Latin America’s Children at Risk on Facebook: Predators Stalk Children in Celebrity Fan Groups

Lara Putnam / Feb 26, 2025The below analysis by Lara Putnam is published by Tech Policy Press in tandem with a series of independent reports coordinated by the investigative journalism consortium EL CLIP and published by EL CLIP, Chequeado, Crónica Uno, El Espectador, and Factchequeado. Learn more about the collaboration here.

I am a professor of Latin American history and Director of the Civic Resilience Initiative of the Institute for Cyber Law, Policy, and Security at the University of Pittsburgh. I am also a mother of four: my older children were born and raised in Costa Rica, where we lived for nearly a decade and I taught at the main public university. In my research, I study various phenomena related to social media. In 2022, I published an account of my failed efforts to get Facebook to remove public Spanish-language groups in which children were being openly targeted for online sexual exploitation in Wired.

Eventually, in the months after publication, those specific groups disappeared. However, in 2023, I stumbled into a new set of public groups permeated by the same type of content. These were framed as fan groups for the Mexico kid hip-hop trio Los Picus. I wrote an initial report on the phenomenon in Tech Policy Press last January.

In this update and extension of that work, I report that the scope of the problem is far greater than I had initially found, encompassing multiple different fandoms and many dozens of public Facebook groups with over two and a half million members. Groups that center around popular celebrities, such as YouTube stars Mau McMahon and Karla Bustillos and the child members of their household; Phoenix, Arizona-born teen entertainer Xavi; and K-Pop stars, become host to what appears to be child predation.

The groups I have identified likely represent just a fraction of the problem. In addition to my own research, over the past few months, five journalists in Spanish-language news organizations in Latin America, coordinated by the investigative journalism consortium El CLIP, looked into these phenomena. Today, they published their reports in El CLIP, Chequeado, Crónica Uno, El Espectador, and Factchequeado. Their reporting indicates that this problem extends to even further Facebook groups—many not associated with any fandom, but rather branded as places to discuss teen issues— that the legislation in the countries investigated is often insufficient to deal with this sort of digital grooming, and that Meta collaborates too little with local authorities to try to curb this behavior.

