Digital Public Infrastructures in 2025: Where Do We (All) Want to Go?

Maria Luciano / Jan 30, 2025

Hanna Barakat & Cambridge Diversity Fund / Better Images of AI / Pas(t)imes in the Computer Lab / CC-BY 4.0

In 2024, digital public infrastructure (DPI) emerged as a particularly hot topic in tech policy and a priority for many governments across the globe, with the “50 in 5" campaign supported by the Gates Foundation, UNDP, Co-Develop, the Centre for Digital Public Infrastructure and the Digital Public Goods Alliance aiming to commit 50 new countries to deploy DPI within the next five years.

With no consensus around the definition of the term, visions relying on analogies of “DPI as roads” and “DPI as radio” have risen without much dialogue between those that advance them and fueled by narratives of innovation that, without proper safeguards and acknowledgment of risks, could lead to technocratic and elitist endeavors. To steer the dialogue toward DPI’s potential for inclusion and sustainable development, a series of important conversations are still necessary.

Only inclusive debates can lead to inclusive policies

In 2024, I co-facilitated DPI discussions within the C20, the Group of Twenty (G20) civil society engagement group. After a plenary, attendees of the Digitalization and Technology Working Group were given the option to join remote breakout rooms of a specific topic for debate. The first meeting of the DPI breakout room had only two participants who were not entirely sure of what would be discussed. It was not until we began using terms such as “digital government” or “digital public services” and examples to frame the conversation that people started to show up with many meaningful contributions. This episode, like many others I have experienced since, seems symptomatic of the current state of discussions around DPI, in which funders and international organizations take center stage through high-level convenings, with little data on how the deployment of these infrastructures has tangibly impacted people. But how can we create solutions that truly work for people without actually listening to them?

Participatory approaches enable processes to become transparent, accountable, and responsive to the needs of those participating in these discussions. Therefore, inclusive and meaningful participation entails working closely with the communities one aims to support to understand people’s experiences and design policies around their needs, perspectives, and potential unintended consequences. It also poses questions about who is empowered to participate and how: Sherry R. Arnstein warned us that participation can take many forms within a spectrum from extractive and tokenistic to empowering, even enabling the maintenance of the status quo when it fails to shift power structures and amplify marginalized people’s voices.

Efforts to leverage digital public infrastructures for their potential for inclusion must first address these challenges within the DPI ecosystem. Funding practices, which are rightly questioned, need to account for these power imbalances to level the playing field and ensure civil society has the resources and a big enough platform to develop effective counter-narratives and strategies as effectively as other actors do – or meaningfully collaborate with governments where that opportunity presents itself.

Moreover, capacity building can provide education, training, and support for those who need to understand and comment on complex technical issues. It enables the participation of grassroots organizations, community leaders, and “non-experts” who are the most knowledgeable about the needs of marginalized populations, thus challenging the “institutional credentialism and expert-lay divide that often shapes our public discourse,” as suggested by Ruha Benjamin.

