Community and Content Moderation in the Digital Public Hypersquare

Richard Reisman, Chris Riley / Jun 17, 2022Richard Reisman is a nonresident senior fellow at Lincoln Network; Chris Riley is senior fellow for internet governance at the R Street Institute.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

Current news is awash with acute concerns about social media content and how it is or is not moderated in the so-called “digital public square.” But at its core, the problem is not best understood through the lens of content and moderation, or through efforts to engineer public values and structures into for-profit social media platforms. Rather, it’s about the power to shape dialogue, and how that power is built, allocated, and used. Social media power fills a vacuum that is arising from the collapse of social structure and context in how people currently connect on the internet.

Managing that power responsibly requires recreating some digital equivalent to the kind of social structures and contexts that society developed over past generations. As a start on that, it is essential to understand that what is often framed as the “digital public square” is not really a single, discrete square, but is better seen as the “digital public hypersquare:” a hyperlinked environment made up of a multitude of digital spaces, much as the World Wide Web is a hyperlinked web made up of a multitude of websites.

Recognizing the multidimensionality and interconnected nature of these social squares (or spaces) can facilitate flexible, context-specific content modulation, as opposed to the blunter, less context-specific tool of moderation-as-removal. Instead of framing content policies as centralized, top-down policing– with all of that frame’s inherent associations with oppression, at one extreme, or anarchy, at the other– social media governance can be envisioned as a network of positive community-built, community-building layers, running in their own contextually appropriate ways, over the top of modern-day networks. This provides a new logic for diagnosing and beginning to treat how social media now exacerbate many of the disease symptoms that now present with increasing severity.

For example, former President Barack Obama gave a speech at Stanford University in April 2022 focusing on disinformation and democracy. Two quotes are particularly notable. First, he recognizes the loss of what he calls “communal glue” from social institutions:

Here at home, we’ve seen a steady decline in the number of people participating in unions, civic organizations and houses of worship, mediating institutions that once served as a kind of communal glue.

In addition to the loss of these shared spaces that act as equalizers and as physical infrastructures that facilitate connection with others, institutions that were once held in near-universal regard as authoritative sources of truth—-particularly newspapers and universities—have become increasingly questioned in the broader cultural and political wars of today.

The second quote from President Obama’s speech calls out the weaponization of this dynamic to further the breakdown of institutions and infrastructures of order and mutual trust:

People like Putin and Steve Bannon, for that matter, understand it’s not necessary for people to believe this information in order to weaken democratic institutions. You just have to flood a country’s public square with enough raw sewage.

Barreling into this complicated intersection of institutions, information, and the internet comes Elon Musk, the world’s richest person and an unpredictable and ungovernable character, with an unsolicited offer to purchase Twitter. Musk is explicit in his plans to scale back Twitter’s content moderation until the company’s speech policies mirror a culture warrior’s creative reading of the First Amendment. Without question, Musk’s attempted acquisition (which may yet collapse) was not a business-first proposition despite the typical profligate pitch deck. Rather, it is the opportunity, perhaps better framed as the power, to shape public discourse that most likely holds appeal for Musk. His focused interest highlights the deeper stakes in this battleground: how and by whom should this new power to shape public discourse be managed?

Social Media as Modern-day Digital Public Squares

Social media services are frequently described as modern-day “public squares,” including by the Supreme Court in a 2017 case. Twitter co-founder and long-time CEO Jack Dorsey repeatedly described Twitter as a “digital public square,” most notably in a Congressional hearing in 2018. For better or worse, Twitter has become the primary place online “where borderless elites engage in democratic discourse” according to Anamitra Deb of the Omidyar Network—even as it is simultaneously “the loudest megaphone in the attention economy.” This important First Amendment metaphor has also become central to the misguided and unconstitutional Texas law that would treat all large social media platforms as “a modern-day public square.”