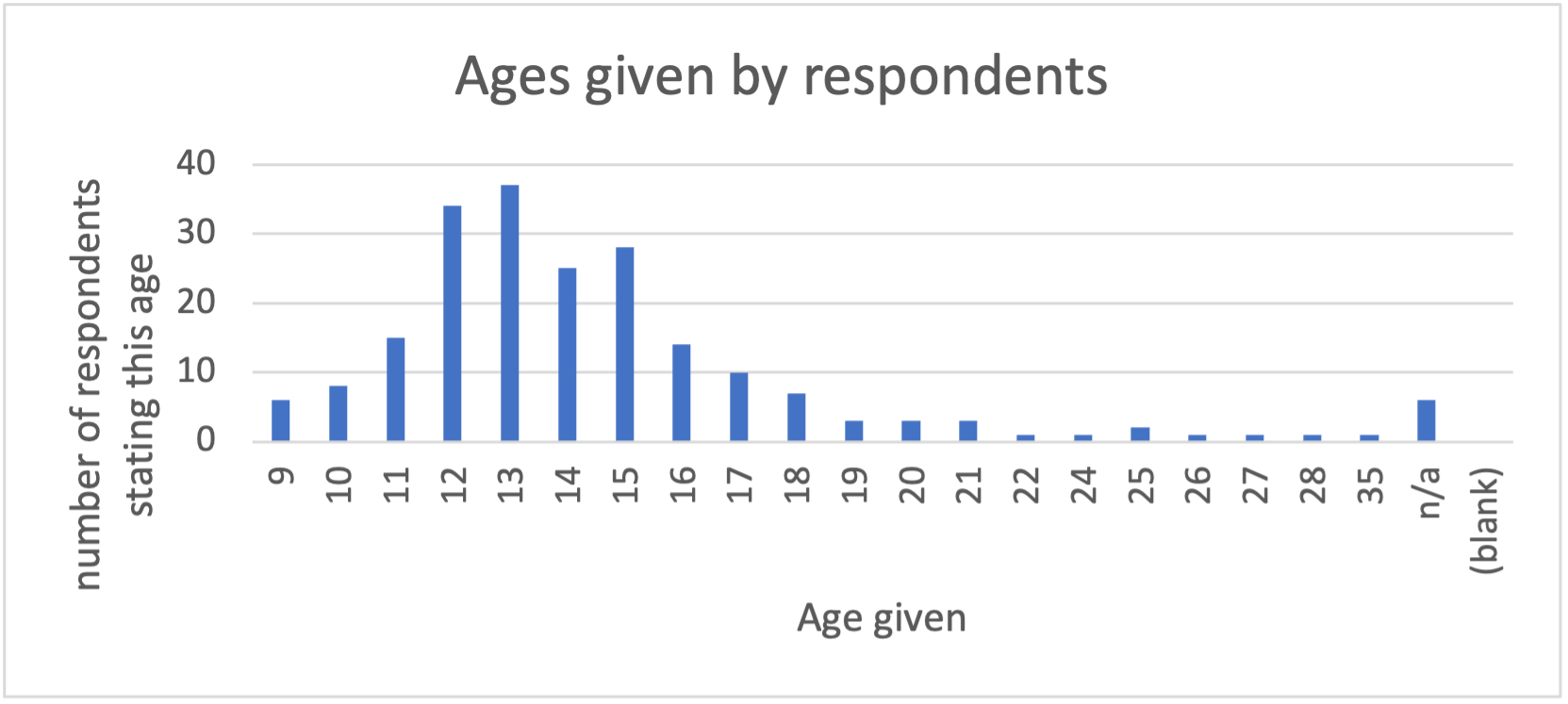

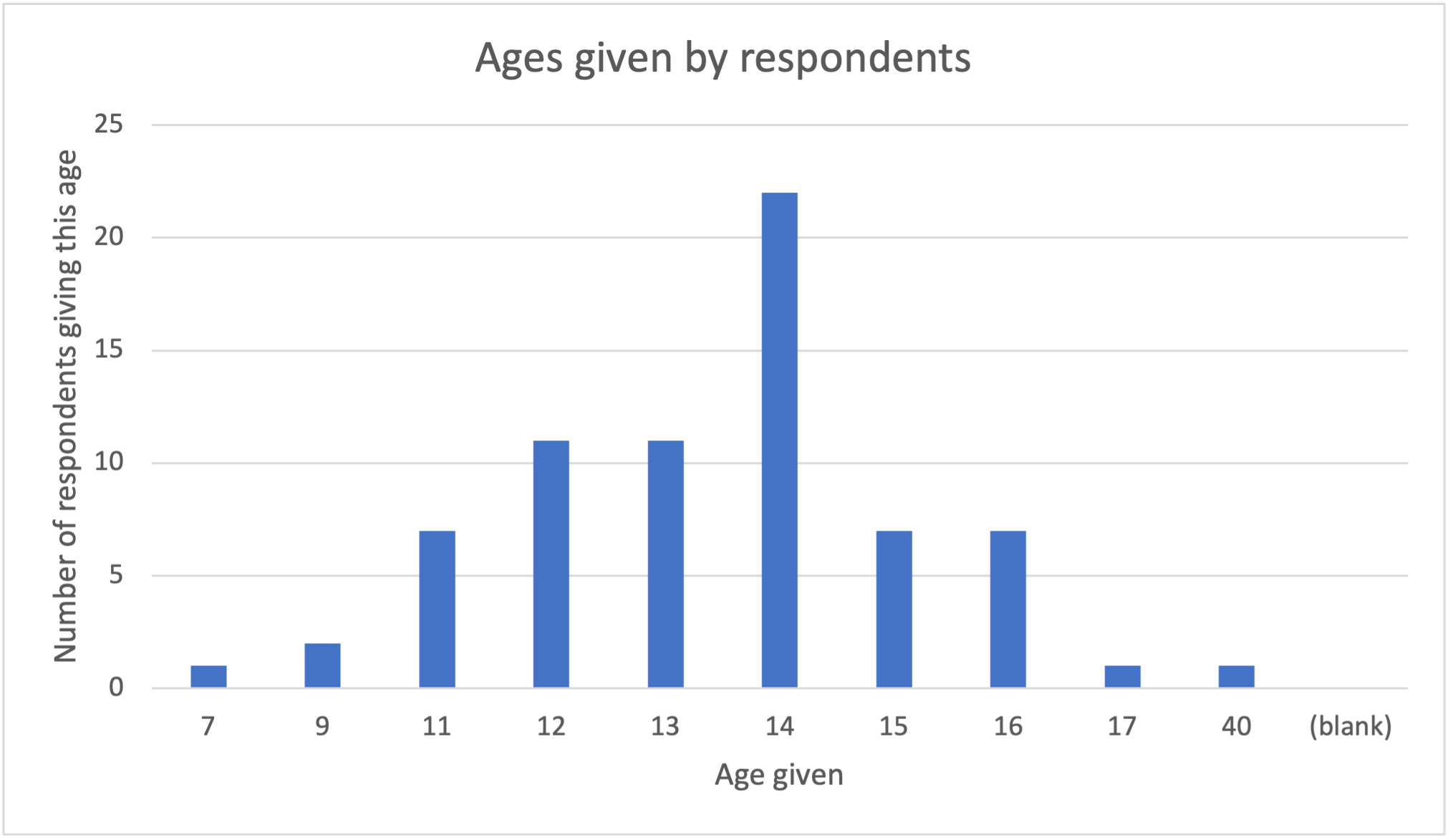

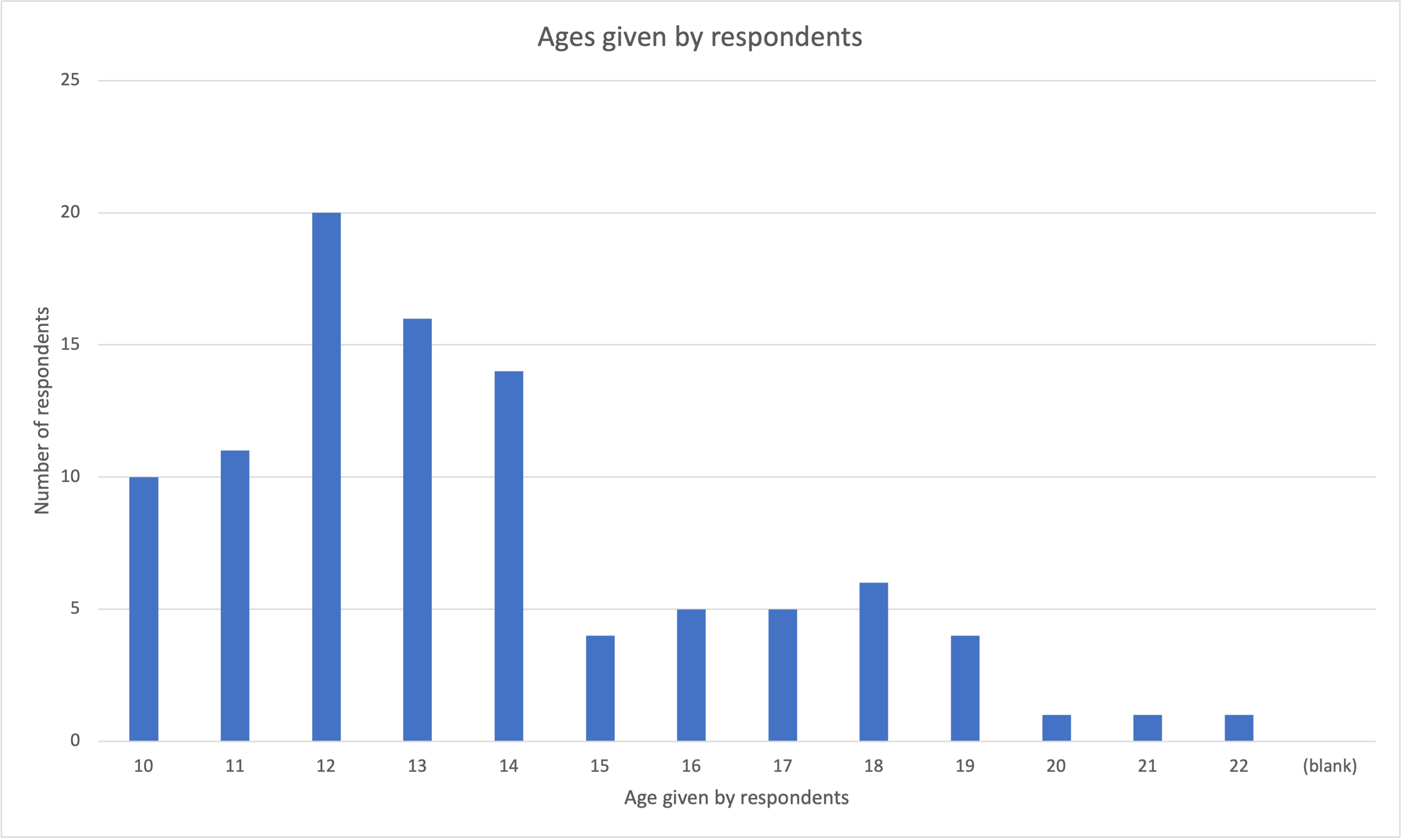

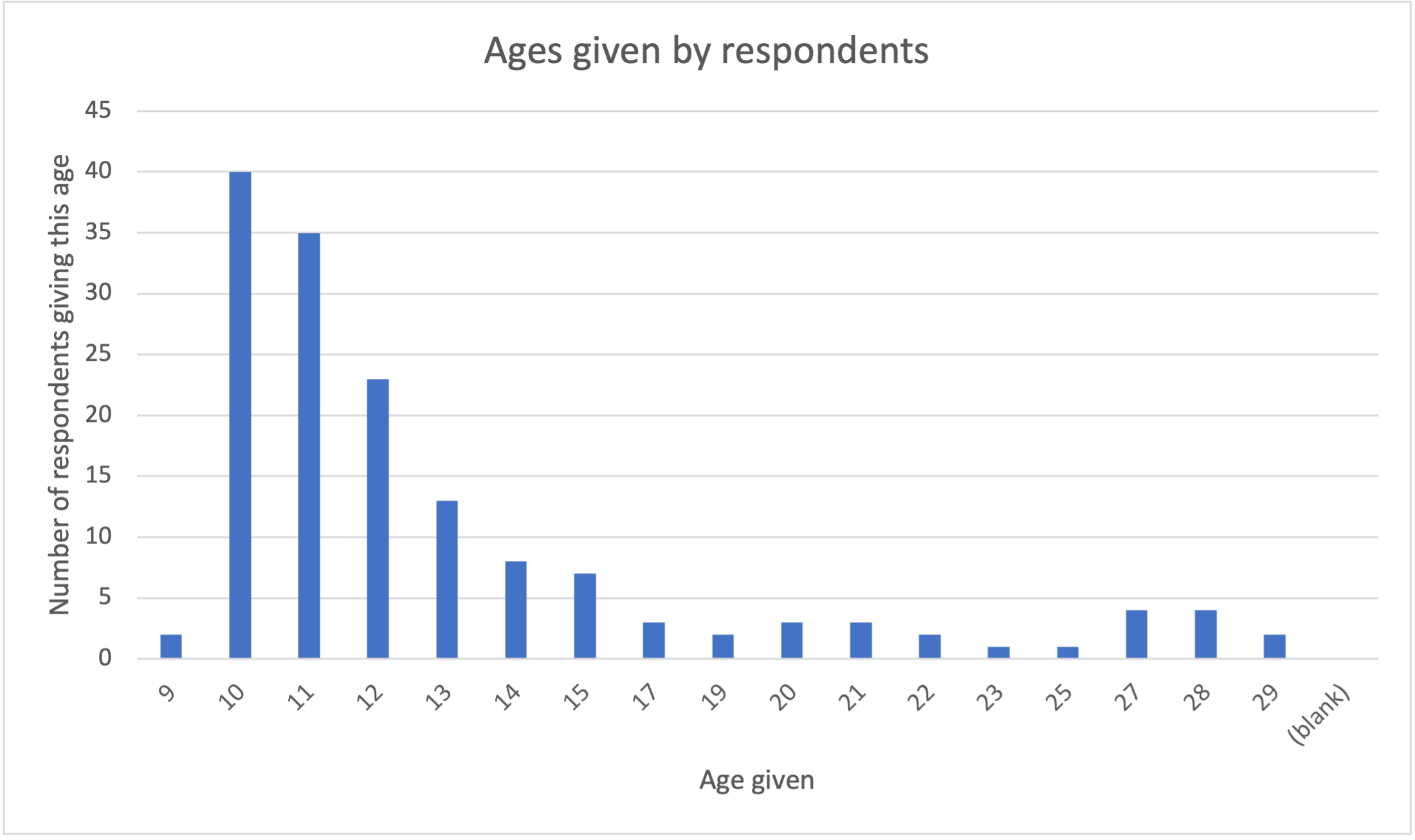

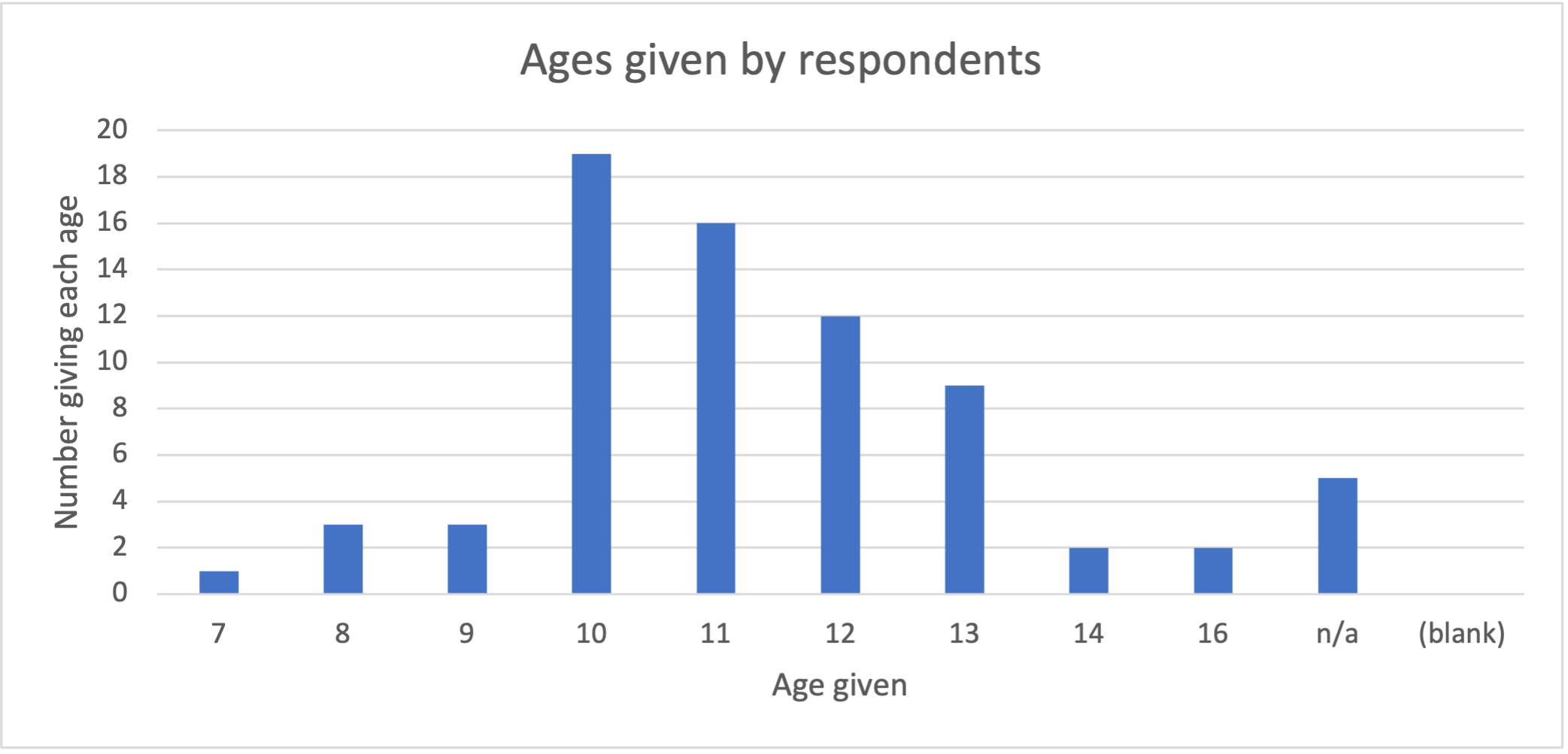

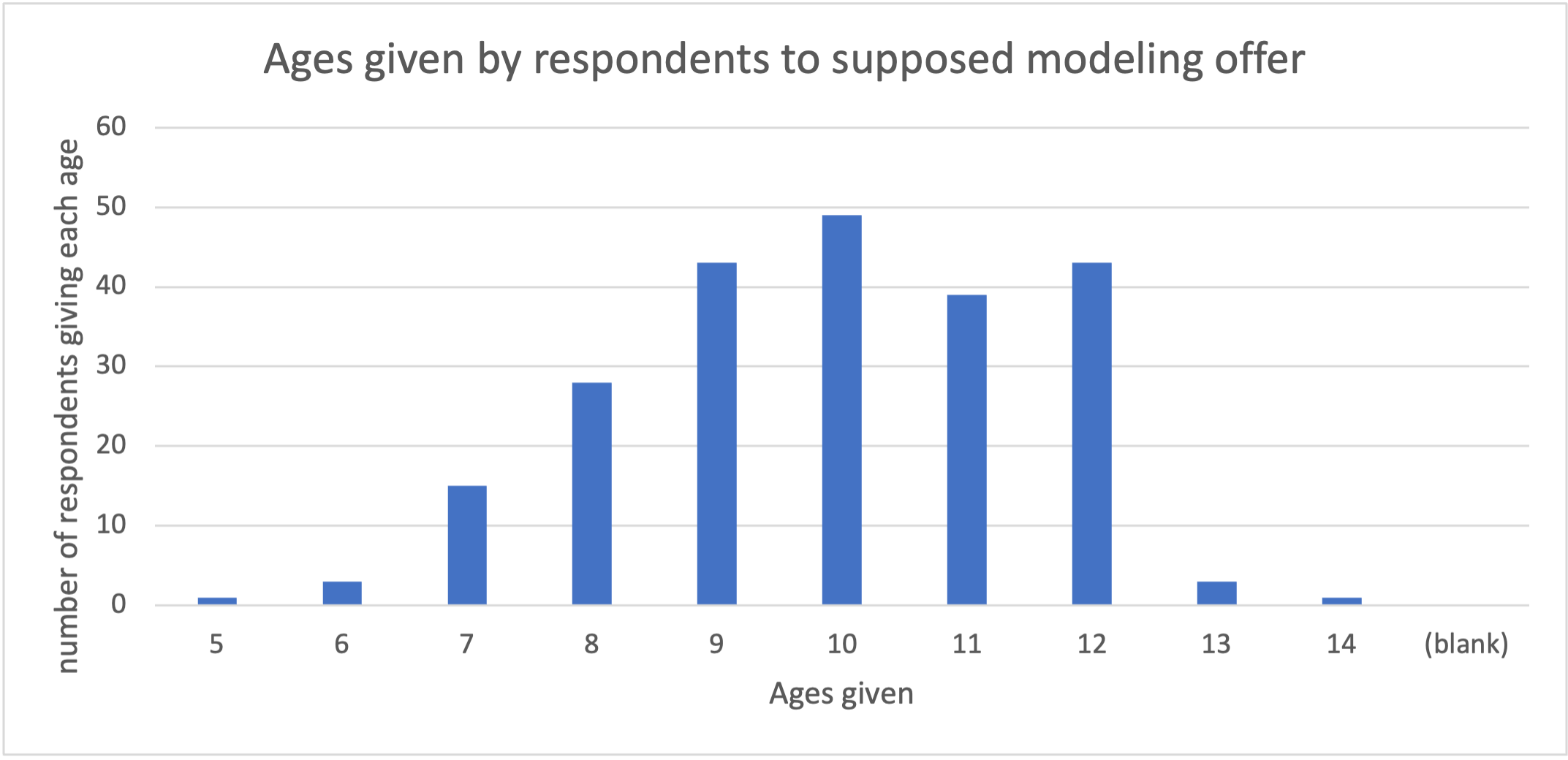

In this report, I use the fact that posters in these Facebook groups sometimes ask participants to post their age and country of origin to provide rough quantitative data on the regional spread of stated ages and national origin. Numerous accounts in these groups identify themselves as children from Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, with others from across the hemisphere. Accounts identifying as children as young as 7 and 8 are present, and 10, 11, and 12-year-olds are common.

Towards the end of this report, I look in detail at some of the interactions in comments within these—again, fully public—groups to describe some forms of emotional luring and manipulation that very young Spanish-speaking Facebook users are apparently subject to.

We presented a range of questions to Meta about these phenomena. A Meta spokesperson responded with a statement and provided a link to Meta’s proactive steps to address these and similar phenomena:

Child exploitation is a horrific crime. We work aggressively to fight it on and off our platforms and to support law enforcement in its efforts to arrest and prosecute the criminals behind it. Our policies prohibit child exploitation, inappropriate interactions with children, and the sexualization of minors; these rules apply globally, in different languages, including English and Spanish, and across each of our platforms. While predators constantly change their tactics to evade detection, our global teams and tools work to identify and quickly remove violating content.

Please note that the report below contains disturbing descriptions and screenshots of posts and interactions involving accounts identifying as children. These images have been edited to remove any information that could be used to identify a particular account or user identity.

Spanish-speaking children on Facebook: a target for predators?

More Spanish-speaking children may be using Facebook than any other language group of children in the world. Latin America's total under-18 population is around 200,000,000, nearly three times the size of the same age group in the US, and the overall Facebook utilization rate in Latin America (78% of the population) is nearly as high as in North America.

Has this scale made the pool of Spanish-speaking children using Facebook groups a systematic target for child predators? My research suggests the answer may be yes—and that so far, Meta has been unable or unwilling to put the brakes on this trend.

In the public Facebook groups I observed in my research, accounts that identify as children interact with individuals seeking to entice them to “friend” them and thus enable private messaging. Experts have noted the systematic dangers created by the fact that Facebook combines, within one platform, a public interface within which children can be found and engaged and a private channel to which that relationship can be seamlessly moved, through which children can be lured into virtual sexual interaction: pressured to provide photos or livestreams in which they expose or touch themselves or others. (It should be underlined that this would constitute child sexual exploitation or abuse even if the interaction with the offending adult is wholly online and would be deemed criminal not only by US federal and state law but multiple international conventions.)

The challenge created by a world in which camera-enabled smartphones with social media access are routinely in children’s hands is that kids can now be manipulated into doing harmful things to themselves and each other by people who live hundreds or thousands of miles away. Exposure to this risk is not small: surveys by Mexico’s public Federal Telecommunications Institute have found that over a third of Mexican children aged 7-11 use Facebook, and over two-thirds use WhatsApp, the fully encrypted private messaging system also owned by Meta.

Meta policies focused on stopping the on-platform spread of images that constitute CSAM (child sexual abuse material: the kind of material formerly referred to as “child pornography”) appear to be a poor fit for these dangers. Posts that parents or people who work with children would immediately see as potentially endangering may not even be violative under current platform policies.

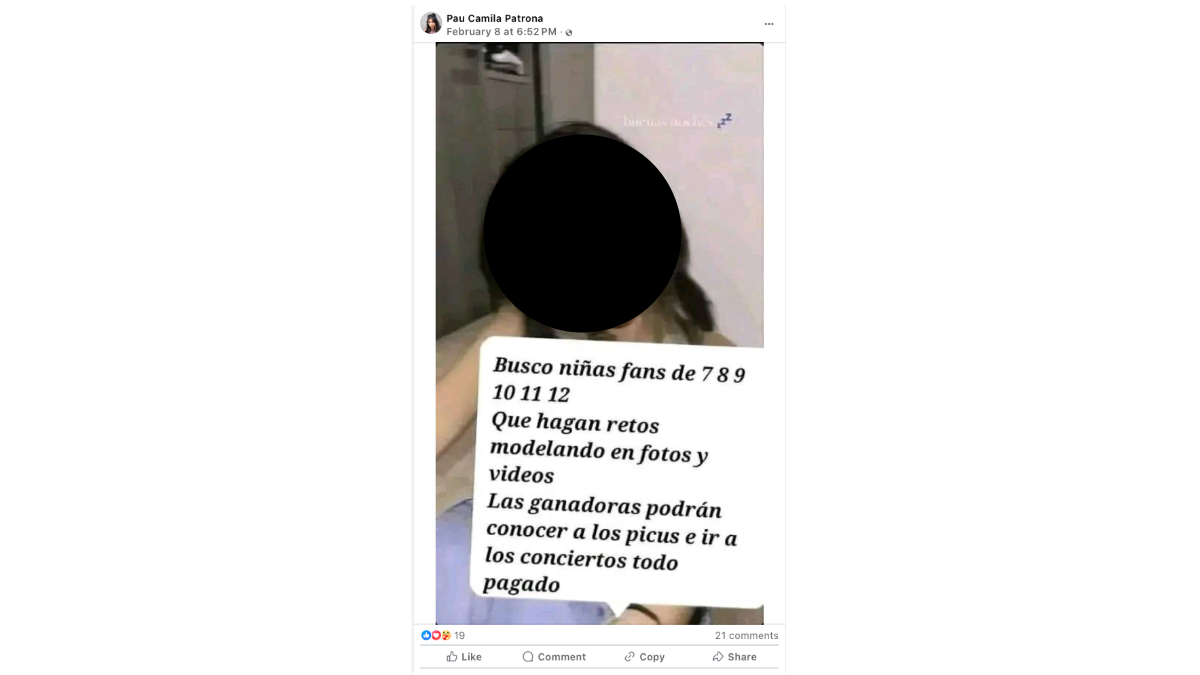

Consider the two images here. (In this case, the posting accounts are impersonating child celebrities and so are technically violative for that reason, but that itself rarely triggers takedowns. Because these child stars’ photographs are presumably being used without their consent, we have blocked their faces here.)

A post in a Facebook group from an account falsely purporting to be Los Picus-linked celebrity Paula Cacho.

The above post is from an account pretending to be Picus-linked celebrity Paula Cacho (who has 1.7 million followers on Instagram and 5 million subscribers on YouTube). It reads “I am looking for girl fans 7 8 9 10 11 12 years old, to do dares and model in photos and videos. The winners will get to meet the Picus and go to concerts with all expenses paid.”

