Imagining Meaningful Surveillance Tech Policy Implementation Through Real-World Research

Kate Kaye / Jan 22, 2025Kate Kaye is a multimedia journalist and researcher living in Portland, Oregon. The investigative research described here was conducted in her personal capacity, and this article solely reflects her personal research and opinions and does not reflect the research, opinions, or strategies of her employer.

A DJI Matrice 30T drone, similar to the models used by Portland Police. Shutterstock

On an October evening in Portland, Oregon, in 2023, police used drones to locate three juveniles, then detained and identified them. They were alleged to have been passengers in a silver Lexus sedan Portland Police Bureau officers followed that night in a black, unmarked car through a Northeast neighborhood. The pursuit began after the Lexus driver made two turns without signaling and then accelerated. But police officers lost sight of the Lexus. When they discovered it abandoned nearby, officers launched four drones into the dark autumn sky, to assist in locating the people they believed had been in the car. In the end, the juveniles were released. The alleged driver of the car was never located.

This is just one anecdote, a single example of the sort of drone use by law enforcement happening every day around the world. In Portland, the story reflects one of many situations in which police have used drones – devices equipped with cameras that zoom in on people, track them from a distance, and share images and precise location coordinates of those people’s movements in real time. It is just one example in a city where police drone use has increased drastically, from no more than 18 times a month between June 2023 and October 2024 to more than 40 times in November 2024.

The details of the events of that October night – gleaned through a police case report obtained via a public records request – have broader relevance. They illuminate gaps in surveillance tech policy and police tech use procedures, helping inform how policy could be implemented to provide more meaningful transparency. Whether in Portland or some other municipality, investigative research and analysis of situations like these might even improve government tech accountability.

A Real-World Case Study in Local Surveillance Tech Use to Inform Policy

In February 2023, the Portland City Council unanimously passed a surveillance resolution that requires city bureaus to assess their use of surveillance-related tech, such as traffic safety sensors, police license plate readers – and, yes, drones. The policy calls for the development of a privacy protection program, an inventory of surveillance tech owned or used by city bureaus, related reporting, and accountability and oversight procedures. And it lays the groundwork for potential future policies addressing algorithmic and AI-based technologies.

I was at Portland City Hall reporting for Bloomberg CityLab the day the City Council voted to pass the resolution. As I researched the story in the days before the vote, I learned that the Portland Police Bureau was planning to pilot a drone program. Much to my surprise, the existence of that planned program had gone unreported.

A photograph from the Portland city government website of a police drone in use. Source

Drones, of course, are a form of surveillance tech. The nascent police drone program presented a timely and relevant opportunity to understand and articulate the implications of the policy that had just passed through observation, data, research, and analysis. Here was the seed of a real-world case study in local surveillance tech use about to come to life before our very eyes! Understanding how police use drones could lend much-needed context and help inform how the city might put its surveillance resolution into practice, not just for drones but more broadly for all surveillance tech.

Tech Capabilities: Procurement Records and Product Manuals

What types of data do the drones owned by the Police Bureau generate and capture? What communities are affected by drone use? To answer some of these initial questions, I analyzed procurement documents obtained through public records requests that showed the specific drone models and equipment the Police Bureau acquired in 2023 as it got its pilot program underway. (The documents are now available publicly on DocumentCloud.)

But just knowing the names and costs of drone models wasn’t enough. Additional research based on device manuals and technical specifications helped paint more of the picture by detailing the particular capabilities of each type of drone the Police Bureau owns.

By revealing important information about the surveillance tech owned by the Police Bureau, analysis of these procurement documents and product manuals was a step toward imagining what implementation of the surveillance resolution could look like in the real world. Notably, all of the drones acquired by the Portland Police Bureau in the time evaluated, many if not all of which are still used today, were made by a popular drone manufacturer based in Shenzhen, China. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) warned in January 2024 against the use of Chinese-manufactured drones, also called Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS).

The resources evaluated for this initial research also served as examples of the types of information Portland City agencies might make available through the implementation of the surveillance resolution, including when they request approval and funding from the Portland City Council for surveillance tech acquisition and use. Already, cities including Madison, Oakland, San Francisco, and Seattle publish information or notifications about surveillance tech owned and used by city agencies including police.