Among others, law professor Mary Anne Franks has interrogated this metaphor of the public square in depth, and calls it “both misleading and misguided.” Her counterarguments dissect the difference between private and public spaces under American law, and make a number of both legal and normative arguments as to why speech online can and should be managed to a higher standard than Musk’s vision. She also covers the extensive historical exclusion and discrimination associated with the overly-idealized concept of a public square, both of which are dynamics that are very much on display with modern social media.

An equally significant limitation of the “digital public square” metaphor for social media is its singular nature. Global society does not have one public square, at least not since the heyday of the Roman Forum. To borrow from Silicon Valley’s lexicon, a single “public square” just does not scale.

Society has always had many “squares” (or “spaces” or “spheres”) for speech, discourse, and deliberation, with varying levels of openness and varying community standards. As Franks explains, it’s both more descriptive and normatively preferable to set aside the “unitary focus” of the public sphere theory, which she attributes to Habermas, in favor of philosopher Nancy Fraser’s call for “a plurality of competing publics.” As Franks explains:

In place of an idealized, unitary public square, we can envision the flourishing of multiple spaces—online and off, public and private—that provide the conditions necessary for free expression and democratic deliberation for different groups with different needs. This vision would entail crafting law and policy to ensure that no single host or forum, or even single medium, dominates the shaping of public opinion.

This need for a diversity of spaces becomes even more obvious with the scale that results from the internet’s network effects. In creating a “global village” of billions of people a unitary public sphere vision becomes unmanageable.

While the internet certainly makes public engagement easier, it currently falls short as a tool for realizing the positive benefits of dialogue and deliberation. A recent Gallup/Knight survey found that 90 percent of Americans believe social media facilitates the spread of “harmful and extreme viewpoints,” and 71 percent believe the internet is more divisive than unifying. Tom Glaisyer’s work on “The Digital Public Square” validates this conclusion and argues that mitigating the divisive dynamic isn’t a simple matter of transitioning to a new technological environment. Rather, the lack of institutional participation in the digital public spaces as currently constructed and operated causes those spaces to fail as an engine for promoting democracy:

In sum, this confluence of the economics of surveillance media and media structures and the incentives it has created, as well as the assertive independence of the news media, has resulted—arguably inadvertently—in a set of circumstances that privileges the production, distribution, and digestion of content in a manner that is testing norms of truth and fact that have sustained democratic culture within the United States.

A Hyperlinked Web of Many Digital Public Squares “Deeply Intertwingled”

Embracing and building on the idea that the public square is not a unitary, discrete concept may provide a new opening for making social media both less harmful and more valuable. A new metaphor that may help make sense of the struggle around the use of public squares is to think beyond the image of a single square, like the local, physical town square where people came together to interact. Instead, we should imagine a multi-dimensional hypersquare—a networked set of squares, each individual, yet all connectable as desired. This builds on Ted Nelson’s visionary and now-familiar design concepts of hypertext and hypermedia connected by hyperlinks (originally proposed in 1965), that brought the multi-dimensionality of the “World Wide Web" to previously discrete, linear media. He explained his objective as being to apply computers to support the rich structure of human creativity –“The Complex, The Changing and the Indeterminate,”–as he put it, to serve not technical, but psychological needs in a conceptually simple and powerful way–a way that can help people make sense of their own “multitudes.”

In the same way, a digital public hypersquare (or perhaps a hyperspace?) extends the metaphor of a public square into an open-ended network of spaces that can each be governed by different rules and norms. Some of these spaces could be run by individuals or businesses, and others by governments; some spaces could adopt broadly permissive expression standards, while others would mediate harmful and inappropriate (in local context) speech to create a safer environment. Some might have largely bottom-up control, perhaps organized as cooperatives, while others might be more top-down, as each finds the governance structure most suited to their mission and to the “market” of the audience that opts in to their services. Across all of these spaces, people can engage at will in the activities that we associate with the “public square.” They express views on politics and issues of the day, they assemble into groups that can engage in collective action, they sell goods and offer services, and they share information—both the true and false kinds.

