From Freedom of Speech and Reach to Freedom of Expression and Impression

Richard Reisman / Feb 14, 2023Richard Reisman is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at Lincoln Network, media-tech innovator, and frequent contributor to Tech Policy Press.

Managing society’s problems related to how (and by whom) social media news feeds are composed is rapidly reducing to the absurd. Elon Musk’s capricious management of Twitter highlights many of the core elements of the presenting problems – while related issues have risen to the Supreme Court. It is time to step back from those proverbial trees to reconsider the forest, and consider a reframing that promises to make many of those problems more tractable from human rights, legal, governance, economic, cultural, and technological perspectives. The essence is to focus on the other end of the proverbial “megaphone” – not the speaker’s end, but the listener’s. Social media platforms are co-opting the “freedom of impression” that we listeners perhaps did not realize we had – instead, humanity needs them to enhance it.

Collective intelligence – or collective idiocy?

In his recent analysis, New York Times media correspondent Michael Grynbaum alludes to “Citizen Musk,” and how this new press baron on steroids makes Hearst and Murdoch seem like pikers. Musk’s suspension of several journalists “sparked an outcry…from First Amendment advocates, threats of sanctions from European regulators, and questions about the social media platform’s future as a gathering place for news and ideas…as people debate complex, novel issues of free speech and online censorship.” Many of those accounts were later reinstated, after Musk polled Twitter users. Such uses of Twitter polls are to platform governance as thumbs downs are to gladiatorial governance – a veneer of mob rule over a whimsically brutal dictatorship.

Looking beneath the froth of current news, this circus matters deeply, because -- frivolous as Twitter often is, and aberrant as its new owner may be -- it really has become an essential “town square” for journalists, as Grynbaum highlights; for scientists fighting Covid, as Carl Bergstrom explains; and for many other self-organized communities. And it facilitates those communities’ abilities to interconnect with one another – as an internet of ideas (however limited as yet). Many users are already seeking a replacement for Twitter. Whatever that alternative may be, humanity needs these essential networks to work better.

Joe Bak-Coleman explains that Musk is at least somewhat right that Twitter represents an initial step toward a “collective, cybernetic super-intelligence.” He and Bergstrom tease out many nuanced issues that we must get much better at dealing with to help make humanity smarter, collectively -- instead of dumber, disruptively, as we now seem to be doing. Even if Twitter implodes, the need for such collaborative services – and their proper governance -- will grow as our world grows ever more challenging and interconnected.

Reduction to the absurd

Absurdity is strong evidence that a thesis is incorrect, and that applies to our thesis for managing social media feeds. Social media are too globally interconnected for any single point of control to govern responsively over what each of us sees in our individual feeds -- least of all a single impulsive media baron. But that applies to any private corporation, whether controlled by a “better” media baron, or a “responsible” governing board. As Molly Land argues, “platform law” is inherently authoritarian and antithetical to democracy. It is for similar reasons that the First Amendment prohibits government control (direct or indirect).

Current trends toward decentralizing platform law may further complicate the challenges. Mastodon’s “fediverse,” a confederated network of social media services, is now in vogue as a Twitter alternative that counters excessive centralization by localizing communities. However, those communities are still under the control of a hopefully-benevolent dictator, even if more siloed and escapable.

It seems we have yet to remember that the much-maligned 1996 U.S. law, “Section 230,” says that “It is the policy of the United States… to encourage the development of technologies which maximize user control over what information is received by individuals…who use the Internet…” The octopus of platforms has enticed us to forget that. And, the extreme decentralization of the fediverse continues to pay only limited heed to it.

Two absurdities walk into the SCOTUS bar

But current problems are far deeper and more fundamental, Grynbaum points to the current furor over the “Twitter Files” and how that triggered “a broader discussion over the role of social media platforms in deciding what ideas circulate online.” Musk was accused of censoring liberal journalists, and he, in turn, accused them of crying foul when similar actions by the previous management of Twitter censored conservative viewpoints.

Meanwhile, a cluster of cases governing these issues of online speech are now being raised to the Supreme Court. One considers a wildly controversial Texas law mandating that online platforms must carry speech that is lawful but awful, while other cases related to terrorist content consider whether to expose platforms to liability if they inadvertently place such material into someone’s feed. Democracy rests on open discourse -- how can it flourish if that is stifled, drowned in pollution, or both? That seems an intractable dilemma, as Daphne Keller recently explained.

