Digital Public Services for Whom? Participation and Care as Prerequisites for Efficiency

Maria Luciano / Dec 17, 2024

São Paulo, Brazil. Shutterstock

The debate around digital public infrastructures — that is, the digital capabilities necessary for the interaction between governments and people — remains in full swing. Brazil continues to lead globally in this area with initiatives like Pix and Gov.br, which have fostered financial inclusion and improved public access to public services.

In this context, the recently published Brazilian Federal Digital Government Strategy is encouraging. It outlines the concrete actions that will guide the Federal Public Administration's digital government efforts through 2027. However, for an action plan aimed at addressing the governance of such efforts, the new strategy — like the Brazilian National Digital Government Strategy before it — falls short on a key element of any democratic governance model: the participation of all people, sectors, and stakeholders affected by these policies.

While the recommendations regarding coordination across federal, state, and municipal levels, and between agencies and entities at the same level have been robust, the involvement of civil society organizations, affected communities, the private sector, academic institutions, and international organizations — despite being acknowledged as important by the government — still needs greater attention.

Participation is not only a democratic requirement but also a prerequisite for the efficiency of digital policies. If adopted throughout the entire lifecycle of these policies, well beyond the minimal oversight role traditionally assigned to civil society after the technology has been deployed, participatory governance can reduce risks, speed innovation, and drive sustainable adoption, as argued by Jeni Tennyson.

Gov.br, Brazil’s digital identification system for accessing public services, provides a good example to reflect on governance and legitimacy. Its requirement for biometric data to create silver and gold accounts, the ones giving access to the most public services, goes against the growing concerns among Brazilians about the use of such data by the government and financial institutions. According to a recent survey carried out by the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee, 60% of Brazilians are either “concerned” or “very concerned” about having to give away their biometric data, and these concerns are mostly directed at financial institutions and government organizations. It also disregards the higher susceptibility to errors in facial recognition faced by vulnerable populations, such as Black and transgender people. This poses questions on the necessity of this biometric data collection, the advancement of techno-solutionist narratives, and even public policy communication (if this data collection is really necessary, is the public being efficiently informed as to why?).

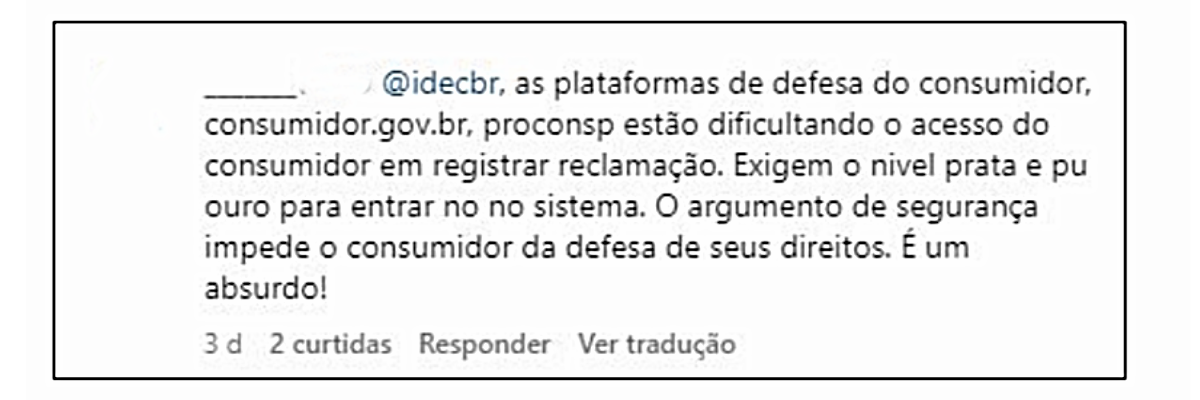

A 2024 social media post directed at the Brazilian Institute for Consumer Protection - IDEC: “The consumer protection platforms are making it difficult for consumers to file complaints. They require silver or gold status [at Gov.br] to access the system. The argument of security is preventing consumers from defending their rights. It's absurd!ˮ - Screenshot provided by Maria Luciano

Similarly, the lack of dialogue with affected stakeholders during the implementation of Pix has contributed to inefficiencies in its Special Refund Mechanism (MED), a grievance redressal mechanism created to reimburse consumers for amounts stolen through fraudulent Pix transactions: 9 out of 10 Brazilians are unaware of what the MED is and how it works, and only 9% of the MED requests made in 2023 were reimbursed. These participatory deficits also hinder the resolution of emerging issues, such as the use of Pix for messaging, which has enabled practices of harmful speech and gender-based violence and even questionable direct marketing campaigns.