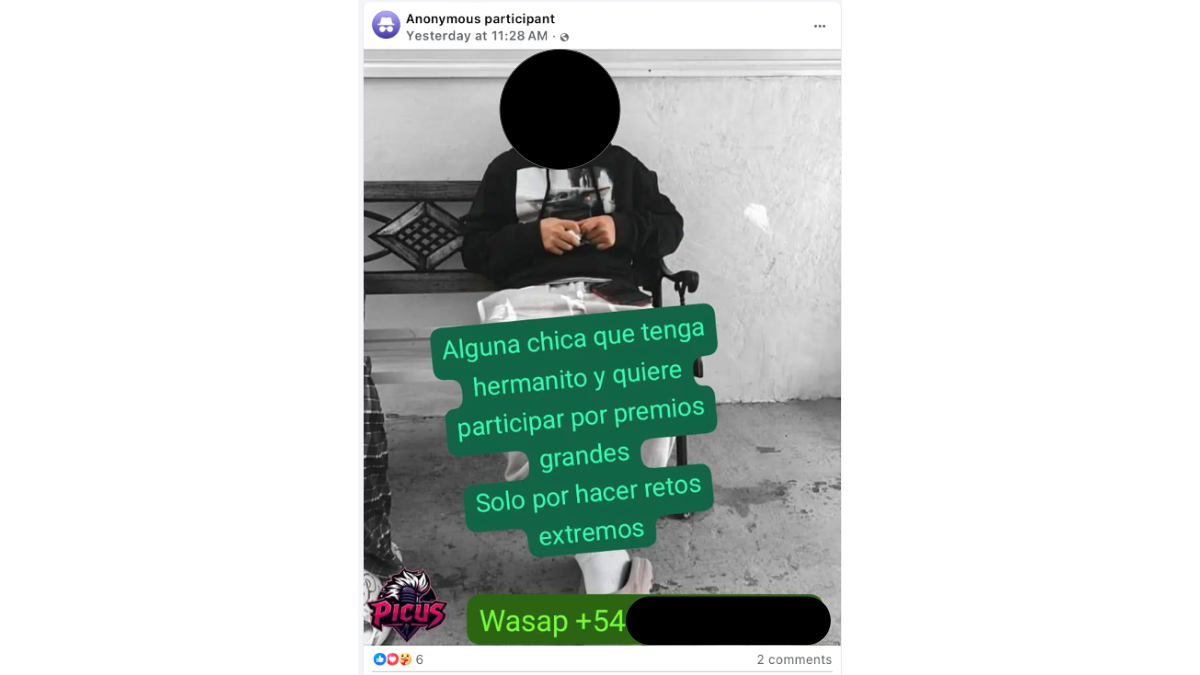

The below post uses a photo of one of the Picus brothers, and reads: “[Looking for] a girl who has a little brother and who wants to participate for big prizes, just by doing extreme dares.” The post includes a WhatsApp number, typical of the way that those seeking to engage children in these Facebook groups openly aim to steer communication into encrypted private channels.

A post in a Facebook group uses a photo of one of the Picus brothers and includes a WhatsApp number.

In cases where the people interacting in these groups are teenagers—an age many societies see as appropriate for romantic exploration—categoric judgment becomes complex. This is reflected, for instance, in the fact that in the US, many modern statutes regarding the “age of consent” differ not only based on the young person’s age but the age gap between participants in a relationship. For instance, in my state of Pennsylvania, no one under the age of 13 is considered legally capable of consenting to sexual activity, while teens between 13 and 15 years of age can only consent to sexual activity with individuals who are less than four years older than them.

Similarly, when dealing with online interactions, teenagers’ sharing intimate imagery with peers their own age defies simple judgment. However, it is crucial to note that online, far more easily than in-person, interactions that teens perceive as consensual may be based on a falsehood or may open the door to non-consensual encounters. (For examples of systematically deceptive predation by adults impersonating teens, see, for instance, reporting on organized “sextortion” schemes run for profit by networks in different parts of the world). There is thus good reason to be concerned about the harms and risks faced by teenagers, especially younger teenagers, in the groups described below.

However—and without seeking to minimize the importance of teenagers’ exposure to adult sexual predation online—in the assessment that follows, I put special emphasis on the presence and experiences of accounts self-identified as children under 13. They simply should not be in these spaces facing these risks at all. Facebook’s platform policies prohibit children under 13 from using the platform. Indeed, a Meta spokesperson confirmed that “People under 13 are not allowed on Facebook and we use a range of tools to identify, review, and remove underage users.” Various legal compliance regimes facing Meta, including the US and EU, require different standards of care and privacy protection for websites directed to children under 13 years of age.

But if the question is “how well are supposed safety measures working in practice?” then the open presence on the world’s largest social media platform of adults seeking to engage children 12 and younger is of particular concern.

Incentivizing children to engage: patterns emerge

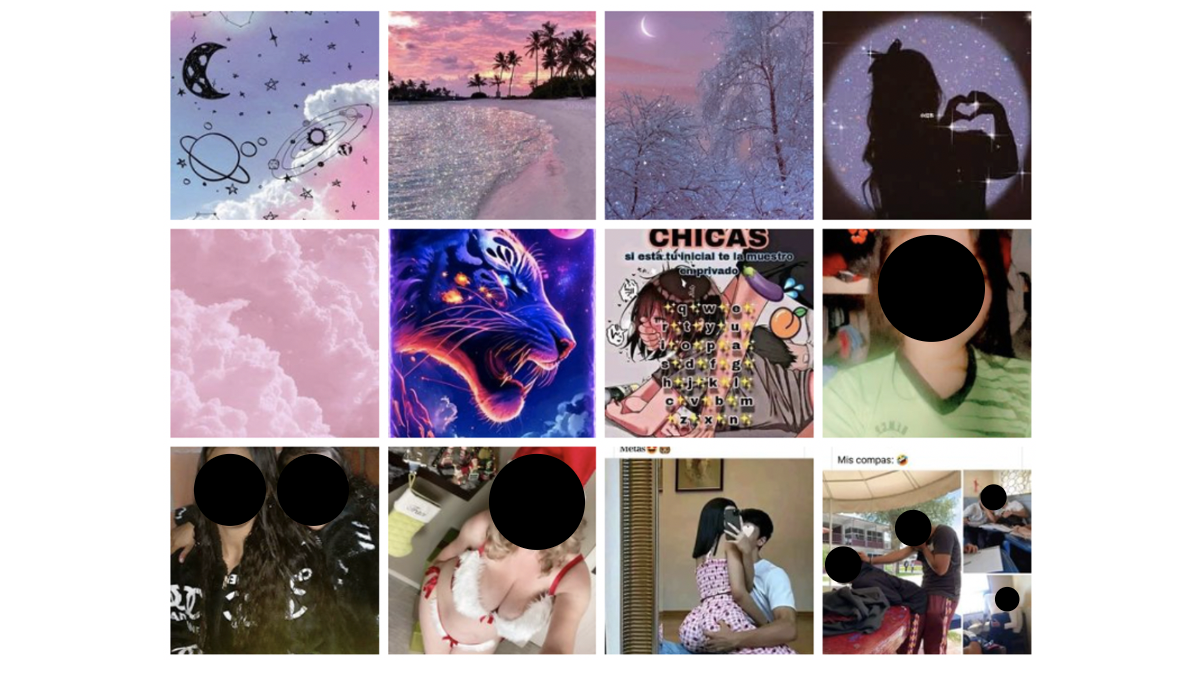

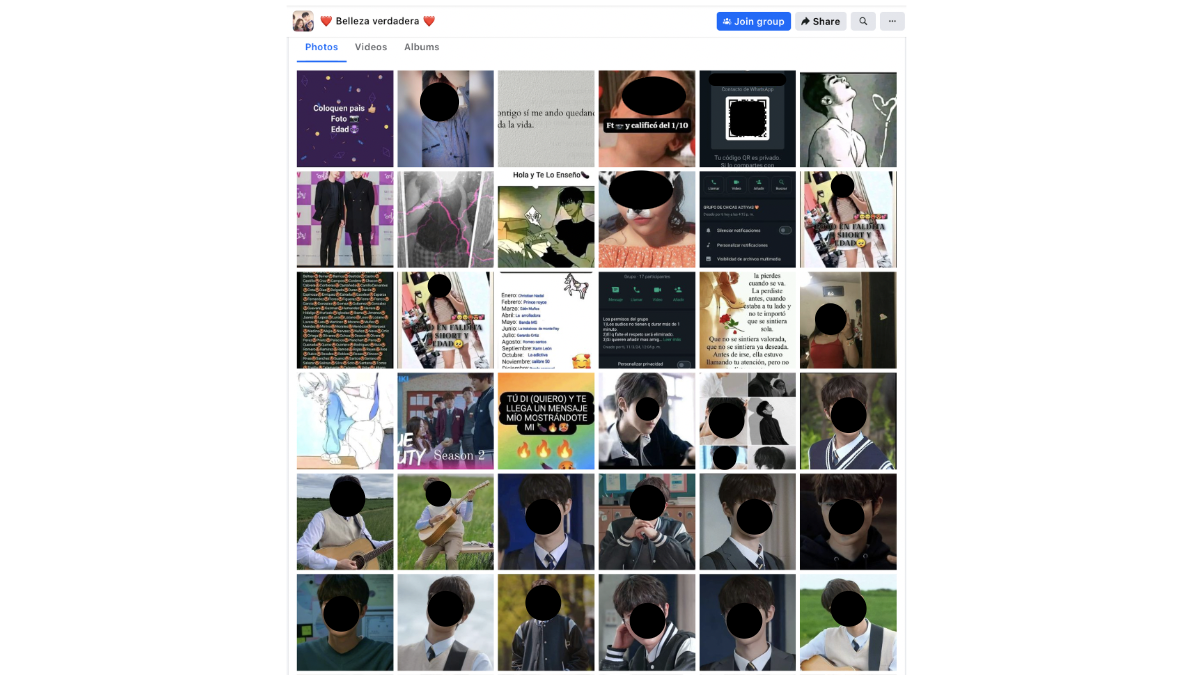

A screenshot of the “recent media” displayed in one Facebook group with 116,000 members.

Above is a screenshot of the “recent media” displayed in one Facebook group with 116,000 members, nominally geared around smartphone wallpaper sharing, taken in February 2024. The media ‘recently shared’ includes a mix of cute pastel backgrounds, explicitly sexual engagement-seeking posts (“GIRLS if you see the first letter of your name I’ll show it to you in private [eggplant emoji]”), links to videos showing sexual interaction that seem like they may depict youths under 18, and adult porn.

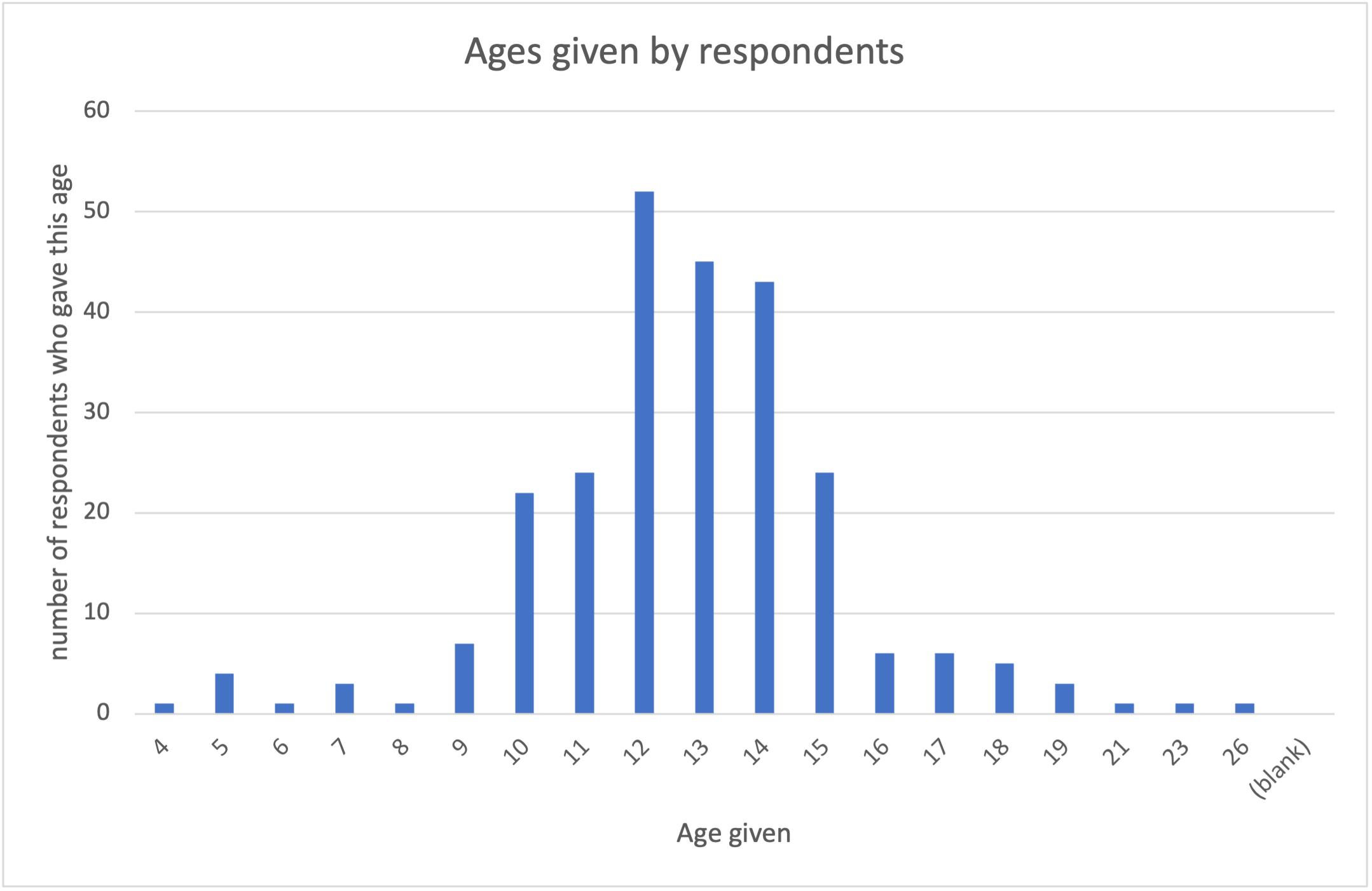

This group appears to have participants ranging from young pre-teens to young adults. We can begin to assess this by looking, for instance, at a post asking group members to post their photos, ages, and countries, which yielded 207 responses: 63 of them from accounts identifying as children aged 9 to 12.

Number of accounts identifying as children 12 or younger by country: Mexico (19), Venezuela (17), Cuba (8), Colombia (6), Peru (3), Nicaragua (2), Honduras (2), USA (1), Argentina (1), Chile (1), Guatemala (1), Republica Dominicana (1), n/a (1). Grand total: 63

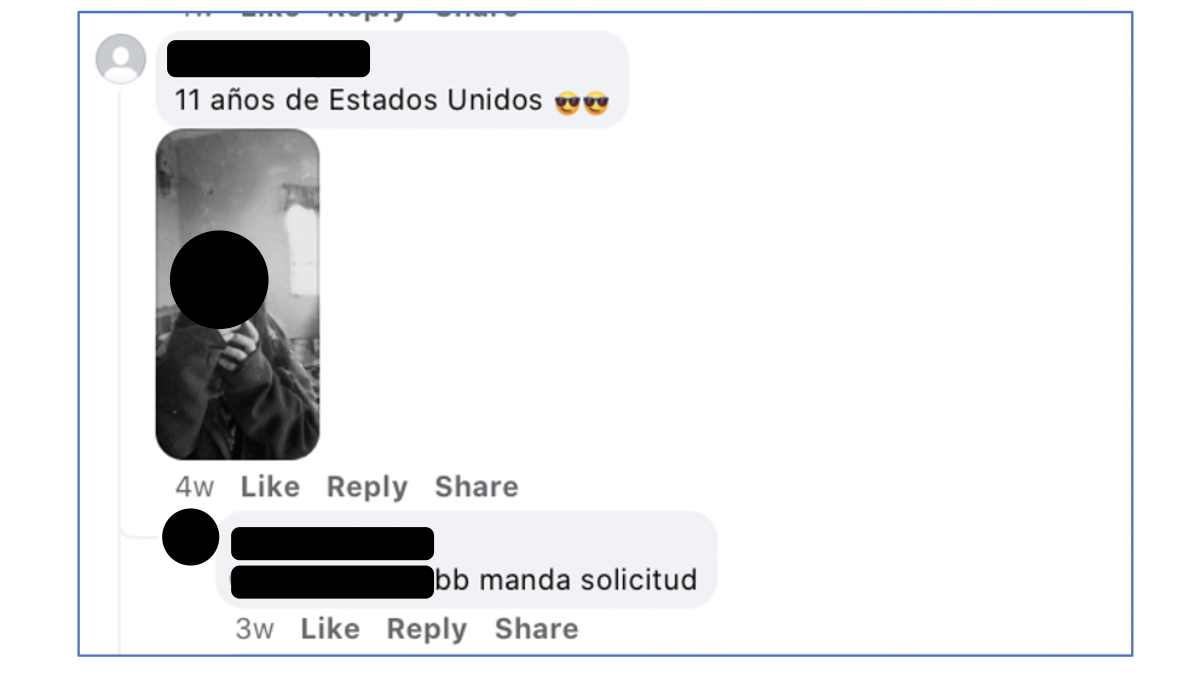

Below is a screenshot of the response from a user who described themself as an 11-year-old from the US. Someone has replied, “Baby, send a request”— that is, send a Facebook friend request so that I can contact you directly on Messenger. Such interactions are common in responses to posts seeking age-specific responses, making it obvious that strangers seeking private interaction with children are routinely able to bypass the safeguard provided by Facebook’s default setting (announced with fanfare in January 2024) that prevents adults who are not already Facebook friends from messaging users under the age of 16: firstly, because users under 13 seem to be openly present in groups such as this one in significant numbers (comprising nearly a third of respondents to this post, for instance) and secondly, because persuading child and teen users to add strangers as “friends” appears to be trivially easy for actors whose goal it is to do so.