What people are allowed to say and do online is one of the most important and troublesome questions of the information era. Because of the role of online communication in modern democracy and discourse -- whether you call it a “public square” or not -- resolving tensions around online speech is necessary to help society make progress on its other problems. It’s true that moderation of online content faces serious technical challenges today, but the root problems are not of technology but rather of human social dynamics -- and of legitimacy. What speech should be restricted as harmful? By whom? In what way? How should online media be managed to serve citizens and society?

A reframing of how online speech should be managed

Contrary to some hot takes, this reduction to the absurd is not a signal of fundamental flaws with the freedoms of the First Amendment, or in the Section 230 provision that limits online platforms’ liability for carrying harmful online speech. Rather, it is our current understanding of how speech can be managed in social media, search, and other online services that must be reframed – both the mechanics and the principles. With a clearer understanding, those freedoms can guide us forward. Barrie Sander argues that, while no panacea, “a human rights-based approach would mark a significant shift towards a more structured and principled approach to content moderation.” Let’s rethink how freedom of expression can be maximized without undue harm in this new era of online media.

The online information environment is a radical transformation, still dimly grasped -- it is hyperconnected in a newly reflexive way that explodes far beyond what any individual can absorb. Internet users depend on an individualized filtering layer to select from the speech of billions, by recommending and ranking desired content into their attention, while downranking the unwanted. Without that selectivity, our "news feeds" would be a firehose, too overpowering to drink from, and too irrelevant and noxious to even try.

But who can and should have the power to select what a user hears – to manage the risk of excluding too much or too little? As explored by Chris Riley and me in a series in Tech Policy Press, the policy of user control underlying Section 230 provided a wise strategy for dealing with this dilemma -- but we forgot it. Refocusing on user control is the way to find a flexible balance that works for each listener -- and the communities they participate in -- with sensitivity to whatever context they find appropriate.

Instead, citizen attention is now being shaped by platform control of our news feeds and recommendations -- intensifying a perfect storm of paradoxes. Over-exclusion wrongly suppresses important valid ideas and assemblies (not getting what you desire), while over-inclusion wrongly impresses noxious ideas and assemblies (getting what you wish to avoid).

Popular platforms gain dominance over competing services because users gain value from a network with wide reach (“network effects”) -- plus large networks benefit from technology economies of scale. But the overpowering scale of speech on those platforms forces them to rely on computer algorithms that have poor ability to discriminate -- unlike human mediators who understand nuance and context. The governance problem is that unlike the very efficiently scalable task of interconnecting billions of users, scaling the moderating of their individual online feeds and recommendations is much more complex and nuanced, enjoying only limited network effects and scale economies, and inherently inefficient. That is why these tasks need to be managed and governed in very different ways.

In 2018, Reneé DiResta suggested Free Speech Is Not the Same As Free Reach, but few have yet taken her point to heart, and many apply it operationally in inconsistent ways. Perhaps that’s because the concept of reach derives from print and TV advertising, suggesting the speaker’s (or advertiser’s) perspective. There is also the platform’s perspective on reach: selling our attention to advertisers who want to reach us. But what about the listener’s perspective?

Better to consider the pairing of speaker and listener rights more explicitly. When viewed with a one-sided focus on the speaker’s freedom of expression (including that of the advertiser or platform), speech rights face an impossible balance of interests, because speakers crave reach. But the picture inverts when one broadens the frame to include the listener’s perspective: what they want to hear. That highlights the underlying problem as new and profoundly undemocratic limits on freedom of impression -- by the platforms. The platforms are not just gatekeepers of the speaker’s end of the megaphone, they shape whether the sound waves going through it come out to reach an individual listener – or not.

The listener’s perception of a speaker’s expression that reaches them is that it makes an impression on them. The foundational concern, then, is whether unaccountable and undemocratic platforms should be permitted to individually manipulate what is impressed on each of billions of listeners’ attention. Clearly problematic when a dominant platform is the only way for a listener to listen to their desired communities!

Freedom of expression requires freedom of impression!

The idea of freedom of impression seems unfamiliar only because it has been taken for granted. Philosopher and social theorist Jürgen Habermas delineated the emergence around the eighteenth century of the “public sphere” of citizen discourse, in the form of news media, salons, and citizen assemblies – even the grassroots informality of coffee houses – as central to the shift from the subjugation of feudalism to the freedom of democracy. With that, one became free to choose from a diversity of communities. If a citizen did not want to hear what was being said they could leave, to return another time – or find other communities. We had freedom of impression – a corollary of both freedom of expression and of assembly, and an essential component of freedom of thought.

