How Congress Can Delete DOGE

Rebecca Williams / Feb 26, 2025

New York City, February 16, 2025 – Demonstrators at the Manhattan Tesla showroom protest Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency. Justin Hendrix/Tech Policy Press

Over the last three weeks, Elon Musk has delighted in boasting on his social media platform that he is deleting agencies, websites, and teams in unison with the Trump Administration’s larger project to claim unprecedented unilateral control over the federal government by flagrantly violating the law and the constitution’s separation of powers.

While it may be unlikely under Republican control of both chambers, I believe Congress can and should come together to restore its constitutional power by defunding and defanging DOGE before it is too late. I was a civil servant in two of the agencies DOGE is currently using as sock puppets to pillage the rest of the federal government: the General Services Administration (where I worked for Data.gov) and the Office of Management and Budget (working for the Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer). During that time, I gained valuable insights into the esoteric intricacies of government finance and operations, which are being so irresponsibly disregarded to the federal workforce and the public’s detriment.

However, one thing remains clear: Congress is in a budget deadlock, and DOGE’s parent agency, the US Digital Service (USDS), was never statutorily authorized. In the grand scheme of the appropriations process, DOGE’s budget can be deleted if Congress decides to act.

DOGE is a Dark Shadow of the USDS Playbook

While the Trump Administration has tried to have it both ways with DOGE—simultaneously claiming it is an agency for access to information and is not an agency for legal and compliance purposes, such as asserting Musk’s leadership while not officially installing him as the Administrator—DOGE clearly benefits from the bureaucratic infrastructure laid by USDS, including leveraging flexible hiring and spending authorities. In 2024, USDS employed approximately 220 personnel serving one- to four-year terms, most of whom were hired using Schedule A excepted service hiring authority, which excepts positions from competitive examination requirements to facilitate expeditious hiring. While this authority makes it easy to hire people quickly with fewer checks, it also means that legacy USDS staff—many of whom are facing imminent unemployment—do not have the same union protections as many other federal employees.

USDS also benefits from being funded by the Executive Office of the President’s flexible Information Technology Oversight and Reform (ITOR) account, the purpose of which, according to its appropriations language, is the “furtherance of integrated, efficient, secure, and effective uses of information technology in the Federal Government.” ITOR receives annual appropriations, adding to its large pot of "no-year" funds, which remain available for obligation indefinitely until it is expended. That makes its funding different from typical government appropriations available as annual or multi-year funds with defined periods of availability. ITOR has never had a programmatic direction or specific goals tied to its funding, unlike other more structured appropriated accounts that Congress funds—a flexibility feature that has quickly been revealed to be a massive loophole for DOGE operations.

During a joint hearing before the Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in 2016, a Republican Congressman from Texas, Will Hurd, had this exchange with the first USDS Administrator and ex-Google employee Mikey Dickerson:

Rep. Hurd. …But the mentality of the startup mentality in the Federal Government where it comes to disruption it is important, but the Federal Government doesn't have the appetite for the level of risk that the startup community has or the venture world has, all right. And so that's the one thing that doesn't transfer between, you know, with that narrative. And we have a responsibility to all of our constituents, which is the American people, that we're using their money wisely and smartly. I think these programs conceptually are great Programs. And my first question, and maybe we start with you, Mr. Dickerson, how do you decide what projects you work on?

Mr. Dickerson. It's a very complex process. I will try to make it brief. I spend a tremendous amount of time, and my other members of the leadership team spend a tremendous amount of time gathering information from all over the government. The agency leadership, stakeholders everywhere…

Rep. Hurd. Can I make a suggestion? That work is already being done. There's a GAO high-risk report. That high-risk report identifies some of the key projects that are a billion dollars or more that are having issues. All right? Does that make sense? Is that, you know, the flexibility and the way that you all could be used?

This early conversation echoes through to the present day, where members of Congress from both sides of the aisle have been concerned that USDS is moving fast and breaking things, while not aligning with the democratic wishes or oversight information provided by the legislative branch.

