Learnings from Five Cases of Data Center Development and Defiance

Hanna Barakat / Jun 30, 2025

Aerial view of a data center owned by Google in Santiago on October 9, 2024. (Photo by RODRIGO ARANGUA/AFP via Getty Images)

The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence is driving a global surge in data center development. There are already over 1,000 hyperscale data centers globally, and estimates indicate that this number could at least double within the next five years.

These giant cement boxes, positioned as vital internet infrastructure, are often framed as opportunities for economic growth, deemed essential for national security, and pitched as global development projects with limited evidence supporting any real benefits for the communities often forced to host them.

Frontline communities, investigative reporters, and activists underscore the harmful impact of data centers, namely, toxic emissions, substantial water, energy, and fossil fuel consumption, disproportionately in areas experiencing drought and energy shortages.

Despite this emerging evidence, there remains a lack of information about (1) how tech companies and governments shape data center development; (2) the strategies local communities use to resist data centers’ harmful impacts, and (3) the desired resources activists, advocates, and researchers need to strengthen advocacy.

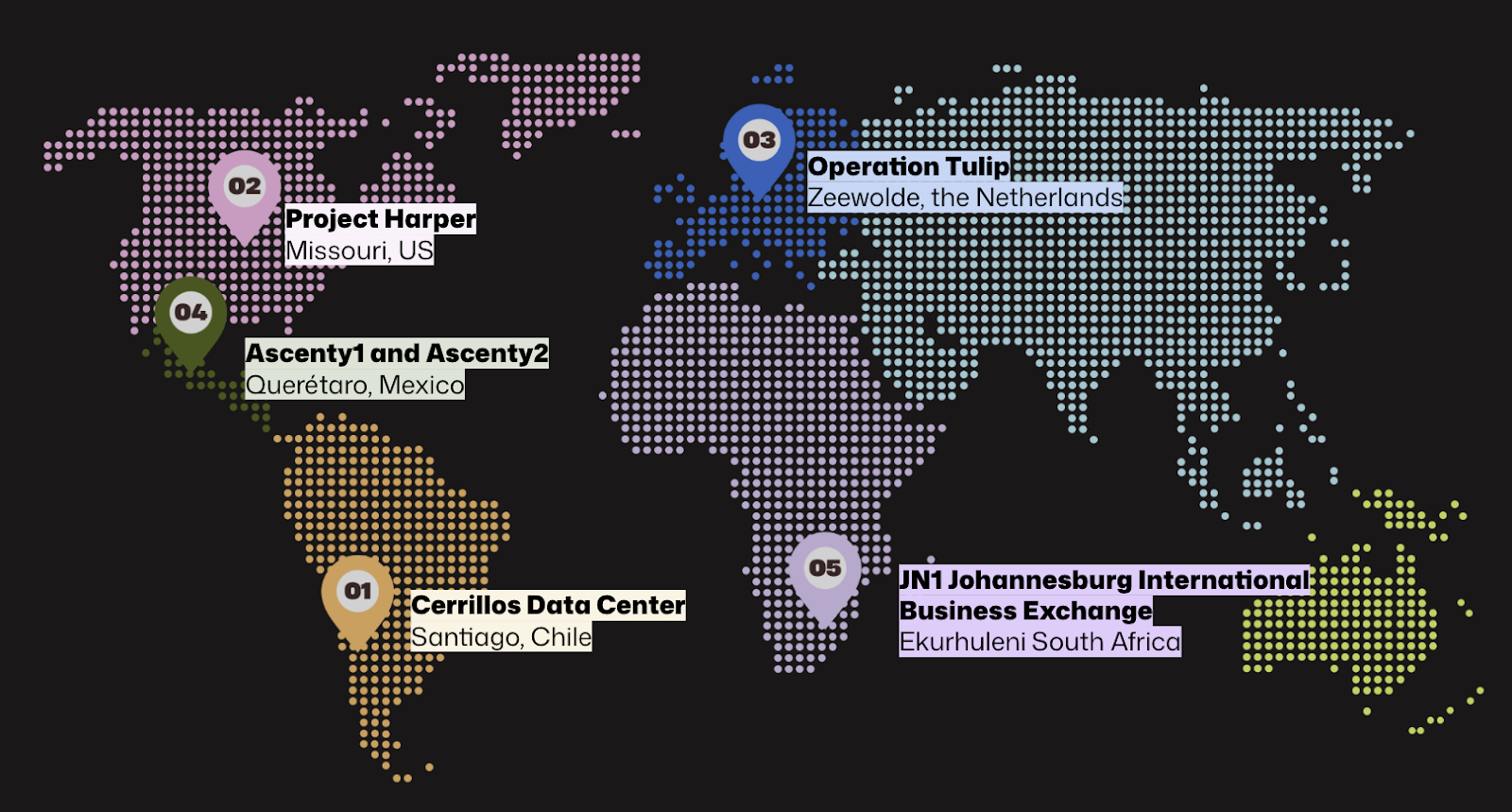

A team of researchers at The Maybe conducted a case study analysis of five data center developments in Chile, the US, the Netherlands, Mexico, and South Africa.

Through interviews and secondary analysis, our research revealed three key patterns:

1. Companies and governments are driving the narratives behind data center development.

Climate activists, researchers, and communities have documented company greenwashing tactics promoting data center development. The pitch is almost always “this will bring jobs and innovation.” One example is the creation of jobs in rural areas (eg, promising upward of 400 in Zeewolde and 100 in Querétaro). In reality, data centers employ at most 20 onsite jobs per center.