A screenshot of the response from a user who described themself as an 11-year-old from the US.

Another example of a teen/pre-teen-oriented group that has been swarmed by posters seeking sexualized engagement is a 360,000-member group nominally for fans of the South Korean high school drama TV series, “True Beauty.” The screenshot of “recent media” from the group, below, taken in February 2024, shows a mix of stills from the show, explicitly sexual cartoons, self-photos nominally uploaded by child users, and posts trolling for sexual engagement (“Say (I want it) and you will get a message showing you my [eggplant; flames; sweat emojis]). Posts to the group routinely also include links to adult porn and apparent CSAM videos, with the standard phrase offering to share (“yo si lo paso”).

"Recent media" in a 360,000-member group nominally for fans of the South Korean high school drama TV series, “True Beauty.”

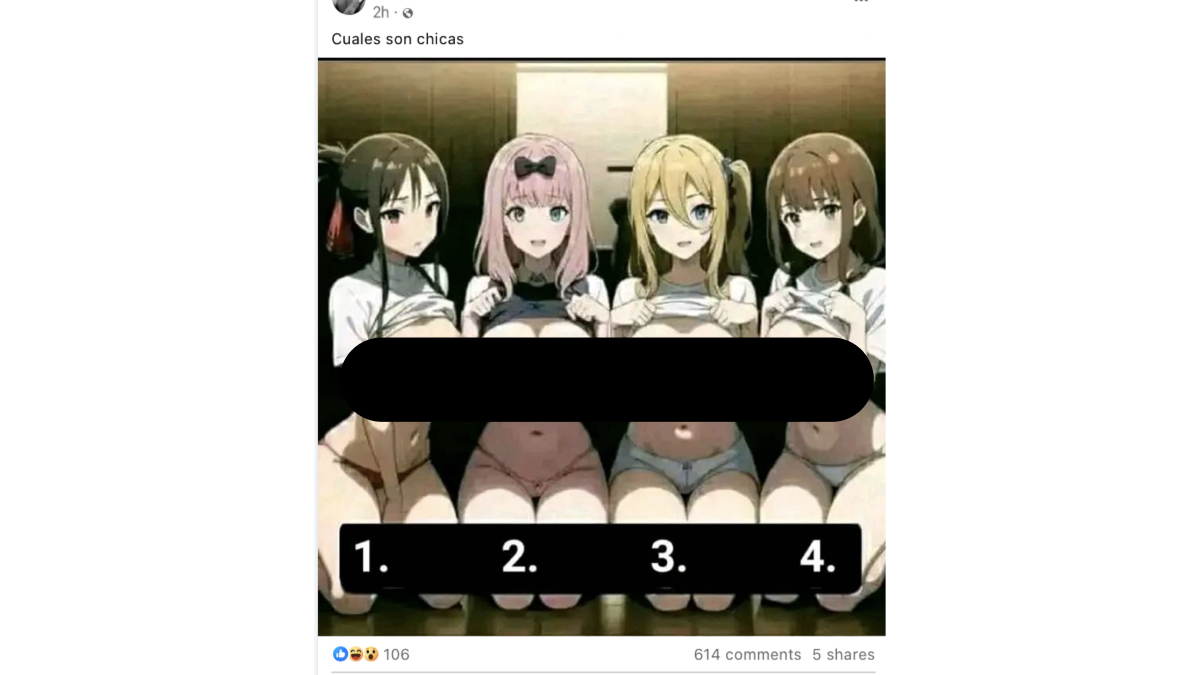

The term “teen dating groups” is sometimes used to describe Facebook groups where young people spend time seeking to make personal connections with each other. That label would fail to convey the prevalence of graphic sexual content—often in the form of cartoons, which apparently do not trigger automated takedowns. In contrast, photographic or photorealistic child nudity usually does. Thus, we see, for instance, cartoons like that with four girls or women showing their breasts, below, posted with the query “Which are you, girls?”, which had over 600 replies when screenshotted.

A cartoon of four girls or women showing their breasts posted in a Facebook group with the query, “Which are you, girls?”

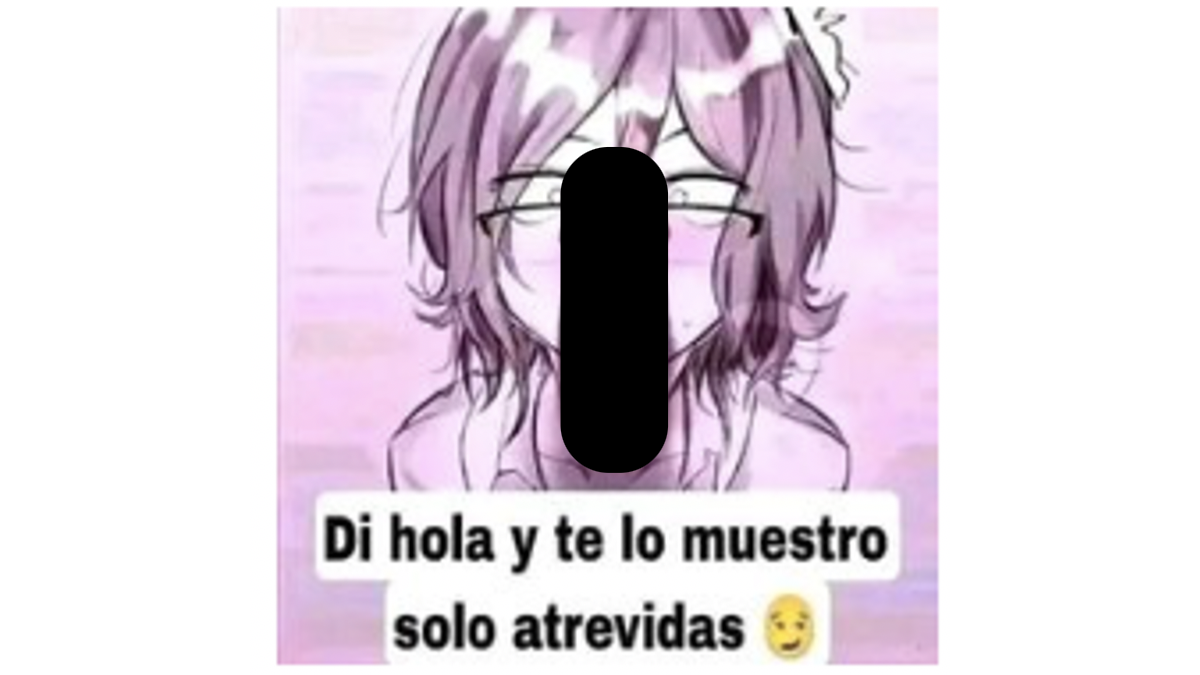

Another example is the below image of the shadow cast by an erect penis on a girl or young woman’s face, which was posted with the text “Say hi and I will show it to you; only daring girls.”

An illustration posted to a Facebook group depicting the shadow cast by an erect penis on a girl or young woman’s face, posted with the text “Say hi and I will show it to you; only daring girls.”

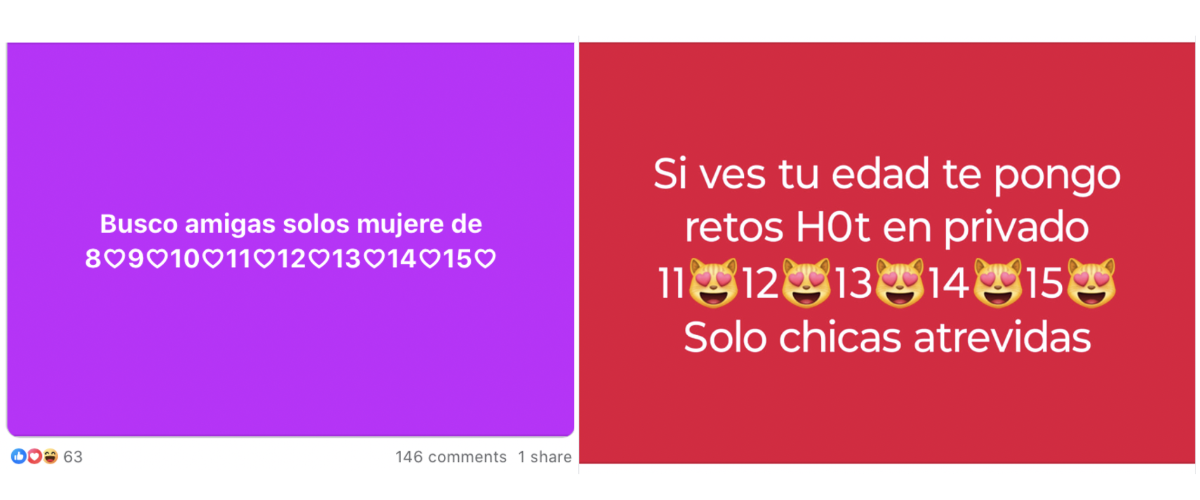

The label “teen dating groups” would seem all the more euphemistic given that it is clear that many posters appear to be looking explicitly not for teens but for pre-teen children. Posts like those screenshotted below, which spell out the ages from which the poster is seeking engagement, offer grim insight into who posters think may reply. “I am looking for friends only women of 8-9-10-11-12-13-14-15,” reads the top one. (As with many such posts, weird missteps of spelling and grammar suggest the author may not speak Spanish natively). “If you see your age I’ll send you dares privately 11-12-13-14-15 Only daring girls,” reads the latter.

Images posted to Facebook groups that spell out the ages of children and teens from which the poster seeks engagement.

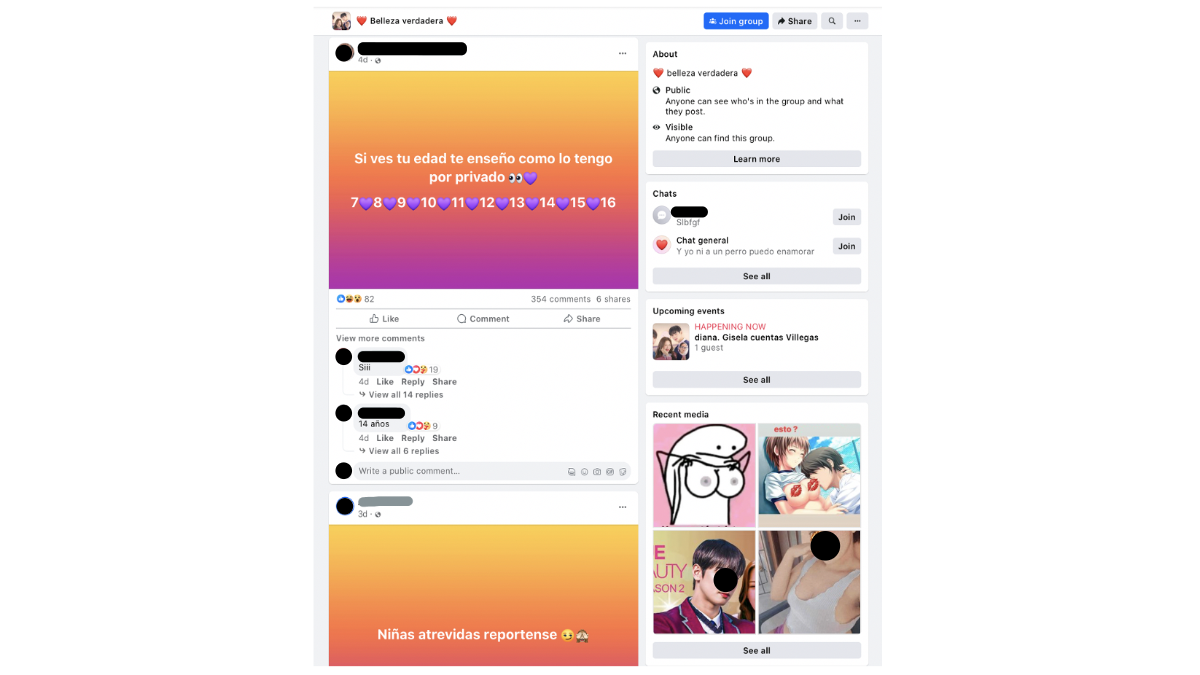

And indeed, there are clearly multiple accounts that identify as pre-teens within the group. For instance, of the 70 individuals who responded to the following post—which reads, “If you see your age, I’ll show you the state of my [implied: penis]: 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16”—30% said they were twelve or younger.

A post in a Facebook group reads, “If you see your age, I’ll show you the state of my [implied: penis]: 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16.”

What appears to be an even younger array of respondents engaged with the post shown below, in which the author wrote—surrounded by heated face, flame, and heart emojis—“Girls: photo and age. The youngest one wins.”

A post on a Facebook groups reads, "Girls: photo and age. The youngest one wins."

In this case, of the 250 respondents who gave ages, nearly half (46%) said they were twelve or younger.

One might think there cannot really be 5-year-olds participating in this group on Facebook and suspect those replies, counted above, must perhaps be typos for an intended response of 15. But at least in one case, the poster typed out, “Yo temgu sinco bero mo me bejan subil fobo” (that is, with many misspellings: “I am five but they don’t let me post photos”). It is worth noting that surveys by Mexico’s public Federal Telecommunications Institute have found that nearly half of Mexican children aged 3-5, just like nearly half of Mexican children aged 6-8, post on social media.

Nevertheless, any given poster describing themself as a child may be lying about their age, just as adults seeking to build sexual relationships with children whom they meet online routinely lie about their age or gender. However, the frequency with which large portions of users across multiple fan groups self-identify as 9, 10, 11, or 12-year-olds (and share photos consistent with those ages) leaves little room for doubt that there are simply many, many actual children participating in these groups: which, again, would be fully consistent with Mexican government survey data regarding pre-teen Facebook usage.

