Status of State Laws on Facial Recognition Surveillance: Continued Progress and Smart Innovations

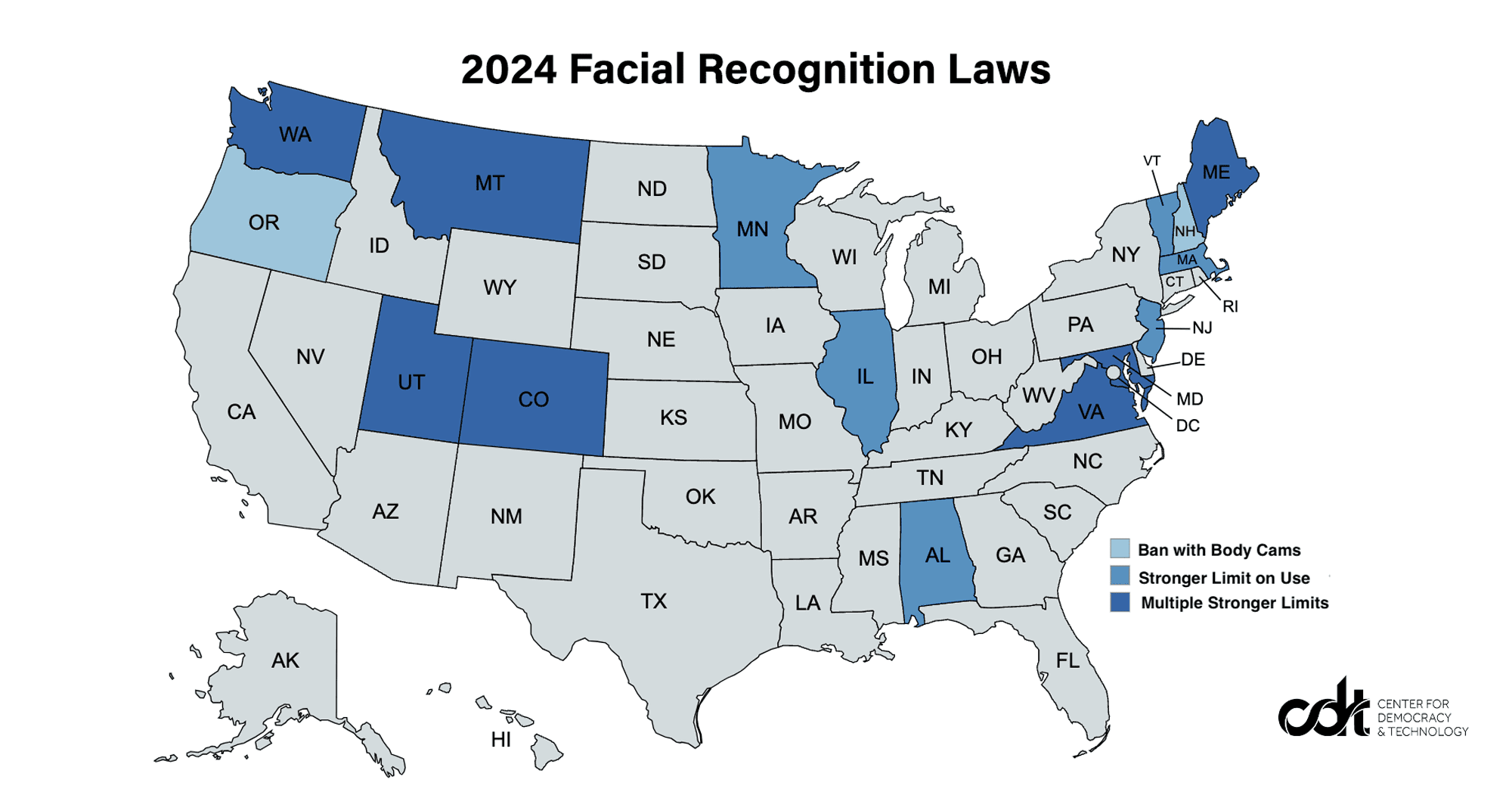

Jake Laperruque / Jan 6, 2025Over the past several years, a number of US states have taken significant steps to limit police use of facial recognition technology. In 2017, Oregon became the first state to do so, but the scope of its law was very narrow, limited only to the use of facial recognition in conjunction with police body cameras. By the end of 2024, fifteen states have laws limiting police use of facial recognition, with increasingly strong guardrails. These laws — enacted in states with a broad range of partisan ideologies — will protect the civil rights and civil liberties of millions of Americans and should spur further action.