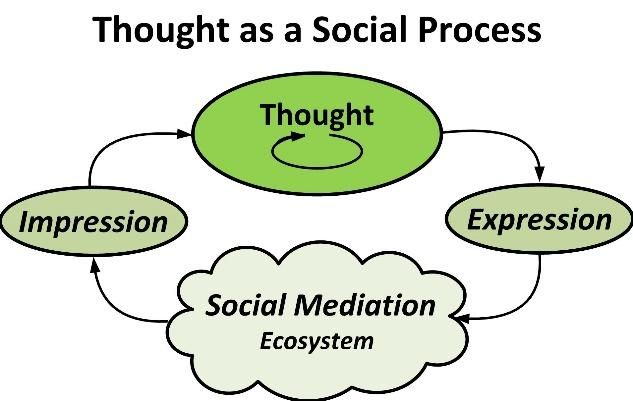

Freedom of thought, expression, and impression are not just isolated, individual matters, but an ongoing, cyclic, social process. Thought leads to expression, which then flows through a network of others – a social mediation ecosystem. That feeds impression, in cycles that reflexively lead to further thought:

But now -- just as network technology has made this process far more reflexive than ever -- the platforms have co-opted the freedom of impression that we did not realize we had. They have disintermediated the traditional mediating communities that we had chosen among to shape both our speaking and our listening. The problem will only grow as network effects and richer modalities of online communication continue to make moderation of content at scale increasingly impossible to do well, even with the best intentions There is just too much diversity in needs and values across communities, cultures, and geographies for “platform law” to govern -- the result is inherently authoritarian, overbroad, and underinclusive.

Compounding that, it has become increasingly apparent that we cannot rely on the platforms to have the best intentions. As platform oligarchs become the new absolute feudal lords of this public sphere, they gain influence that is far more dangerous than mere economic power. Guided poorly -- or for ill -- digitization can degrade the public sphere rather than enhance it. Governance of our public sphere must be managed democratically -- but how?

Back to the future of user control and delegation

Individual choice over what one sees or hears is key, but in our highly digitized and algorithmically mediated society it is difficult to maintain. As noted above, the enormous scale and complexity of the modern information ecosystem requires new abilities and controls for navigating the firehose of messages. Few individuals are willing and able to manage these choices without expert assistance and automated support. The platforms may make herculean efforts, but, at best, can do little more than a crude attempt that sacrifices nuance and context. But users do need help. So, we need filtering/recommender services that act as our agent – to serve our own interests, not the platform’s. To re-enable freedom of impression in such an environment, user control can be combined with expert assistance through “opt-in” delegation to these trusted agents. They can do the heavy lifting of ranking and recommending what speech seems worthy to be heard -- in ways that their users desire.

Certain U.S. Senators wisely recognized the need for a right of “delegatability” of user choices in the proposed ACCESS Act, and the EU has enacted similar provisions to empower “third parties authorized by end users” in its Digital Markets Act. But to what third parties would users delegate? A growing number of proposals advocate delegation of control of online feeds and recommenders to a new layer of mediating services that would work between users and the platforms. Such mediating services are often referred to as middleware* (because they fit in the middle) – but may be better understood as “feedware.”

These mediating services would grant agency to users (and their chosen communities) over which algorithms are applied, in what context, -- to shift from the platform (where control of impression is not legitimate), back to the listener (where control of impression is legitimate). Users could delegate control of their information impressions (their feeds and recommendations) to a mix of mediating services – whether new ones, or newly empowered extensions of existing communities, publishers, and other institutions.

Such delegation could enable citizens to associate with those having common interests and values, and draw on their collective support to mediate what comes to their attention. Do you want your feed to be influenced by communities who follow the New York Times, or Fox, or PBS, or your church or school, or some new affinity-based services? In what mix, with what weighting? With what level of professional editorial direction versus open crowdsourcing? Might that change as your activities and moods vary?

That could re-establish a robust and diverse information ecosystem – as a social process that guides freedom of impression. To attract members, these services might compete on strategies such as bridging designed to make discourse more positive and generative, countering current drivers toward polarization and performativity.

Democracy has long relied on such social processes to enable it to be both stable and creatively adaptive – to collaboratively favor quality, to find new ideas, and to discount disinformation. That collaboration minimizes the need for censorship, a bluntly draconian and stultifying tool. It self-organizes to motivate and teach participants to be discriminating and responsible, self-censoring as appropriate. Ethan Zuckerman expands on how social media might restore that behavior among citizens.

Consider that the “marketplace of ideas” is not flat but develops by building on a “marketplace of mediators” – analogous to how economic marketplaces have grown efficient and robust by building on a rich ecosystem of mediators (and regulators). This enables an emergent level of subsidiarity of control -- to retain context, integrate diverse solutions, and leverage social trust, in a way that maximizes openness, freedom, and social value.

