The ILO Debate on Algorithmic Management Will Define Worker Rights in the Digital Economy

Shikha Silliman Bhattacharjee, Nandita Shivakumar / Sep 3, 2025Shikha Silliman Bhattacharjee is head of research, policy, and innovation at Equidem. Nandita Shivakumar is a communications consultant who collaborates with Equidem.

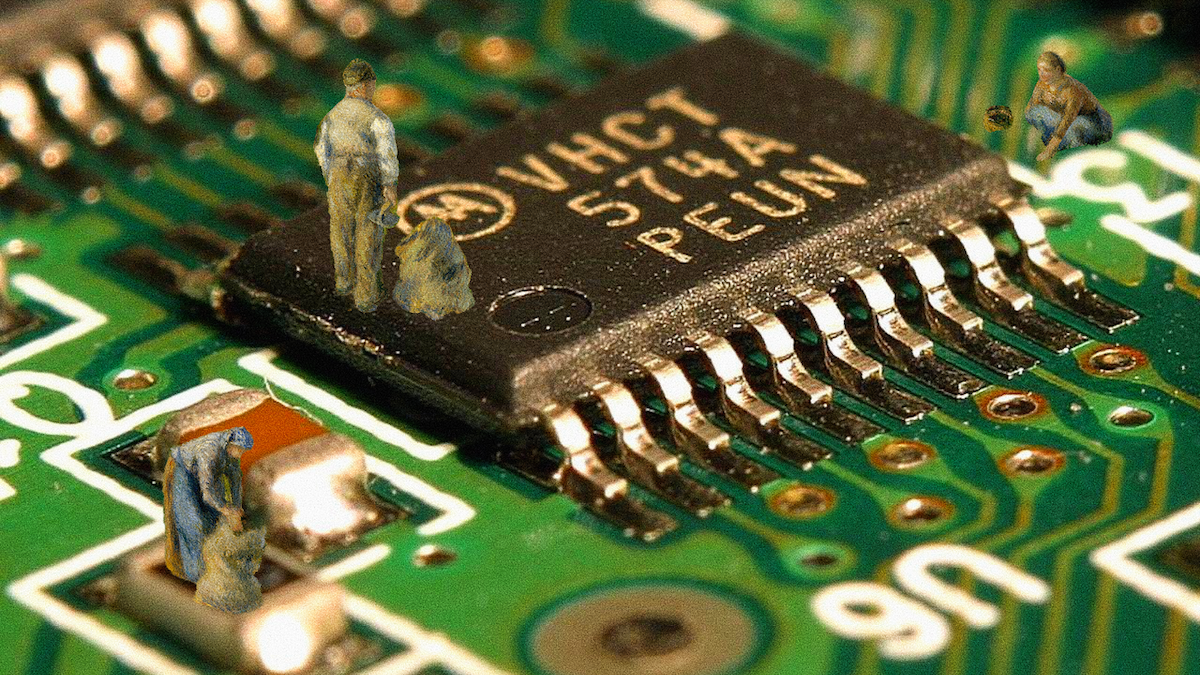

Elise Racine, Occupational Circularity, CC-BY 4.0

Debates over algorithmic governance are increasingly defining the terms of work in the digital and platform economy. At stake is whether millions of workers will be recognized as rights-bearing employees, or treated as faceless “users” of commercial services, with no claim to fair wages, limits on working time, or protection against arbitrary dismissal.

The core legal question is deceptively simple: when an algorithm assigns tasks, sets pay rates, or deactivates accounts, is it exercising labor management or merely facilitating a commercial transaction? The answer will shape the global future of work.

This ambiguity came sharply into focus at the 113th International Labour Conference (ILC) in Geneva in June 2025, when "decent work in the platform economy" was formally debated for the first time. The United States, China, and the Employers’ group argued that regulating algorithmic systems amounted to a ‘mission creep’ beyond the ILO’s mandate, intruding into commercial and competition law. By contrast, the European Union, the Workers’ group, and governments such as Chile insisted that algorithmic governance is inseparable from labor regulation, as it directly determines pay, hours, and conditions of work.