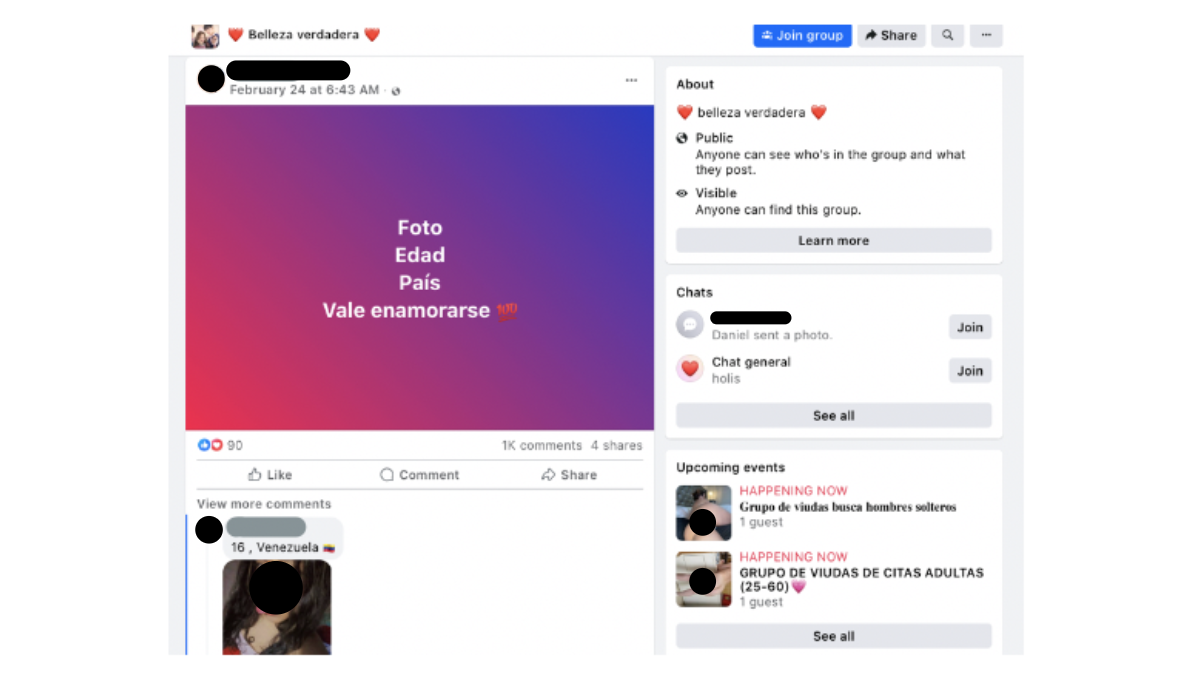

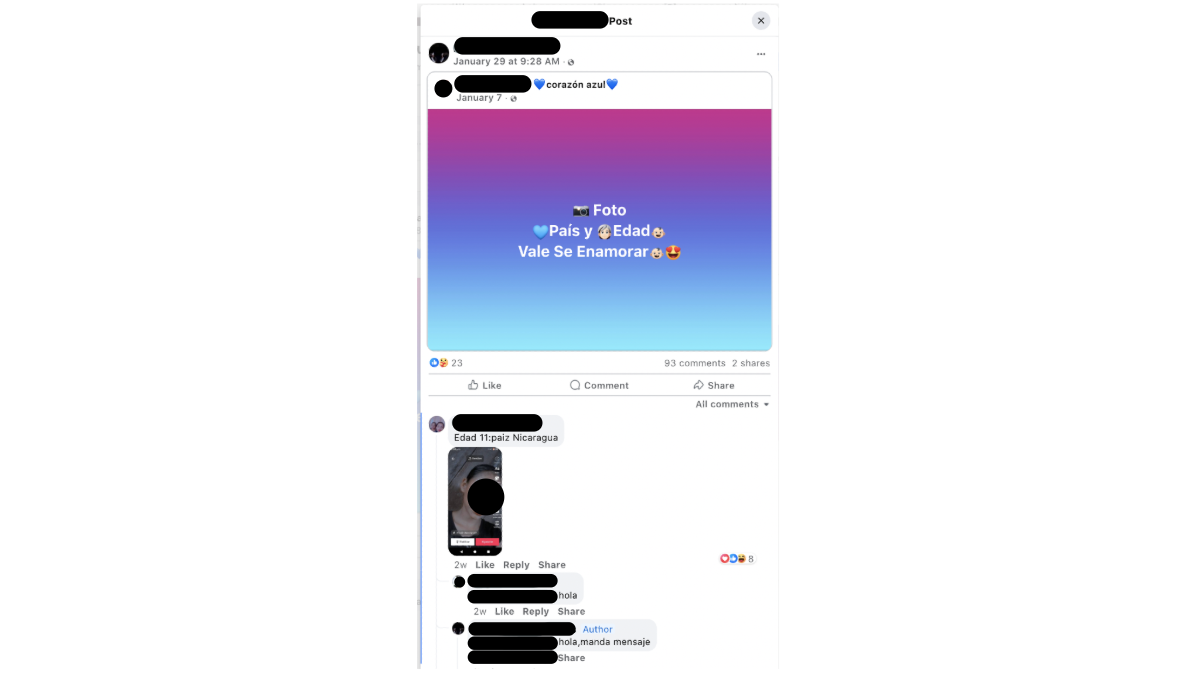

Even posts that do not explicitly favor replies from children by listing young ages confirm the widespread activity of very young teens and pre-teen children in this “True Beauty” fan group, which had become, by the time these exchanges were occurring, overwhelmingly full of sexual content (note, for instance, the “upcoming events” populating the sidebar seen in the screenshot below). In the following case, because the poster asked for the respondents’ home country, we can further assess the geographic origins of the children engaging with this content.

A post in a “True Beauty” fan group on Facebook.

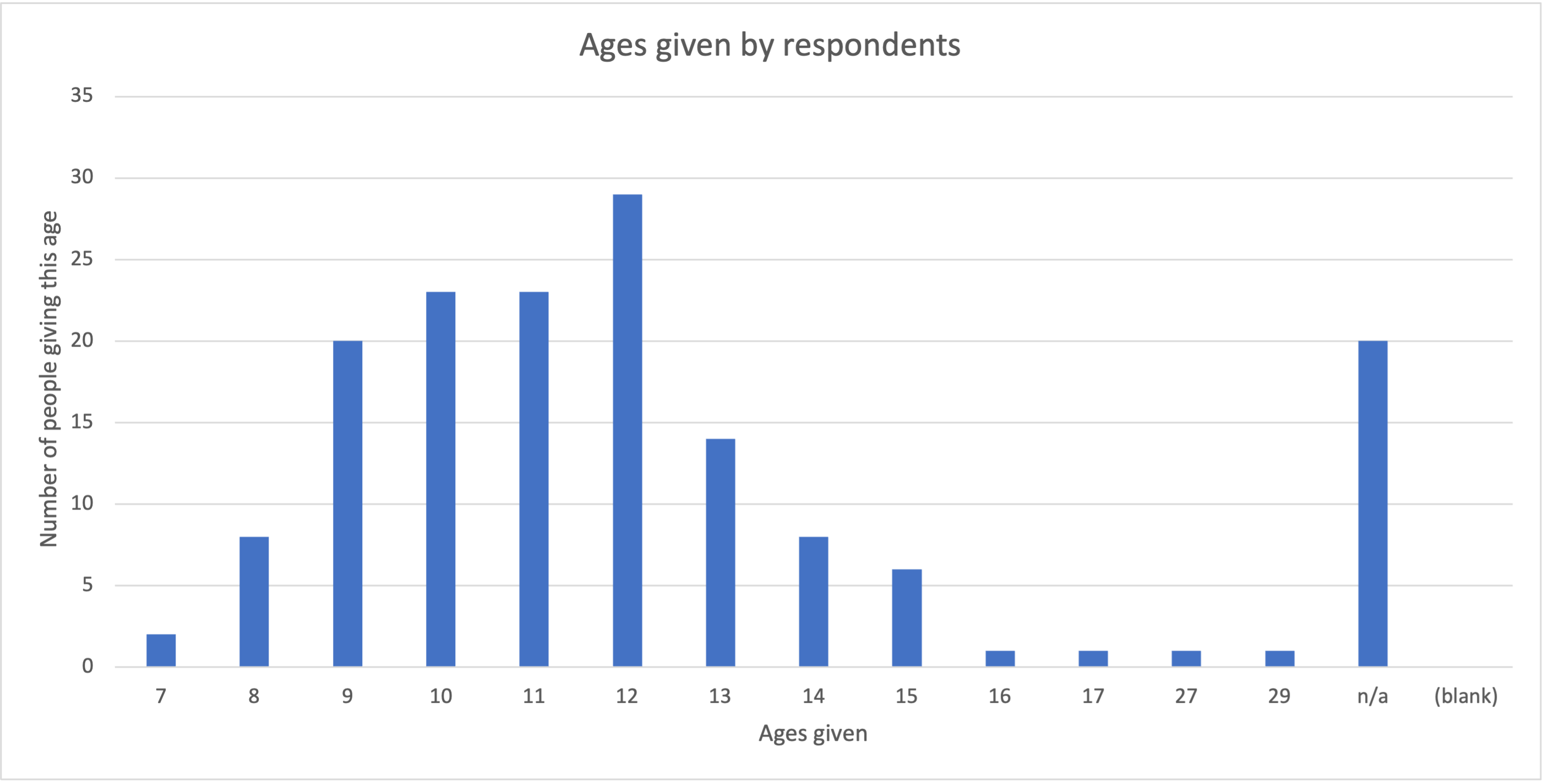

The above post asked participants to post photos, saying: “Photo. Age. Country. It’s okay to fall in love.” It generated 165 responses, of which 154 specified an age. Of these, one-fifth identified as 12 or younger. Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador (in descending order) had largest numbers of respondents overall, and likewise the largest numbers of accounts identifying as pre-teen children responding.

Number of accounts identifying as children 12 or younger from each country: Venezuela (7), Mexico (6), Colombia (4), Peru (3), Ecuador (3), Republica Dominicana (1), Bolivia (1), Argentina (1), unspecified (3).

Twenty-nine accounts indicating they were children aged 12 or younger responded to this post, most of them also uploading photos.

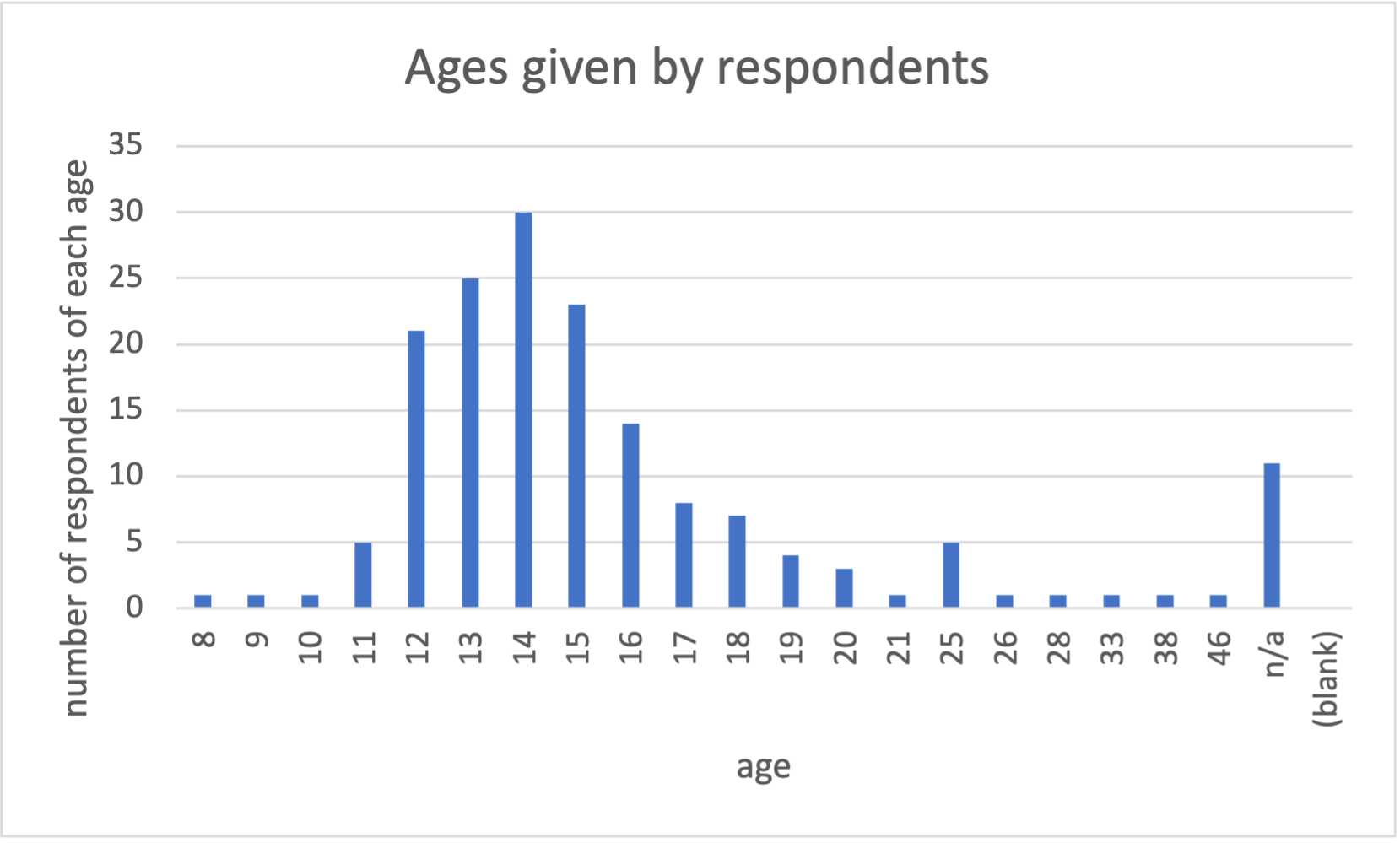

Other Spanish-language fan groups beset by sexualized engagement content show a similar blend of origins and ages. For instance, a different Spanish-language “True Beauty” fan group, with 135,000 members, seems somewhat less active, with recent posts comprising a mix of links to handmade videos whose stills suggest imminent sexual assault, celebrity sex videos, and Korean youth celebrity content. (I have previously described the apparent cycle through which swarming by accounts pushing ever more explicit sexual content seems to ultimately drive the bulk of users, their targets, to decrease engagement with the page.) In this group, a similar post asking for “Photo, age, country, and I’ll rate you from 1 to 10; It’s ok to fall in love” generated a very similar age and geographic portrait of participants. A third of the respondents who gave their age indicated they were from Mexico, with Venezuela and Colombia next, and smaller numbers from elsewhere across Latin America. The median age given was 13, and 30% of respondents indicated they were 12 or under.

Number of accounts identifying as children 12 and younger from each country: Mexico (9), Colombia (3), Venezuela (3), Peru (2), Spain (1), Honduras (1), unspecified (3).

Note that the frequency of similar posts in this and similar groups suggests that public Facebook groups are currently a mass-scale repository of photographs and personal identifying information of minors in general and of children under the age of 13 specifically. Some posts ask explicitly for physically revealing photos. For instance, the below meme, appearing multiple times across various groups, shows a girl taking a selfie in a mirror, with text asking respondents to reply with a “Photo in a little skirt or shorts, and age.”

An image in a Facebook group asks girls to share physically revealing photos.

How common are youth-oriented groups full of posts seeking sexualized engagement from children or offering prizes to children for sharing contact information and establishing private messaging connections? Only Meta would be able to assess fully what portion of its Spanish-language groups match this profile. As an external observer with access to public groups, I can only say they are numerous and large. Other fan groups I found that appear to be large-scale targets for sexualized child solicitation include Puerto Rican rapper Young Miko, Mexican singer and influencer Kimberly Loaiza, and Phoenix, Arizona-born teen sensation Xavi, whose Mexican regional-style music is breaking through to international charts.

The fact that both Young Miko and Xavi are US citizens offers an important reminder of the border-crossing nature of celebrity fandom, an essential growth driver for stars and social media platforms alike in today’s digital distribution world.

An example of the sexualizing content that has flooded into the groups I am describing is the below post from a Xavi fan group. It is a cartoon, in manga visual style, showing an adult male, unclothed at least from the waist up, reaching from behind to hold a young girl in an apparent sexual act. Her head is surrounded by hearts, and her mouth hangs open. The text reads: “If you like older men, say hello.”

A post from a Xavi fan group on Facebook.