Amid many hypothetical and emerging concerns about artificial intelligence, facial recognition stands out as an AI technology that is already broadly deployed and presents significant dangers to civil rights and civil liberties. Although federal legislation to place guardrails on law enforcement use of facial recognition has been introduced, Congress has not acted despite the seriousness of the issue.

The states, in contrast, have been far more proactive. As CDT documented in 2022, there has been steady momentum on this issue at the state level, with a growing set of states enacting increasingly strong regulations for police use of this AI surveillance technology.

Image shows a map of state facial recognition laws across the US in 2024. Light blue denotes 2 states — New Hampshire and Oregon — that ban use of facial recognition in combination with police body cameras. Medium blue denotes 6 states — Alabama, Illinois, Minnesota, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Vermont — that have a stronger limit than the body camera law on police use of facial recognition (such as a warrant requirement, notice requirement, or serious crime limit). Dark blue denotes 7 states — Colorado, Maryland, Maine, Montana, Utah, Virginia, Washington — that have that have multiple stronger limits on police use of facial recognition.

Continued momentum for safeguards and breaking new ground with warrant requirements

Over the past two years, steady growth of limits on facial recognition surveillance has continued. In 2022, a dozen states had restrictions on facial recognition. As 2024 concludes, that number has increased to 15. Perhaps even more notable than the ever-increasing number of states restricting facial recognition surveillance is the strength of the new laws: One state (Maryland) enacted a set of important policies, while two others (Montana and Utah) became the first states to require a warrant for police use of facial recognition.

The Maryland law — enacted earlier this year — includes a number of regulations, with two items standing out as essential safeguards: (1) The law limits police use of facial recognition to investigating a set of serious crimes enumerated in the law, and (2) it requires that prosecutors notify defendants that facial recognition was used in an investigation that led to the charges that were brought.

Montana and Utah, meanwhile, broke new ground by becoming the first states to enact a warrant requirement for police use of facial recognition. Montana did so in 2023, passing a law with not only a warrant rule but also a serious crime limit and notice requirement. In 2024, Utah followed suit, enacting a warrant requirement to strengthen the state’s existing limits on facial recognition (which had previously established a serious crime limit). Both laws include sensible exceptions, such as for emergencies and identifying a missing or deceased individual.

A warrant requirement should become the foundation for facial recognition policy going forward. This rule simultaneously is a strong shield against abuse and should have little disruptive effect on legitimate law enforcement needs. This is because the primary manner in which the technology has proven useful to police is by identifying an unknown perpetrator in an image showing them committing a crime. In this scenario, the photo itself provides probable cause, meaning obtaining a warrant will not be an onerous hurdle. At the same time, such a rule will block off nefarious uses of facial recognition, such as cataloging the identities of protesters (an abuse that’s already occurred) or tracking who enters a house of worship.

There are some differences in how the Montana and Utah warrant rules function. The Montana rule requires a probable cause showing that an individual to be identified with facial recognition is the perpetrator of, victim of, or witness to a serious crime. This last category raises some concern: While police may have a legitimate reason to seek out the identity of a witness, it also creates the risk of abuse built around “surveillance by association.” For example, if one individual at a large protest committed an assault, that might be used as a pretext to catalog the identities of dozens of other protesters simply because they were in the vicinity and theoretically could be witnesses. Removing this provision (or at least enacting an exhaustion requirement to make its use contingent on investigative necessity) would help ward off abuse.

The Utah rule, in contrast, requires a warrant to “obtain biometric surveillance information” (without speaking to whether the warrant could be used to obtain biometric information from non-suspects). Biometric surveillance information is defined in the Utah law as “analysis of surveillance information using biometric software to identify an individual's identity or location using the individual's physical attributes,” which clearly encompasses all police uses of facial recognition to identify individuals. The law does exempt from the warrant requirement the use of facial recognition at law enforcement buildings, critical infrastructure, courthouses, public schools, and airports, or when there is “a documented reasonable articulable suspicion of a threat to commit a violent felony by a specific individual.” This type of preemptive exception would appear to permit untargeted scanning of crowds in certain cases, a dangerous deployment of facial recognition in circumstances where the risk of misidentification is high, and use on non-suspects is routine. Thus far, there are no documented uses of such untargeted scans by US law enforcement (although pilot programs were run in the United Kingdom, with extremely high rates of error). Further work is needed to develop rules in this space: In addition to rules needed to account for accuracy problems with untargeted facial recognition, “reasonable articulable suspicion” is too low a standard, and there should be judicial review and approval to make sure standards of suspicion are met.