Importantly, reliance on the nuance and context sensitivity of a mediating ecosystem leverages the reflexivity of how social media really work. They do not “amplify” directly from speaker to listener, like “megaphones” or mass broadcast media – where limits on citizen speech have been accepted as necessary. Instead, they propagate messages in stages, like traditional word of mouth, but greatly accelerated. Messages achieve virality or are ignored depending on the reactions of others (likes, shares, comments, etc.). Here, reach results largely from peer to peer social mediation, much as it had before mass media. But ensuring that social mediation is constructive, open, and diverse, requires an ecosystem from which citizens have agency to blend diverse sources of collective mediation to guide their listening. That ecosystem must become more adaptive and responsive than ever, to channel the newly accelerated and multi-faceted reflexivity that technology has driven.

Sharpening and deepening the focus

Interestingly, ex-Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey recognized this issue as central to Twitter’s moderation dilemma and funded a project called Bluesky that would facilitate such delegation and clearly distinguish a “speech layer” from a “reach layer.” Musk’s tweets show he has learned the “reach” lingo, but he seems to not understand the implications.

The “Twitter Files” have also drawn attention to how much Twitter had already been attempting to shift control from blocking speech to modulating reach. The problem is that Twitter’s modulation of reach is now done by the platform -- based on mechanisms that might operate to serve the objectives of the listener, but instead might just serve the platform’s own objectives (or its owner’s or the government’s). Alex Hern reports this confusion over legitimacy of “what Twitter calls ‘visibility filtering’, a form of moderation that is intended to impact ‘freedom of reach’ without affecting ‘freedom of speech’” such as with various “blacklists” and “do not amplify” lists -- and explains how concerns shift depending on whose ox is gored.

That highlights the ambiguity of reach as it relates to listener freedom and control of impression. If impression is not clearly controlled under the direction of the listener, then speakers who are not granted reach by the platform feel disenfranchised – sometimes quite rightly. But when impression is managed by the user -- or the user’s freely chosen agent delegate – then limitation of undesired reach clearly is legitimate. User-controlled limits on reach do not infringe a speaker’s rights of expression. Except in dystopias like Orwell’s 1984, we have always been free to plug our ears. Katherine Cross makes related points about how shadowbanning is often perceived as censorship, and is a transparency issue for Twitter. But, if that exclusion was imposed by a user agent, it would just be an obviously legitimate matter of the listener’s selective attention.

Three points of control

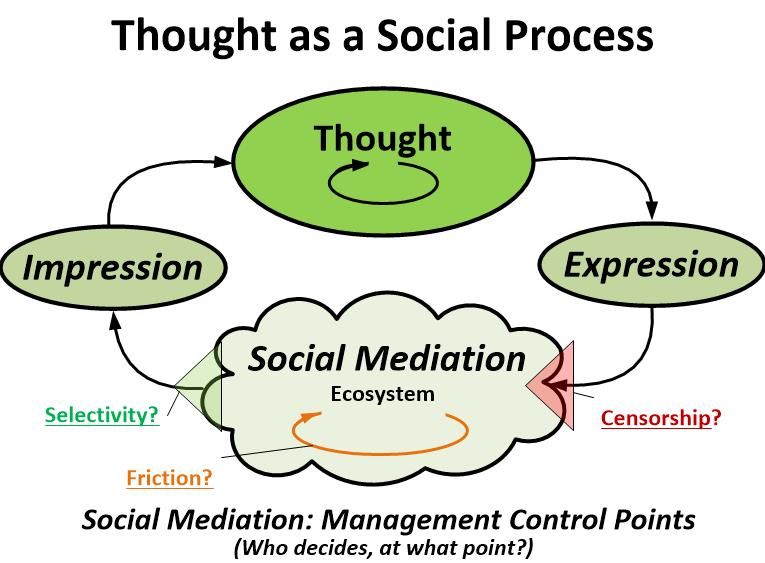

To more clearly operationalize how this applies to managing online content moderation, consider how the platforms have co-opted the social mediation process at three different control points:

- Most directly threatening freedom of expression is censorshipas posts and responses enter the network, entirely banning users or removing individual posts before they reach anyone at all. This is now done often by platforms as a moderation tool of first resort, when it arguably should be a last resort.

- Most directly threatening freedom of impression is selectionof what is fed or recommended out to each user, individually. This is now done routinely by platforms, leaving little agency to each user. As outlined here, it seems illegitimate and dangerous to democracy for anyone but users or their agents to have a dominant role in controlling this.