Community Impacts: Census Data and Community Demographics

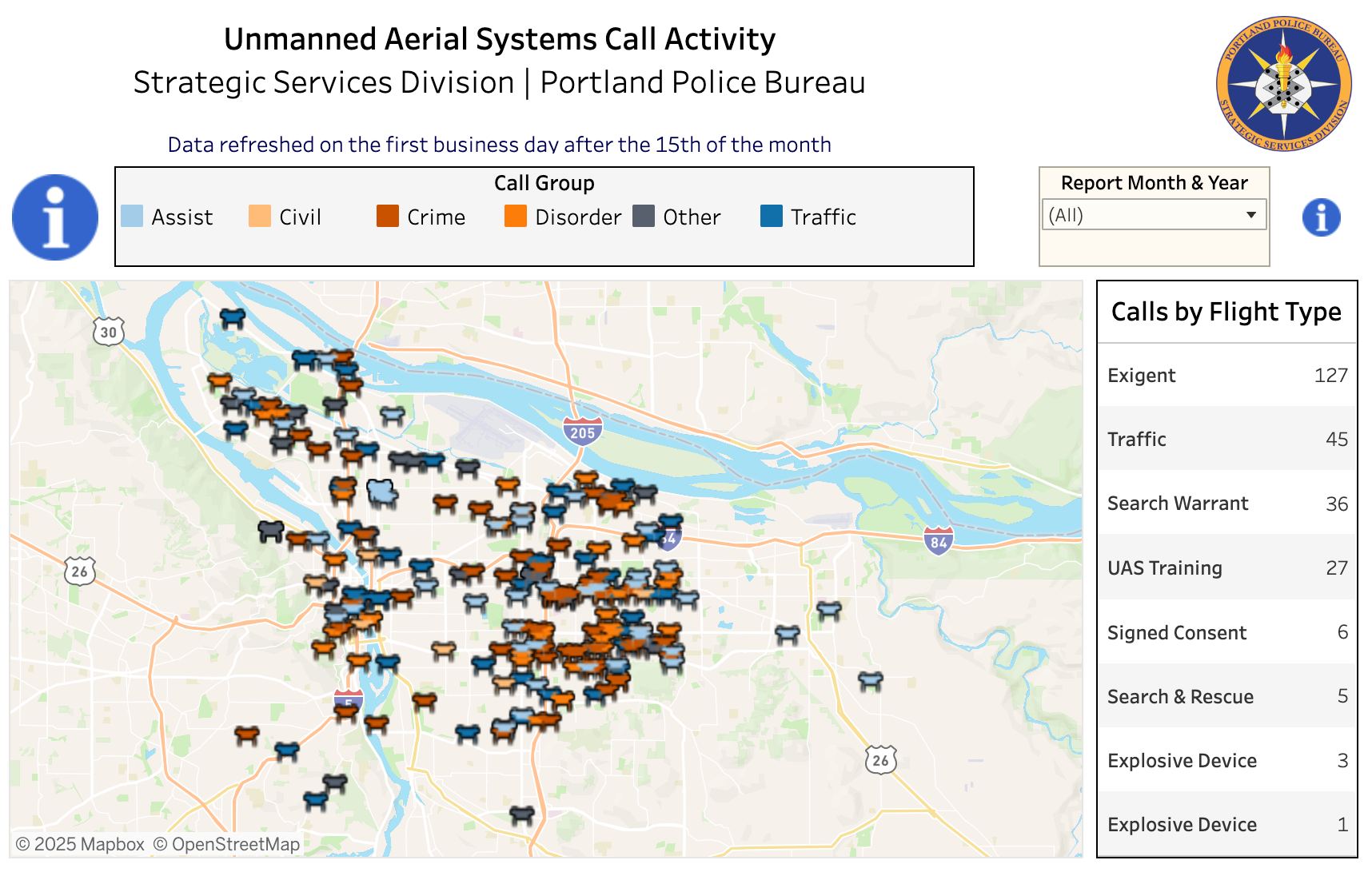

The Portland Police Bureau offers a welcome glimpse into otherwise opaque police surveillance tech use through its public Unmanned Aerial Systems Call Activity website. Even in the early days of its pilot drone program, the open data available there showed that the Police Bureau had flown drones more often over a particular region of Portland – east of the Willamette River. The Willamette River cuts vertically through Portland. Generally speaking, it separates many of its wealthiest populations on the West side from its most marginalized and impoverished on the East.

A screenshot of the public dashboard maintained by the Portland Police Bureau that presents an interactive map allowing users to filter drone flight data.

In the hopes of understanding more about the populations affected by police drone use, I analyzed that publicly available drone data in conjunction with US Census data, finding that in many cases, Portland police drones had been deployed in neighborhoods where more people of color live and where poverty rates are higher than in other parts of the city and Portland as a whole.

