Evaluating the UN AI Advisory Body Interim Report

David Kaye / Feb 14, 2024David Kaye is a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, and 2023 – 2024 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Public International Law at Lund University, Sweden.

Late last October, United Nations (UN) Secretary General António Guterres announced the formation of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Advisory Body, bringing together thirty-nine people from around the world from industry, government, academia, civil society organizations, and elsewhere. A mere two months after its formation, on December 21, 2023, the Advisory Body released a thirty-page Interim Report that seeks not only “to analyze and advance recommendations for the international governance of AI” but to identify and claim a role for the UN. The speed of the report’s delivery certainly says something about the moment, following a remarkable few months of global competition for leadership over the regulation of AI, efforts that generally excluded explicit reference to global norms. Among the leading examples of the regulatory fever, such as the European Union’s AI Act, China’s AI initiative and regulation, the United Kingdom’s Bletchley Declaration, the G7’s AI Process, and the United States’ Executive Order 14110, only the Council of Europe’s draft AI treaty is expressly founded on norms of international law.

In a crowded, elbows-out regulatory environment, it can be difficult for the ‘excuse-me-pardon-me’ soft power approach of the UN to compete with domestic and regional legislation and treaty-making. For one thing, why should states, civil society organizations, academics and companies care about the UN’s role, given that so much of the action is taking place in executive bodies, legislatures and corporate boardrooms around the world? What is missing that the UN can provide? Beyond that, even if there is agreement that the UN can play a useful role, what should it look like? Should it take on a coordinating function given the varying approaches to regulation? Should it develop institutions to do that work or instead rely on existing UN bodies to adapt the rules already binding on states and private actors? Should it create models of best practice that states can or should apply in their own domestic and regional settings? Or should it just be a kind of global scold, wagging its finger at the companies and states building and deploying tools destined to have massive impact on society, politics, climate, education, human rights and everything else under the sun?

These questions (or questions quite like them) form the backdrop for the Advisory Body’s Interim Report. The Advisory Body answers them by making a case for global governance of AI and proceeding to outline sets of principles that should guide that governance and institutional functions that could bring the principles into effect. The Report toggles between sharp insights into the opportunities and risks of the current AI environment and general propositions about how to address them. The Report is very much interim, a halfway house on the road to a final report later this year and its presentation to the UN’s Summit for the Future late in the summer. Many of its insights are exciting to read in a UN document, but the real value of the Advisory Board’s work remains to be seen, particularly in whether its final report will be willing to take its insights to their logical conclusions – or hesitate in the face of undoubted resistance by the most powerful in today’s AI universe.

What does the UN bring to the table?

The Advisory Body begins at the right place, emphasizing that the UN’s value to AI governance comes from “the rules and principles to which all of its member states commit.” The UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international law more generally, the institutions created for such purposes: these are the foundations of the UN’s role. Moreover, the Advisory Body argues, the UN allows for “a more cohesive, inclusive, participatory, and coordinated approach” than current efforts have allowed, especially its ability to involve the Global South. This is a strong and perhaps obvious basis for UN engagement. The current regulatory efforts are taking place in the most powerful capitals, often influenced by some of the most powerful players in the industry. Do these efforts provide any guardrails to protect those outside their jurisdictions? The question answers itself; where Western and Chinese regulatory efforts may seek to protect themselves and their interests, they do not speak to the impact on those beyond, whether in the context of lost opportunities and increasing AI divides or the labor and resource harms that may fall disproportionately on those in the Global South. The Report’s focus on those beyond the center of AI innovation and regulation is noteworthy and vital.

Power disparity is a persistent theme at the outset of the Report, a foundational assessment of a problem that “global governance” is meant to solve. Simply put, the Advisory Body sees economic, corporate and political power over AI technologies concentrated in “a small number” of actors while AI’s harms are “unevenly spread.” There is disparity in ownership, knowledge, regulatory impact, compute (a jargony term used throughout the document to refer to computing power and capacity), talent and other resources. In light of this power-harm disparity, the Advisory Body makes this basic pitch for a UN role:

Global governance with equal participation of all member states is needed to make resources accessible, make representation and oversight mechanisms broadly inclusive, ensure accountability for harms, and ensure that geopolitical competition does not drive irresponsible AI or inhibit responsible governance.

