Underexplored Ways to Regulate Social Media

Nathaniel Lubin, Kalie Mayberry, Manon Revel, Luke Thorburn / Aug 28, 2024

A footbridge in the wilderness.

In early July, the US Supreme Court returned cases involving content moderation laws passed in Texas and Florida to lower courts, asserting that “[the] government may not, in supposed pursuit of better expressive balance, alter a private speaker’s own editorial choices about the mix of speech it wants to convey.” In rejecting viewpoint-based policymaking while remaining open to alternative means for regulation, the Court added another thread to the complex web of potential social media regulation. These include antitrust enforcements by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and suits by the Department of Justice (DOJ), a federal law that could result in a TikTok ban, proposals to provide protections for kids, new state laws giving expanded rights to parents, and design codes (among many other proposals).

In a recently published peer-reviewed study, we sought to make sense of the varied potential interventions by organizing and visualizing interventions within two distinct “maps,” viewing social media either as an architecture or as a market. Without arguing for a specific intervention, the analysis shows how the priorities of regulators – understood as the harms they seek to minimize – can reveal specific leverage points for intervention. Though each map theoretically transposes onto the other, the paper argues that interventions are much easier in practice when identifying the most efficient mechanism.

In this article, we go a step further: using the maps and prior analysis of how existing proposals fit within the picture, we identify the most under-explored approaches for intervention. Through that lens, we argue that three categories of intervention have been systematically under-regulated as product features: (1) account creation; (2) user interfaces; and (3) recommender systems. We further claim that three categories of intervention have been systematically under-regulated as markets: (1) taxes (and subsidies); (2) competition requirements; and (3) direct provision by the government (i.e. direct purchasing of goods and services).

We briefly consider each here, with a primary focus on interventions within the context of the United States.

Social Media as Architecture

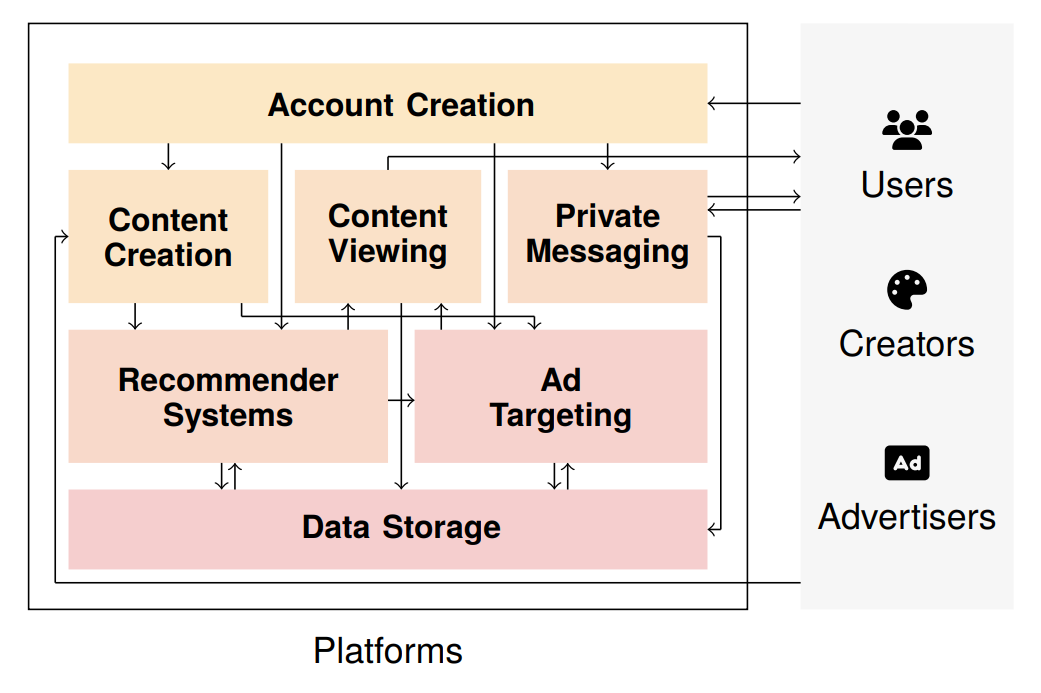

Social media platforms can be viewed as a set of interacting components, usually including systems for creating accounts, producing content (both organic content and advertisements), recommending content, viewing content, targeting ads, private messaging, and storing data. The design of these technologies determines what actions are available to users and other stakeholders and the relative effort required to perform these actions, and so by regulating design it is possible to impact the effect that social media has on the world.