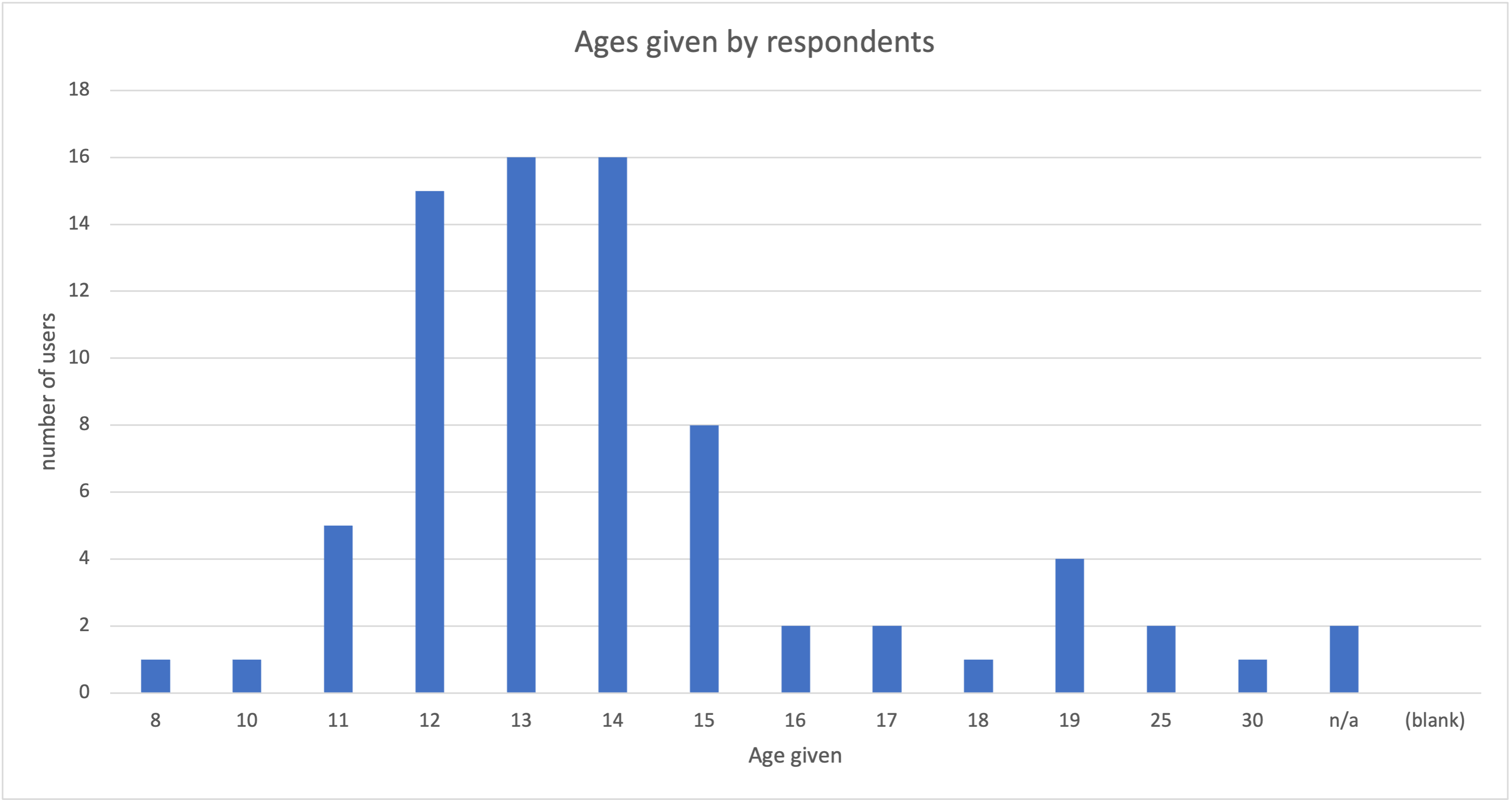

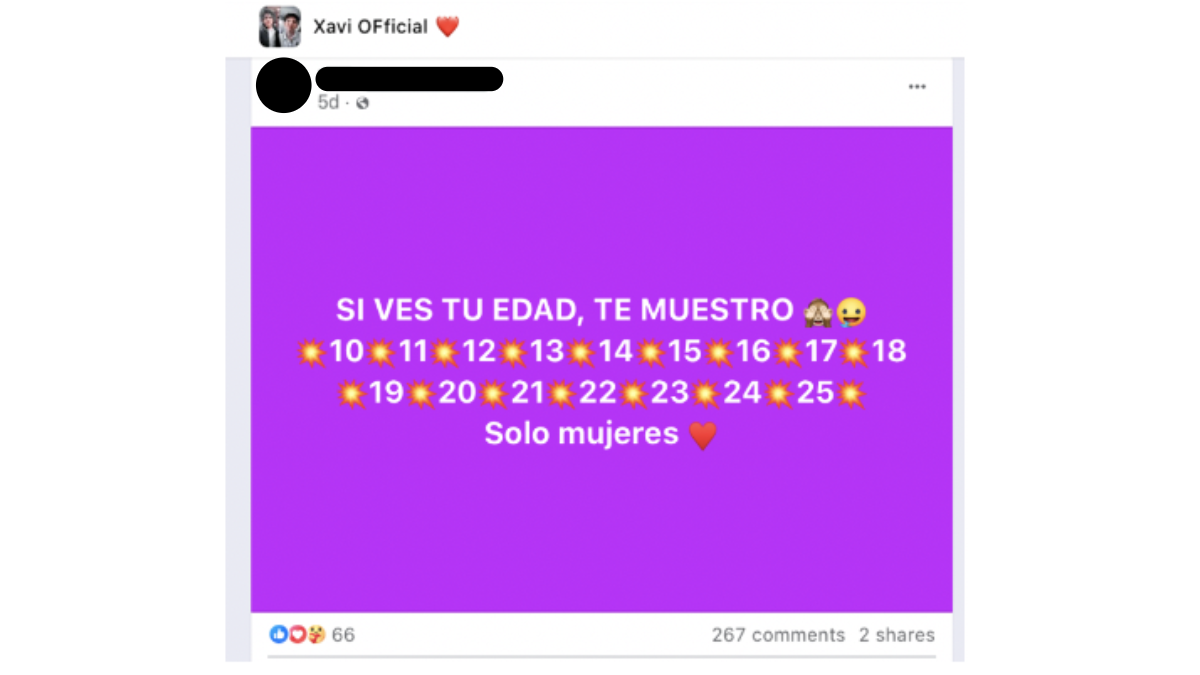

The age profile of child participants in Xavi fan groups seems similar to that of the “True Beauty” fan groups described above. For instance, the following post is from another Xavi fan group and reads, “If you see your age, I’ll show you [eyes-covered emoji; salivating emoji]: 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25. Only women.”

A post from another Xavi fan group on Facebook.

In this case, 42% of responses came from users self-identifying as 10, 11, or 12 years old.

Many Xavi fan groups on Facebook do not have a significant amount of sexualized child solicitation content. However, the five Xavi groups I found that were suffused with such content comprised a significant presence even on their own, summing over 860,000 members in total as of Spring 2024.

The capture of Los Picus fan groups by child-endangering users seems even more extensive. I described at length in a previous article the groups built around this Mexican child hip-hop trio: the three brothers, ages 8, 10, and 12, and the 10-yr-old’s and 12-yr-old’s “girlfriends,” Paula and Allison. When I wrote in Tech Policy Press in January 2024, I identified twenty Picus-associated fan groups with a preponderance of child sexualizing or sexualized solicitation content. As I continued to follow the trail of algorithmically recommended “related groups” over the following weeks, I found more. Four months later, the total was thirty-four groups with over 930,000 combined members.

The Los Picus fan groups beset by predatory content seem to trend even younger, in terms of the ages given by users engaging with age-trawling posts, than the True Beauty, Young Miko, and Xavi fan groups described above. For instance, 153 Tony Piculin fan group users responded to a post reading “Photo Country Age. Okay [to] Fall In Love.” Fully 65% of respondents were 12 or younger. Surrounding the post were links to adult pornography groups, an apparent CSAM video involving a young teen in a school uniform (I reported it, as I did on numerous occasions when I encountered similar content), and posts claiming to be from Tony Piculin (one of the brothers) asking for girls to perform dares.

A post reading “Photo Country Age. Okay [to] Fall In Love.”

In another fan group, built around Tony Piculin’s girlfriend Paula, someone using the username “Tony Pi” posted, “Hello princesses how are you, put your age country to add you.” Several respondents clearly believed they were, in fact, communicating with child star Tony Piculin himself: “Tony give me your number Tony” wrote one. 81% of respondents gave their ages 12 or under; 10 was the most common age. The screenshot below includes the post that appeared adjacent to this one in my feed: a cartoon that seems to show a boy having sex with a girl from behind, along with the caption “say hello and I’ll show it to you in priv[ate].”

Posts in a Facebook fan group built around Tony Piculin’s girlfriend Paula.

Number of accounts identifying as children 12 and younger from each country: Colombia (10), Venezuela (9), Peru (8), Mexico (6), Ecuador (3), Guatemala (2), Santiago [Chile?] (1), USA (1), Cuba (1), Argentina (1) Uruguay (1), Nicaragua (1) El Salvador (1), unspecified (10).

Pre-teen respondents to this post came from various countries, with Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, and Mexico topping the list.

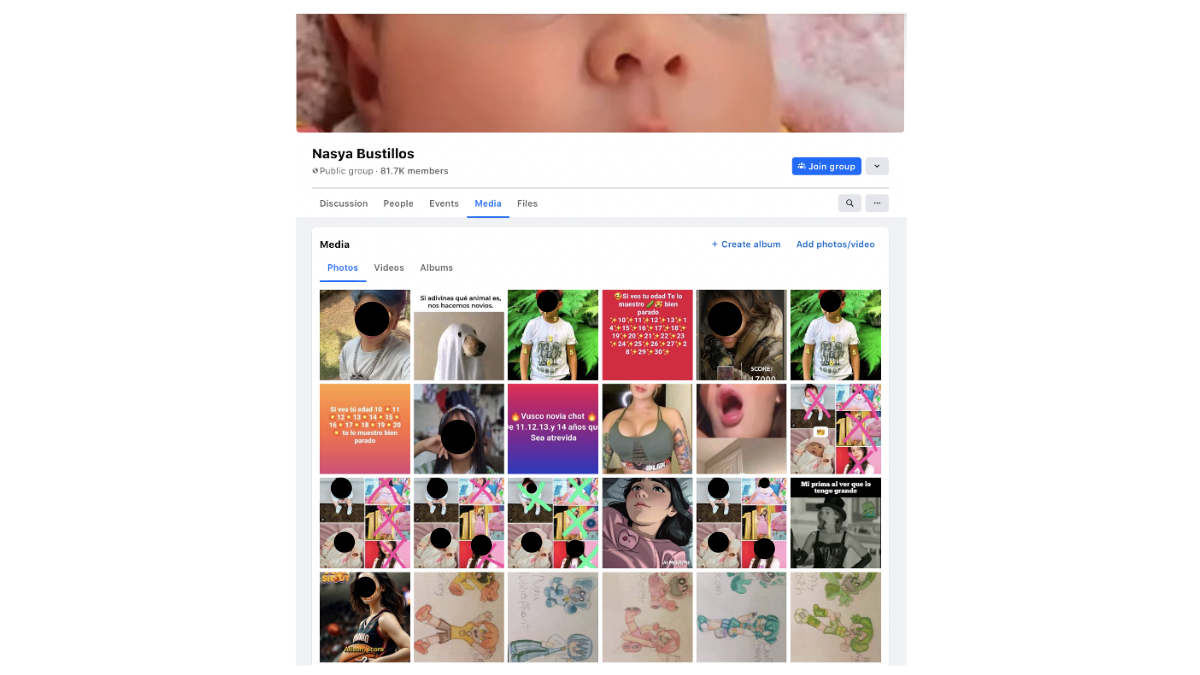

One final cluster of child-endangering fan groups merits special discussion. “Team Karmas” is an influencer “family” built around Mexican former fitness coach Mau McMahon; his partner, model Karla Bustillos; her young niece Daniela; Daniela’s “boyfriend” Spy; and now Karla and Mau’s infant daughter Nasya. McMahon has 25.9 million followers on YouTube, 9.7 million on TikTok, and 1.2 million on Instagram. Karla has 40 million followers on YouTube, 31 million on TikTok, and 3.9 million on Instagram. The content they produce and circulate via these platforms offers a particularly clear example of how legitimate influencer content can be highly synergistic with predators’ goals of normalizing or gamifying child sexual behavior and sexualized age play. Examples include a long “contest” in which Mau and Karla dare Daniela and Spy to see how long they can hold a kiss on various parts of the other’s body while performing dares (this had 14 million views at the time I saw it, and has now been removed for violating YouTube guidelines); Karla and Mau switch places with Daniela and Spy; Daniela and Spy are married for the night; everyone tastes Karla’s breast milk.

I found seven Facebook groups framed as fan groups for Karen, Daniela, or Nasya Bustillos that are pervaded by sexualized child engagement content. As with all the other fandoms discussed, there are other Facebook fan groups for Team Karmas members that do not (yet?) seem to have become targets for predators. But the ones that are are not negligible. The seven Karen/Nasya groups found that contain child-endangering content together have over 290,000 members.

Here is a screenshot of “recent media” in one such group, showing a familiar blend of age-trawling posts, Los Picus content, pastel cartoons, and sexual memes (for instance, of a shocked woman with the caption “my female cousin when she sees how big mine is”).

A screenshot of “recent media” a Nasya Bustillos fan group on Facebook.

Systematically, participants in Team Karmas fan groups seem significantly younger than in the other groups profiled: many identify as elementary school-age children and relatively few as teenagers.