DOGE also benefits from a number of cyber-libertarian talking points that assert technology development and user experience research as replacements for legal fixes or policy change via democratic processes like voting, public comment, or protest. USDS, much like Big Tech, benefited from favorable press treatment with headlines like America's Tech Guru Steps Down—But He's Not Done Rebooting the Government and The Government Has Its Own Tech Startup, and It's Fixing a Lot. From its start until it effectively transformed into DOGE, USDS leaders insisted that the agency must bypass bureaucratic processes to inject Silicon Valley innovation into government services. This marketing strategy has effectively shrunken the imagination in civic technology circles away from solving the root causes for poorly functioning government services—like complex means-testing and underfunding—to a narrower Overton window where administrative rules like the Administrative Procedures Act, the Paperwork Reduction Act, and the Privacy Act—the very laws powering the court orders restoring government websites under DOGE—are the main problem and technology is the only counterbalance to bad policy. Rather than advocating for public healthcare or streamlined tax policy, many civic technologists argue for consumer tech solutions and for making government ”‘as easy as ordering takeout.” To achieve these transformative ends, USDS called itself a “SWAT team” of private-sector tech experts deployed into federal agencies. In 2017, a former government official summed up the fears about USDS’ tactics:

USDS leadership would frequently go around the deputy CIO, the CIO, the Deputy Director for Management, the Director of OMB, and the White House deputy chief of staff to bring issues to the President… After this happens several times and there are real questions about USDS’ ability to produce on the ground, then the question becomes, ‘We created this monster with a personal relationship with the President and how do we rein it in?’

Now, the USDS playbook has been weaponized by DOGE, which has sent its recruits on detail to agencies to wreak havoc on government programs through technological administration, including keyword lookup, website shutdowns, and unprecedented and likely illegal attempts to access sensitive personal information at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Department of Education, NASA, the Social Security Administration, the Treasury Department, and USAID. Unfortunately, rather than reflect on how the discretionary powers of USDS have contributed to DOGE's actions, many prominent past leaders of USDS have published pieces defending DOGE’s tactics, taking issue only with the current leadership goals. Their pieces suggest that only the people in power are the problem and offer no suggestions for systemic fixes to prevent this clear abuse of discretionary power.

Lastly, the ”spirit of civic technology,” as studied by academics and emblematic in USDS and now DOGE, has been found to reinforce Big Tech's influence in the government. For example, there is a revolving door of former USDS staff who now benefit from government access and government funding, such as ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt’s involvement in national security matters and influence over the Department of Defense’s spending, Palantir’s involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic response, and ex-USDS staff running a large government contractor like Rebellion Defense.

This pattern has already been evident in Musk’s actions during his brief tenure with DOGE. Lawmakers and legal experts are raising concerns about potentially citing DOGE’s attempt to access sensitive financial data and its role in dismantling regulatory agencies. These moves may benefit Musk’s 6 companies who are currently under 32 investigations. Additionally, questions are raised about whether Musk’s companies—such as Tesla, SpaceX or xAI—could receive preferential treatment due to Musk’s proximity to key agency decision makers and close ties with President Trump.

How to Defund DOGE

As concern about DOGE and its tactics and impact mounts across the country, there is a way for Congress to reassert its Constitutional role. Congress has the power to delete DOGE’s budget sources and effectively stall DOGE’s bureaucratic dismantling by prohibiting any funds from being used to carry out its activities. The Constitution grants Congress the power to appropriate and direct funds. In last year’s appropriations law, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2024, ITOR–the fund powering USDS–was appropriated $8,000,000.