This is ambitious language – and a heavy lift for the UN, particularly at a moment when its political bodies are riven by crises and key institutions likely to offer meaningful support are badly under-resourced. Moreover, historically Western powers have objected to this kind of resource-distribution demand, and there is nothing in the politics of the moment to suggest they have suddenly become adherents to the kind of transnational assistance and capacity-building promoted by instruments like the UN Charter or the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Yet the Advisory Body pushes ahead. Early on the Report seems to welcome industry “self-regulatory initiatives” and legal efforts at national, regional and multilateral levels, a potential nod to corporate-friendly regulation. But this seems to be retracted when the Report later notes, “in many jurisdictions AI governance can amount to self-policing by the developers, deployers, and users of AI systems themselves.” It adds, “Even assuming the good faith of these organizations and individuals, such a situation does not encourage a long-term view of risk or the inclusion of diverse stakeholders.” The Advisory Body offers a call not for self-regulation, but rather regulation in the public interest.

What principles should guide AI governance?

With its diagnosis of the core problems set out – power concentration and uneven harm diffusion – the Advisory Board is ready to turn to the forward-looking aspects of its work. As such, it presents a set of five “guiding principles” and seven potential “institutional functions.” The guiding principles are at a high level of generality and will need to be articulated further to have operational value for further UN work. They are: (1) inclusivity; (2) public interest; (3) data governance and “promotion of data commons”; (4) universality, “networked and rooted in adaptive multi-stakeholder collaboration”; and (5) an anchoring in international law and the Sustainable Development Goals. At the moment, these principles are somewhat abstract for actual governance, and the recitals that support the principles are occasionally difficult to decipher. This is not meant to be a harsh criticism; the work was obviously done quickly, pushed forward by the indefatigable UN Technology Envoy, Amandeep Singh Gill, and so readers should, it would seem, take the language as a starting point rather than a final landing. That said, the principles, as they stand, require further work to clarify exactly what they intend to accomplish in terms of norm-building and governance.

Take, for example, the third principle, that “AI governance should be built in step with data governance and the promotion of data commons.” “Data is critical for many major AI systems,” the Report notes, which is obviously true. It then adds a bit of jargon, with caveats that demand multiple readings to capture an otherwise elusive understanding: “Regulatory frameworks and techno-legal arrangements that protect privacy and security of personal data, consistent with applicable laws, while actively facilitating the use of such data will be a critical complement to AI governance arrangements, consistent with local or regional law.” It seems to recognize the existing clash between privacy and security of data, on the one hand, and access to data, on the other, without providing a formula to resolve it. The final report will need to take a position given the importance of this issue. Let’s put it this way: If a governing authority faces a choice between data security and privacy and use of such data in an AI system, what principles should guide the outcome? From what criteria should governance authorities draw? Should the decision be driven by, for instance, human rights concerns (such as the right to privacy or freedom of expression) or the drive toward AI innovation? Or, what if the outcome has security implications? Who decides the outcome?

Similarly, the language of the fourth principle sprinkles bits of insight with management-consultant speak, ultimately avoiding the essential question of what multistakeholder governance should look like in the AI context – if it has a role to play at all. It says, for example, that AI governance “should prioritize universal buy-in by different member states and stakeholders.” Does it mean universal buy-in by all states and all stakeholders? By some majority of them? Such governance should enable participation by those in the Global South, it says, but its reasoning is unclear, as the Report says that AI regulations need to be “harmonized in ways that avoid accountability gaps,” without explaining what principles might guide considerations of duties, liability, reparation, and so forth. It proposes that “new and existing institutions could form nodes in a network of governance structures,” for which there is momentum, the Report claims, along with “growing awareness in the private sector for a well-coordinated and interoperable governance framework.”

It should be unsurprising that industry wants interoperable and coordinated regulation, but is that reason enough for it? Might diversity in regulation, developed for the particular contexts faced by about 190 state jurisdictions, be an appropriate response even if that makes it more difficult for industry to develop AI tools and exploit the data to which it seeks access? What does interoperability mean in a context divorced from its traditional technical role (i.e., enabling diverse technical systems to work with one another), and what does it have to do with “adaptive multistakeholder collaboration”? The Report says that “[c]ivil society concerns regarding the impact of AI on human rights point in a similar direction,” but not only is this debatable – might not civil society prefer human rights protection over interoperability and coordination? – it is also not clear in what direction it refers. Beyond all of this, it is important to note that the principle on its face is not proposing multistakeholder governance as a model, the way it has helped drive and support global internet governance, but rather multistakeholder “collaboration” – a very different and perhaps less meaningful idea.

