Data Center Boom Risks Health of Already Vulnerable Communities

Cecilia Marrinan / Jun 12, 2025Cecilia Marrinan is the Tech Policy Associate at the Kapor Foundation.

Aerial view of data centers being built in Leesburg, VA. Credit: Gerville/2024

With the growing energy demands required for continued advancements in generative artificial intelligence (AI), the data center industry and Big Tech firms have ramped up investments and plans to quickly construct the necessary infrastructure and facilities to accommodate deeper AI integration across all sectors of the economy and society. This surge has raised substantial questions about the adverse impacts of data centers on the environment and public health, as researchers, activists, and policymakers grapple with the industry’s lack of transparency and strategies to mitigate significant impacts on host communities.

In light of concerns such as environmental degradation, high water usage, and increased energy demands, the data center industry has touted the benefits to communities hosting centers, including job opportunities, infrastructure development, and investments in regional sustainability, all of which are now being called into question. However, industry narratives consistently neglect a crucial element: location. To truly explore the impacts of data center expansion – both traditional and “sustainable” – we must examine existing and planned data center locations in tandem with cumulative historical and societal contexts.

As a continuation of the Kapor Foundation’s priority to advance equitable tech policy in California – specifically equitable technology infrastructure – this analysis aims to build awareness of the environmental and health risks that generative AI’s energy expansion poses to marginalized communities, and potential policies to address them. While linking specific public health outcomes to environmental factors or specific industrial activities is complex, even without perfect information, policymakers and community members must consider the risks. This initial research stage examines: (1) the emerging risks posed by the unregulated expansion of data centers, particularly in marginalized communities in California, and (2) outlines key policy recommendations aimed at protecting these communities from the mounting inequities driven by the rapid advancement of AI technologies.

The AI industry is powered by data centers in polluted Californian communities

The tech sector in California produces over $500B in economic output, is the headquarters for several of the largest and most profitable tech companies in the world, and is also home to 32 of the top 50 artificial intelligence (AI) companies worldwide. To better understand which communities in California are most susceptible to potential health hazards associated with data centers, a spatial analysis was conducted of the locations of data center clusters and public health indicators in those locations, specifically examining the existing pollution burden and diesel levels. Overlaying California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment's latest iteration of its environmental map screening tool, CalEnviroScreen 4.0, with Data Center Mapping coordinate datasets revealed a clear correlation between poor public health indicators and clustered data center locations in California. To be clear, this correlation does not prove (nor necessarily suggest) that data centers caused the poor public health outcomes; rather, it is evident that data centers are clustered in already polluted areas with such outcomes.

