes of digitalization and datafication.

Without this recognition, the Compact will be unable to solve the wicked policy problem that resulted in its call–the digital equality paradox. Unlike with traditional telecom, the divide is not only between those online and offline but between those who have the technical and financial resources to optimize access to the Internet and OTT era and those who are barely online, without the resources to realize the benefits of access, to improve their livelihoods, never mind innovate or contribute to the prosperity of nations. The lack of digital participation by most people, certainly Africans, renders them invisible, underrepresented, and discriminated against in the giant data sets of advanced data-driven technologies, and this cannot be corrected by frameworks ‘responsible and ethical’ AI.

Time will tell whether the Compact's guts are sufficiently transformative to stave off the dire outcomes of compounding digital inequality without global intervention, which the Secretary-General warned of when he called for it in the context of the pandemic and post-pandemic economic reconstruction.

Much will depend on how innovatively the more practical implementation and monitoring mechanisms, fortunately mandated in the Compact, are deployed. This will depend on how willing those responsible for instituting them are to disrupt dominant interests and tackle foundational digital inequalities underlying not only the uneven distribution of harms, but also of economic opportunities associated with advanced data-driven technologies.

Konstantinos Komaitis is a Senior Resident Fellow, Digital Governance Lead, Democracy and Tech, Atlantic Council:

There is a new abbreviation to the Internet governance alphabet soup–the GDC, or the Global Digital Compact, is the latest attempt to address key issues of digital governance. It is part of the Pact for the Future, an effort driven by the UN Secretary General’s to revitalize the multilateral system through a series of issues, including space, international peace and the transformation of global governance. It was meant to bring governments and stakeholders together towards addressing some of the world’s biggest challenges. The GDC, which is annexed to the Pact, provides a new reality for (multilateral) digital governance.

What this new reality means is still unclear. There are sections in the GDC that could prove useful, but, in the end, the GDC tried to do too much too fast. The lack of an effort to tie the GDC into pre-existing processes meant that member states came in with almost a blank sheet. During the negotiations, everything seemed to be on the table–from the way the internet should be managed to how human rights should apply and what role multi-stakeholder participation should play in the future of digital governance. The lack of collaboration between member states resulted in a text that is weak and vague–it is weak on human rights, weak on internet governance and weak on connectivity. What is more, the GDC authorizes a whole new set of processes and organs, which indicates that, over the next few years, the debate on the future of the internet will move deeper into the UN machine. No one knows what these new things will actually do; what we know is that they will live within the UN. This will both challenge and put pressure on the normative multi-stakeholder framework and jeopardize how we will all get to participate in shaping our digital future.

For now, the pressing question is what role the GDC will play in the forthcoming World Summit on Information Society (WSIS)+20 Review, slated to take place next year. WSIS is important for many reasons: its agenda is focused on development and it is tied to the internet and technology in general; WSIS recognizes that the best way to govern the internet is through bottom up coordination, collaboration and inclusion; and, it also establishes the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), the only space within the UN system that shows governments’ pledge to the multi-stakeholder system. These are important properties coming out of WSIS, and they have defined the past twenty years of digital governance. In this context, the follow up and implementation of the GDC is critical as it will determine how the GDC will interact with the WSIS+20 review. Will the GDC subsume the review, diluting its focus and importance? Will WSIS end up supporting the GDC and its implementation?

It is for this reason that, going into the WSIS+20 review, we must come prepared. A quick rundown on how the GDC played out suggests the following: throughout the GDC negotiations, China and the G-77 group showed an impressive, united front recommending a more state-driven approach to the governance of digital technologies. The Secretary General’s Office of the Tech Envoy is the new kid on the block and it is here to play. The Office will have general digital governance coordination functions, but so far it is highly unclear what gap it seeks to cover. Digital issues are at the top of member states’ agendas and, to some of them, it is even part of their foreign policy; this changes the nature of all future digital governance discussions. And, finally, the WSIS consensus is no longer present.

Next year will be perhaps the most critical in the history of internet governance.

Rebecca MacKinnon is Vice President, Global Advocacy at the Wikimedia Foundation:

The concept of the Global Digital Compact was ambitious. It spelled out commitments about the future of digital governance that incorporated the perspective of a wide array of government and non-government stakeholders, but remained broad enough to be adopted unanimously by Member States. While this has resulted in the welcome inclusion of terms advocated for by civil society, it has also necessarily meant that the resulting text is quite broad. Only when governments, industry, and civil society begin to implement the commitments in the Compact will the details be fully realized.

