The Rise and Fall of Nvidia’s Geopolitical Strategy

Leevi Saari / Oct 8, 2025

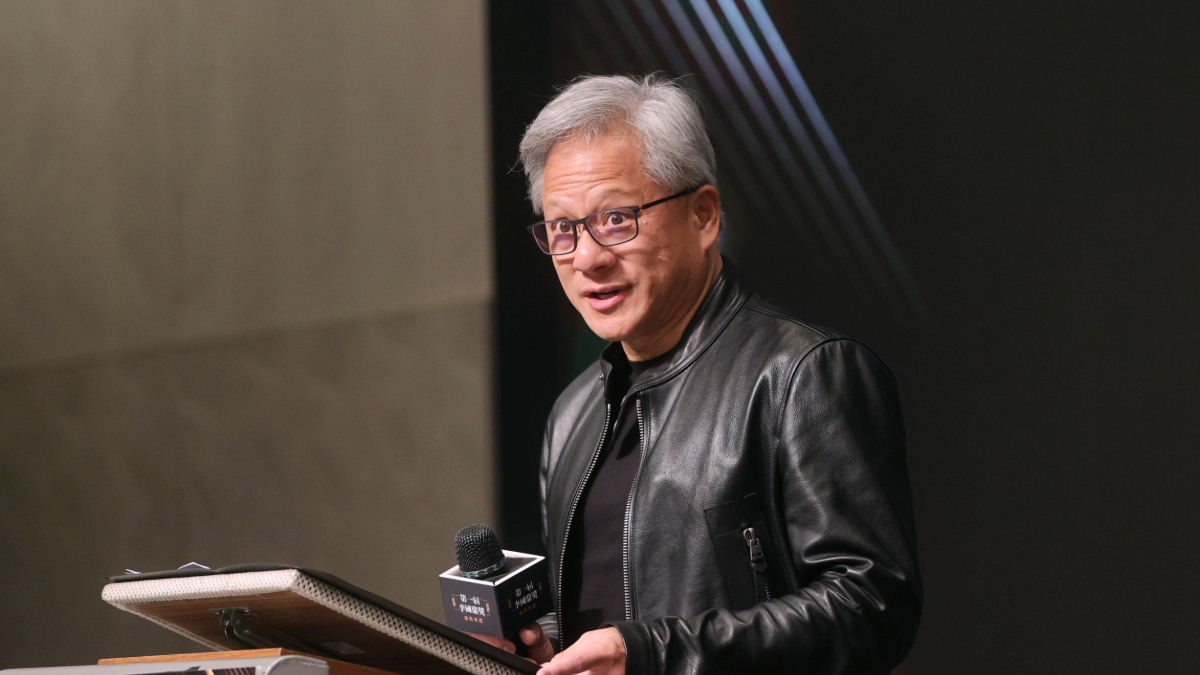

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang at the K.T. Li Awards 2023 in Taiwan. (Taiwan Presidential Office)

China’s Cyberspace Administration last month banned companies from purchasing Nvidia’s H20 chips, much to the chagrin of its CEO Jensen Huang. This followed a train wreck of events that unfolded over the summer.

After an arduous lobbying campaign over the summer that included a bilateral meeting with United States President Donald Trump and Huang in early July, Nvidia in August was finally able to secure licenses from the United States to export the throttled-down chips to China, unleashing a lucrative backlog held up by geopolitics.

But US officials had already doomed the arrangement by antagonizing the Chinese during the lead-up to the deal.

First, by threatening surveillance. Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle in May introduced legislation to include mandatory location tracking capabilities and potential remote kill switches with exported chips. Chinese authorities summoned Nvidia representatives to explain. Nvidia tried to allay the Chinese suspicions that such backdoors would exist in their chips and signaled to the US government the desire not to be weaponized for geopolitical purposes.