Much like the World Wide Web and its interconnected universe of websites, all of these spaces conceptually exist within the same web-like structure, and are capable of being connected to each other in various ways. Data and populations of interacting individuals and communities can flow more or less freely from one space to another, sharing and receiving messages under the constraints appropriate to each local context, much as current websites have varying degrees of openness. The elements of this digital public hypersquare, and the ideas and entities they represent, are all “deeply intertwingled,” to use Nelson’s expressive phrase, which suggests the ability to both intertwine (preserving distinct forms) and intermingle (blending into new forms).

The notion of a hypersquare emphasizes the new features of our digital spaces that change how information comes to our attention. They are hyperlinked, with coded linkages that put other squares just a click away. They are also more easily soft-linked by their human users, who can cross-post from one space to another. That overlap and intersection of squares adds to the moderation challenge: for example, mass-shooting videos get cross-posted faster than they can be removed. Equally important is the issue of what speech is heard by whom, and when. The conversation within the single space of a platform is often presented selectively in a “news feed” of items that is individually composed and organized for each user.

This hyper-web-of-spaces model becomes even more relevant, as what are now distinct, siloed social media platforms move toward a more distributed, “federated” model that is fully interconnected. This might occur in a mixture of ways, including through the growth of a single platform, user delegation to third parties of functions that had been internal to the platforms, and/or by the growth of new federated services like Mastodon or (perhaps ironically) the success of Jack Dorsey’s recent ambition for Twitter, project Bluesky.

Importantly, this frame of a digital hypersquare (whether fully public or semi-private) is offered for both descriptive and normative purposes. The modern-day internet is increasingly “pan-media:” more than Facebook and websites, expressive activity and assembly also occur on Reddit, through YouTube videos and discussions, and in Discord chats. Extending this platform-level diversity to include a range of options for interfacing with each network and content—not merely a choice among networks, but a choice of interfaces within each network and across all networks—is a key part of our earlier delegation article. But, whether at the current platform diversity scale or ina more fully diversified intermediary future, the question that arises is: What does this interconnected structure of separate spaces mean for content moderation practices?

Moving from Content Moderation to Content Mediation is Not Enough

Operating with the faulty notion that the internet and social media comprise a singular digital public square makes modulating the balance between free expression and online safety a perpetually fraught exercise. The presumptive solution under this unitary public square model has been to set content policies for a system articulating impermissible behavior—often beginning by assuming that everything is allowed except that which is specifically forbidden—and then putting resources into enforcement to remove the inevitable violative content and behavior after it has been initiated.

But as Mike Masnick puts it in his self-anointed Masnick’s Impossibility Theorem, “content moderation at scale is impossible to do well.” Ironically, the same network effects that increase the value of additional users as systems grow also increase (at least linearly) the surface area and risk of content moderation, in contrast to otherwise decreasing per-user costs through economies of scale. Also, the setting of policies by a centralized network operator carries with it an unavoidable chill of top-down policing, a term that describes controls imposed by an institution at a time of deep skepticism of institutions and the motivations of those that direct them, and a corresponding breakdown of shared legitimacy and trust.