Social media as a set of features or affordances. Note that this is a general (but necessarily incomplete) framework – for specific platforms, some components are more or less relevant.

See the paper for a more comprehensive table with specific examples of each regulatory approach.

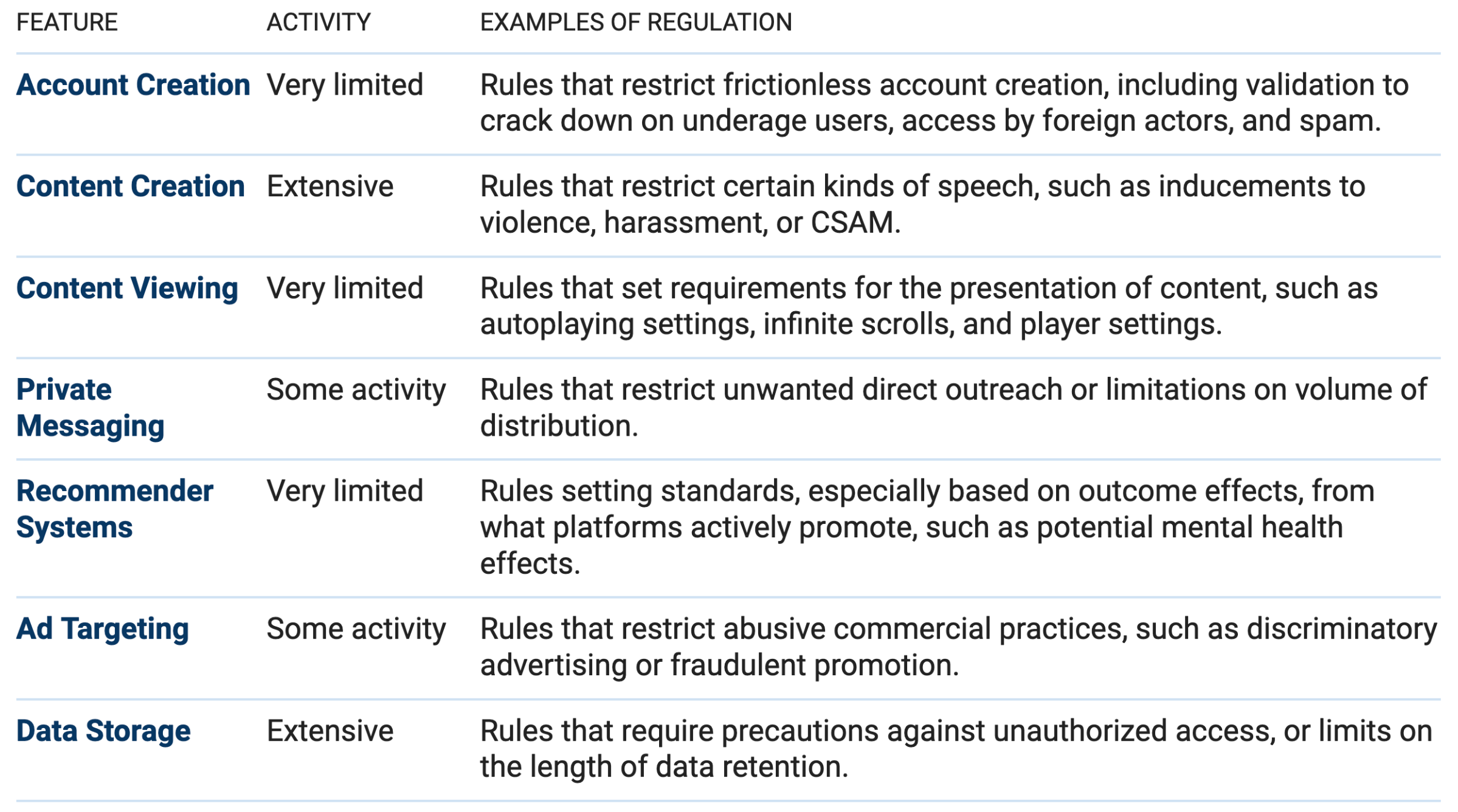

Our goal here is to highlight that proposed rules – at least until quite recently – have focused on a narrow set of product components. These include traditional business areas, like advertising and data storage, as well as particularly-contested rules governing content creation. Content creation restrictions must contend not only with Section 230 but also First Amendment protections more broadly; advertising and data storage rules emerge more directly from existing commercial rules.

