What is Digital Public Infrastructure? Towards More Specificity

Mila Samdub, Chand Rajendra-Nicolucci / Nov 25, 2024

Shutterstock

In 2024, Digital Public Infrastructure is a key topic of discussion and debate in tech policy circles. The term, abbreviated to “DPI,” encompasses a wide range of digital systems, from grassroots social media platforms that empower communities to state-promoted interfaces for delivering welfare payments. DPI promises a bright future for everyone, from community-minded Wikimedians to Europeans seeking to build sovereignty to global funding agencies that speak of ending poverty. For its proponents, DPI signals an aspiration for an alternative form of digitalization. DPI advocates want to see technology work differently from the commercial logic of US tech or the authoritarian commercial logic of China. At the same time, DPI advocates are practical, building real-world technological systems that reflect their aspirations for the digital world.

Over the past two years, a global consensus has developed on a basic definition of DPI. At the 2023 G20 meeting in New Delhi, global leaders committed to DPI as:

[A] set of shared digital systems that should be secure and interoperable, and can be built on open standards and specifications to deliver and provide equitable access to public and / or private services at societal scale and are governed by applicable legal frameworks and enabling rules to drive development, inclusion, innovation, trust, and competition and respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Unfortunately, that definition is so broad as to be unhelpful. In practice, different proponents of DPI advocate for different sets of solutions to different problems.

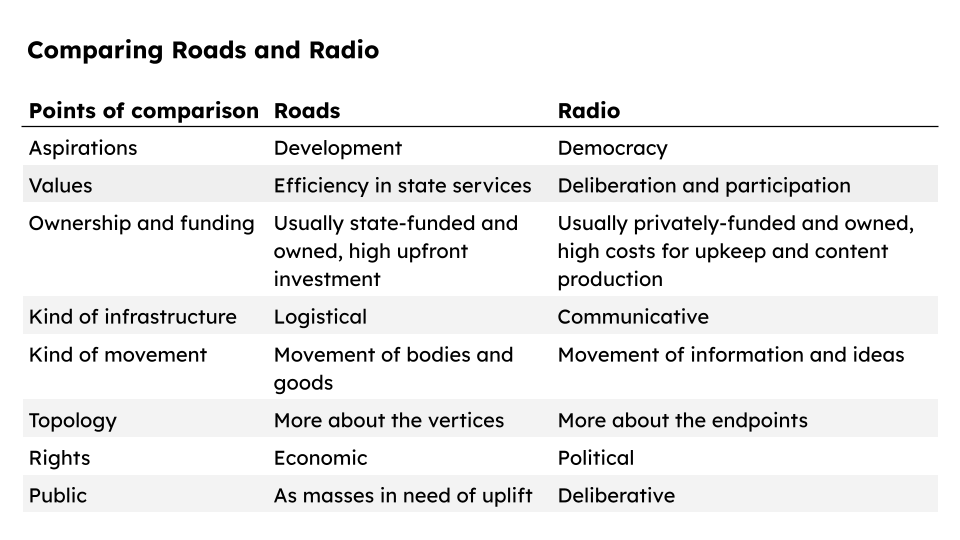

For example, though they share almost exactly the same name, the Bangalore-based Center for Digital Public Infrastructure (CDPI) and the Amherst-based Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure (iDPI) have focused on very different visions of DPI. For CDPI, and others building on the Indian experience of state-led digitalization over the past decade, DPIs are the roads of the twenty-first century, logistical infrastructures that increase efficiency and lead to development. In contrast, iDPI’s founder, US-based scholar Ethan Zuckerman, has focused on DPI as a way to strengthen the digital public sphere through communicative infrastructures that enable debate and deliberation, drawing on analogies to public radio and television. (It’s worth noting that Zuckerman, while focused on the public sphere, has consistently defined DPI more broadly and also used the metaphor of roads in his articulation of DPI.)

In the pursuit of a consensus definition, academics and policymakers alike are guilty of smoothing over these differences. The fuzziness of DPI’s definition can lead to imprecise policy with unclear goals. That confusion can obscure important choices about what visions of DPI receive resources and prioritization. For example, the “road” model’s focus on top-down identity, payments, and data systems has received most of the attention and funding globally, while the “radio” model’s participatory ethos and focus on the public sphere has been relatively ignored.

Sure, DPI can be a “shared means to many ends,” as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) put it. But with hundreds of millions of dollars in funding committed around the world, we need to be clearer about what the means and ends are. To illustrate this point, we disentangle – in stylized form – two prominent yet very different visions of DPI that we’ve briefly touched on already: DPI as roads and DPI as radio. This exercise in disambiguation is far from exhaustive. Rather, it is intended to spur further critical thinking on DPI.

