Invigorating the American Space Sector Requires Working With NASA, Not Against It

Janet Vertesi / Mar 4, 2025

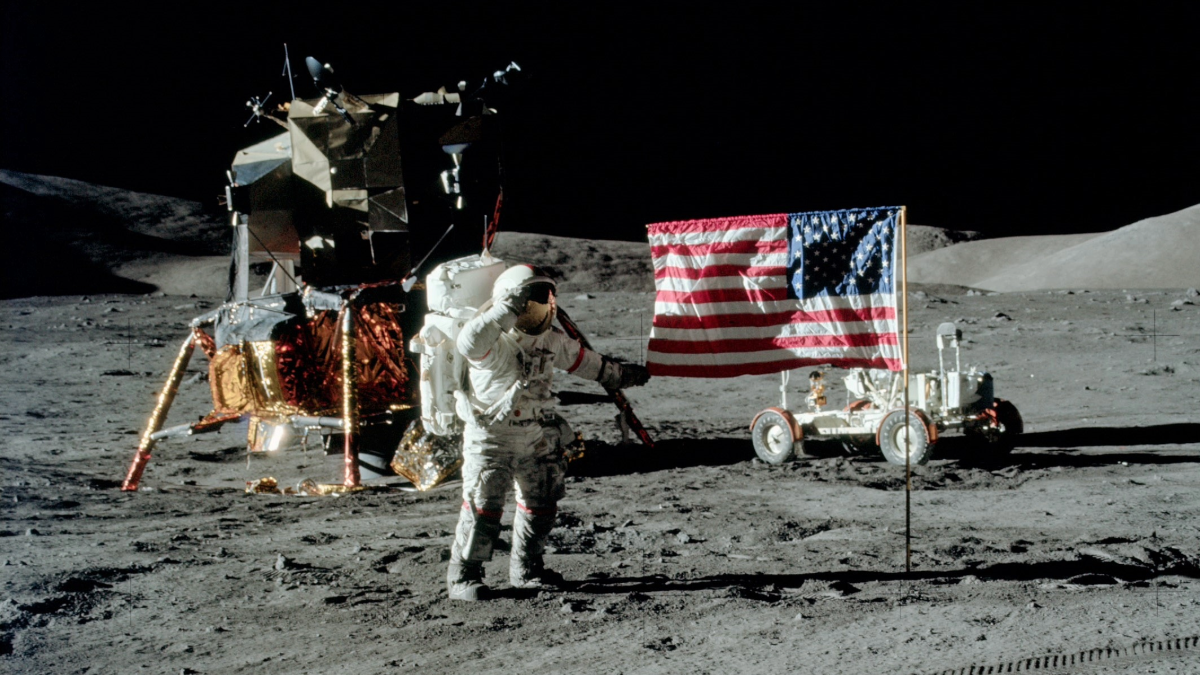

December 12, 1972—Eugene Cernan on the Moon during the Apollo 17 mission. Harrison Schmitt/NASA Wikimedia

The United States is witnessing the dissolution of multiple government science, health, and technology agencies in real time. At the top scientific and technological centers in the world, employees are being fired or furloughed, long-standing programs are being canned, or are teetering on the brink of collapse. The new administration promises that such cuts will restore American "greatness" and secure both savings and efficiencies. But as the history of the space program teaches us, when programs are cut to the bone, America loses much more than it gains.

When the band breaks up, the music stops

When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their historic steps on the moon in 1969, the United States was at a budgetary crossroads. Increasingly in debt to fund the war in Vietnam, President Richard Nixon declared cuts to NASA and tighter congressional oversight over ever shrinking budgets. NASA's budget crashed: from $67 billion to between $20-30 billion. Despite Apollo’s astonishing success, its final mission flew in 1972. The project was shuttered.

Apollo was not just de-funded: it was de-institutionalized. Its high-class engineering corps was dispersed under the premise that they would take their knowledge with them to a burgeoning private space sector. Some of these engineers went to partnering companies like Lockheed, Martin Marietta, or Boeing. But the intricate how-to’s essential for planning subsequent lunar landings did not spread: it withered and died. In the intervening time, America quite literally forgot how to get to the moon.

We are fond of saying of technological breakthroughs that once the genie is out of the bottle, it is impossible to put it back in. Not so. It is possible, even easy, to systematically forget or lose entire swaths of technical or scientific prowess—if you dismantle the human teams and institutions responsible for them.