Why this fight exists

To understand why this ILO debate has become so contentious and why its implications extend beyond Geneva, it is important to consider that algorithmic governance cuts across different legal domains.

Labor law, the ILO’s traditional mandate, regulates the conditions of employment, including wages, hours, occupational health and safety, and the right to organize. Competition law, in contrast, focuses on market dominance, pricing, and antitrust enforcement. Trade and commercial law govern the contracts and transactions that underpin global commerce, from cross-border e-commerce to service provision.

Algorithmic management operates at the intersection of these domains. Platform dashboards and scoring systems both structure commercial markets and control human labor. They decide not only which courier or driver receives an order, but also which business gains access to customers and at what price. In this sense, they function simultaneously as market allocators and workplace supervisors.

This dual character helps explain why employers and some governments have opposed treating algorithmic governance as a matter of labor regulation. At the International Labor Conference in June 2025, they argued that such regulation risks encroaching on domains usually overseen by commercial and competition law authorities. They warned that obligations written into a Convention on algorithmic management could clash with national civil and commercial codes, burden small and medium enterprises, and even resemble trade or antitrust regulation.

Workers’ representatives and supportive governments responded that these concerns were overstated. They stressed that a Convention would not interfere with genuine commercial transactions but would only apply where platform arrangements concealed an actual employment relationship or placed workers in conditions of economic dependency so significant that, in practice, it was equivalent to employment. In their view, algorithmic management cannot be regarded as a neutral market instrument, because in practice it influences wages, working time, and disciplinary measures, areas traditionally governed by labor law.

The costs of denial: Why treating algorithmic management as a 'commercial matter' harms workers

Treating algorithmic systems as ‘commercial tools’ rather than as mechanisms of labor management is not a technical distinction but a policy choice with direct implications for platform workers. We see three key harms that arise from this approach.

First, it allows companies to evade accountability for core employment responsibilities. If algorithmic control is treated as a ‘commercial matter,’ disputes that should fall under labor law can be recast as private contractual issues. In a conventional workplace, when a supervisor directs tasks and evaluates performance, it is recognized as management and subject to labor protections. Workers can demand fair pay, safe conditions, and due process. But when an algorithm exercises the same control, companies claim it is not management at all, but merely a feature of digital service design rather than management.

The consequences are stark. Pay withheld due to an algorithm’s miscalculation can be dismissed as a technical error rather than a wage violation. Deactivation of a worker’s account can be presented as a form of contract termination, not unfair dismissal. As documented in Equidem’s 2025 report, "Realising Decent Work in the Platform Economy," this approach leaves many delivery workers and data annotators — often subcontracted through multiple layers — without guarantees of wages, safety protections, or union representation. Violations that would ordinarily be monitored by labor inspectors or addressed in labor courts risk being pushed into the fine print of service agreements, which workers, especially in the Global South, have little power to contest.

Second, denying algorithmic management as labor management reinforces opacity as a business model. Digital labor platforms and AI firms often operate through complex contracting chains, nondisclosure agreements, and fragmented responsibilities, as documented in multiple studies. Algorithmic systems add another layer, enabling the allocation of micro-tasks within seconds, the constant ranking of workers, the imposition of penalties, and even blocking workers from accessing the app — often with little or no explanation. By classifying these mechanisms as operational features rather than part of labor management, companies can more readily avoid demands for transparency, accountability, or collective bargaining.

Workers also often lack information about how an algorithmic system operates — what metrics it uses, how scores are calculated, or why their accounts are flagged. When they ask, they are often told: “It’s proprietary, technical, and we can’t disclose the formula.” Without visibility into the rules, workers cannot prove unfair treatment.

Consider the case of a content moderator in Nairobi whose quality score drops overnight after a system update. Her pay rate is slashed, and she is threatened with termination. When she contacts support, she is told the algorithm flagged ‘repeated errors’ and the decision is final. In a conventional workplace, such disciplinary action would likely trigger grievance procedures, union intervention, or labor inspection. When algorithmic management is framed as a commercial issue, however, it is treated as an automated process beyond challenge.