The fifth principle promises much, and the Board’s inclusion of it deserves praise by those who hope that AI governance is rooted in international law. In some respects, it could have been the first principle, providing a foundation for everything else. Critically, it proposes that international law serve as a bulwark to ensure that the presumed future of AI dominance does not destroy every other principle of international governance. As it stands, however, it requires much more articulation. The final report, for instance, will need to make clear that when it refers to the Charter and human rights law, it means to reinforce existing institutions that protect these norms, especially the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR). Surprisingly, OHCHR is not mentioned anywhere in the entire report, even though the High Commissioner and the Human Rights Council’s Special Procedures (see, for example, here and here) have done significant work on AI and human rights law (including, I will add, my own work in 2018). Moving forward toward a final report, the Advisory Board will have to be clearer about the international legal standards at issue, the role that human rights law and its mechanisms ought to play in global AI governance, and the particular ways that the UN Charter’s promotion of peace and security and sustainable development relate to AI governance. As of now, that clarity is absent, but the placeholder is important and deserves prioritization in the Advisory Body’s future work.

What governance functions must be operationalized?

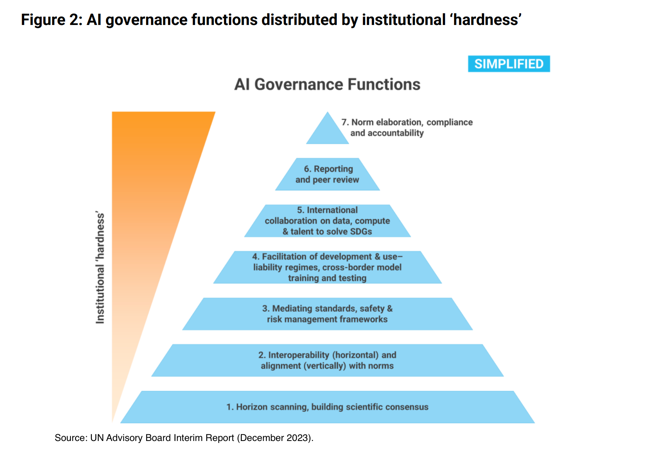

After highlighting these principles, the Report proposes a range of functions that “an international governance regime for AI should carry out” – without weighting the scales by indicating which would be advisable at this time. They are aspirational in that sense. Here the work operationalizes its principles along an axis of “institutional hardness” (a term it does not define but which seems to move from “soft” to “hard” law – from assessment and monitoring to compliance). The Report summarizes seven governance functions in the following pyramidal scheme:

A figure from the Interim Report.

The functions extend from a basic assessment role (Function 1), similar to the kind of “knowledge and research” work done by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), all the way to a “compliance and accountability” role founded on “legally binding norms and enforcement” (Function 7). In between lies the range of other potential institutional functions: the reinforcement of “interoperability of regulatory measures” (Function 2); the harmonization of standards and “risk management” (Function 3); the facilitation of AI use particularly by communities in the Global South (Function 4); the promotion of collaboration of all kinds across borders, including “expert knowledge and resources” (Function 5); and risk monitoring and emergency response (Function 6).

Grading the Interim Report on problem definition

The Advisory Body’s Interim Report deserves a wide reading. It also deserves to be evaluated on the basis of its own diagnosis of the problem. As noted, the Report begins with a fundamental power disparity – a concentration of power, resources, data and much else in a small number of companies and states – and a concomitant “uneven” distribution of harms. So the first question might be: does the Report meet the challenge it sets up for itself? Does it lay the groundwork for a final report, along with concrete recommendations for the Summit for the Future, that appropriately tackles power and harms? At this stage, the jury must still be out – it is only fair to judge a self-identified “interim” report according to its propositional characteristic. That said, in order for the final report to meet the very challenge the Advisory Body sets up for itself, it will have to achieve at least the following objectives:

First, its theory of change to address the power concentration problem needs to be better articulated than it is now. There are too many inconsistencies that cut against one another at the moment. For instance, if concentration is the problem, why is interoperability the solution? Why might regulatory diversity not be an answer? It may very well be that regulatory harmony across borders will be a requirement for AI’s success. But if I am a legislator or regulator in Country X, with a particular approach to data protection and resource development, why must my AI governance regime be ‘interoperable’ with that of Country Y, which has a very different approach to the same issues? What value, apart from predictability for multinational corporations, does that kind of harmonization serve? Institutional Function 3 emphasizes the importance of harmonized standards but neither it nor the Guiding Principles genuinely explain the underlying reasons for it. Perhaps harmonization has a basic human rights or SDG purpose, but if that is so, the Advisory Board should spell it out so that stakeholders understand why that should be an objective.