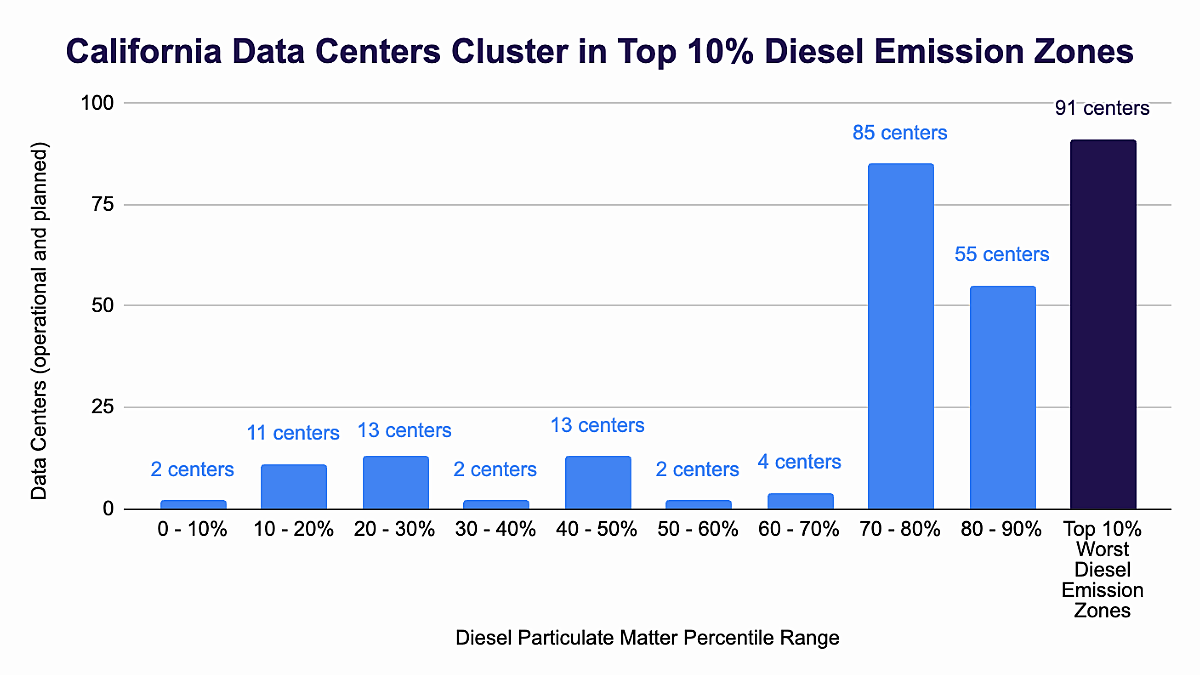

Among the locations of all existing and planned data centers in California, the median pollution burden score is 7 out of 10, with 10 representing the highest pollution burden. Overall, the median pollution burden score of the data centers placed them in the top 20% of the most environmentally impacted locations in the state. Similarly, nearly one-third of all operational and planned California data centers are located in the top 10% of areas most polluted by diesel particulates. Because many data centers use backup diesel generators, generating harmful fine particulate matter (PM2.5), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen oxides (NOx), as well as increasingly using fossil fuels for their energy sources, location is crucial in determining the potential disproportionate scale of pollution impact on communities.

Chart 1.

There is cause for concern. A 2024 paper from researchers at the University of California, Riverside and Caltech found that data centers could contribute to 600,000 asthma-related symptom cases by 2030, with overall public health costs exceeding $20 billion. These findings highlight that the rapid expansion of AI infrastructure poses an emerging public health crisis in the communities where data centers are located and the surrounding areas.

However, in regions already burdened by public health challenges stemming from environmental racism and gentrification, these troubling health impacts will disproportionately affect communities of color and exacerbate existing health disparities.

Bayview-Hunters Point, San Francisco: A “sustainable” data center?