For example, throughout the Wikimedia Foundation’s engagement with the Compact process, in cooperation with key national-level affiliates and allied NGOs, we have have emphasized the importance of recognition and support for Digital Public Goods (DPGs) in the Compact. According to the Compact, DPGs include “open-source software, open data, open AI models, open standards and open content.” DPGs are critical for a healthy information ecosystem. They must be nurtured in order to ensure everyone, everywhere can share and access knowledge. It is encouraging to see the inclusion of commitments in the final Compact to support DPGs as well as the related concept, Digital Public Infrastructure (known as DPI, which is, as with much of the text, defined at a very high level).

Over time, in order to make more concrete the commitments in the Compact, there will have to be further conversations defining these concepts. Clarifying that government support for DPGs must include projects, platforms, and technologies that support independent, open civic space is vital to the future of the digital commons and free knowledge.

It is critical to ensure that governments’ support for the DPGs imagined in the Compact will not result in a top-down, narrow approach that could result in government and/or corporate control of digital public services. Similarly, the commitments in the Compact to ground policymaking in international human rights law and to multi-stakeholder internet governance are positive steps, but will really only be tested upon application. Much of the work to shape the ideas contained within the Compact is still to come, and in this phase we would love to see more transparency in the way stakeholders are involved in the conversation.

Many questions that were raised during negotiations for the Global Digital Compact, however, remain open. For example, while the final text highlights multi-stakeholder partnerships as critical for global digital governance, some Member States where civic space is not protected have an interest in pushing for top-down and multilateral models of internet governance that do not include non-governmental stakeholders. It will be up to the UN and the majority of Member States to ensure that the spirit of the Compact is respected in this regard.

To this aim, we co-organized a side event about DPGs at the United Nations Headquarters on the eve of the UN General Assembly, bringing together representatives from all these groups to share their perspective on the benefits of supporting digital commons and DPGs which are created and maintained by grassroots communities, like Wikipedia. Panelists argued that the digital divide can only truly be bridged for marginalized and vulnerable communities - and linguistic and cultural diversity can only be preserved online - when the definition of DPGs include community-led public interest platforms, as opposed to top-down, government- or for-profit solutions. While it remains to be seen how governments will implement the commitments in the Compact, it is vital that steps toward its fulfillment involve the active participation of the same stakeholders who helped shape it.

Jan Rydzak, PhD, is Digital Transformation Lead at the World Benchmarking Alliance:

Two years, four revisions, and one last-minute derailment attempt later, the UN General Assembly has finally adopted the Global Digital Compact. Threaded between more than a hundred state commitments are ten soft commandments for tech companies. They represent specific calls for the titans of the modern Internet to do their part toward fulfilling the GDC’s ambitions.

In order of appearance, the ten commandments are as follows (edited for brevity).

1. Apply the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

2. Respect international human rights principles and apply human rights due diligence throughout the life cycle of tech products.

3. Respect human rights online while mitigating, preventing, and remedying abuse.

4. Engage with users of all backgrounds and incorporate their needs.

5. Co-develop industry accountability frameworks that increase transparency and define responsibility.

6. Provide online safety materials and safeguards, especially for children and youth.

7. Establish strong reporting mechanisms for policy violations.

8. Enhance the transparency and accountability of companies’ systems.

9. Provide researchers with data, especially on misinformation and hate speech.

10. Develop and communicate ways to counter the risks and harms of AI.

Does Big Tech have enough reasons to care? Do we?

Most of the ten appeals are laudable. The first three all reference international human rights frameworks as well as the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, one of their most celebrated artifacts. The anchoring, then, is strong. More glimmers of progress emerge whenever one of the calls packs in some precision. For instance, the GDC couples the vague invocation for tech giants to “enhance the transparency and accountability of their systems” with specific areas they should prioritize. Among them are transparent terms of service, strong content moderation structures, and informed consent. Layers of ambiguity still underpin all these terms, but embedding them in a major international agreement helps normalize the ideas behind them.

There are more dubious moments in the final draft. One of them is the call for the tech industry to “co-develop industry accountability frameworks.” This lands like a an appeal for self-regulation toward an industry with a checkered history and few incentives to self-regulate effectively. The Freudian slips of AI’s corporate boosters inspire little hope for high standards of practice if tech companies get to define their own responsibilities.

