Three Pillars of Human Discourse (and How Social Media Middleware Can Support All Three)

Richard Reisman / Oct 24, 2024Richard Reisman is a non-resident senior fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation, a contributing author to the Centre for International Governance Innovation’s Freedom of Thought Project, and a frequent contributor to Tech Policy Press.

When we talk about the dilemmas relating to governance of public discourse as it plays out on social media, we often focus on human agency. This is true both when we characterize what’s wrong — we often say that users don’t have enough control over the speech they interact with online — and when we propose solutions, which often focus on giving users greater agency over the content, algorithms, and platforms with which they interact.

Agency is essential, but I suggest that by placing too narrow an emphasis on agency, we are neglecting other fundamental pillars that support a thriving public sphere: mediation and reputation. If agency is the ability to choose, mediation is the social process that ensures you have good options to choose from, and reputation is the shared knowledge about which options are good. All three of these pillars exist in rich forms in offline networks, but mediation and reputation are comparatively neglected in the design of social media. The need for all three pillars becomes clear if we seek insights from offline discourse to improve how we steward it online.

Consider proposals for social media “middleware,” under which users would be able to choose from a marketplace of third-party algorithms that determine how content is ranked on the platforms they use. An influential proposal from 2020 positioned middleware as a remedy that would both give more agency to users and reduce the risk of power (closely related to agency) over public discourse accruing in the hands of a small number of private platforms. Important as that is, a sole focus on agency understates the broader potential of middleware, which could also help enrich important online processes of mediation and reputation-building.

This piece reviews how discourse is a social process, introduces the three pillars of agency, mediation, and reputation on which it depends, and describes a systems view of how these pillars synergize and complement the limitations of each. It then uses this framework to make an expanded case for middleware, arguing that the social media paradigm of closed platforms cannot adequately support these pillars but that middleware (among other forms of interoperability) has the potential to do so. Applied to all three pillars, middleware can support the restoration of the emergent social processes that shape discourse to serve conflicting rights in win-win ways. This can cut through the speech governance dilemmas that now lead to controversy and gridlock – and support democracy against threats of authoritarianism or tyranny of the majority.

Discourse is social

Instead of starting from symptoms – the harms and threats related to current social media and how they are used – and the remedies currently being attempted by platforms and policymakers, it is necessary to go back to basics to understand the underlying disease. As Marshall McLuhan emphasized, human society co-evolves with its communications media tools. From speech, to writing, to the press, and on to mass media, discourse has become more open and free. Each major jump in media tools has been disruptive, but open societies have learned (slowly and in spite of local and temporary failures) to collectively manage that disruption to steer between chaos and tyranny. That is generally not a matter of tight control over expression but of organic mediation systems that support our natural social nature and resilience. Humans have evolved and flourished through our adaptive blending of independent thinking, collective intelligence, and teamwork.

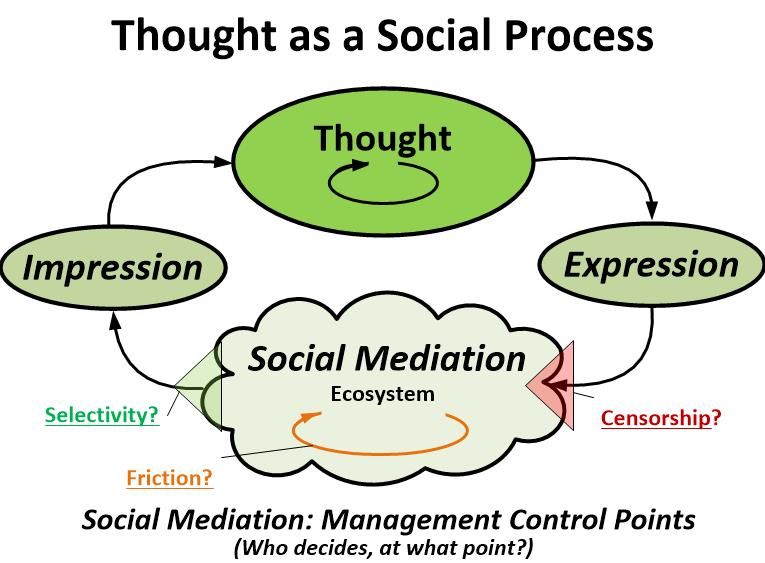

Most fundamentally, this requires understanding that thought is a social process, as illustrated in this cyclic diagram. Thought leads to expression, but then that expression is processed through social mediation by other individuals and groups, then comes back to us as impression on our senses, which leads to further thought. The problems we face with social media relate not so much to too much or too little freedom of expression, but to too little freedom of impression to filter any abusive flow of expression. The US First Amendment has been successful in enshrining strong freedom of expression because it also provides strong freedom to choose what to listen to.