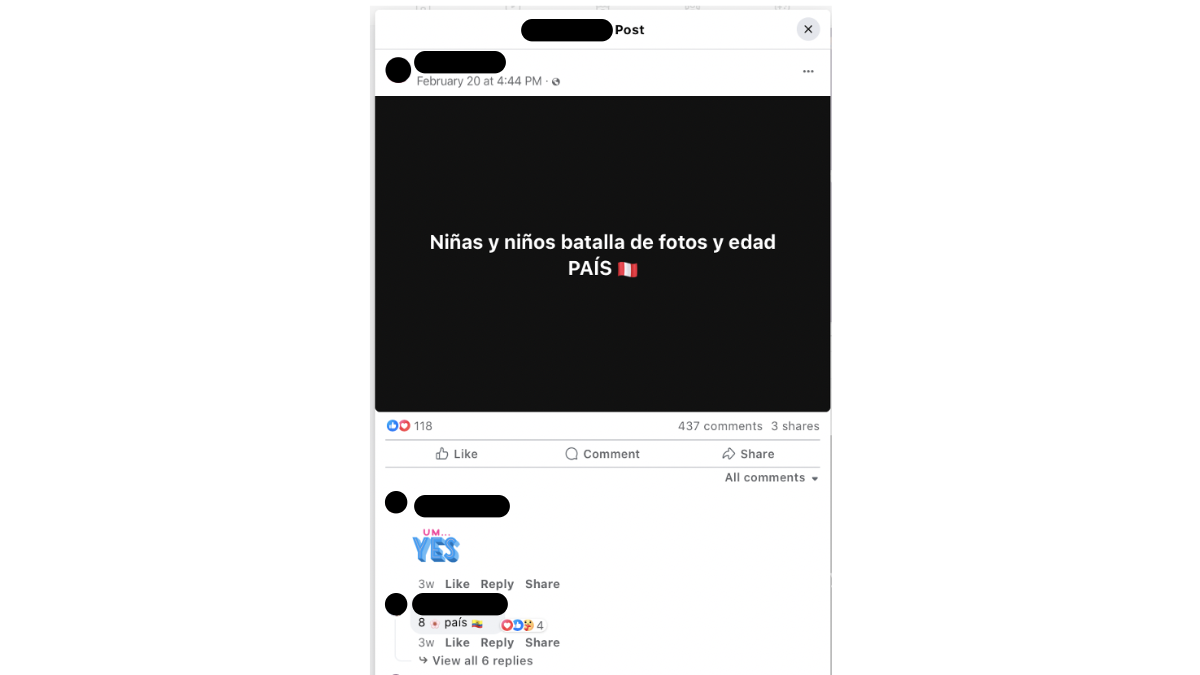

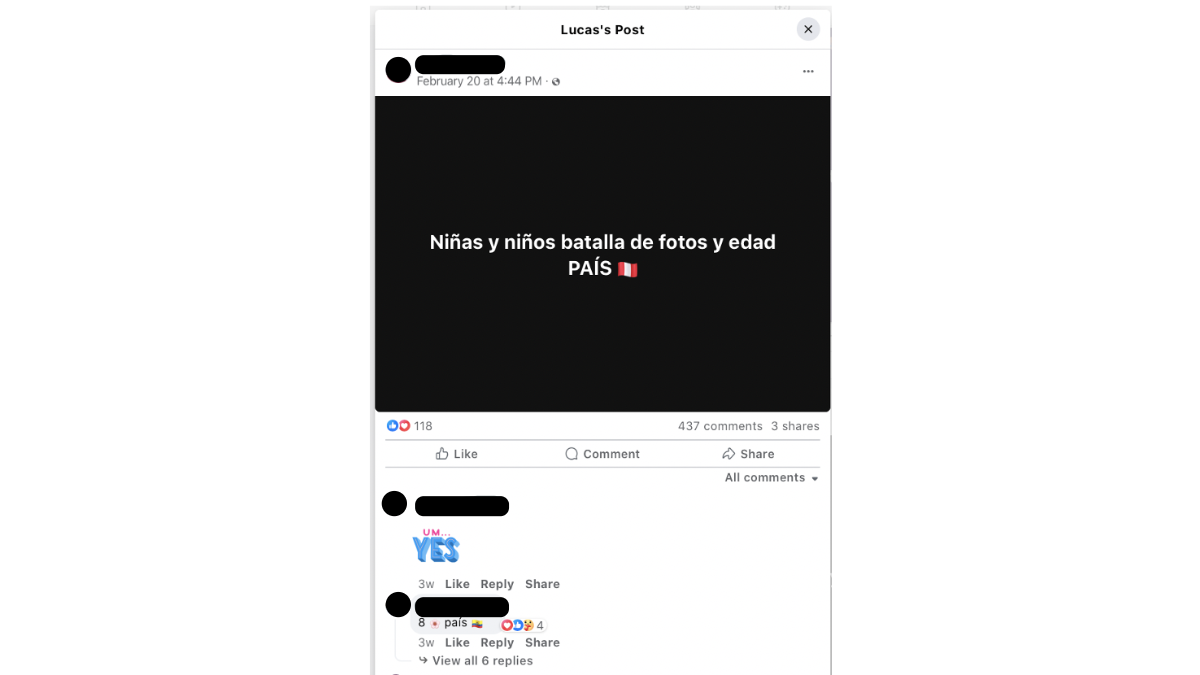

A post in a Team Karmas fan group on Facebook.

For instance, the above post (“Boys and girls: Battle of photos, age and country”) drew responses from 137 respondents who indicated their age; among them, the median age was 11. Replies to this post alone included over 100 self-described children under 13.

Number of accounts identifying as children 12 and younger from each country: Mexico (23), Peru (19), Venezuela (16), Colombia (13), Ecuador (12), Argentina (5), Honduras (3), USA (2), Cuba (1), Germany (1), unspecified (10).

The geographic spread of the apparent children engaging with this fan group, which is centered on the mother-infant (Karla-Nasya) pair, comes from the same range of countries we have seen previously represented.

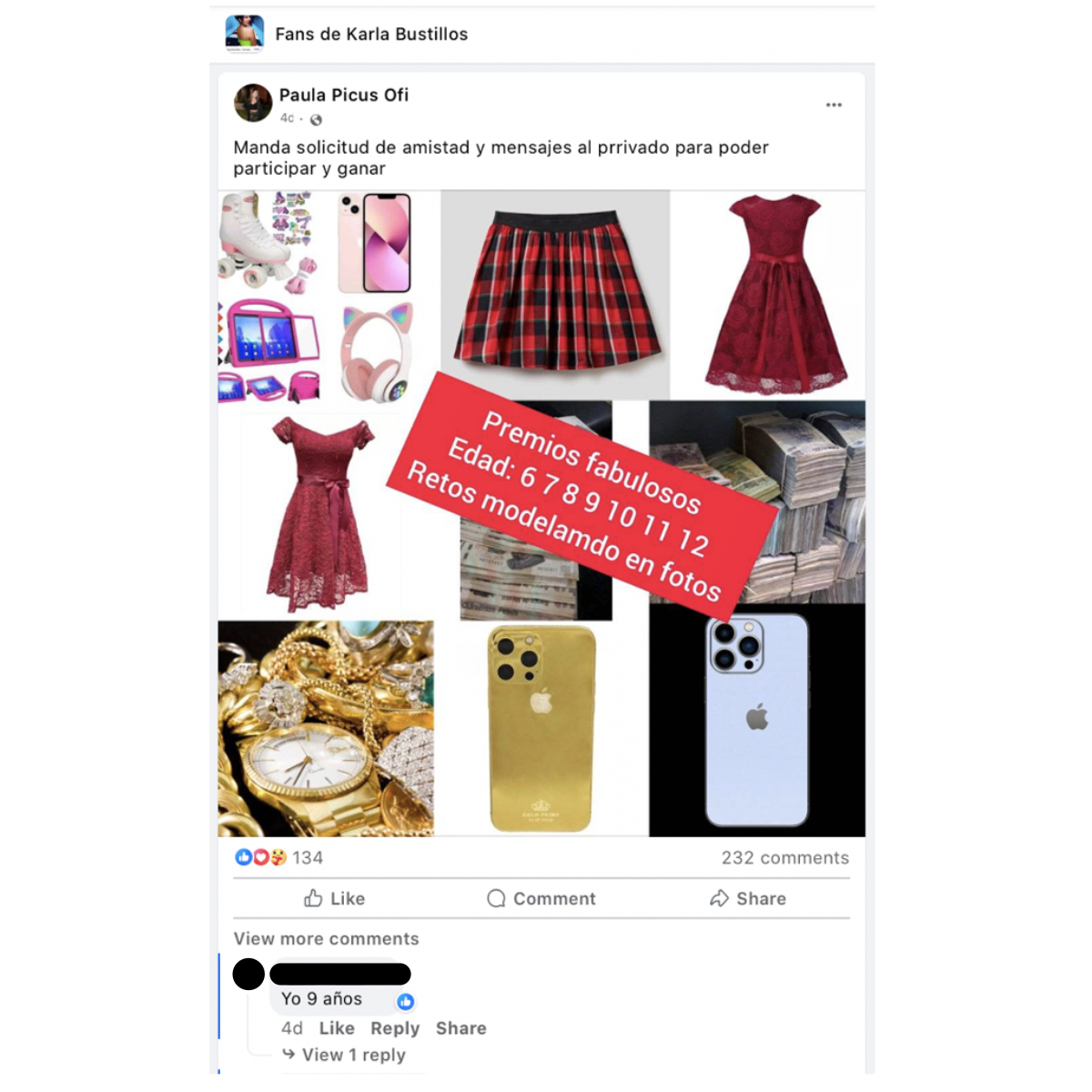

As in the Los Picus groups, posts here frequently combine multiple child-alluring components that would seem to violate Facebook’s guidelines: in particular, impersonation of celebrities and promises of prizes, including smartphones, cash, jewelry, and toys. For instance, the following post, from a Karla fan group, falsely purports to be from Picus-linked influencer Paula Cacho. The text reads: “Send a friend request and private messages to participate and win. Fabulous prizes, age: 6 7 8 9 10 11 12, Do challenges modeling in photos.”

A post from a Karla fan group falsely purports to be from Picus-linked influencer Paula Cacho.

In this particular case, the replies offer a public glimpse into what happens out of view when accounts identifying as children respond to a post such as this and follow the original poster’s guidance to add them as “friend” and thus enable private messaging to begin. Far down among the 232 comments on this post, one reply states: “Look don’t let yourself be fooled by these publications, it’s just little girls who are tricked, look at the messages that were sent to my seven-year-old daughter.”

This poster included screenshots of direct message interactions with the same “Paula Picus Ofi” account that had initiated this post, with its offer of prizes for modeling.

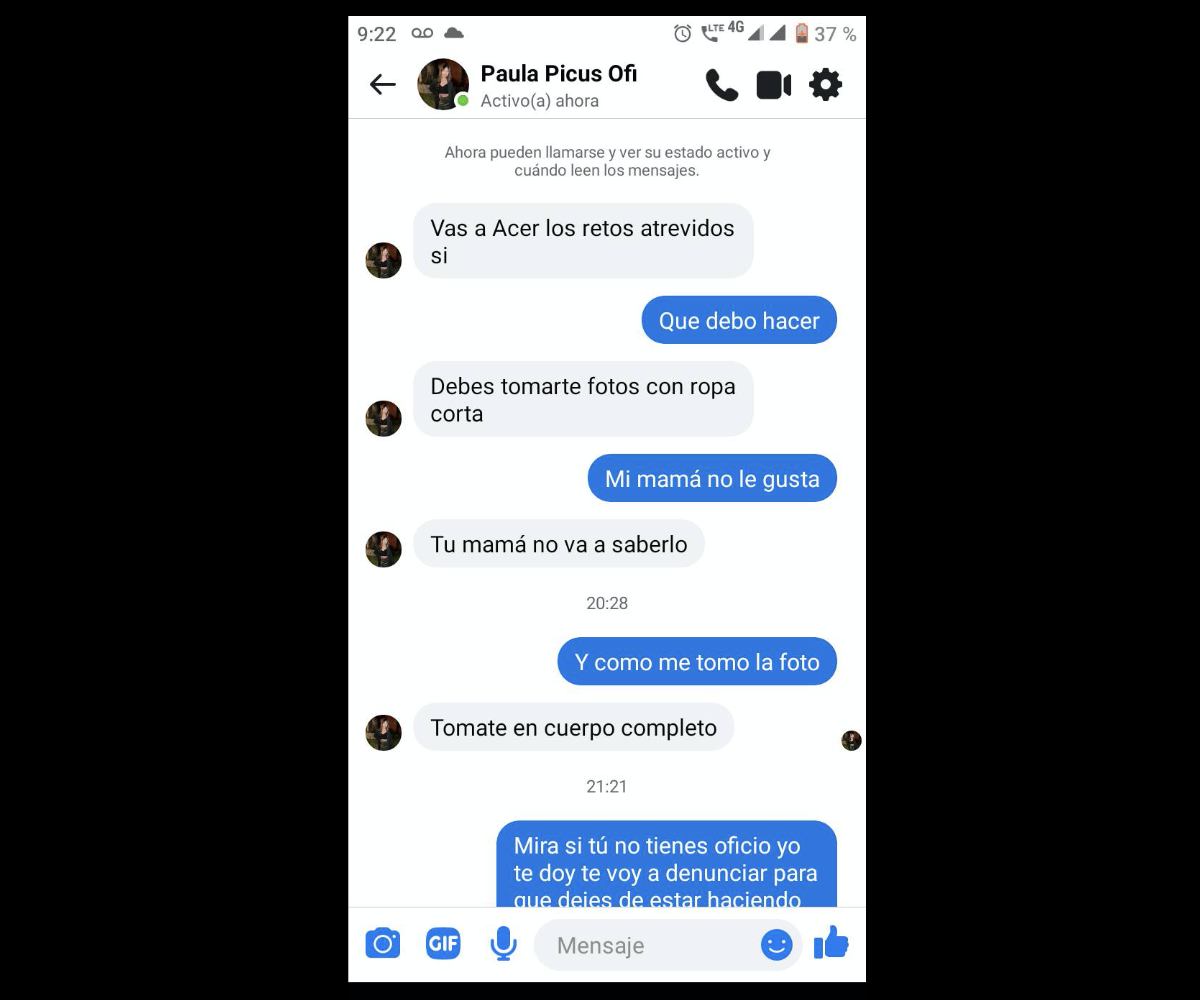

Screenshots of direct message interactions with a “Paula Picus Ofi” account posted in a Facebook group.

Here is the full translation:

“You are going to do the daring challenges yes”

“What do I do?”

“Take pictures of yourself in short clothing.”

“My mom doesn’t like me to.”

“Your mom is not going to know.”

“And how should I take the photo”

“Take it full body”

[At this point the mother apparently regains her phone from her daughter who had been texting.]

“Look if you don’t have a proper job to do I am going to denounce you so that you stop doing”

[screenshot cuts off]

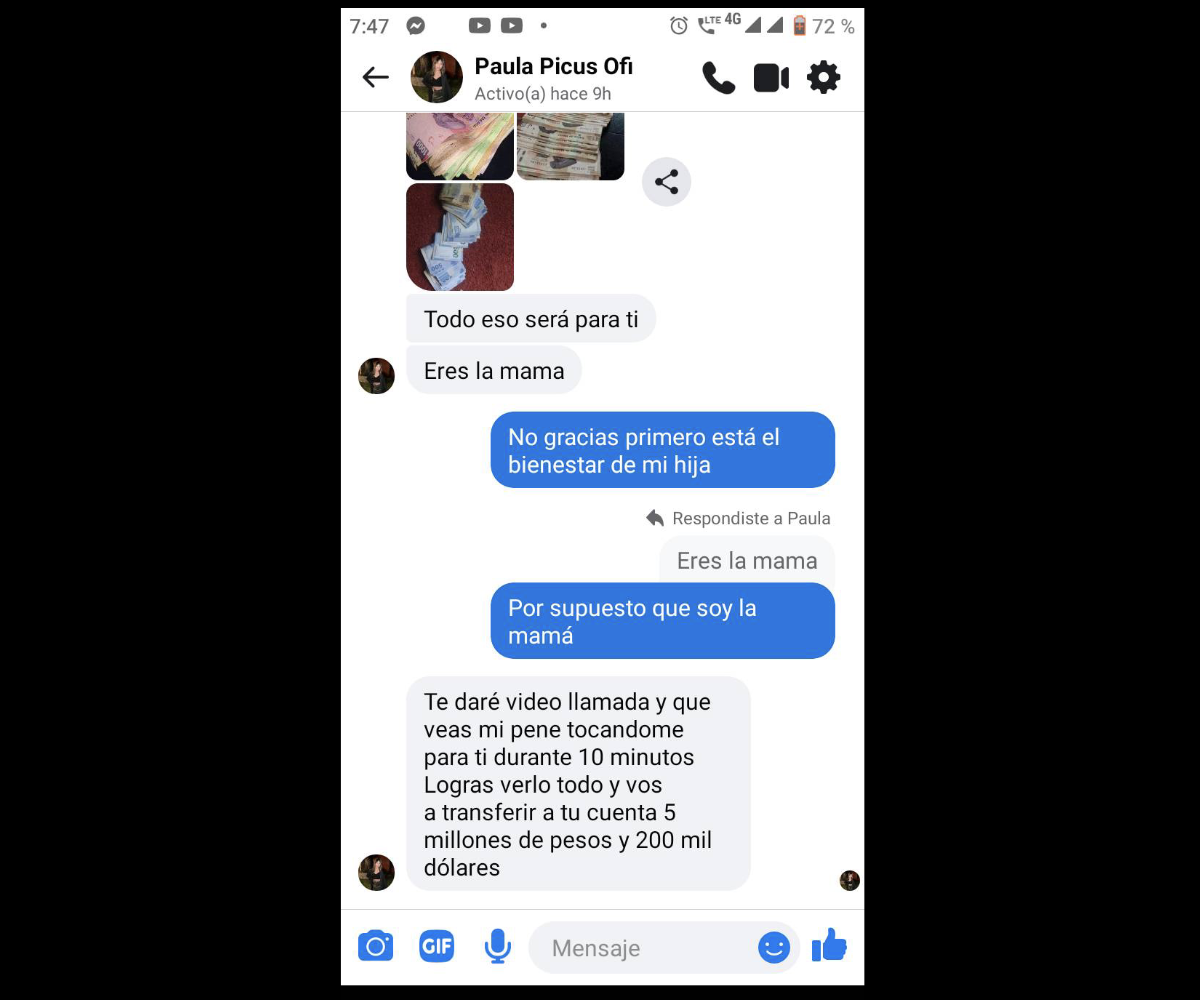

The second screenshot, shared as a reply by the same user, begins with photographs sent by “Paula” of stacks of cash.