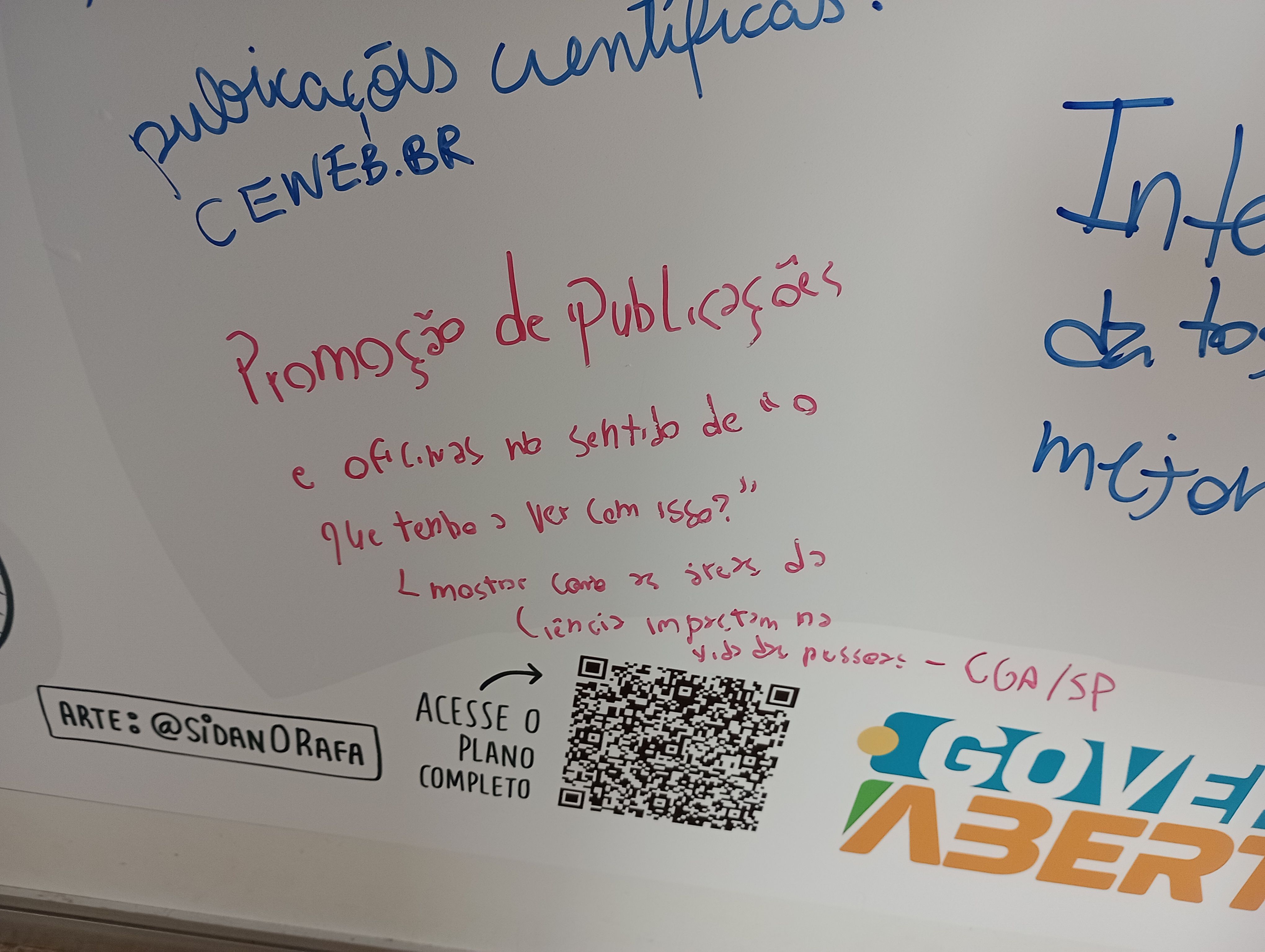

During Open America 2024, the Brazilian Office of the Comptroller General displayed a graphic facilitation of the 6th Brazilian National Action Plan in Open Government to gather hand-written contributions from participants. The one on the photo reads, “Promotion of publications and workshops under the theme ‘What do I have to do with this?’ to show how science impacts people's lives.”

The United Nations Universal DPI Safeguards Initiative provides a starting point to address some of these participatory deficits, which are not new. While most discourse surrounding DPI emphasizes its technical aspects, the Initiative has done great work in shedding light on how these infrastructures are embedded in social systems.

As the Initiative enters its second year aiming to update its framework drawing from public inputs, support its in-country implementation, and assemble a new cohort of working group members, it will have the opportunity to establish participatory processes to build trust in and forge the legitimacy of the project. These processes should include, at the very least, representative recruitment and outreach; engagement through inclusive convenings and workshops; accountability of governments who commit to implementing the framework; and responsiveness and transparency towards the received inputs, as the final decision on proposed recommendations will rest with the UN Secretariat. Otherwise, it will risk turning itself into a form of “window dressing” to approve the Secretariat’s preferred policies and a “black box,” discouraging people from putting in the time and effort to engage with it.