By contrast, a range of design features have barely been engaged with by regulators, even if they are central considerations for product designers and engineers. The goal of these approaches generally would not be the architecture features themselves, but instead the effects of those features, similarly to how regulators evaluate and set standards for physical goods and services (e.g. safety standards for cars or pharmaceutical products). Based on our analysis of the architecture map, we believe there are three specific areas of opportunity:

- Access to harmful material by minors is a hot political topic – and has generated state laws granting expanded parental oversight rules among other directions. There are a wide range of other potential interventions, however, related to account creation – such as device-level age verification, or higher-bar requirements for proof of legitimacy (even if public activity is anonymous). Such rules would have profound effects not just on fears around underage users, but also activity for foreign adversaries, and the increasing risk of by scammers and fraudulent behavior at scale on platforms (such as elder abuse).

- Second, independent of the content itself, the user interface for content viewing is also important, speaking to potentially-harmful design practices which prioritize growth and excessive use (e.g. via autoplay settings). While such rules engage directly with the First Amendment rights of companies (who argue that all coding and design is speech), there is opportunity to differentiate between system architecture and speech itself, at least if conditioned on a harm-minimization framework where there are tradeoffs.

- Lastly, recommender systems regulations also have not been passed by regulators in the US outside of the Texas and Florida laws. New proposals, such as Minnesota’s proposed design bill, or other methods to add non-engagement signals to recommendation systems are important for expanded activity. Potential interventions include new standards for the effects of active promotion on outcomes like mental health, interventions that would likely induce planforms to expand non-engagement user signals (e.g. user feedback on what content that they affirmatively say they want more of irrespective of their behavior) and expanded user controls for what product features they experience.

If pursued, each of these approaches would be contested, and subject to pushback from technology companies used to minimal regulatory interventions. Nonetheless, we believe exploring new opportunities could contribute to lowering the temperature on social media platforms by reorienting attention away from speech towards baseline standards for experience.

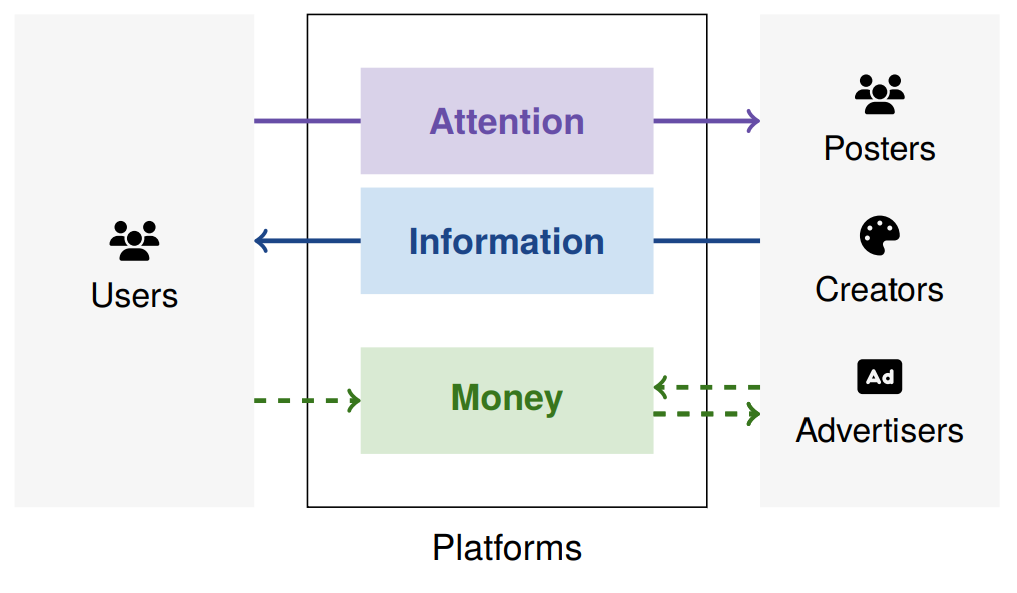

Social Media as Market

Alternately, social media can be viewed as a market in which attention, information, and money are exchanged. In this model, platforms act as market makers or brokers, negative effects of social media (including externalities) are market failures, and regulations are market interventions to correct for those failures.