Today, this East-West divide remains. According to my more recent evaluation of the Portland Police Bureau’s public data, 172 – or 91% – of the 189 police calls involving drones flown for non-training related purposes between June 2023 and November 2024 occurred over areas east of the Willamette. There are all sorts of reasons why police might fly drones in certain neighborhoods. However, as the city considers how best to evaluate surveillance tech acquisition and use, and how best to implement its surveillance resolution, it is important to recognize this discrepancy and consider what it tells us about the community impacts of surveillance tech use.

Already, a Portland lawmaker has recognized the importance of demographic information related to drone use. When the Portland City Council voted unanimously in September 2024 to expand the police drone program and boost funding to buy more drones, then-City Council Commissioner Dan Ryan suggested that demographic information might be provided in some way in the public drone data. Ryan and police representatives acknowledged privacy considerations that could limit the publication of demographic data; however, Portland Police Bureau Chief Bob Day told Ryan that he would ask the city attorney whether demographic information could be released, noting, “I would hope that we would be able to release that.”

As of 2025, Portland has embarked on an entirely new approach to City Bureau management and expanded its City Council. Ryan continues to serve, now as one of three Portland City Councilors representing District 2, east of the Willamette in north and northeast Portland.

Actual Drone Use: Digging Deeper with Police Case Reports

There was more to learn. The next step was to understand how Portland Police officers actually deploy drones and under what circumstances. Despite offering only limited transparency, the Police Bureau’s publicly available Unmanned Aerial Systems Call Activity data facilitated this research by indicating dates, times, approximate locations, and types of police drone flights. I used that data to inform additional record requests. In particular, I filed requests for 10 police reports involving the use of drones in situations that seemed incongruent with the Police Bureau’s stated program purposes. (I requested case reports related to drone flights labeled as “Suspicious subject, vehicle or circumstance,” “Traffic Stop,” “ECIT [Enhanced Crisis Intervention Team],” and “Behavioral Health.”)

My analysis of the only three full police case reports I received, along with additional reporting, indicated important information that could help policymakers and other stakeholders understand actual drone use. The analysis informs police drone operating procedures as well as the implementation of the surveillance tech resolution. (I received only three full police case reports and other partial reports and related documents.)

For instance, the research revealed that officers flew a drone inside a family’s apartment to “clear” it before they entered in search of a suspect who was later arrested, raising questions about data privacy and consent procedures. It also indicated that when Portland Police Bureau officers used four drones in October 2023 to locate three juveniles – leading to their detainment, identification, and eventual release – officers may have had the drones inside their patrol car ready to launch at a moment’s notice. It is unclear whether such immediate accessibility of the devices conformed with the Police Bureau’s drone operating procedures.

The research also showed the limits of the police’s publicly available drone data, indicating opportunities to improve surveillance tech transparency. For example, we have no idea the total area over which officers flew four different drones that October night because the public data provides the same exact individual set of latitudinal and longitudinal geographic coordinates for all four of the drones.

Not only have Portland Police drones been launched in the vicinity of sensitive locations, including places of worship and medical or mental health recovery facilities, but they have been flown in searches over what could be very large areas of Portland. Flight log data generated by the actual types of drones Portland Police own includes flight pattern and joystick pattern data that indicates where drones were flown and how they were used during flight.

All Surveillance Tech Policy Is Local

When it comes to tech policy, Portland has been seen as a model for other cities to follow. Portland City Council passed a groundbreaking facial recognition ban in 2020 that went further than most by restricting use in privately owned places as well as by the city government. The establishment of the city’s surveillance resolution itself is relatively rare for local government, as is the existence of public data about police drone flights.

However, in many ways, Portland is no different from countless municipalities around the world. Budgets are tight. Staff and resources are shrinking. Elected officials and staff have limited time to evaluate the tech they use, fund, and govern. Meanwhile, as local media outlets shrink, the city could benefit from additional expert investigation of city government tech use – whether it’s surveillance tech such as police drones or automated and algorithmic systems that determine water bill discount recipients.

No government should get a pass to limit oversight and transparency around surveillance tech use while at the same time funding expanded use of that tech. As the research and reporting described here demonstrates, Portland can do better to maintain its position as a model for accountable and equitable tech policy. Particularly as city bureaus look to automated and algorithmic systems in the hopes of reducing labor costs and workloads, Portland can foster a more comprehensive understanding among policymakers and residents about tech use and ensure that tech policy implementation enables meaningful accountability.

In the meantime, as Portland’s surveillance resolution takes shape, I aim to continue this research and hope it might inspire more efforts like it in other places where people have the ability to question their government.

Put simply, government tech use happens everywhere, including inside your City Hall and on the streets of your hometown. While so much attention is focused on national and international tech policy, there’s a lot some of us can do to make an impact on genuine government tech accountability in our own neighborhoods.

Authors