- Most like the organic process of traditional social mediation is friction and other measures to enhance the deliberative quality of human social mediation activity. (Keep in mind that friction can either retard or facilitate flows, as it creates viscosity to enable lubrication.) Platforms are beginning to recognize friction as more tractable and less draconian than censorship, but do it with little transparency.

Thinking more clearly about this process and the practical and human rights issues of which intervention control points are used, by whom, and how, can illuminate a path forward that cuts through current dilemmas and absurdities.

Back on track toward digital democracy -- distributed control of an open information ecosystem

Empowering user choice is not without difficulties. It will take time and intensive development – but can digitizing human society be easy? The bigger challenges are the social, legal, and business issues of changing course -- made harder after spending over a decade over-centralizing our digital information ecosystem. Lack of clarity and consensus on regulatory and antitrust interventions has been a major stumbling block to limiting that. But, as Daphne Keller explains, challenging as it may be, enabling this level of user choice may be the best way to sustain the strong freedom of expression that democracy relies on.

While regulation had seemed the only likely path, there are signs that this period of over-centralization might be peaking, in a way that could offer fertile soil for mediating agent services to enable more user choice. We may be seeing the twilight of the platforms (a Platformdammerung?), as the fediverse gains activity – and maybe we can also avoid over-decentralizing. I have suggested that primitive efforts at crossposting between the Twitter platform and the Mastodon fediverse may be creating a hybrid “plativerse.” As such interconnection and interoperability enables experimentation with nuanced structures for distributing control, shared middleware services may emerge organically to support these federated systems, as an efficient way to outsource and scale moderation tasks. That might also facilitate multi-homing our feeds to draw from a diverse aggregation of interconnection services and messaging modalities – thus further enriching the social mediation ecosystem.

Competitive innovation in such an open marketspace might generate a rich diversity of federated middleware services. (Call that “fiddleware” in echo of the “fediverse,” and because users can “fiddle” with it?) That can empower a high level of freedom of impression – so we can freely steer our “bicycles for the mind.” Much as I have proposed, and along with Bluesky and others, Zuckerman’s Gobo 2.0 project is a notable effort at similar ideas that would allow for a multiplicity of user-created “lenses,” combined with a multiplicity of third-party “scoring services.”

Finally, consider the most fundamental objection to enhancing freedom of impression: fear of democracy itself -- can society trust in individuals to make good choices? Can citizens resist the blindered comfort of echo chambers that reinforce views they already hold -- or being nudged into rabbit holes of disinformation and conspiracy theory? Would a top-down information diet control be better? But such paternalism would threaten the adaptive and generative interplay of expression, mediation, and impression. Protecting strong user freedom of impression is the only broad strategy for preserving strong freedom of expression in a world of global information feeds. Other remedies can complement that, not substitute for it.

Research is suggesting social media’s role in creating echo chambers is real, but narrow. Much as it always has been, the feasible challenge is not to stamp out all harmful content, but for citizens to be gently encouraged to cast a wide net, responsibly blending views from a diversity of mediating communities – and discouraged from antisocial and antagonistic behavior. That is primarily a social problem, and social mediation is how society always managed this problem. Technology should build on and augment that social process, not attempt to replace it.

User choice is essential to enable both strong freedom of expression and the complementary freedom of impression needed to balance it – and to enable nuanced mediation. That can be effected through delegation to -- and collaborative social guidance marshaled by – freely chosen feedware agents that comprise a “representative” information ecosystem. Restoring this essential right of user choice is essential to move forward toward digital democracy, rather than backward toward a new kind of platform feudalism. Along with a healthy and open social mediation ecosystem, freedom of expression and freedom of impression are both essential to democracy.

- - -

Thanks to Chris Riley for his insightful collaboration in developing these ideas in our series in Tech Policy Press, and to him and Renée DiResta for their advice in drafting this piece.

- - -

* The term 'middleware' that gained attention from Fukuyama’s Stanford group is perhaps fraught, because it has a prior meaning in software technology that may differ from the architectures for user choice that some advocate (such as Mike Masnick, Bluesky, and Gobo 2.0). I use that term advisedly, to broadly include any suitable mixture of server-based, protocol-based, and user client-based selection technologies to fit in the middle between the user and the networked content -- and believe most advocates using the term intend it as similarly broad. I previously favored the term infomediary (information intermediary) that was introduced by Hagel and coauthors in 1997 (and also relates to parallel efforts in data governance), but much of the social media policy community seems to have settled for now on the middleware term. I now suggest feedware as more functionally descriptive.

Authors