Social media as a broker for attention, information, and money. Note that this is a general (but necessarily incomplete) framework – for specific platforms, some parts are more or less relevant.

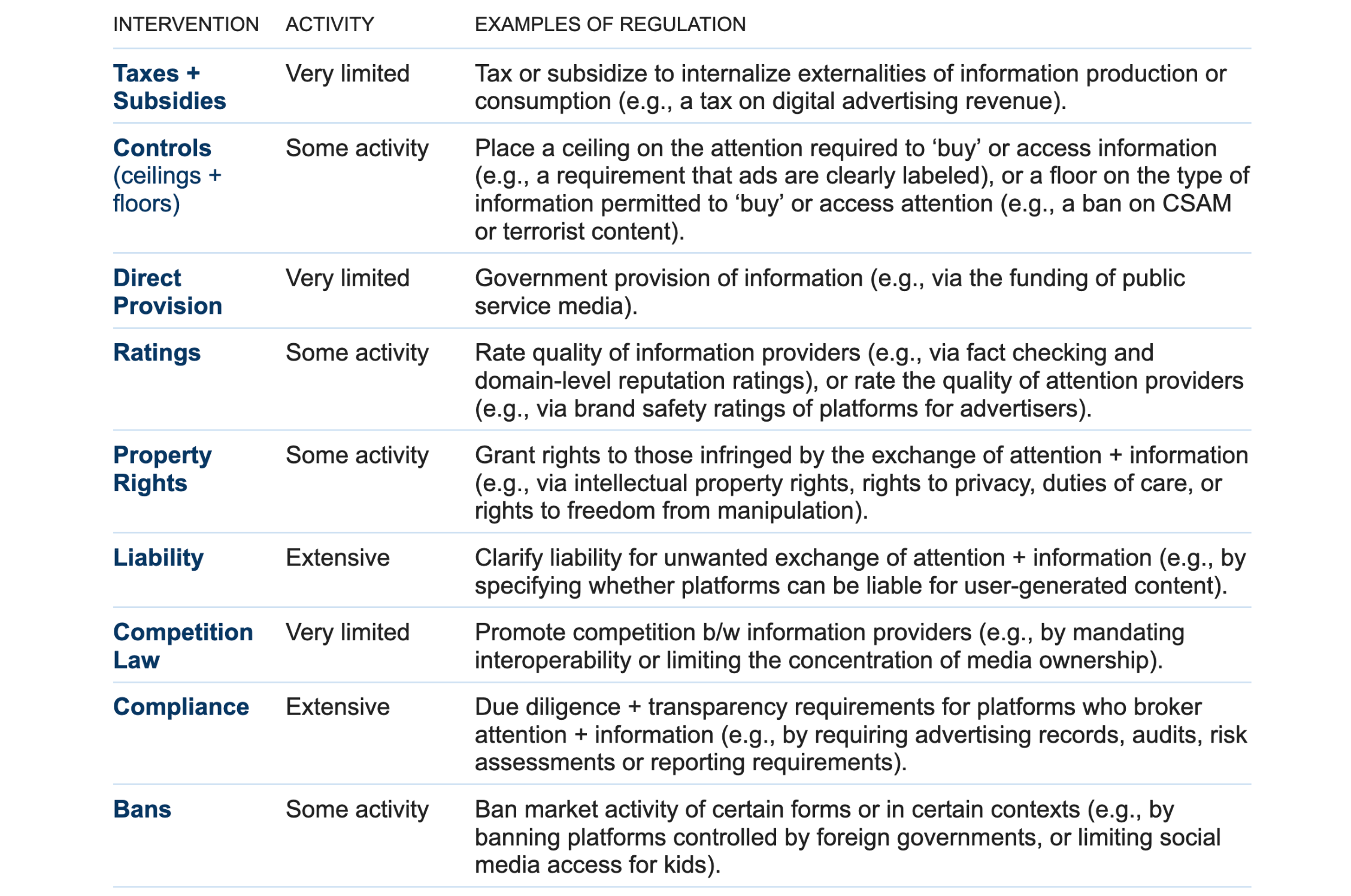

There are standard ways a regulator can intervene to correct for market failures — such as taxes, price controls, and property rights — and while social media regulation is not often framed in economic terms, we can see that many approaches to regulating social media correspond to these categories of market intervention (in the market described above).