In keeping with the concentration diagnosis, the Report, to its credit, notes the need for infrastructural investment (e.g., “talent, data, and compute resources”), training of “local models on local data,” and even international assistance and cooperation, governmental and corporate, in order to enable broad sharing of AI’s opportunities and benefits. It also proposes “federated access to the fundamentals of data, compute, and talent . . . as well as ICT infrastructure and electricity,” alluding somewhat cryptically to the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) model of distributing scientific benefits globally. These are sound ideas, but they also need a theory for how such sharing, first, can be accomplished – would it require regulatory command or simply state-supported “incentives”, whatever those might be? – and second, can be enforced across borders. With power concentration centered in the Advisory Body’s work, it is puzzling that the report does not surface the possibility of competition policy, or antitrust, as a framework for addressing this foundational problem. This too is something the final report should address.

Second, the Report’s assessment of uneven harms is a critical marker for future work. While admitting that compiling “a comprehensive list of AI risks for all time is a fool’s errand,” it nonetheless notes some of the real and current risks of unregulated AI. It puts into that category discrimination, disinformation and manipulation, the problem of experimental technologies let loose upon the public, weaponization (as in autonomous weapon systems), and privacy-busting surveillance, facial recognition and other data-hungry threats. The Report does a real service to the current debate, which has framed so much of AI technologies in terms of science-fiction, civilization-ending tools. As the Advisory Board moves toward a final report, it will have to grapple with the reality that harm-identification is not enough. It will have to propose a governance framework that addresses particular kinds of present and foreseeable harms.

In fact, this is an opportunity for the Advisory Board to connect and better articulate its guiding principles to institutional function. For instance, given the vagueness that plagues principle 5 (the role of international law), the Advisory Board should identify some very specific human rights harms and articulate how international law serves to prevent, mitigate and/or remedy them. Thus, as the final report will come in the midst of a historic year for elections around the world, the Advisory Body could usefully grapple with the problem of AI tools used for electoral disinformation, identifying the norms of international law at issue and the mechanisms potentially available to states and to international bodies to address them.

Election disinformation is just one example; one could take any of the other examples and propose a framework of law and enforcement, even drawing on existing institutions like human rights treaty bodies and, as the Report mentions in passing, the Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review, to address them. It could (and should) draw from the hitherto uncited UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to articulate the way states have obligations to address harms caused by private actors – and how private businesses have responsibilities to prevent and mitigate human rights harms. At the same time, the failure of the Interim Report to refer even once to OHCHR is glaring, given that it, alongside the Human Rights Council, is at once the most significant entity within the UN for human rights norm-development and enforcement, and is also among its most poorly resourced institutions. The Advisory Body should press for a central role for OHCHR and its associated bodies in the attempt to address AI harms.

It is also worth noting how little attention is paid to environmental impact. The issue makes a late appearance in Institutional Function 3, in the context of standards and indicators, but generally speaking the Report does not grapple with the climate change consequences of increasing demand for computing power and energy resources, as well as the environmental and labor issues surrounding the mining of rare earth minerals. In some respects, AI presents an opportunity for climate change solutions, as an early case study in the report suggests. But AI technologies’ thirst for energy also poses a severe challenge to the UN’s commitment to addressing climate change. At the very least, an Advisory Board focused on harms should address this evident conflict.

As a third and final comment, there is a looming question over just what the Advisory Body expects to propose for multistakeholder governance. The Interim Report includes several favorable references to multistakeholder cooperation and collaboration, and its reference to critical bodies in other fields – such as the IPCC for climate change or the CERN for the dissemination of science – should be welcomed. Still, the AI context requires further development. In particular, several categories of non-state actors must be part of the discussions around AI governance if the kinds of solutions the Advisory Body envisions are to be effective. It will be important to do more than emphasize the role of civil society organizations, technical experts, academic institutions, human rights defenders, standard-setting bodies; the Advisory Body should note that these kinds of bodies should have a seat at the governance table. To be sure, in a UN context, states will make ultimate decisions. But non-state actors like these should be accredited participants in what should be genuinely multistakeholder governance forums, in which they may not only participate but chair the kinds of bodies (norm developing, enforcing, etc.) that might result. A purely state-driven enterprise, keeping in mind the kind of special access given to major corporate enterprises, would be inconsistent with the norms proposed here while also antithetical to the premise with which the Advisory Board began: the need to address concentrations of state and corporate power.

Authors