As a social scientist who has worked with NASA and other technical groups for two decades, I can explain why this is. The know-how necessary to achieve such complex feats as lunar or Martian landings is not something that single people hold in their heads. One cannot even learn it or reconstruct it from documents, reports, or papers. Knowledge of this kind of complexity is a group phenomenon. Expert teams of people who work together over a long period of time develop the skills, know-how, and the "secret sauce" necessary to get the work done. These teams pass that intangible know-how along to the next generation of engineers: vital, hard-won information transmitted through training, culture, and mentorship to ensure that the wheel does not need reinventing down the line.

This is why we create and sustain organizations, companies, or national agencies. It’s not just about fostering innovation, but about the need to support, safeguard, and sustain precious team know-how. Of course, institutions that were once innovative can get stuck in a rut, and people may reinvent the wheel elsewhere. But once the band breaks up, its secret sauce is lost. When America next turned its sights to the moon in the twenty-teens, experts began reverse-engineering museum parts to reconstruct the lost secrets of the 1960's.

The misleading allure of the Silicon Valley approach

Now, Apollo’s loss is poised to repeat. A new space sector flush with investor dollars and venture capital, the towering promises and deep pockets of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have captivated the attention of the public and lawmakers alike. Promising the moon—or Mars—supporters of New Space presume NASA's lead is easy to follow. They describe its spending as wasteful or inexpert. Many believe that there are faster and cheaper ways to maintain American dominance in space and that NASA’s embarrassing overages can be corrected with good business sense and private sector efficiency.

Silicon Valley leaders exhort their followers to "fake it til you make it," "move fast and break things," or be "embarrassed" by their first launches in order to achieve the scale investors dream of. Many a software company has become a unicorn without a fully-functional or even a profitable product. But you cannot fake your way into space. Near Earth Orbit is a challenge, yet deep space is utterly unforgiving. Mars is especially hostile, with its unearthly atmosphere making for perilous descent and landing and the planet's lack of shielding from harsh radiation. Small wonder Mars is also known as a “spacecraft graveyard,” littered with dozens of failed attempts undertaken by the best minds in the world in Russia, China, Europe, Japan, and the United States. Only two institutions on our planet have successfully landed anything at all on Mars: the Communist Party of China (once) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (nine times).

NASA makes it look easy, but no amount of bravura can make up for the group know-how necessary to achieve this feat—perfectly, on the first try, as the world watches in real time. Cut costs and cut corners, NASA learned the hard way, and you end up paying for crashed spacecraft. Experiments with low-cost missions to Mars in the 1990s lost $290 million worth of spacecraft parts and inspired the local saying: “Faster, Better, Cheaper—pick two."

Cheaper is the sticking point. Although NASA is beloved across the US and admired around the world for its technical feats, the agency seems incapable of staying on budget. As someone who has studied NASA missions up close for years, this is not a question of “grift," greed, or dishonesty. To the contrary, NASA teams are subject to extreme levels of cost-consciousness and austerity that would be unrecognizable in any business enterprise. Silicon Valley startup perks are legendary, from unlimited snack stations with free-trade coffees and five-star chefs, gyms, and laundry services, all buffered by venture capital or investors. At NASA, you must bring your own mug and your own coffee.

Not only is NASA's annual funding severely strained, it's unpredictable. Each year, Congressional cuts, new priorities, shutdowns, and furloughs cut space projects off from funds precisely when they need them the most, disrupting vital tech development and wreaking havoc on teams' best efforts to stay on time and under budget. Missions partner with a sprawling network of contractors in an effort to stabilize costs, risk, and political will. But this dilutes instead of preserves or distributes hard-won technical expertise, and costs balloon amid attempts to coordinate among so many different groups. The James Webb Space Telescope, for instance, involved several hundred contracting units and was delivered ten years late and $10 billion over budget.

Institutions are worth protecting

So what is a cost-cutter to do when faced with a problem like NASA? The challenge is both to retain technical expertise as a national treasure and to keep line items on track. First, we must resist massive slashes to NASA personnel and already anemic budgets when funding is already on life-support. Excessive, random cuts, mass layoffs, and fully canceled programs will not induce a strong and vibrant space sector by dispersing NASA experts to the four winds. Instead of taking their secret sauce with them to inspire private sector breakthroughs, breaking up the band destroys the group know-how essential to retaining American pre-eminence in spaceflight. History teaches us that this genie, once out of the bottle, does not spread—it evaporates instead.