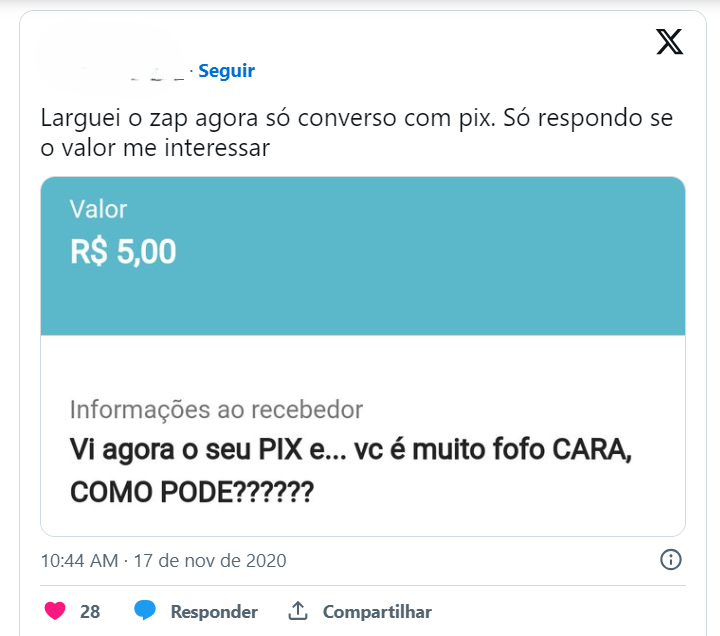

A November 2020 social media post: “I left WhatsApp and now will only chat through Pix transactions. And I will only replay if the amount interests me.” Amount: BRL 5.00. "Information to the receiver: I just saw your Pix transactions, and… you are very cute. How is it possible?" - Screenshot provided by Maria Luciano

Cases like these highlight the need for a holistic, people-centered, and care-informed policy approach, focusing on the impact of digital policies on people's lives far beyond their interactions with government apps and platforms — the so-called “user experience” or “user-centric.” In this sense, the ethics of care provides a critical lens that complements a human rights-based approach, which can fail “to encompass or challenge the way social norms and institutional patterns of power can serve to perpetuate current patterns of inequality, creating a feedback loop between policy, norms, and the way people live their lives.” After all, before accessing these systems and becoming "users," individuals may need to overcome obstacles such as the cost and time required to travel to a computer, device, or internet access point or even arrange childcare to be able to do so.

Public shame stemming from a lack of knowledge or vulnerable conditions — sometimes reinforced by the treatment received from the public administration — also deserves attention, as it is linked to the reluctance to seek redress for losses resulting from Pix scams.

This phenomenon has been previously observed among Bolsa Família beneficiaries — a conditional cash transfer program that currently reaches 13.1 million families or 40.8 million people — and undocumented adults during birth certificate issuance. In her ethnographic research on Bolsa Família, Mani Tebet Marins describes many cases where "even though she was clearly facing economic hardships, she chose not to apply for the benefit precisely to avoid possible humiliation and prejudice from State representatives." In a similar work on undocumented adults, journalist Fernanda da Escóssia reported one case where “shame led her, in a relationship of nearly two years, not to tell her boyfriend that she was undocumented. Her testimony shows that this shame transcends the boundaries of domains we are accustomed to seeing as separate: the public and the private. Shame is not limited to being questioned at the hospital, the health clinic, or during interactions with agents and state offices. It is present in intimate relationships, in dating, and in the domestic sphere.”

How, then, can we ensure that public policies effectively address people's demands and needs? Through inclusive and participatory governance models.

On one hand, the uncritical adoption of technologies can exacerbate existing structural inequalities. On the other hand, ignoring technology's potential benefits risks discouraging innovation.

To navigate this impasse, it seems essential for efficient public policies to ensure that diverse and qualified voices are heard. To empower society and equip people with the necessary technical capacity and capabilities while acknowledging the valuable knowledge behind their lived experiences. There are promising examples to guide this path: tutorials and training programs for humanitarian aid to help seniors and people unfamiliar with technology; Bogotá’s “care blocks,” which offer services like legal and psychosocial assistance, professional training, and recreation; or even the inclusive and participatory use of long-established tools like public procurement, rights impact assessments, and investments conditioned on private actors prioritizing and delivering direct benefits to the population.

The path to efficient digital policies — both in quality and scale of adoption — relies on social participation and care. Echoing the African philosophy of Ubuntu: I am because we are.

If you want to engage with the topic of digital public infrastructures, the UN’s Universal DPI Safeguards is currently accepting contributions and inputs here.

Related Reading

Authors