This opacity is not incidental – it is structural to the business model, and companies will continue to defend it because it is profitable. The less workers know, the fewer questions can be asked about pay scales, workloads, or rights to freedom of association. Workers are then reduced to ‘data points’ in systems that can cut pay or end contracts without notice, severance, or due process, stripping them of the ability to contest decisions that determine their livelihoods.

Thirdly, it sidelines the ILO itself from shaping labor protections for digital workers. The ILO is one of the only global institutions where workers, governments, and employers sit together to set binding standards. Excluding algorithmic management from its scope denies data labellers, content moderators, and other AI supply chain workers this forum. Instead, rules about how algorithms assign tasks, set pay, or deactivate accounts are left to corporate policy and technical design, spaces dominated by companies, not workers.

The consequences are already visible. Equidem’s "Scroll. Click. Suffer" report describes digital workers facing constant exposure to harmful content without mental health support; arbitrary pay deductions linked to opaque scoring; sudden firings without notice; and physical harms such as eye strain, headaches, and insomnia from relentless screen time. If algorithmic management is treated as a commercial issue, these abuses remain outside the reach of labor standards. A Kenyan moderator developing PTSD after ten-hour shifts, or a Filipino annotator losing income overnight due to an unexplained downgrade, will not be seen as facing labor rights violations. Instead, such cases will be reduced to ‘technical glitches’ or private contract disputes, stalling the broader push for labor law to address them.

From recognition to regulation

It is important to note that efforts to regulate algorithmic management already exist, though they have been narrowly drawn. In the EU, for example, the new Platform Work Directive focuses mainly on civil and political rights, including transparency for consumers, data protection for individuals, and limits on intrusive monitoring of workers. These are necessary protections, but they do not address the rights of the people who power these systems. The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) also aims to address fair working conditions, yet it does not directly regulate algorithmic management, and its implementation remains uncertain. The gap leaves untouched the core social and economic issues of wages, working hours, occupational health and safety, and the right to organize for these platform workers — precisely the conditions that determine whether digital work is decent or degrading.

This is why algorithmic management must be recognized for what it is: a form of labor management. The dashboards and scoring systems that allocate tasks, set pay, and discipline workers are not neutral technical features; they are instruments of worker control. To deny this is to leave millions of workers outside of labor law protections at a time when such protections are most needed.

This is a critical juncture. The ILO is now debating how to govern platform work, and the precedent it sets will shape digital labor regulation far beyond Geneva. What the ILO decides will be relevant globally, as governments often look to it for guidance on labor standards. If algorithmic management is allowed to slip into a commercial-law silo, it will be almost impossible to reverse. The immediate effect would be to leave AI’s hidden workforce unprotected. The longer-term danger is even more serious: logistics firms, care platforms, and other industries that are already experimenting with algorithmic control will claim the same exemption. Missing this moment would significantly constrain the future governance of work.

To avoid that future, unions, civil society, and governments must advocate not only for recognition but also for clear technical safeguards. Three measures are especially urgent:

- Transparency requirements designed for workers, not just consumers. Platforms should be obligated to disclose to workers the metrics, thresholds, and decision-making processes that determine task allocation, pay rates, and deactivation — in plain, accessible language and local languages, not buried in technical or contractual jargon.

- Worker-centred impact assessments. Just as companies are required to conduct due diligence on the impact of their products on privacy, they should be required to carry out algorithmic impact assessments focused on wages, working hours, health and safety, and freedom of association. These assessments must be developed with trade unions and worker organizations, not only IT specialists, lawyers, or compliance officers.

- Due process and contestability. Algorithms should never have the final say on discipline or dismissal of a worker. Workers must have the right to challenge automated decisions, access human review, and seek remedy through labor law channels — not just customer service tickets or opaque appeals.

These proposals build on lessons already visible in practice. As Equidem’s "Realising Decent Work in the Platform Economy" report makes clear, without enforceable obligations for transparency and due process, opacity will remain the business model and labor exploitation its inevitable outcome.

The choice before us is stark. Either the ILO affirms that algorithmic management is management, bringing it squarely within the scope of international labour standards, or it allows a new frontier of unregulated work to take root. For the hidden workforce powering AI and for millions more who algorithms will soon manage, the consequences could not be more profound.

Authors