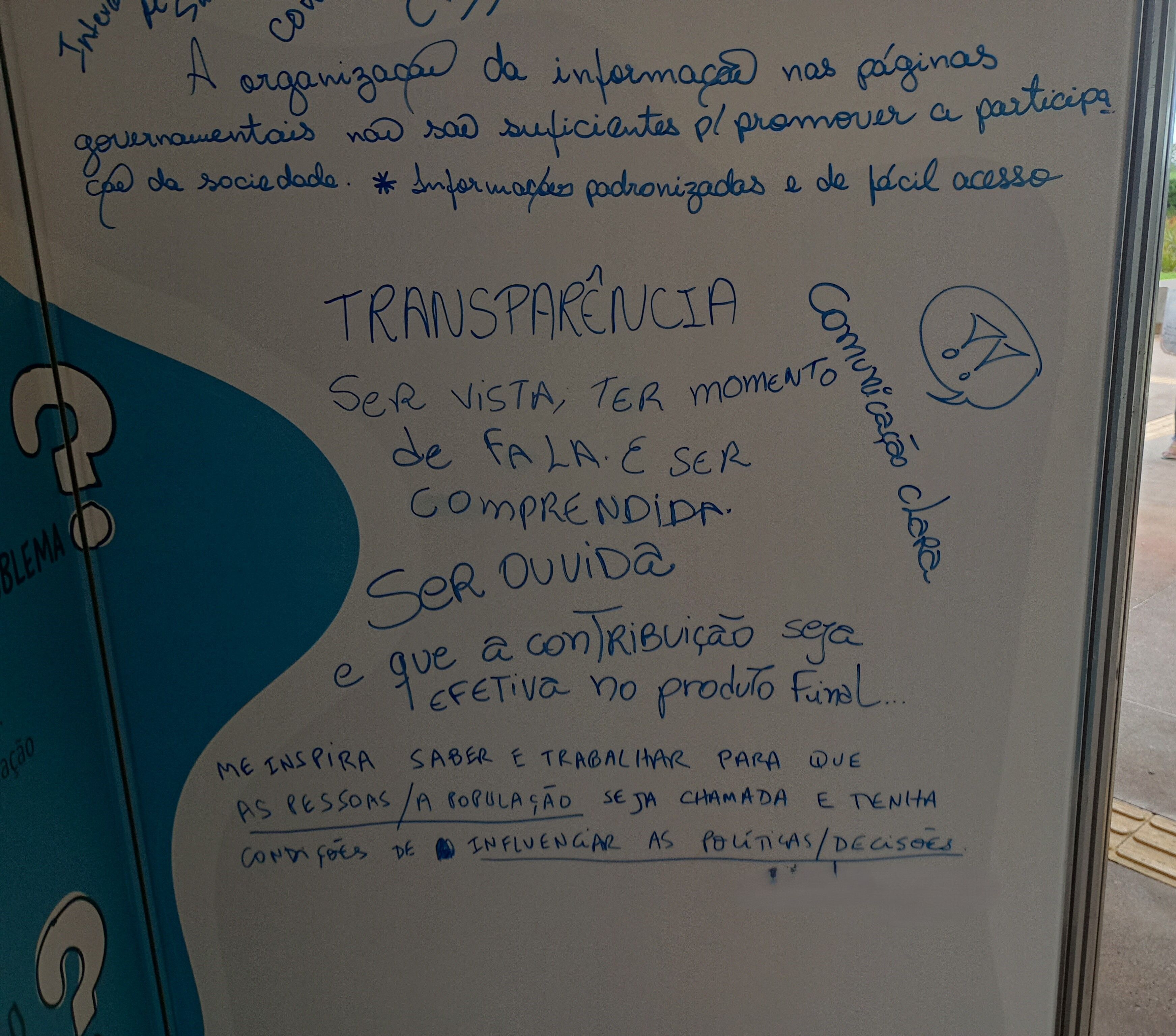

During Open America 2024, the Brazilian Office of the Comptroller General displayed a graphic facilitation of the 6th Brazilian National Action Plan in Open Government to gather hand-written contributions from participants. The one in the center of the photo reads, “Transparency: to be seen, to have the opportunity to speak and be heard, and that my contribution is included in the final output.”