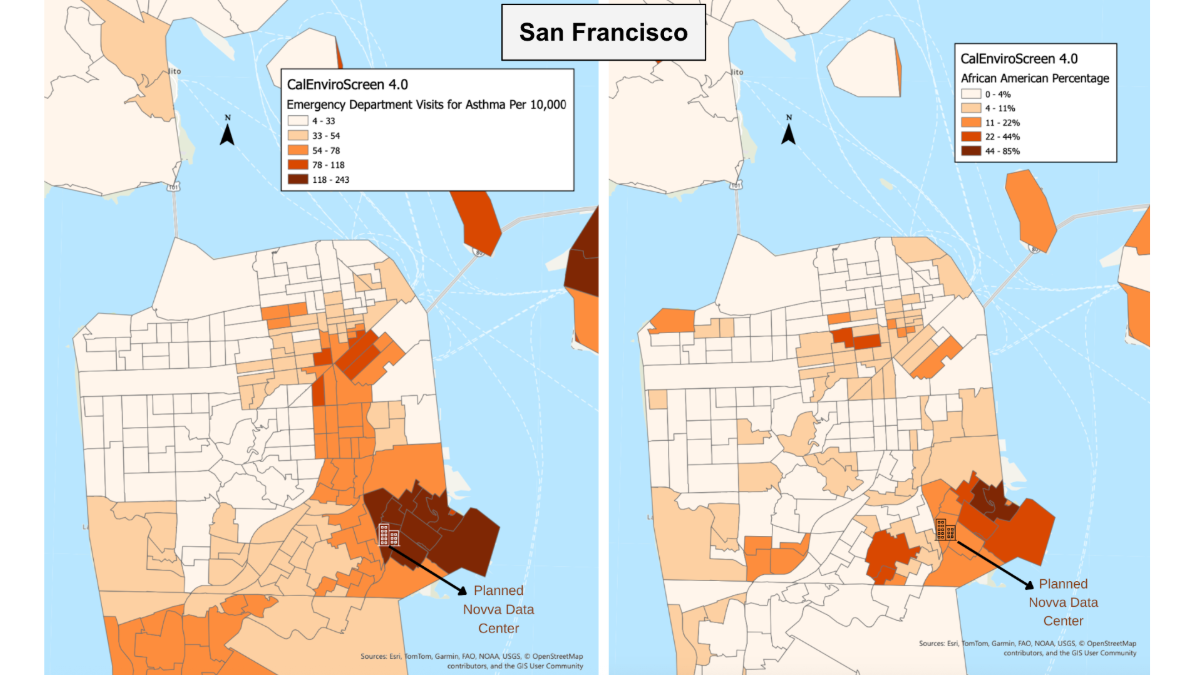

Situated along the San Francisco Bay, Bayview-Hunters Point (BVHP) is a predominantly Black, Latine, and Asian American Pacific Islander community. Due to redlining policies, the Black population in BVHP increased 665% in 1945 alone, and by 1980, 72% identified as African American. However, due to gentrification, inadequate public transportation, and rising housing costs, the Black population in BVHP has significantly decreased since the 1980s, yet it remains one of the most concentrated communities of color in the city of San Francisco.

Once serving as a shipyard during World War II, BVHP has established itself as a center of industrial progress within the city, with nearly 38% of the area zoned for industrial use, compared to about 7% of the entire city of San Francisco. Due to the socioeconomic and environmental cumulative effects of institutional and structural racism, these intentional zoning distinctions have made BVHP one of California's most contaminated and polluted areas. This suggests that persistent air pollution has resulted in reduced life expectancies, high mortality rates from lung disease, and some of the highest rates of asthma-related hospitalizations in San Francisco.

Amidst an already overburdened neighborhood hosting a wastewater treatment facility, diesel truck idling, and industrial rendering plants BVHP is now the host of a colocated and a standalone data center that supports Silicon Valley’s insatiable need for data processing (and the energy it requires). The planned independent center, Novva, has invested $500 million to build a 36 megawatt (MW) powered data center in BVHP, with the first 9MW launching in the summer of 2026. Though this data center is not defined as a hyperscaler and is significantly smaller than those built in communities like Memphis, its presence will still be felt.

Novva, whose model centers on sustainability, coined its BVHP center the “greenest data center ever created in the area.” Novva says it uses hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) as biofuel for its generators, sodium UPS batteries with no thermal runaway risk or rare earth materials, and a waterless data center cooling system.

Novva claims it hopes to achieve “genuine sustainability in data center operations without ‘greenwashing,’” yet its proposed framework overlooks the cumulative environmental and health impact of constructing in a historically marginalized and industrially overburdened community. Novva's claims open a broader discussion about how data center marketing (re)defines sustainability, and although some may commend Novva for its efforts to minimize dangerous byproducts, HVO only reduces greenhouse gas emissions. It is unclear how Novva defines or measures genuine sustainability when factoring in location. Novva did not respond to a request for comment.

While BVHP’s data center attempts to promote sustainability, it exemplifies how such claims remain insufficient, often masking the disparate impacts and other crucial context related to location.

Chart 2. Data sources: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS, OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community.

Location is the number one indicator of community impact

This increased economic interest coincides with a paradigm shift away from renewable energy in favor of rapid data center and gas-powered plant expansion. In the US context, the "Stargate" project exemplifies a major project on an expedited timeline, which has sparked interest from landowners, developers, and local officials nationwide. This trend could fuel development by prioritizing underserved and historically underinvested communities. BVHP is not just an isolated case but part of this broader industrialization pattern in areas already burdened by the lasting effects of environmental and health racism.