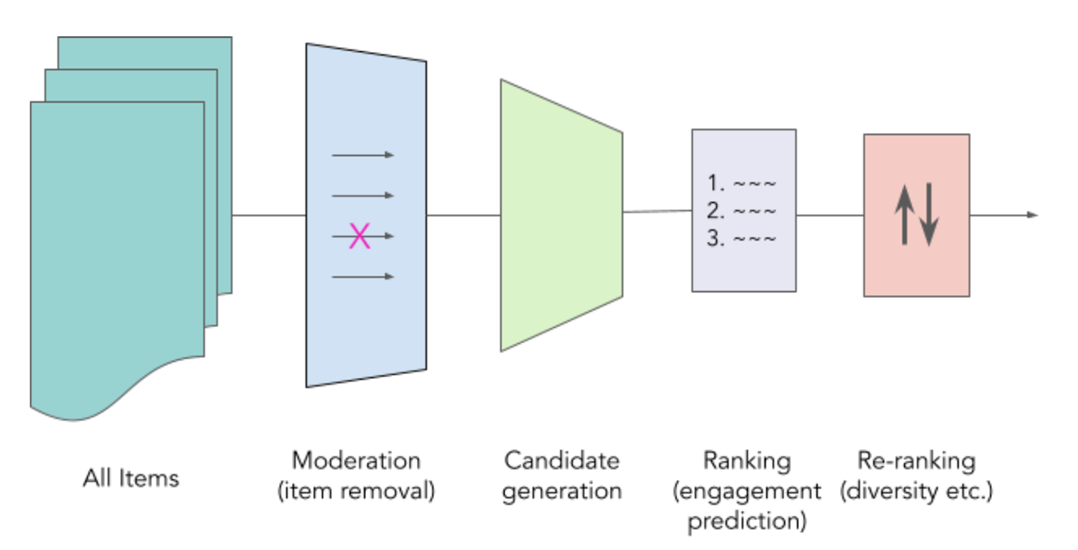

Fortunately, modern-day content management practices offer a far richer universe of remedies to mitigate harm than the false binary “take down, or not” narrative that often dominates. In fact, the very term content “moderation” is increasingly misleading, given that it is commonly understood to mean removing “bad” things instead of selecting good things. As attention shifts to the central role played by recommendation engines, a broader lens of content mediation across the arc of removal, selection, and prioritizing practices is more reflective of modern realities and user needs. Jonathan Stray diagrams ranking alongside moderation as follows:

Distrust and concern have grown despite huge efforts on content mediation as removal. Facebook and Twitter came in at 97th and 98th place, respectively, in a recent Axios-Harris poll of 100 company reputations. Part of the reason may be the continued feelings of loss of agency in this richer content mediation ecosystem, given the “black box” nature of recommender systems, it’s hard even for experts to explain their outputs, and for individuals concerned that their content is not being treated fairly, resolution in such a structure is difficult. The evidence of a problem is clear, but there is no clear theory or consensus on how to solve it. Lacking that, the European Union’s forthcoming Digital Services Act mandates transparency in social media and search engines along with accountability mechanisms including impact assessments and risk evaluation and mitigation.

Another reason for the continued lack of trust and the concern that democracy is being undermined may derive from social media’s poor support for what Nicklas Lundblad describes as one of two key parts of the value of free speech: “a mechanism for deliberation.” Lundblad’s other key value—social media as a mechanism for discovery—is realized in scope (if not discrimination), through modern centralized systems built around the fairly simplistic and context-free focus on individual pieces of content. But those same structures struggle to support the nuanced utility and value of speech for qualitative deliberation. To Lundblad, new mechanisms that realize this positive free speech vision are needed, mechanisms that push control toward the users at the edges, including the possibility of edge-controlled filtering–and user delegation of the ranking and recommendation layer of Stray’s model.

Masnick’s system-level analysis of the challenges of content moderation at scale, combined with Lundblad’s framing of free speech as grounded in deliberation and some of the nascent discussions around the free speech rights of listeners to choose what they hear (“freedom of impression”), together support the notion that any large system using a singular set of policies will always be overbroad and underinclusive for many individuals and communities, as values differ too widely. Centrally managed content mediation, like content moderation, is impossible to do well at scale—it is a nuanced task that is highly contextual, and thus requires a correspondingly nuanced structure of distributed processing and control to be done well. (This is not meant to denigrate the value of trust and safety work for mitigating harm and improving individual experiences online. Rather, the centralized structures in which this work currently takes place should be presumed to always impose impossibly increasing burdens for it to bear.)