Animated GIF shows map of the US with the progress of facial recognition laws over time: In 2017, 1 state banned use of facial recognition with police body cameras. By 2019, 5 states had banned use of facial recognition with body cameras. By 2022, 3 states had banned use with body cameras, 6 states had a stronger limit on use of facial recognition, and 4 states had multiple stronger limits on use of facial recognition. By 2024, 2 states ban use with body cameras, 6 states have a stronger limit on use of facial recognition, and 7 states have multiple stronger limits on use of facial recognition.

Courts and litigation begin having an impact

Legislatures are not the only space that has moved states forward in limiting facial recognition surveillance — courts are also becoming critical. One state — New Jersey — established a regulation for facial recognition not through legislation but rather a court ruling. In 2023, a New Jersey appellate court ruled in New Jersey v. Arteaga that defendants must be notified of police use of facial recognition in investigations to protect their due process rights to review potentially useful and exculpatory information (a Fifth Amendment protection often referred to as “Brady Rights” established by the Supreme Court in Brady v. Maryland (1963)). The Arteaga ruling is both significant and sensible given that a huge array of information about how police use facial recognition could be critical to defendants. The algorithm employed or system settings could show unreasonable potential for error, as could the use of a low-quality image as a probe photo or efforts by law enforcement to alter the image (a frequent problem). How police treated potential matches to other individuals (facial recognition systems usually generate a candidate list of multiple individuals rather than one single “match”) is also important, as is information on how facial recognition shaped future investigative actions.

A requirement to provide notice to defendants is critical because although facial recognition can play a major role in arrests, including mistaken ones, police usually keep its use hidden. The addition of such a requirement in the past two years in New Jersey, Maryland, and Montana, which builds on prior existing requirements in Colorado and Washington, is a promising development. Civil rights and civil liberties advocates in other states should look to legislatures and courts alike to build on this effort.

Litigation has helped regulate facial recognition in Detroit as well. Legal action by Robert Williams — the first individual known to be improperly arrested and jailed due to a facial recognition error — and the ACLU culminated in a legal settlement earlier this year. The settlement requires Detroit police to adhere to a number of new policies and procedures aimed at limiting overreliance on facial recognition and preventing unjustified arrests such as those Mr. Williams and many others since then have suffered. For example, police cannot use facial recognition systems without receiving training on the risks and dangers of the technology. The settlement also requires that defendants be informed when facial recognition was used and given details on the nature of its use.

Detroit police also must obtain evidence to corroborate a facial recognition match before an individual is placed in a photo lineup; a different photo than the one returned by a facial recognition system must be used, and police may not tell a witness reviewing a photo lineup that a facial recognition match was found. These requirements are a meaningful improvement over the prohibition against reliance on facial recognition matches as the “sole basis” for an arrest adopted in seven states (Alabama, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Virginia, and Washington) Under a sole basis rule, a facial recognition match could serve as the primary, even overwhelming basis for an arrest. Or it could cause confirmation bias and taint future investigative efforts. For example, in one documented case, an NYPD officer asked a crime witness to confirm an identification of a single match photo returned from facial recognition, which violated procedures for photo lineups. Similar occurrences have since been documented, as well as police impacting witness identification by describing their use of facial recognition to place an individual within a photo lineup.

By going significantly beyond the no “sole basis” rule, the measures in the Detroit settlement establish meaningful guardrails that can help prevent overreliance on facial recognition and the improper arrests stemming from it. Experts and stakeholders should continue to examine what other rules could supplement these measures, and the many states that have enacted a sole basis rule — as well as states working towards limiting facial recognition in the future — should adopt this more comprehensive approach.