Figure 1: Thought as a Social Process (Reisman)

From this perspective, it becomes apparent that social media work like an acceleration of the multi-stage word-of-mouth propagation of rumors, not the single-stage, one-to-many broadcasting of mass media. Controls on expression necessitated by the scarcity and reach of mass media channels was a temporary aberration. Traditionally, open societies were permissive of word-of-mouth expression but managed propagation and impression through soft norms of community contexts, and informal feedback and reputations within those communities. That fed back to our individual agency as we learned to moderate our speech so that others would listen and pay heed to us. Social media platforms have disintermediated that process and taken control of the feeds they impress on us. Instead of human social mediation based on individual and community values, they have substituted centrally-controlled algorithms that have collapsed the context and judgments of speaker, listener, and community that people have relied on to self-moderate.

A metaphorical reminder of our interdependence in thought as a social process is the Jewel Net of Indra (adapted, drawing on Stephen Mitchell and other sources):

Imagine an infinite net. At each crossing point there is a jewel. Each jewel is multifaceted, reflecting all the other jewels. Each jewel represents an individual being, a consciousness, a cell, an atom – or even a group. Every jewel is intimately connected with every other. A change in one means a change, however slight, in every other.

Human discourse is a process that works through expression to, and impression from, this jewel net. Current social media platforms have ignored the humanity of this jewel-net, and their filtering of what is fed to us substitutes their own context-collapsed algorithmic simulacrum of the jewel-net’s human richness.

Three Pillars

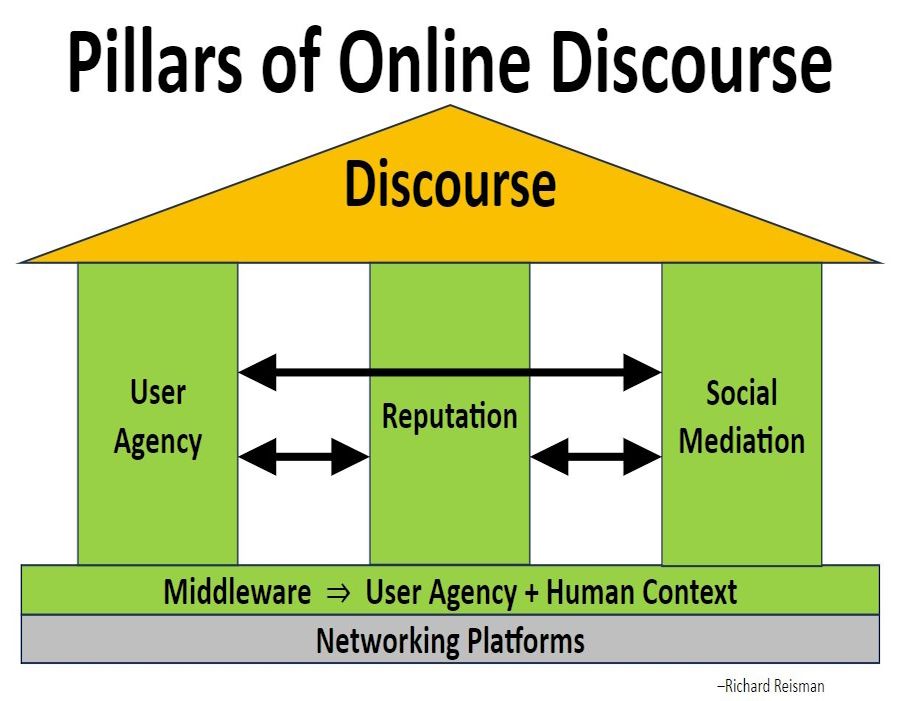

Turn back to the fundamentals of discourse – as it has been in traditional society, and how it must be in the digital era if democracy is to be sustained. Consider this high-level architecture diagram. The underlying layer of networking platforms provides basic messaging connections, but middleware provides a level of open interoperation that, in turn, supports other services, most importantly the three pillars. Those pillars, in turn, support healthy discourse.

Figure 2: Pillars of Online Discourse (Reisman)

Agency

Individual agency is the process need that currently motivates most middleware efforts.

- Definition: Freedom and ability to choose what messages you hear, think about, and say – and what groups to associate with. It is a process of individual decision-making that supports freedom of impression, freedom of thought, freedom of expression, and freedom of association/assembly.