Building the Connective Community Tissue of a Functional Digital Public Hypersquare

Humans learn from and influence other humans; this dynamic is integral to the reflexive nature of media. It has been studied through a substantial literature in philosophy and sociology. A classic work in sociology speaks of The Social Construction of Reality, and a more recent work, The Mediated Construction of Reality, incorporates social media into the theory of how humans understand the world. Similarly, in the philosophy of knowledge (epistemology) the theory of “Epistemic Dependence” contends that much of what humans know comes from other people rather than from our own firsthand experiences of the world. Coming from the hard sciences, Matthew Hutson’s work in the MIT Technology Review shows that complex research relies on “sophisticated technical and social systems” in a cycle where “[t]rust feeds evidence feeds trust.” He then extends this to the broader context of society and media:

The same holds true for society at large. If we undermine our self-reinforcing systems of evidence and trust, our ability to know anything and do anything will break down.

Rebuilding trust online requires a conscious reinvestment in mechanisms that can better support the social roles of individuals and communities/institutions to achieve not only effective discovery but deliberation, critical thinking and hypothesis testing. Looking at social media as a digital public hypersquare suggests the need to create support for positive community-building structures and processes. As such structures and processes are built in the digital realm, we can design for diversity and inclusion without surrendering to either anarchy or authoritarianism.

The “marketplace of ideas'' model of speech has appeal as a means of promoting diversity and inclusion in speech, but also has fallen into some disrepute relating to market failures. But this is not a simple marketplace–it long ago grew into a complex market infrastructure, based on a “marketplace of idea mediators” (for example, newspapers and the other kinds of mediating institutions whose decline Obama described) that individuals could choose among and apply in combination to guide their listening, discovery, and deliberation, mediators that in effect competed to serve their audiences.

The market selection of these curatorial mediation services was originally done manually by each individual, and some of the mediators, such as newsstands, libraries, and review services, offered some rudimentary approximation of a general news feed as a newsletter or bulletin. But now the digitization of everything has shifted the composing of our “feeds” into code. The code that does that mediation of what we each see in social media is now controlled unilaterally by social media platforms with little provision for user input or delegation, leaving little role for any marketplace of idea mediators. That is a fundamental concern to the building of truth in society, no matter how well-meaning and diligent platform policy teams might be.

In modern social media (as explored in our previous essay), humans are central to the core reflexive cycle of content production, engagement, and propagation. Engagement metrics are one of the oldest tools in the recommendation engine toolbox. Content that is popular is currently rewarded with prioritization in ranked feed presentations, because it is presumed to be more desirable than content that is less popular. But this simplistic metric of human judgment collapses context.

Looking at the interactions with content of humans in communities, rather than the undifferentiated aggregate of individual interactions, offers richer signals that can reach into the deeper values of speech beyond expression for its own sake – whereas undifferentiated popularity often favors the empty or sensationalist. Moving away from a narrow focus on superficial metrics of short-term engagement in ranking algorithms can restore the crucial role of human social intelligence, which cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence, but should be augmented by it.

We have some (still very limited and imperfect) hints of what more sophisticated structures for human mediation look like in digital forums that are designed to empower individuals. Wikipedia, for example, is a well-known example of an information ecosystem shaped by the intentional actions of editors working within a community with well-established norms and rules. Reddit, similarly, divides its “subreddit” spaces in a manner highly evocative of Fraser and Franks, allowing each to be largely managed by separate communities applying separate policies.

Efforts are already in the works to start layering these community-centric techniques onto broader platforms, particularly the World Wide Web, given its openness. Newsguard offers a plugin that rates individual websites on a scale of trustworthiness using standard metrics and professional journalists to make categorizations with a degree of objectivity and inherent legitimacy (at least, for those who still respect journalism). Public Editor pushes some of the same tools of criticism and misinformation correction into the hands of citizen journalists, carefully combined through tools intended to minimize bias and maximize credibility. However, such downstream tools are still largely limited to labeling rather than more active mediation.