DPI as roads

The website of the Gates Foundation, the world’s largest development funder and one of the institutions that is most actively promoting DPI, asks: “What is Digital Public Infrastructure?” Their answer: “DPI is like roads.” Like roads, DPIs “form a physical network essential for people to connect with each other and access a huge range of goods and services.” Deloitte claims that “DPI opens new roads for government services.” And a UNDP administrator has described DPI as being as vital for the 21st century “as railways and roads and bridges were for the 19th and 20th centuries.”

Roads enable the circulation of people and physical materials—they are logistical infrastructures of mobility. New roads can mean access to opportunities for residents of poorly-connected areas. They also enable the movement of goods to ports and factories, oiling the machinery of industry. Roads facilitate more efficient markets, enabling workers to move where wages are high and investors to invest where there is money to be made.

Roads take on a particularly aspirational character in countries undertaking ambitious projects of national development. Think of Germany’s autobahns in the 1930s, the US interstate system in the 1950s, and India’s golden quadrilateral highway system being built today. When promoters of DPI invoke roads and bridges, they are claiming the mantle of modernization, putting forth a vision of increased efficiency, productivity, and economic growth.

The road model emerges from the critical importance of development in the Global South. DPI-as-roads promises to alleviate underdevelopment by solving problems of access and efficiency. In practice, this means using digital tools to help states more efficiently provide goods and services to citizens. The paradigmatic case study is India, where, over the last 15 years, the state-promoted Aadhaar biometric identity project and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) payments system have become ubiquitous. Today, the road model reflects the Indian approach: it is composed of layers for identity, payments, and data exchanges that are promoted by the state and available for private and public use.

Yet the Indian approach should push us to consider the downsides of digital road-building. Roads have often been built for the comfort and convenience of the rich and the powerful while marginalizing and sidelining the needs of those with less money and influence. If DPIs are the roads of the digital age, we should ask what distributions of wealth and access they are facilitating. In India, where DPI was implemented top-down with minimal civil society participation, the flipside of increased access and efficiency for some has been the exclusion of the poorest members of society. And because of the public-private model used to build them, DPI systems like Aadhaar and UPI have socialized risk while privatizing profit. As the road model of DPI is promoted elsewhere around the world, these are serious problems to address.

DPI as radio

Ethan Zuckerman uses the analogy of radio to offer insights into how DPI might strengthen the public sphere. Delving into the history of public service radio, he describes what social media might look like if we could imagine beyond the bounds of today’s Big Tech model.

Zuckerman’s vision of DPI-as-radio responds to the domination of the modern public sphere by platforms like Google and Facebook. It is a proposal for a more diverse, deliberative, and decentralized digital public sphere. Radio’s history of public service media serves as an inspiration for responding to market failures in today’s public sphere. The BBC and NPR provided alternatives to commercial radio that improved the public sphere as a whole, filling gaps and leading by example. The primary goal of DPI-as-radio is building information infrastructures that have a vision of the public good at their core, not profit or entertainment, providing a counterweight and alternative to the big tech platforms.

While this model is appealing, especially to liberals, it raises a number of questions. Whose vision of the good? In an age of mistrust, can government-funded (or run) information institutions flourish? Did public service media work in the past because options were limited, quite literally, by finite broadcast spectrum? In the abundance of the digital environment, do people really need public service media or are these solutions in search of a problem?

Towards a more concrete conversation

Multiple visions of DPI are circulating today: DPI-as-roads and DPI-as-radio, as well as other variations that don’t map quite so readily onto a single metaphor, including an ongoing European push for DPI as systems to support regional sovereignty. Yet in global fora like the G20 and the UN, these different proposals are being lumped together and discussed in the same breath, even when they may have little in common.

To make successful policy, it’s important to untangle what vision of DPI is being advanced, what assumptions and limitations are along for the ride, what problems are trying to be solved, and how the model tries to solve them. In cases where multiple models are being advanced, it may emerge that they are not compatible with each other (e.g., on questions of scale, participation, and centralization). Or it may emerge that different visions of DPI hold lessons for each other. For example, technologies of public distribution (“roads”) would benefit from incorporating the radio model’s participatory ethos, complementing access with accountability.

Policymakers, researchers, and technologists would do well to account for these distinctions. Ignoring them risks repeating old mistakes and missing the full picture of how to best harness DPI in the many different contexts in which these systems are applied.

Related reading

Authors