- Relation to context: Agency gives users and their agents and associations the ability to freely seek, interpret, and add (or remove) context.

Mediation

Social mediation is the process needed to support message flow, keep abuses of agency in context, and generate “social trust.” That process emerges from an organically structured social mediation ecosystem.

- Definition: Collaboration that improves the quality of what messages you hear and how you hear them because they have been propagated through chosen social networks of other humans (and their organizational or technological agents) – each of which selectively filters, reconsiders, and re-articulates. It is a collaborative process of judgment and influence about ongoing message flows with varying degrees of structure.

- Relation to agency: A collaborative process driven by one’s own agency in expression and impression and by association with other individuals and groups one chooses to communicate with and participate in. It leads to having good and diverse options to choose from, along with shared context on why.

- Relation to context: Mediation, when applied well, adds context by bringing in more viewpoints (augmenting the message with reactions, comments, annotations, etc.) and increases the chances that appropriate perspectives on context are communicated.

Reputation

Reputation is the quality of trustworthiness that is learned through those processes and feeds back to help guide both individual agency and social mediation.

- Definition: Knowledge about the degree to which you can trust the messages of different agents. It can be tied to both items and people; e.g., a book can have a reputation. It can also be specific to a subject domain or community. A quality, as distilled at any given point in time from the process history of individual and group judgments.

- Relation to agency: Qualitative guidance from oneself and others, on which choices have proven to be good – in the broad sense, and especially trustworthy.

- Relation to context: Reputation is an important qualitative aspect of context. Not all likes, shares, comments, etc., are equal in value, and other signals of reputation are also important.

A Systems View

The pillars complement and reinforce each other. Each, on its own, has limitations, which entail the kind of often-raised concerns summarized here:

- Agency concerns:

- Polarization, fragmentation (affective, antagonistic)

- Poor choices (filter bubbles, echo chambers, extremism)

- Mediation concerns:

- Paternalism, authoritarianism, tyranny-of-the-majority (“platform law”)

- Homogeneity (closed and narrow-mindedness)

- Reputation concerns:

- Gaming the system (“confidence games”)

- Unreliable raters and questions of legitimacy/authority

- Privacy exposures (personal data and behaviors)

But the pillars complement each other in ways that mitigate these risks, thus countering those concerns, as outlined here:

- Agency ⇿ Mediation synergies

- Agency mitigates risks of paternalism, authoritarianism or tyranny of the majority by decentralizing power and limiting the influence of any single agent (or majority) in the network.

- Mediation mitigates risks of polarizing fragmentation and poor choices by increasing the quality of the most salient choices offered, and the context for evaluating that.

- Agency ⇿ Reputation synergies

- Agency mitigates risks of gaming or unreliable raters by giving people the option to choose between alternative reputational systems or signals and seek those that are more reliable.

- Reputation mitigates risks of polarizing fragmentation and poor choices by creating a tendency for people to preferentially listen to high-reputation sources and speak in ways that earn and preserve reputation.

- Reputation ⇿ Mediation synergies

- Reputation mitigates risks of paternalism or authoritarianism by discouraging people from attending to overly paternalistic or authoritarian agents and the risk of extremism by factoring in diverse sources of reputation.

- Mediation mitigates risks of gaming or unreliable raters by making it more difficult for false reputational information to flow through the network or be boosted by raw but narrow popularity.

An expanded case for middleware

Middleware has emerged as a way to cut through these dilemmas. It has gained increasing support as a way to limit the unaccountable power of private global platform businesses and to restore human agency. Middleware is a technology that can directly help

- restore user agency to its rightful place in the flow of discourse, and

- balance unaccountable platform power.

The broader benefits are achieved indirectly. Middleware does not itself solve these problems; rather, it provides a flexible foundation for tools that enable people and their communities to solve them. It is people and communities, not technology, that are needed to bridge divides and transform conflict. Middleware, in itself, cannot do that, but it can help enable human-driven tools to do that.

It may seem hard to imagine how technology can restore the nuance of this human network. But consider the app store analogy. App stores, as pioneered by Apple, then adopted by Google and others, are a kind of middleware for our devices. They add a layer of function and control that rides on the platform provided by Apple or Google or others to create an open market of independent software and service providers (under more or less limited platform control). When the iPhone launched in 2007, it had only about a dozen apps all developed by or under contract by Apple. By 2008, Steve Jobs saw the demand from both users and app developers and opened the App Store with some 500 third-party apps. This relatively simple technology combined with some basic administrative services to catalyze an entirely new and largely open ecosystem that fueled amazing growth and innovation far beyond anyone’s expectations – the “App Economy.”