This gutting is already underway thanks to decades of cost-saving efforts. Many NASA centers already employ short-term contract workers instead of civil servants for technical tasks. Rotating workforces may save money in the short term, but they undermine the development and preservation of team know-how, reducing the return on investment in the long term and excising technical expertise from NASA centers of excellence. NASA's administration and the US government must, therefore, keep the preservation of team knowledge—the hard-won and expensively-acquired "secret sauce"—front and center in any next steps.

Second, to ensure robust knowledge transfer to and throughout the private sector, the agency must invest in small scale, close partnerships between NASA centers and private companies. Tight-knit, one-to-one collaborations that pair a NASA center and a private spaceflight company under an intensive working arrangement have achieved both cost savings and innovation in the past, research shows. This keeps coordination costs low and enables intensive knowledge exchange, translating and transmitting NASA teams' valuable and proven expertise to everyone's benefit.

Third, we must leverage what is powerful and possible in both private and public sector spaceflight. NASA engineers are extremely innovative, but public spending mechanisms are limited. Corporations can move money around in ways public agencies can’t: inflating sticker prices on other off-the-shelf items, re-allocating research & development costs, or drawing on a billionaire's deep pockets to go deeply into the red in anticipation of future contracts. What corporations charge is rarely what it costs, and they have the flexibility to adjust the charge accordingly, unlike government organizations, which must maintain transparency and accountability. Companies can also derive long term savings from investing up-front in a production line, while NASA cannot muster enough annual Congressional support to do so. Yet corporations’ group know-how is far more susceptible to the winds of change when it comes to markets, employment, and investment strategies. Building on what each sector can do ensures we pair smart investments with continuity of knowledge.

Knowledge transfer and low-cost mission success often go hand in hand. A good example is the recent 2024 lunar landings, started largely from scratch after decades of lost Apollo know-how. While the press made much of the "New Space" companies that won contracts to fly to the moon, these teams worked closely with NASA centers and NASA experts. When Intuitive Machines' LIDAR mechanism failed prior to landing, NASA Langley partners stepped in to save the day. Without NASA know-how in the mix, the lander would have been a jumble of parts gathering dust on the moon--along with $77 million of taxpayer dollars.

Finally, we must keep a level head about the money involved. The amount of money that goes to NASA from an American tax dollar annually is a fraction of a penny. Twitter was purchased in one day for $44 billion; NASA science took sixty-five years to spend the equivalent on multiple probes, visiting Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the Moon, and half that price tag again bought breath-taking visits to Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Uranus, and Pluto. Every dollar spent at NASA returns three-fold to local economies and business innovations, introducing new products from Velcro to digital cameras to memory foam. Slashing Apollo saved money in the moment, but it sent $28 billion of taxpayers' investment in team know-how up in smoke. Similarly, gutting NASA’s Mars program today would lose us $36 billion--and the next space race besides.

What comes down may not go up

There is much to be gained from this new era of private spaceflight. Engineers at New Space ventures from SpaceX to RocketLab and Relavity Space are buzzing with new ideas, promising new forms of national pride, technical competence, and revenue. But slashing NASA's teams and centers with their hard-won group know-how now in anticipation of a commercial-dominant spaceflight future would not only represent a colossal waste of taxpayers' money—it would lose the knowledge America needs to retain its dominance in spaceflight. Far better to restructure and experiment with smaller-scale contracts and intensive pairings than to de-institutionalize the extraordinary group know-how that the US has so painstakingly acquired. If this next chapter of space exploration is to be dominated by new enterprise, we must build wisely on the sustained collective wisdom of NASA engineers. Otherwise, we are doomed to repeat the lesson of Apollo, putting the Moon and Mars even further out of reach.

The country should apply these lessons beyond space exploration. Strong technical and scientific agencies are the backbone of even the most burgeoning private sector enterprises, from medicine to computing: acquiring and disseminating team know-how that has made America a world leader in one sector after another. The US risks diminishing its hard-won advantages when we undermine our investment in these national institutions and strip them of their people and resources. As the moonshot teaches us, building up is much harder than tearing down.

Authors