Second, by humiliating the Chinese. US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, perhaps to appease the more hawkish parts of Trump’s constituency, told CNBC in July that the chips now allowed to be exported to China were “not the first, second or third grade” chips, but a part of cunning “strategy of addicting the Chinese” to fourth-rate United States tech. Chinese officials, it turns out, read US newspapers and found those comments “insulting,” with implicit undertones to the Opium Wars of the 1800s, when Britain forced China to legalize the drug, leading to a spike in addiction.

These tensions evolved during the summer. In response to the developments, Nvidia sought to distance itself from the geopolitical tensions. In an instructive quote showing the delicate tensions the company tried to navigate, a Nvidia spokesperson noted that “[a]s both governments recognize, the H20 is not a military product or for government infrastructure. China won’t rely on American chips for government operations, just like the US government would not rely on chips from China. However, allowing US chips for beneficial commercial use is good for everyone.”

Well, at least for Nvidia.

China’s Cyberspace Administration finally had seen enough, however, and on September 17 banned the purchase of H20s for the country’s companies. Jensen, visiting the United Kingdom in Trump's entourage at the time, argued, “We can only be in service of a market if a country wants us to be … I'm disappointed with what I see, but they have larger agendas to work out between China and the United States. And I'm patient about it.”

This episode, far from being a series of isolated incidents, signals a broader breakdown of a corporate strategy designed to navigate complex geostrategic tensions.

The one equation to rule them all

From a national security perspective, the export of advanced semiconductor chips to China is often discouraged. If AI is a strategic technology that affects the relative power of states in geopolitical competition, and if the sought-after GPUs are a scarce input to that technology under the control of US-headquartered corporate entities, then exporting them amounts to an act of self-sabotage in global geopolitics. Granted, sometimes the adversary might have similar strategic assets that might justify the exchange in a spirit of necessity. In general, however, chips are reserved for domestic consumption in the pursuit of geopolitical power.

This is an unfortunate perspective for Nvidia and its shareholders. China is a large export market for chips, and the potential for profit in that expanding market is considered by the company to be a 50 billion dollar opportunity. Hence why Nvidia, led by Huang, has been pushing an argument to redefine the geo-strategic interests of the United States in a way that aligns with the company’s own commercial interests. This has led to formulation of a geopolitical concept that I would dub the Nvidia master equation.

The intuition behind the concept is simple. If Nvidia does not export its chips, Chinese AI companies will be forced to look for alternatives, which incentivizes more research and development by Chinese actors, intensifying competition and ultimately the development of a comparable Chinese chip. That is why, according to Nvidia, maintaining Nvidia’s quasi-monopoly in chip design is a matter of geostrategic national priority and argument for the export chip. It is a brilliant strategy of combining corporate and state interest — if one can pull it off. And Nvidia has recently been successful in pushing this to the highest levels of policymaking.

Breaking down this logic to its component parts helps to see how it works with more clarity.

Basically, the idea is that Chinese companies will shift away from Nvidia when the gap between the capability of Nvidia chips and Chinese chips (e.g., Cambricon, Huawei) and the work needed to transition from Nvidia to a local alternative is less than the perceived risk of their dependency.

According to this logic and keeping other factors constant, letting Nvidia sell chips to China is the key factor in maintaining the capacity gap high enough to prevent companies from switching to alternatives. That is, there is an elusive threshold, a point at which Chinese AI companies deem that the increased capability they get from using Nvidia chips instead of local chips is not worth the political pressure urging them to develop domestic alternatives that could spur eventual switching. Maintaining the capacity gap by adjusting the export limitations becomes a crucial lever for policymakers.

This threshold likely rises over time. An increase in Chinese capacities creates pressure to increase the capacity thresholds of the licensed chips to maintain Nvidia's market share, while calls to throttle Chinese AI capacities by not giving access to the leading chips push the capacity thresholds downward.

This balancing act is the backdrop against which we have to understand the cat-and-mouse game of the US export control strategy constantly adjusting capacity thresholds, to which Nvidia responds by designing a chip that just barely skims the legal boundaries as a middle finger to the administrative state. This is the story of the Nvidia’s H800 and H20, as has been chronicled elsewhere.