Far richer innovations are possible. One idea with promise is an adaptation of the PageRank techniques that made Google’s search engine so effective. PageRank’s central innovation for search was to track and analyze links between web pages as indications of the judgment of humans (originally “webmasters”) in determining the “quality ranking” of individual web pages in the context of a search query. The Integrity Institute proposes a variant of this approach, recommending that Facebook compute quality scores for its Pages (the parallel of web sites) and incorporate these data points into recommendation engines whose output is individual pieces of ranked content. According to their analysis, such a change would drastically improve the assessment of meaningful engagement and quality content. Co-author Reisman has proposed such a PageRank-like strategy be extended to rank inputs from individual users based on their reputations (as signaled by other humans) in specific community and subject domain contexts.

But when the goal is building mechanisms that optimize for social truth-seeking and quality deliberation, even innovations like a social media version of PageRank will only scratch the surface, because the space for experimentation and learning is constrained within the silo of an individual company’s platform and A/B testing operations. This limiting of the digital public hypersquare into a set of disconnected and ultimately dissatisfying digital public squares greatly holds back the level of social learning and deliberation that is possible.

The alternatives are part of public discourse now, suggesting ways to reimagine the digital public hypersquare and processes of content mediation operating on it, and the benefits of such approaches for democracy, restoring the role of human control within the human-machine loop. The Tech Policy Press mini-conference on Reconciling Social Media and Democracy featured many of these perspectives in its opening discussion, such as the Stanford middleware proposal. Twitter’s offshoot Bluesky project is teeing up a compatible architectural landscape, “separating speech and reach” to create more freedom at the moderation stage. And these are only some of the most recent examples, with earlier proposals including Stephen Wolfram’s “final ranking providers” from 2019 Senate testimony and Masnick’s “protocols not platforms” thinking, first published in 2015. These and other similar proposals were surveyed and discussed in some depth by co-author Reisman, as were possible solutions to implementation concerns.

Collectively these ideas buck against the integrated silos of today in favor of separation of the basic indexing and storage layers from a higher layer of diverse culture- and community-centric spaces that operate more context-specific content mediation and presentation systems. They provide examples of infrastructure changes that would give users the power to delegate ranking/recommender functionality to services that work as their chosen mediation agents to help compose their feeds.

But that is just the foundation technology for revitalizing the mediation ecosystem with a rich web of community and institutional spaces. The next level of that vision is in the human organizational process of building out this web of communities and institutions—both new kinds of mediators and revitalized updates of existing ones—and in clarifying what added functionality might be needed to fully support their operations and enrich the discovery and deliberation services of this newly digitized mediating ecosystem layer. As Franks concluded:

If we move beyond the public square, we can imagine a multitude of spaces designed for reflection instead of performativity; accessibility instead of exclusion; and intellectual curiosity, humility, and empathy instead of ignorance, arrogance, and cruelty. We can imagine spaces designed for democracy.

Mediating Our Multitudes So Humanity and Democracy Can Thrive

As Walt Whitman observed, we contradict ourselves because we contain multitudes. Some fear the multitudes we contain, and seek certainty in a neat, binary reality. But human society has thrived and progressed by managing the uncertain but generative dialectic of its multitudes with a light hand.

Elon Musk’s attempted acquisition of Twitter has spotlighted concern over the state of free speech and public engagement online, and ultimately helped illustrate how poorly we are dealing with the fragility and limitations of modern digital platforms as foundations for democracy. As social media platforms have grown from small communities with human moderators to global complexes managed by huge commercial platforms, they have outgrown the notion of a unitary digital public square that can be centrally managed by principal reliance on moderation-as-removal. Yet that frame unfortunately still dominates much of the discussion.

The best path forward is to recognize and reinforce the critical role of interconnection within the hypersquare of digital public spaces, and build into that information ecosystem an open and evolving infrastructure of tools and services for community empowerment and deliberation. That can bring new power to the generative processes of social intelligence and adaptive cooperation that fueled the progress and survival of healthy societies in an ever-changing world. Further articles in this series are planned to explore that path in more detail.

- - -

This is the third in a continuing series of related essays by Reisman and Riley in Tech Policy Press:

Authors