While Big Tech and data center companies are announcing commitments to sustainability and contributions to gap-closing initiatives, constructing a sufficient model is undermined if the historical economic, climate, and health-related factors are ignored. For example, although some historically underinvested communities may welcome the promise of job creation from building new data centers, recent reports have revealed that these centers create minimal jobs. Naturally, these benefits would not offset the severe public health and environmental harms imposed on a historically overburdened community. Disregarding location considerations and community transparency may perpetuate a pattern of techno-industrial solutionism, reproducing the harms communities like BVHP have faced for generations.

The impacts of data centers extend beyond their physical locations. To fully evaluate these broader impacts, examining the power source of data centers, such as sourcing energy from power plants, is necessary to properly evaluate their overall environmental and public health impacts. As states race to provide energy for data centers, state legislatures have proposed converting closed coal facilities in predominantly communities of color into gas power plants and expanding nuclear power, largely incentivized to support data centers’ energy needs. Other planning models and initiatives indicate data center site selection possibilities in predominantly Black areas.

As a result, we cannot have a sustainable model when location is viewed as neutral, and data centers exacerbate detrimental location-specific factors, particularly in or adjacent to already vulnerable communities of color.

Recommendations

Learning from historical patterns is critical to understanding how we can shape development and policy regarding data center expansion through a more nuanced and contextual lens. The concentration of data centers in vulnerable areas is not a new phenomenon, as we have seen e-commerce factories transform low-income neighborhoods into major transfer hubs for truck deliveries. Examining replicative industrial placement patterns is a way to learn from past and ongoing advocacy, which can help inform the path forward to address this emerging public health and environmental crisis. As hyperscaler data centers proliferate in the US, along with increased regulatory attention and pressure, these recommendations will be most effective in addressing the impacts of data centers, specifically hyperscalers.

City and state-level policy interventions:

- Update outdated industrial zoning classifications: When analyzing spatial clustering of data centers, it is crucial to consider industrial zoning regulations, such as those in the BVHP majority industrial zoning area. City zoning plans often paint a larger, historical picture of where sacrifices have been made for pro-business investments, accumulating and normalizing poor location decision-making at the expense of community health. Data center clustering reveals a deeper issue within longstanding zoning policy, and this unprecedented expansion offers an opportunity to reassess how industrial zoning adversely affects community agency and health quality. Increased community input and engagement across the country has led to stricter zoning ordinances, underscoring that public engagement and decision-making power are essential to ensure that centers adopt a harm-reductive, location-centered approach that does not exacerbate existing inequalities or contribute to cumulative impact.

- Increase informed public decision-making power: Data center development proposals have mobilized community pushback, with community leaders claiming that the infrastructure will perpetuate harm by eliminating environmental considerations and contributing to already precarious cumulative air pollution. However, data centers and Big Tech obtaining public consent does not equate to community-informed decision-making power or transparent dialogue. State and local governments should conduct health impact assessments before a data center is constructed, and the results should be publicly accessible to both community members and leaders. These assessments can inform the community about potential health risks, and community leaders should be actively involved in discussions and decision processes leading up to construction decisions.

- Mandate reporting and increase transparency: Data centers must have increased transparency standards for adequate community-informed action and mobilization before and after the data centers are built. States like California have introduced legislation, such as AB 93 and AB 222, for transparency and accountability, proposing greater energy and water use transparency from AI developers and data center operators. To understand the long-term health implications, particularly for communities like BVHP, increasing mandated transparency indicators could enhance public health and environmental research capabilities, paving the way for informed community impact, mobilization, and public awareness regarding the ramifications of data centers on host communities.

Conclusion

Black, low-income Americans already have the highest mortality rate from exposure to PM2.5, a type of air pollution produced by electricity generation. Data centers moving into predominantly communities of color and low-income residential areas can exacerbate historical trends that overlook community health for industrial needs; choosing locations as sacrifice zones, creating public harm for private gain that disproportionately affects minority health in the name of technological innovation.

AI infrastructure may exacerbate past harms that previous fossil fuel industries have imposed upon communities of color, excusing its extractive and harmful impacts in the name of progress and innovation. Although the challenges of implementing clean energy efficiency for data centers while advancing AI capabilities remain necessary and clear, we must also consider multi-pronged analyses of risks and harms to local communities, and incorporate prior data on health and environmental inequities, to minimize the sociotechnical consequences of the digital economy.

Authors