Don’t Be Fooled: Much “AI” is Just Outsourcing, Redux

Janet Vertesi / Apr 4, 2024

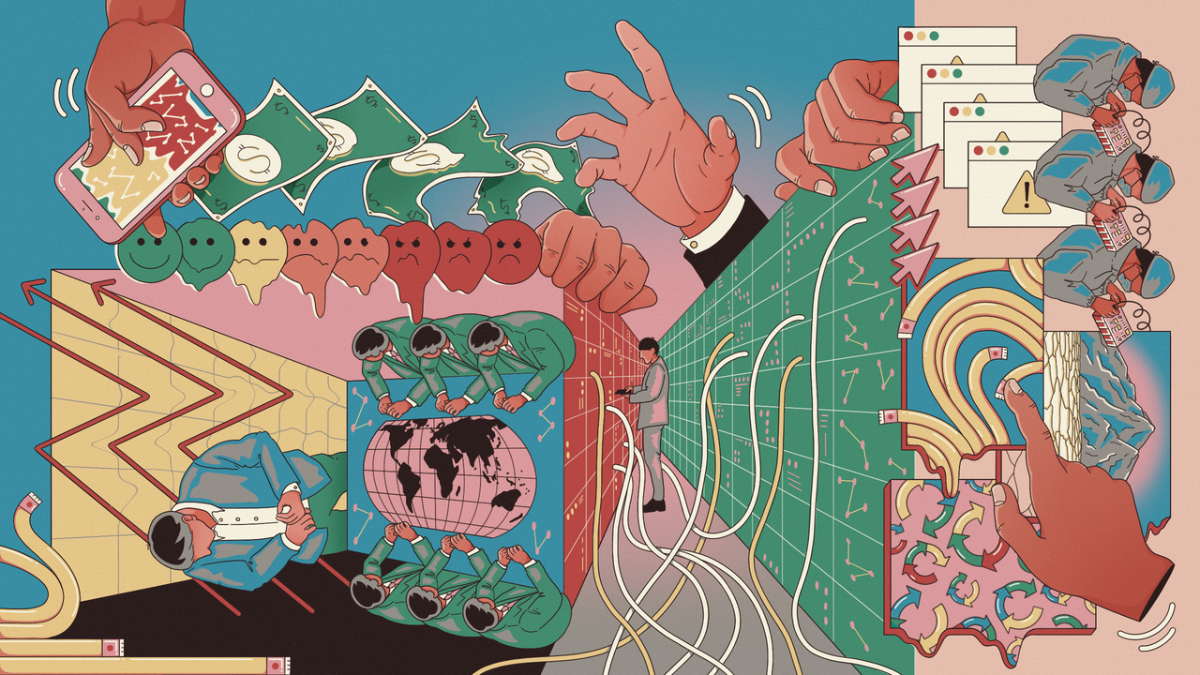

Clarote & AI4Media / Better Images of AI / Power/Profit / CC-BY 4.0

Your automated cashier isn’t an AI, just someone in India. Amazon made headlines this week for rolling back its “Just Walk Out” checkout system, where customers could simply grab their in-store purchases and leave while a “generative AI” tallied up their receipt. As reported by The Information, however, the system wasn’t as automated as it seemed. Amazon merely relied on Indian workers reviewing store surveillance camera footage to produce an itemized list of purchases. Instead of saving money on cashiers or training better systems, costs escalated and the promise of a fully technical solution was even further away.

The promise of AI, for corporations and investors, is that companies can increase profits and productivity by slashing their reliance upon a skilled human workforce. But as this story and many others show, AI is just today’s buzzword for “outsourcing,” and it comes with the same problems that have plagued outsourced companies and workforces for decades.

Amazon’s story is far from unique. Years ago, Microsoft teammates Mary Gray and Siddarth Suri called this “ghost work,” blaming it on the “last mile” problem of automation: the ever-receding horizon of what a computer is able to accomplish instead of a human. Meta’s army of invisible content moderators magically make unpleasant material vanish from your newsfeed at the expense of their mental health, according to UCLA’s Sarah Roberts. In a brand-new book, sociologist Benjamin Shestakofsky relates life at a startup whose US-based engineering team was so busy interviewing recruits and scaling up to please its investors that it offshored its entire “AI” product to workers in the Philippines who responded to tasks one at a time. Colleagues at Princeton and I have described a process we call “pre-automation” where companies employ humans to perform the tasks promised by automated systems, extracting unpaid labor and investment capital on the one hand, while deregulating a sector in favor of a monopoly on the other.

“AI,” in these cases and many others, is a shiny distraction that begs us to “pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.” But behind that curtain is the familiar phenomenon of outsourcing: expensive, skilled labor in the US or other advanced economies traded for cheap, unskilled labor in developing economies.

Indeed, the job losses associated with “AI” are reminiscent of the losses associated with industrial decline in the late twentieth century. These losses accumulated in a geographical location or a market sector as the workforce shifted offshore to emerging markets, where many more people are required to do a less skilled version of the job for less pay. As investors looked to skim ever more off the top, the US transformed into a “knowledge economy” dominated by a managerial tier but hollowed out of technical expertise.

The creative accounting techniques that brought us “fast fashion,” off-shore call centers, and even the ill-fated Boeing MAX-C are the very same ones that inspired Amazon to install empty checkout stands fueled by Indian workers whom they expected could do the same work for less. But studies show how outsourcing adds inter-organizational complexity and communication challenges, driving up inefficiencies and decreasing consumer quality. Meanwhile, studies of automation show resulting increases in labor needs and inequalities, requiring both new skilled laborers to supervise the machines and more workers to take up lower-skill roles. As anthropologist Lilly Irani observes, labor is not replaced by machines, it’s merely displaced. While stocks surge upon restructuring, few companies achieve this promise of savings and profitability, and “bullshit jobs” soar.

The story of AI distracts us from these familiar unpleasant scenes. Instead, we envision a glistening “future of work” in which we are all miraculously more efficient, our workplaces are populated with relentlessly pleasant robots, and expert automated agents fulfill our every command. Pundits talk loftily about the “ethics of AI” as if it’s a technical question of ironing out its biases or building BB-8 instead of The Terminator.

But the future of work is not a technology: it’s an arrangement. An arrangement of people, capital, and workers that moves jobs from where they are expensive and highly-paid, to where they can be cheap and menial. “AI” is a powerful decoy, lest we start thinking about where those jobs have already gone – offshore – and who moved them there in the first place. Because robots aren’t “taking our jobs” – people are.

We should be wise to the shiny veneer of new technologies and futuristic promises in pitches about “AI.” This is simply old wine in a new bottle. And as the Amazon case makes clear, it’s already turned to vinegar. US policymakers and workers alike would do well to heed the lessons of the last forty years of outsourcing and its effects upon the labor market, and move quickly to legally protect the skilled workforce at home and avoid shortchanging partners abroad. Clients of AI-embracing firms should demand they maintain high-level experts on production’s front lines and resist downsizing or reducing complex jobs to menial tasks. And the next time a CEO flashes a pitch deck festooned with mentions of AI, investors should follow Amazon’s lead and Just Walk Out.

Authors