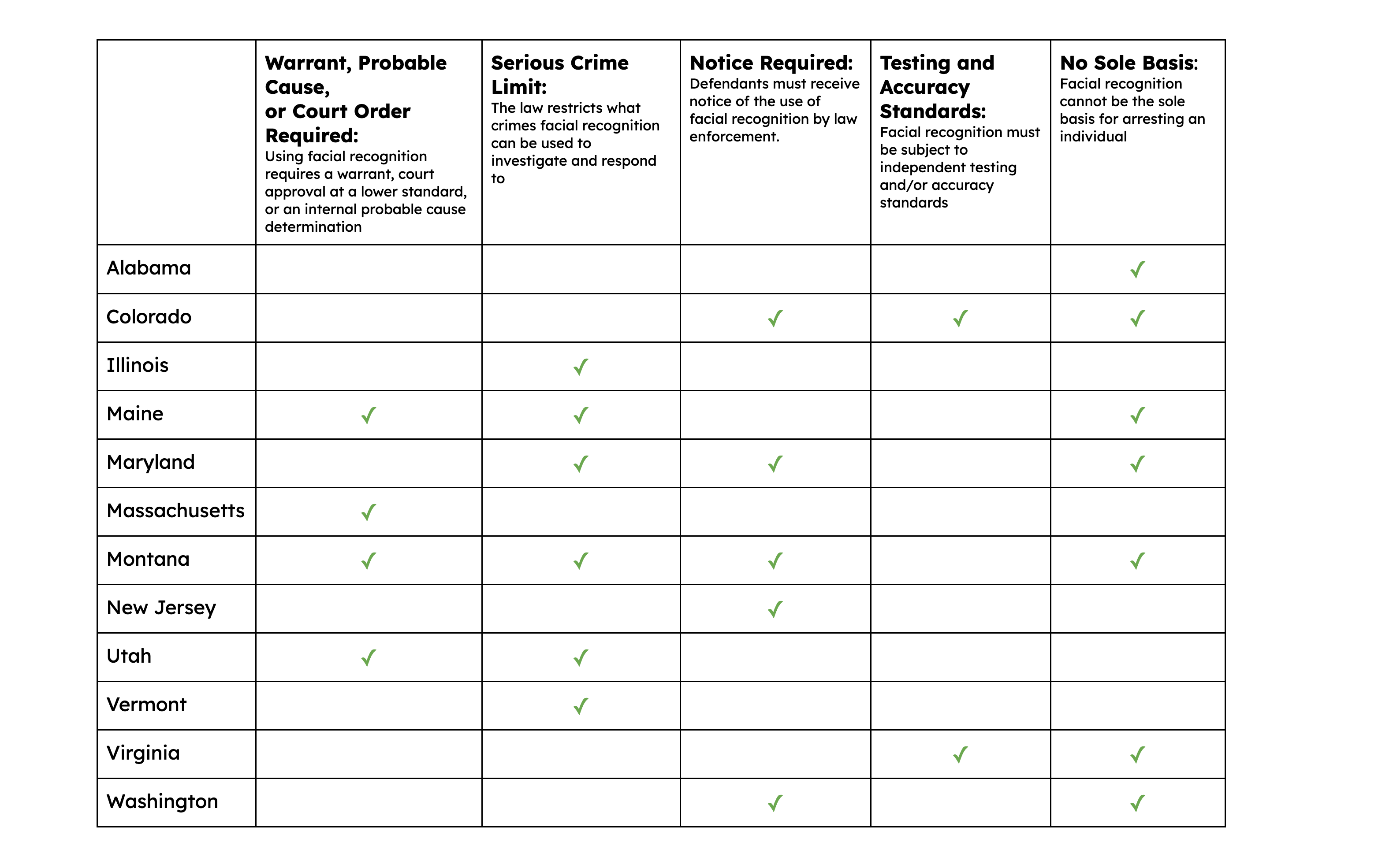

Below are the most notable requirements for police use of facial recognition in the states that currently impose limits:

Chart documenting which states have certain facial recognition rules: A warrant, probable cause, or court order is required in 4 states: Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, and Utah. A serious crime limit exists in 6 states: Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Utah, and Vermont. Notice is required in 5 states: Colorado, Maryland, Montana, New Jersey, and Washington. Testing and accuracy standards are required in 2 states: Colorado and Virginia. Facial recognition cannot be the sole basis for an arrest in 7 states: Alabama, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Virginia, and Washington. Three other states also have weaker protections: Oregon and New Hampshire prohibit facial recognition use with body cameras, and Minnesota prohibits facial recognition use with body cameras.

Setbacks in one state

While the last two years generally continued the trend of more states enacting increasingly strong limits on facial recognition, California was an exception. There, a law prohibiting the use of facial recognition in conjunction with body cameras expired in January 2023. Since then, it has not been reenacted or replaced by more substantive measures. It’s disappointing to see a state that has been a leader on many privacy issues — such as CalECPA, the California Consumer Privacy Act, and the California shield law to protect reproductive health information — move to the back of the pack on facial recognition. Hopefully, next year, we will see renewed engagement from the state in addressing this issue.

A promising path ahead for limiting facial recognition surveillance

Progress in limiting facial recognition surveillance is likely to continue. Legislators in Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and West Virginia have previously introduced legislation to limit police use of facial recognition. Placing safeguards on its use has broad appeal across the political spectrum. As the need to regulate AI surveillance becomes more urgent, hopefully more states — and Congress — will prioritize enacting strong limits on facial recognition into law. And hopefully, the increasing number of states that already limit this surveillance technology can serve as examples not only of how to shepherd such policies but also of why limits on facial recognition can better protect people’s rights while also accounting for public safety needs.

This post is part of a series examining US state tech policy issues in the year ahead.

Authors