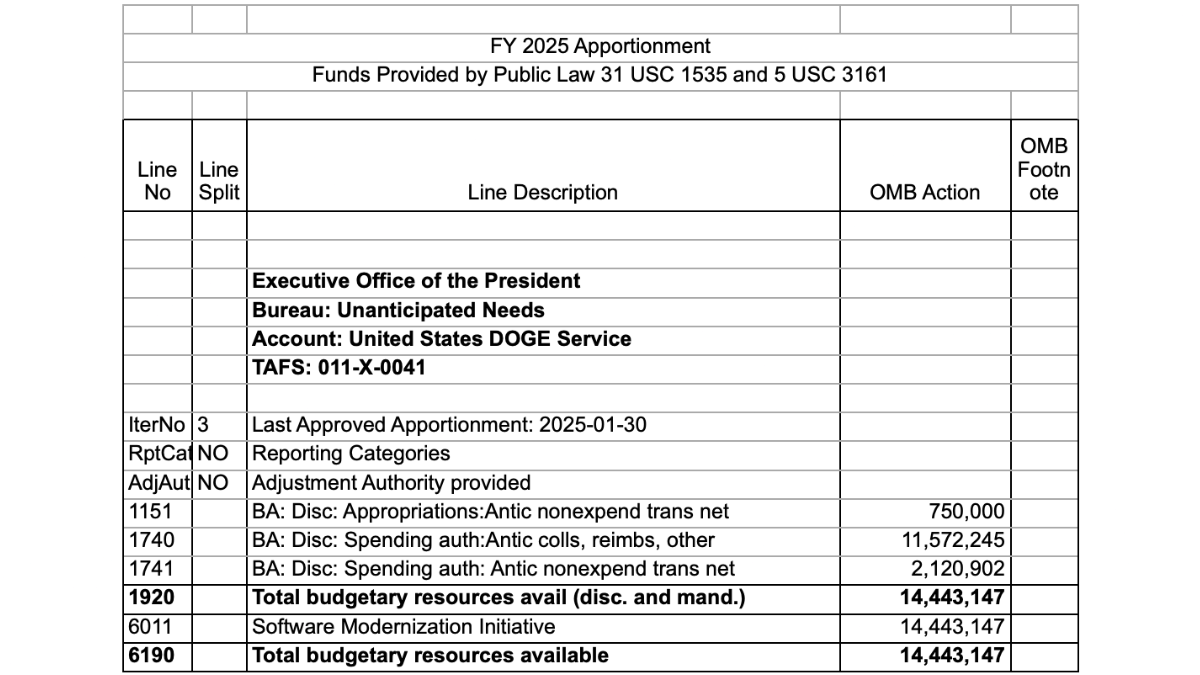

In addition to recurring appropriations to ITOR, Congress appropriated $200 million to USDS (and thus ITOR) under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) to use through the end of fiscal 2024. Lastly, agencies may reimburse USDS/DOGE for services using the Economy Act transfer authority. According to public appropriations data, as of this writing, $56 million from these funding sources has been apportioned by OMB for “Unanticipated Needs” related to digital services or software modernization since January 27, 2025. Records indicate that $39 million came from Economy Act transfers, and the remainder came from yearly ITOR appropriations, with $39 million apportioned to DOGE explicitly, as reported by ProPublica last week. See this example apportionment table:

Image via a screengrab of EOP apportionment data on Apportionment-public.max.gov

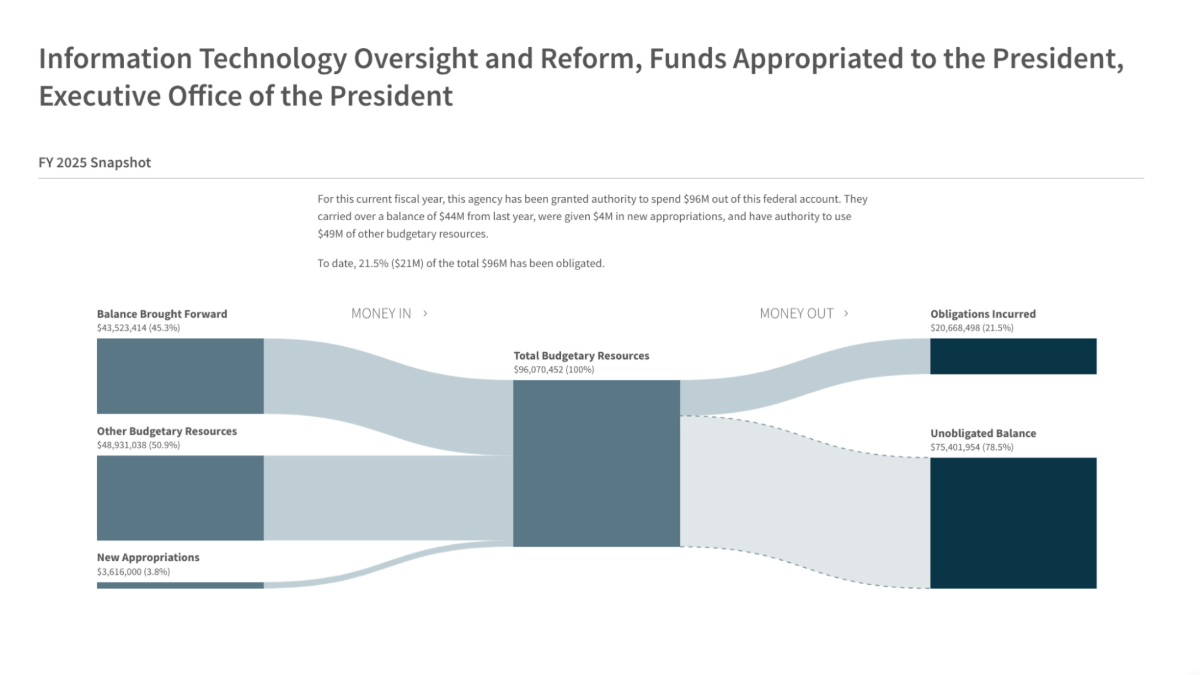

USASpending.gov indicates that ITOR currently has the authority to spend about $75 million of unobligated funds, money that has been appropriated over the years but not yet committed for expenditure.

Image via USASpending.gov

While the amount of funding technically available to DOGE is staggering, both funding sources can be clawed back so long as the money is not obligated. Congress can find all references to this funding via their respective laws (Public Law 118-47 and Public Law 31 USC 1535 and 5 USC 3161) and replace it with a provision that rescinds all unobligated funds authorized for USDS or any successor or related entity, along with a governmentwide general provision stating that “no funds shall be spent.” It could also insert a prohibition on using these funds for DOGE-related purposes. Alternatively, Congress could instead direct those unobligated funds to specific programs at agencies under statutory mandates with greater Congressional oversight.

Of course, this would require political will. Congress can come together to restore the constitutional separation of powers and remove one of the few avenues for DOGE’s dismantling of the administrative state and various government programs. Over the years, members of Congress from both sides of the aisle have begun to scrutinize ITOR more closely and cut its funding. Officials who have served in both the Executive and Legislative branches have raised the alarms on USDS’s accountability. Further, there are a number of Republican members of Congress who have gone on record (even if anonymously) voicing concerns about DOGE’s activities. If all Democrats and key Republicans have the courage, they can delete or renegotiate DOGE’s main source of funding and legitimacy and begin to restore Congress’ role in overseeing the activities of federal agencies.

What Happens If We Don’t Defund DOGE

Sadly, the DOGE crisis will likely have a moment of acceleration if Congress does not come to an agreement on an overall appropriations deal by March 14 and the federal government shuts down and furloughs government workers. In previous administrations, OMB and OPM have provided exceptions to all workers paid out of ITOR due to potential cybersecurity risks. This means that DOGE will have well established precedent while most federal workers are furloughed and continue their attempts to access government data and dismantle systems, perhaps with less resistance. If federal workers are furloughed in March, some may never return to work.

Congress must take this opportunity to stop DOGE in its tracks. Please join the members of the public who are speaking up at town halls and protesting DOGE and demand that your representative defund and thus delete DOGE to restore federal government stability and not prevent additional harm.

This piece was updated to include additional clarity on the three sources of DOGE funding: ITOR, ITOR ARP, and Economy Act transfers.

Authors