Is there a leading role for the GDC in the future of tech accountability, or will it settle for a fleeting cameo? To me and my colleagues who scrutinize what tech companies say and do, it’s a step forward. A high-level pact with a flurry of commitments equips us with a tool to put pressure on companies in areas where they too should be held accountable. It can also offer new openings for the tech industry itself. After all, a new intergovernmental pledge to refrain from internet shutdowns gives network operators something to bring up whenever they face pressure to cut millions of people off from the world.

The GDC alone probably won't mend the frayed fabric of the internet. But it’s a rallying point whose success hinges on how we use it. While it falls short of spelling out clear consequences for corrosive corporate behavior, prudent regulation and collective action can make it consequential.

Barbora Bukovská is Senior Director for Law and Policy at ARTICLE 19:

Among its "pros," ARTICLE 19 finds the Global Digital Compact as an opportunity for the UN and member states to reaffirm and prioritize human rights in the digital sphere, address the digital divide, and promote a multi-stakeholder approach to digital governance. We commented on the Compact's focus on integrating existing international human rights commitments and its aim to promote universal connectivity, potentially democratizing access to digital resources and reducing global inequalities.

However, on the "cons" side, we cautioned against duplication with existing processes at the UN and beyond touching on digital governance. We have also emphasized the need for clear implementation strategies to address complex issues such as private sector responsibilities, content moderation practices, and tackling disinformation and hate speech without infringing on fundamental rights.

The GDC, as part of the Pact for the Future, is a non-binding agreement. This limits its enforceability and may reduce its effectiveness in ensuring countries and the private sector adhere to its principles.

Lauren Compere is Managing Director and Head of Stewardship & Engagement at Boston Common Asset Management:

As investors, we actively seek opportunities to invest in a broad range of companies that are part of the AI ecosystem, from chipmakers, software, and platforms to telecoms. We are also well aware of the negative risks and impacts to people and planet this poses—many of which are not anticipated as part of Generative AI.

Simply put, investors can and do play a critical role in ensuring corporate accountability in the development and deployment of AI. As a co-lead and founding investor of the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) Ethical AI CIC since 2022, we have partnered with 50 investors, engaging 75 companies on ethical AI practices. This includes ensuring companies assess risks and impacts across the value chain of AI development and deployment, mitigate them through robust AI governance, human rights due diligence processes, and inclusive stakeholder engagement, and provide access to grievance and remedy mechanisms.

With its adoption at the UN during the Summit for the Future, the Global Digital Compact (GDC) establishes the first global governance framework for AI design, use, and governance for the benefit of all. It embeds human rights and international law, prioritizes online child safety, and has agreements for making data more open and accessible. Our ability to ensure corporate accountability is much more effective with the Global Digital Compact in place–when global frameworks become global norms, investors are then able to back a standardized set of asks. This has clearly been successful with other global frameworks, UNGPs, the Paris Agreement, and the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Much of what the GDC calls companies to do mirrors and re-enforces what investors are already asking for. How it evolves and is adopted by governments will determine how effective it is. One area of potential concern is the call to companies to co-create accountability mechanisms. While co-creation and partnership are important, companies should not lead in establishing their own corporate accountability mechanisms; governments and civil society should. Investors should step up to play a key role in supporting the success of the Global Digital Compact and its effective implementation across the markets they invest in.

Timo Harakka is a Member of Parliament in Finland:

The Global Digital Compact was the most concrete part of the UN Pact for the Future, underscoring the notion that bridging the digital divide is one of the most urgent tasks of the multilateral world order – should, indeed, the world order remain multilateral in any real sense.

I commend the work of the Secretary General´s Advisory Board on Artificial Intelligence, a significant contribution to the Compact. Under the leadership of Carme Artigas and James Manyika, the multi-stakeholder, multinational group produced a very useful report in record time, in less than a year.

Establishing an Independent International Scientific Panel on AI, modeled after the IPCC – the first recommendation of the Advisory Board – is urgent and necessary. Immediately upon the adoption of the GDC, international AI experts led by Professors Yoshua Bengio and Alondra Nelson agreed on core principles of the Panel in the “Manhattan Declaration,” of which I also am a signatory.

The IPCC has been invaluable in establishing a scientific consensus on climate trajectories and consequences thereof, thus providing the factual common ground for us policymakers around the world. I hope the AI Panel will be similarly successful in laying down science-based assessments of the progress of artificial intelligence, real risk probabilities and policy advice. We certainly need a credible global authority to curb both overly optimistic and dystopian extremes, and to help build a beneficial international AI regime.

Authors