Let’s consent to move beyond consent

Within the DPI debate, most data governance conversations have relied on the notion of consent. However, the limitations of the “notice and consent” model to legitimize data processing are now more than apparent, as is the phenomenon of “privacy-washing” through a focus on the legal basis for data usage “rather than whether these activities should be occurring in the first place,” as suggested by Linnet Taylor et al.

The traditional consent model emphasizes individual privacy despite the variety of actors, stakeholders, and contexts implicated by data and limits the solutions available to policymakers to mitigate the anti-democratic effects of digitalization by emphasizing individual over collective responsibility, and economic interests. It also overlooks the impacts on groups and communities, especially those that are marginalized; fails to address the structural barriers to people being equipped to manage their own data; and hinders the responsible reuse of data for innovation, diplomacy, international cooperation, and breaking down silos. Furthermore, individualized consent is particularly limited within the public sector: people cannot freely choose whether or not to use most public services.

Against this backdrop, it becomes pressing to explore people-centric approaches to data that empower individuals and communities, centering their voices in determining how their data can be used for various personal, community, and societal challenges; how to address the uneven distribution of harms and value created by data; and what gaps in the data collection leave their needs, languages, and cultures out of data-driven policies. Collective and participatory models for stewarding data can challenge corporate control and state surveillance by determining how responsibility, legitimacy, and accountability will be conceived and operationalized.

Moving beyond individualized solutions toward collectively empowering ones will also advance reflections around grievance redress mechanisms. By acknowledging power imbalances, these mechanisms, to be effective, will need to account for and enable collective action and people’s empowerment to activate them. For instance, Naomi Hossain et al. found their use to “limit collective action by individualizing grievances and their solution” in some cases, and research in India and France has shown that privileged, formally educated men are usually the ones seeking redress.

DPI and AI

As in any conversation involving data collection and usage, it was only a matter of time before artificial intelligence entered digital public infrastructure territory. And, like with DPI, this topic must advance beyond the technical layer, acknowledging structural concentrations of power and shifting the focus from the technical aspects of infrastructure to its social relevance. As highlighted by Mariana Mazzucato et al., neither infrastructures, DPIs, technology, nor data are neutral. The Dutch scandal that followed the deployment of risk profiling in the fields of social security, tax, and labor fraud ruined many lives and provided valuable lessons.

The idea that we need more data to power AI systems and that bias in datasets can be tackled turns digitalization into an end in itself and “relegates deeply rooted societal and historical injustices, nuanced power asymmetries, and structural inequalities to mere datasets” as the cognitive scientist Abeba Birhane has alerted us. “Even if one can suppose that bias in a dataset can be ‘fixed,’ what exactly are we fixing? What is the supposedly bias-free tool being applied to?”

It is also worth noting that the connections with AI are occurring in a DPI discourse that narrows its focus to e-government services, overlooks the pivotal role of private profit-driven infrastructures, and furthers itself from democratic and participatory aspirations. Additionally, companies such as Google and Microsoft have joined DPI efforts worldwide through their cloud services, with enough power to reshape infrastructures to reflect their corporate political interests – as Meta has recently shown us it is willing to do in the realm of content moderation.

Even with strides in AI-led language translation systems and advancements in linguistic inclusion, proponents of DPI would benefit from reflection on the environmental costs of AI and the rights of native speakers to govern their own language in the face of the Western companies that help to build these systems.

There are many other important conversations to have if we are to steer DPI toward the benefit of nations and to increase the potential for inclusion. 2025 will see many of these discussions evolve and will likely resolve some issues while raising new ones. Watch this space.

Authors