Additionally, The Wall Street Journal recently debunked inflated claims of data center jobs at OpenAI. Beyond job creation, companies often play up their sustainability metrics and increasingly promote the narrative that AI will help solve climate change. In a few case studies, the narratives about environmental considerations were inaccurate and so extensive that we presume they were intentional.

Media coverage of data center opposition is also sparse and often uncritical. Most countries have data center associations that support tech companies, acting as PR firms to improve their data centers’ image and release information about building progress.

Beyond greenwashing, data centers are proxies for geopolitical power dynamics and national agendas. Data centers are often strategically pitched as financial favors to small (often rural) communities. For instance, in Missouri, the town’s resistance to Project Harper was reprimanded by local officials for damaging their “ability to attract good, positive developments in the immediate future,” aligning with broader nationalistic rhetoric, in which supporting the data centers are positioned as a patriotic duty to further economic dominance.

Similar nationalist narratives can be seen in Equinix's rhetoric in South Africa, which sought to help “women and the youth” by “connecting Africa to the World.” Rhetoric supporting data center construction echoes ongoing narratives of promised ‘development’ that routinely accompany extraction from the local community. In this vein, carbon colonialism, where the Global North ‘outsources’ carbon emissions by moving its digital emissions to the Global Majority, is also apparent in the cases of Chile, Mexico, and South Africa.

2. Data center development is happening quickly and through opaque processes.

Data center development moves quickly, with opaque bidding processes and no centralized rules or standards for evaluating projects’ environmental impacts. For instance, in Cerillos, Google was evasive when environmental bodies asked whether the water rights they purchased were already in use. In Mexico, companies like Microsoft acquire water concessions without disclosing their identity in official records; procure utilities through intermediaries that do not update annual usage data; or operate within industrial parks, making it challenging to disaggregate water consumption by individual firms.

Even the sheer fact that a data center is in a proposed planning stage is often kept under wraps. Data center companies often require local governments to sign NDAs, as seen in the case of Cerrillos Data Center and Project Harper in Missouri, and/or use subsidiary company names to obscure their involvement in land acquisitions and government negotiations, as seen in Meta’s Operation Tulip in the Netherlands where Meta hid behind the shell company “Polar Networks” to avoid suspicion.

3. In the absence of critical reporting and publicly available information, communities are left to gather data independently.

Fact-finding is often undertaken by local advocacy groups, investigative journalists, and volunteer community members. For instance, in Chile, MOSACAT activists navigated technical documents to compile questions for Google. In the Netherlands, investigative journalists helped expose Meta’s greenwashing claims. In Mexico, Voceras de la Madre Tierra petitioned and wrote letters to the national courts. More commonly, investigations are ad hoc – taken on by a few dedicated individuals volunteering their time, as seen in Peculiar, Missouri, and in South Africa, where researcher Samantha Ndiwalana’s requests for information were repeatedly ignored by water and electricity utility companies.

One strategy for “successfully” halting data center development resulted from communities applying pressure to the ‘middle-men,’ such as utility companies, and local government officials. For instance, after consistent pressure, the mayor of Cerrillos, Chile, shared regret for not having warned his community of the environmental impact. Similarly, in Missouri US, the alderman expressed regret about a lack of transparency around signing the NDA. In Zeewolde, Netherlands, the residents' distrust of their current government was an incentive for a new, anti-data center political party to gain popularity.

This ‘physicality’ is an opportunity for coordinated action.

Data centers are a physical manifestation of where “the cloud” meets cement. But these giant cement boxes house more than just data; they are symbols of intersecting harms throughout the Global Majority, including the exorbitant use of limited local water and power, as well as the broader extractive global supply chain of technological development, and the growing accumulation of data used for surveillance and exploitation.

However, the site-fight nature of data centers results in siloed action and information. To address these structural challenges, we propose broad recommendations for philanthropic organizations, journalists, researchers, and other stakeholders.

- Providing material support to communities resisting data center development. This should include resourcing strategic litigation and investing in research and investigative journalism. For instance, in Chile, MOSACAT hired an environmental lawyer to represent them with Google and the various government agencies. In the Netherlands, the Zeewolde community relied upon expertise from energy researchers, which debunked Meta’s claims of a sustainable residual heat model. Sustained funding for independent research, investigative journalism, and strategic litigation is critical to addressing transparency gaps in the data center industry.

- Transparency & community consultation. Local governments and communities need better access to information so they can more effectively recognize and challenge corporate greenwashing. However, access to such information is often restricted. Thus, comprehensive frameworks could improve transparency around the operations of data centers. For example, the EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive will require stricter public reporting from data centers, in all EU countries on energy consumption, water use, and carbon emissions. While not yet in force, this provides an example of how data centers can be monitored, putting the onus on the companies to produce the data and on the government to enforce the framework, thereby establishing distinct roles for the public and private sectors. Additionally, while democratic consultation with community members is essential, public hearings and community consultation often happen after developments are secured or underway, if at all. As companies and developers are now strategizing ways to preemptively curb community resistance (in line with broader patterns of ‘greenwashing’ and ‘participatory-washing’), companies engaged in community consultation should be co-created in collaboration with organizers.

- Increasing multistakeholder and cross-movement convening. The rural nature of data center developments is crucial context when strategizing about convening. There is an opportunity for future cross-geographic and cross-movement learnings that address the lifecycle of harm across technological development. One example is the working group of local organizations (Ecologistas en Acción and Tu Nube Seca Mi Río,) that are collectively suing AWS. Supporting partnerships with energy researchers, environmental scientists, and investigative journalists to critically assess corporate sustainability claims would provide communities with credible counterarguments.

You can read more about the findings and recommendations in the report and contact The Maybe if you are interested in learning more about the growing ecosystem of actors focused on data center development and resistance.

Authors