Whether this back and forth can last forever is up for discussion. One potential underlying logic reflects the strategies that digital platforms undertook in previous digital waves. Nvidia is betting that by keeping competitors at bay for a sufficient amount of time, the ecosystem’s development of alternatives will gradually become more difficult as capital sources and a customer base enabling a short innovation loop will dry up. This would smother the nascent Chinese ecosystem and ensure that the US still maintains a structural lever over Chinese development. This is a bold bet that might underestimate the Chinese resolve not to stand as a subservient part of the US-dominated global technological order. Barring some hard limits in the Chinese capacity, it is hard to see how this strategy would be stable over the long term.

Another important consideration is the costs of transitioning from one chip to another. GPU hardware is not a bulk product. Rather, the code is written for particular chips in particular programming languages, which creates a strong software-hardware bind that locks in customers. This is where the core source of Nvidia’s market power lies. Its proprietary programming language ecosystem, CUDA, is the workhorse for modern AI development. It is often a challenging task to rewrite one’s full code base from CUDA to another language. This “CUDA moat” has often been cited as the core competitive advantage of Nvidia, although alternatives such as AMD’s ROCm are starting to emerge as serious alternatives in the Western world.

This transition cost from CUDA to other frameworks (like Huawei’s CANN) is still formidable. It is precisely for this reason that the markets are hyped up by the smallest of signals that the transition costs would be lowered and hence the dynamics in this ecosystem. Cue the news from DeepSeek in August, which suggested that DeepSeek had started to make its models compatible with domestic chip suppliers. While the original information was apparently based on a comment on a Weibo social media post announcing a new launch, this signal caused a frenzy in the stock market pushing up the stock value of local startups.

In a world without geopolitics, the story would end here. The decision to switch would be based on business logic alone, happening only when the Chinese chip is sufficiently better than Nvidia's that the capability benefit outweighs the cost of transition. This means that Chinese chipmakers would need to provide a chip that is "better" by an amount exactly equal to the trouble of changing from solutions tailored to the specifics of an Nvidia chip to a domestic alternative, say, from Huawei.

Politics strikes back

But this is not the world we live in. The kicker is politics. It matters how dangerous China perceives the use of Nvidia chips to be and whether it will continue to allow Chinese companies to use them.

If the two sides of the equation were independent of each other, we would be talking about business strategy. Nvidia’s Huang appeared to want a strategic, nuanced backroom business deal where, through smart and deliberate maneuvering, he would be able to manage his competitive environment — a strategy in which he has shown masterful skill, navigating Nvidia’s ecosystem of partners, suppliers, buyers and competitors in the highly complex and layered environment of the haute business of the 2020s.

But what he might not have not counted on is the fact that his strategy of maintaining the capability gap had to be circulated through the structures and quirks of politics.

In a heated geopolitical environment, his strategy of maintaining the capability edge just enough to starve out the Chinese ecosystem was too fine-grained for the more pugilistic impulses of contemporary US foreign policy vis-a-vis China. To mediate domestic political backlash from policy constituencies accusing the sacrifice of US national interest on the altar of profit-making, the executive branch needed to explain itself by highlighting the faults of the chips and a strategy to weaponize these chips in the future by including methods of remote control and observation.

In doing so, they made the rest of the equation unsustainable. In a show of either severely overestimating the capability gap or underestimating the resolve of the Chinese state, outlining the logic in plain sight pushed the dependency risk up significantly, with the added feeling of humiliation that finally tipped the balance.

And that is where we ended up three weeks ago, when the Chinese authorities told the largest Chinese tech companies to stop their planned orders of Nvidia chips, breaking down the equation, at least for the time being. Nvidia’s stock dipped 3%, which for a company the size of Nvidia adds up to a painful nominal value of $120 billion, in addition to lost opportunities adding up to billions in lost revenue.

Fine equations turned out to be too artisanal for the rough and tumble of Washington policymaking.

Authors