Screenshots of direct message interactions with a “Paula Picus Ofi” account posted in a Facebook group.

The exchange reads:

“All of this will be for you. You are the mother.”

“No thank you the wellbeing of my daughter comes first.”

“Of course I’m her mom”

“I will videocall you and you will watch me touching my penis for you for 10 minutes. If you manage to watch the whole thing I will transfer to your account 5 million pesos and 200,000 dollars.”

This same “Paula Picus Ofi” account posted similar content in multiple fan groups. It seemed particularly urgent to try to get action taken. I reported the post through Facebook’s automated system as “involves a child” and abusive, which leads one through a standard screen listing things that Facebook “doesn’t allow,” including content that “solicits sexual activities or sexual content from” children; expressions of sexual interest in children, “content that exploits children by showing them sexualized content,” or more. To any human reader it would be obvious that this post epitomizes exactly that (as does so much else of the content described and reproduced above). Yet Facebook’s automated filters are clearly not set to capture relevant cues. The post was not taken down.

Today’s celebrities use social media’s ubiquity and immediacy to forge intensely emotional (and profitable) parasocial relationships with young fans. Posts impersonating these beloved influencers seem to be particularly compelling to the youngest of users. For instance, the below post, from a baby Nasya fan group, reads: “I am looking for girls to model with Karla and Nasya. Age: 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12.” Two hundred and twenty-one respondents who identified as 12 or younger eagerly replied, asking to be contacted.

An image shared in a "baby Nasya" fan group on Facebook.

In the replies visible in the screenshot above, one respondent gives her name saying “I am seven years old seven.” Meanwhile a different respondent has written “Girls don’t believe it it’s false, they said the same to me and [then] told me to send them photos without clothes on.”

The back-and-forth as the replies unfold is wrenching, as child after child shows the intensity of their emotional connection to Karla, who is clearly so important to them and with whom they believe they are communicating directly.

“I can I’m ten years old and I am your first fan, where do you live?”

“I am nine and I’ve been your fan since you started to put videos on youtube.”

“Meeeeeee I am 8 I love you Karla.”

“I am ten but I’m small is that okay?”

“Hello my name is [gives email address] and I am 11 take good care of Nasya.”

Meanwhile, a few other users keep warning of deception and spelling out what they say has happened to them in replies like: “This is a lie, he told me he was going to send a picture naked.” The warnings seem to go entirely unread or unheeded.

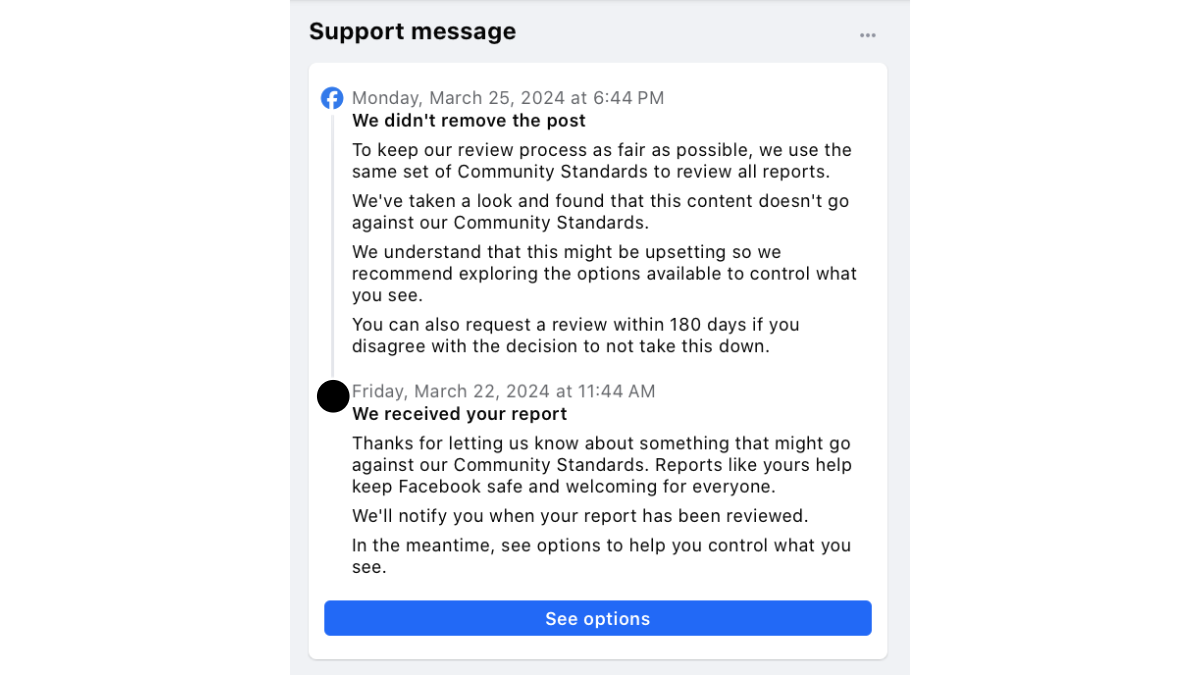

On March 22, 2024, I reported this post through Facebook’s reporting system as “involving a child” and violating platform rules. Three days later, the reply came back: “This content doesn’t go against our Community Standards.”

A Facebook support message following a reported post.

When I first reported it, this post had 500 replies. After I received the notification that it would not be removed, I checked back. It had 850.

Conclusions

Here is what we can conclude about the risks to Latin America’s children on Facebook. Given all the preceding, it seems a reasonable hypothesis that any Spanish-language Facebook group with significant numbers of teen members also has significant numbers of underage (pre-teen) child members—and is at risk of having significant numbers of adults join, seeking to prey on them. The “legitimate” use case or value proposition intended to bring the next generation of Latin American youth onto Facebook seemingly overlaps almost entirely with the criminogenic use case.

In addition to its automated systems, Facebook’s guardrails to ensure child safety are, firstly, that kids under 13 are not allowed on at all; secondly, that adult strangers cannot DM minors; and thirdly, that reporting tools allow users to police their own spaces. The patterns described above suggest how flimsy, in practice, each of these guardrails seems to be. The cumbersome reporting tools frequently do not yield takedowns even when what appears to be violative content is reported; both external surveys and self-descriptions online suggest children under 13 openly form a significant part of Facebook’s established user base; and successful social engineering by predators to bypass the limit on direct messaging is constantly in on display, with adult posters offering fake prizes, impersonating celebrities, and sharing sexualized age-trawling posts: and telling children exactly how to click to add them as “friend.”

Indeed, Facebook could choose to take down by default posts in which the original poster replies to dozens of comments asking to be added: systematically, when that happens, it is a stranger seeking private access to users they could otherwise not contact. More fundamentally, Meta should have heeded the internal voices raising concerns over children’s targeting on their platforms long ago. And, concretely, Facebook should have taken more proactive steps to protect Spanish-speaking children before expanding in Latin America. Ironically, in this world region in particular, Facebook’s own initiative and subsidies played a key role in bringing so many households onto the internet in the first place.

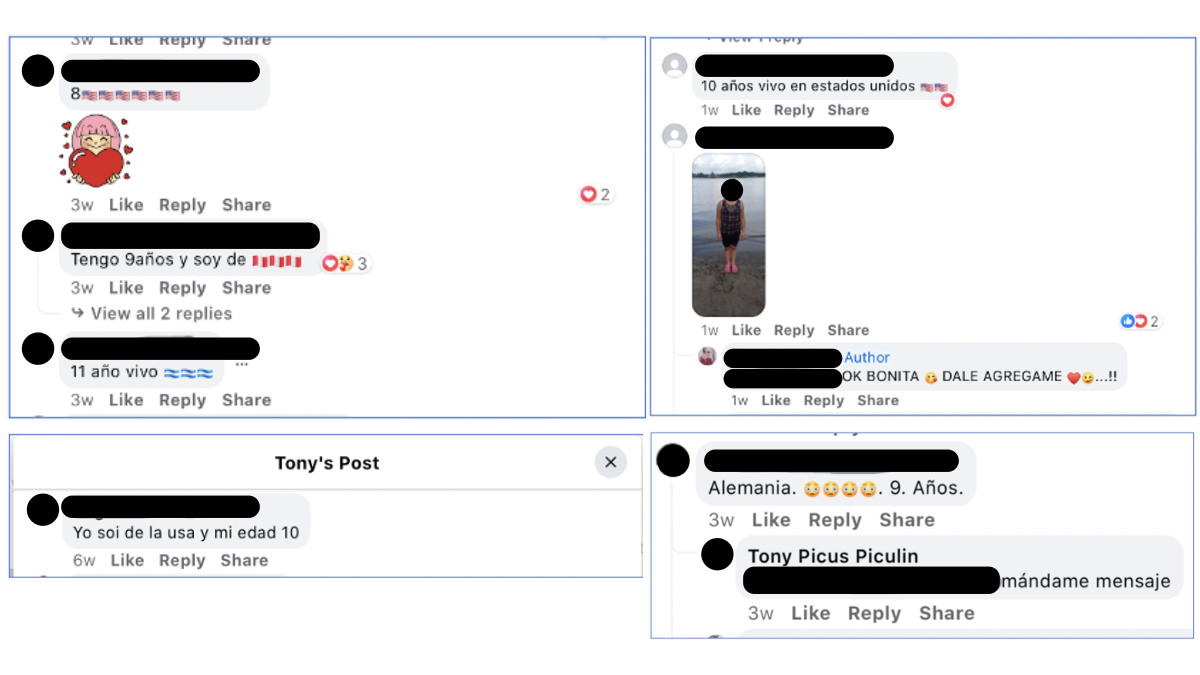

It is worth underlining that risks created by the apparent presence on Facebook of large numbers of Latin American children do not stay solely within the bounds of Latin America. Individuals replying to the name-country-photo request in the Baby Nasya fan group profiled above seem to include at least one user identifying as an 8-year-old from the US, one 10-year-old from the US, and one 9-year-old from Germany. In today’s world, fandoms and influencers’ reach do not remain walled off in one region. It would be surprising if some number of Spanish-speaking children in the US and Europe were not participating and facing risks of harm in these Facebook groups, and the traces captured in the screenshots below seem to confirm that they are.

Screenshots from Facebook groups where accounts indicate that they are children and name their ages.

Whether child-endangering interactions in de facto child-directed Spanish-language Facebook groups will attract the scrutiny of US and EU regulators is yet to be seen. To what extent legal authorities or child-protective agencies in Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Honduras, and other impacted nations may seek to exert pressure on Meta to conform to local legislation regarding children’s safety and privacy is, likewise, an open question. Meta says it reports all apparent instances of child sexual exploitation content to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which works with law enforcement in countries around the world, consistent with local laws.

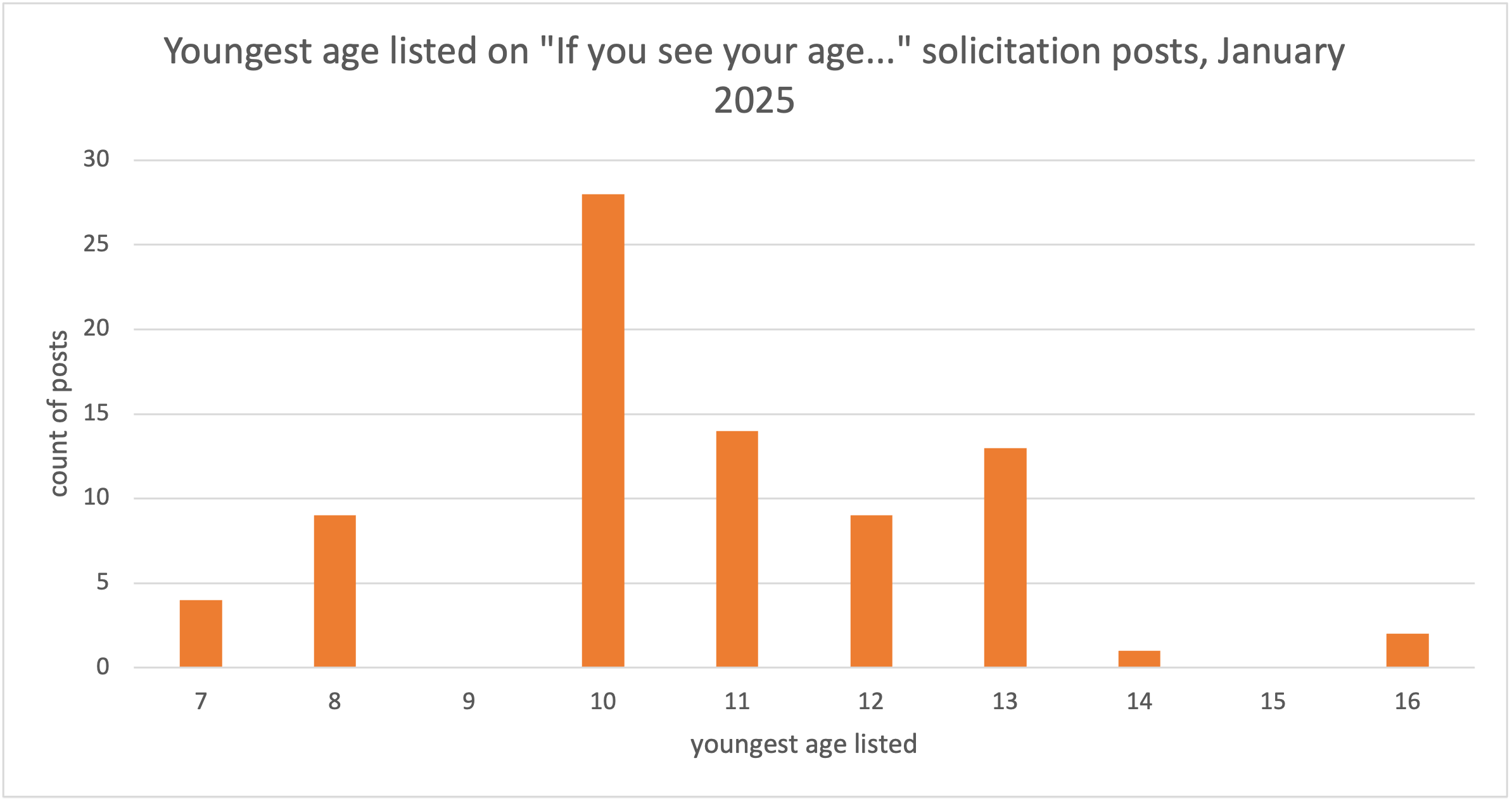

As a final note, the charts and graphs above are based on posts observed in Facebook groups in Spring 2024. Over the following months, individual groups grew or declined in dynamism, following the same pattern of apparent crowd-out by predatorial or spamming content I noted in my initial report last January. However, even as the specific foci of activity evolve, many tactics remain identical, so much so that it seems astonishing that no basic automated guardrails have been put in place to flag such content. For instance, a simple search for the phrase “si ves tu edad” in posts for the month of January 2025 returns 80 posts, many literally identical, all of them what I described in my January 2024 report as “age-trawling” posts: reading “If you see your age, I’ll show it to you”—sometimes with the addition of milk bottle emojis, referencing ejaculation—or “If you see your age, I’ll send something privately,” followed by a list of ages. In a shift from the pattern nine months earlier, BTS and other K-Pop fan groups outnumber Mexican pop star fan groups in this set. However, the open and explicit focus on soliciting engagement from pre-teen Facebook users remains unchanged. Of the 80 posts from January 2025, 96% begin their list of target ages with an age under 13. Posts beginning their list of desired ages for respondents with age 10 are the most common, while other posts begin with ages as young as 7 years old.

In the course of preparing this report, Tech Policy Press shared multiple examples and group URLs with Meta. Most of the material to which we provided links through this direct route was promptly removed. But new searches for similar material continue to yield results, and reporting similar groups and content through Facebook’s online reporting tools continued to fail to lead to immediate removal.

Authors