See the paper for a more comprehensive table with specific examples of each regulatory approach.

We emphasize that here we are talking about the market which is social media (in which the objects of exchange are attention, information, and money), not the market for social media apps.

In this breakdown, most regulatory activity has been in the form of compliance measures (particularly the extensive data access, record keeping, audit, and risk assessments required by Europe’s Digital Services Act), property rights (including rights to privacy under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, and the “right to be forgotten,” which is the right to have data about you erased), and liability (particularly Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act in the US).

By contrast, some forms of market intervention have received relatively little regulatory attention, and arguably merit further exploration.

- First, taxes and subsidies are perhaps the textbook approach to correct externalities, but in the social media context have received little attention. In part, this might be due to the difficulties of quantifying the impacts of social media reliably enough to form the basis of a Pigouvian tax or subsidy — there is substantial scientific uncertainty over the degree to which a given platform causes (say) affective polarization, or poor mental health. However, there are approaches to taxation which don’t require such causal estimates. Taxes could target platforms in general, or digital advertising revenue specifically, as has been proposed in two recent California state bills. The revenue raised by these taxes could then be used to fund local journalism and mental health services.

- Second, current platforms benefit from network effects and high switching costs, meaning that users are effectively forced to use particular platforms if they want to stay connected to their communities. This dynamic undermines competitive innovation. Various forms of competition law, particularly related to mandates for interoperability, middleware, and data portability, seem firmly in the public interest but have received little attention from regulators. In the US context, three concrete proposals include updating government procurement rules to require that companies are only eligible to receive public funds if their products mean certain standards of interoperability, updating state-level contract law to make unenforceable clauses that prevent the reverse engineering of a product in the name of interoperability, and creating an “Interoperator’s Defense,” which would provide a legal safe harbor to those who engage in adversarial interoperability in pursuit of legitimate user interests like privacy and accessibility.

- Third, while many governments cannot legally influence the speech of others, they are free to produce their own speech. Such direct provision of information is already widespread in the form of public service media (think PBS or the BBC), weather forecasts (NOAA), public health advice (healthcare.gov) or emergency information (FEMA), though in many cases, and particular in its more journalistic forms, is relatively underfunded in the US. If the appropriate response to bad speech is more speech, governments could increase funding for public service media organizations, ensuring they have an engaging online presence. While public media is not always widely trusted, there is increasing research and experimentation with ways to improve the trustworthiness of news, including with participatory forms of journalism, that might provide a model that is broadly valued.

Looking Ahead

We have focused here on the US where — whatever the outcome of the coming presidential election — social media regulation will remain a contested issue. The frameworks we provide illustrate the need for the debate to shift from partisan approaches towards baseline standards of freedom, self-determination, and more efficient markets. To that end, we believe there are opportunities for regulators to dive deeper into less-emphasized areas for intervention, avoiding topics like speech regulation in lieu of product safety whether implemented via market interventions or design regulations.

At the federal level, recent regulatory attention has focused on market interventions such as increasing liability for platforms if they do not shield minors from inappropriate content (the Kids Online Safety Act, KOSA, which passed the Senate in July along with an update to the Child Online Privacy Protection Act) and enshrining rights to privacy (the American Privacy Rights Act, APRA). There has been greater exploration of regulatory approaches at the state level, including taxes and some design-based regulations. For its part, the EU (which we address more thoroughly in the study) is working through the implementation of the Digital Services Act, an omnibus law that contains elements from both the market and architecture regulatory paradigms. The two frameworks described here provide a way to map these different approaches and reason about which will be most effective.

Luke Thorburn was supported in part by UK Research and Innovation [grant number EP/S023356/1], in the UKRI Centre for Doctoral Training in Safe and Trusted Artificial Intelligence (safeandtrustedai.org), King’s College London.

Authors