Much as social media middleware can act as a user agent “app” to multi-home and interconnect separate social media platforms, many common apps on both Apple and Google Android create dual-linked ecosystems that further multiply the total value. And while current conceptions of social media middleware are relatively basic, this app store analogy shows how a distributed system with modular components can seem simple and seamless to users, but mature into a complex structure of many layers that remain largely hidden. Many common apps interoperate seamlessly with one another and other complex back-end web services: travel apps link independent airlines, hotels, car rentals, payments, and tours; shopping apps link independent search, reviews, purchase, payment, delivery, and tracking; streaming apps link smart TV and audio devices with independent program libraries on Netflix, Disney, HBO, and many more. It was barely imaginable in 2008 that industry ecosystems could self-organize to interoperate in this way, and that such complex services could become available and usable on pocket phones within a decade. But if the demand is there, the market can develop to meet it.

The idea of social media middleware has mostly emerged over the past decade as a response to widespread feelings of lost agency as platforms began to dominate the formerly open web. Impetus has come from Mike Masnick, a Stanford Working Group led by Francis Fukuyama, and a new class of decentralized social media systems, beginning with the fediverse of Mastodon and the embrace of middleware to create an open market of feeds by Bluesky.

But while many have come to see middleware as opening a new chapter in user control and agency, along with limits on platform power (over both markets of ideas and economic markets), others fear that high levels of user control and agency will lead to chaos and fragmentation. Many alternative remedies to the ills of social media have been advocated, such as bridging systems that might work within centralized platforms to bridge divides and transform conflict – and middleware is sometimes seen as incompatible, or even counter to, such alternatives. But, from the broader perspective of the three pillars, middleware can be seen as an enabling technology for more open experimentation and adoption of many such remedies. It can also support shared development and operation of common solutions across many platforms and communities.

Platforms cannot adequately support the pillars…

Consider the pillars from the perspective of the issues we face now – without middleware:

- Agency: There seems no way out from the lack of incentives and of innovative entrepreneurship to support rich affordances tailored to diverse user segments. And in terms of the deeper issues of democracy, the “loaded weapon on the table” metaphor persists, as a risk of platform or government threats to democracy – even if there were more platform-provided affordances for user control.

- Mediation: Large, centralized, ad-supported platforms are incentivized to build affordances for information propagation that systematically surface fads and sensationalism / low-quality information (e.g., engagement optimization). They lack incentives and resources to provide robust mediation support for communities that fully address diverse needs.

- Reputation: Large, centralized, ad-supported platforms are incentivized to optimize for engagement, regardless of (the speakers’) reputation for truth and wisdom. They are poorly incentivized to develop reputation systems tailored to sub-communities.

But middleware can…

Consider how the pillars can reinforce one another – when enabled by middleware:

- Agency: Full restoration of agency is hard for both platforms and users (can be complex and burdensome). Middleware allows people to delegate their agency to trusted agent services that suit their preferences at whatever granularity of control (vs. simplicity) they desire.

- Mediation: Middleware services can effectively act as community-centered agents in the network, preferentially surfacing and propagating information that is high-quality and valued by the social groups they are designed and chosen to serve.

- Reputation: Middleware services that make effective use of reputational information (both explicit and implicit) will better serve their users. They can specialize in specific communities and domains (like “science Twitter” and "medical Twitter”).

(For additional background, see this on social mediation processes and ecosystems, and this vision of how they might be reconstructed in digital form, as well as this earlier working presentation of some of these ideas. That earlier working presentation also touches on how these pillars also apply to the development of AI, as will be addressed further in a future piece.)

Looking ahead

There is already growing support for social media middleware, with its current focus on the one pillar of user agency and how it limits platform power – both in the policy world and in initial implementations like Bluesky that may grow and broaden organically. However, there remains continuing skepticism among many in the policy world and risk that the current momentum of Bluesky and others may fail to reach critical mass and find sustainable business models. Broadening the vision to all three pillars offers the potential to reduce concerns, draw in much wider support, and demonstrate additional successes.

This paper suggests why all three pillars are essential to healthy discourse and why the lack of attention to them has harmed current social media. Middleware can also help to:

- organically maximize rights to expression, impression, and association in win-win ways,

- cut through speech governance dilemmas that lead to controversy and gridlock, and

- support democracy and protect against authoritarianism or tyranny of the majority.

Without the strengthening and mutual reinforcement of all three pillars and the enablement of open innovation and interoperation that middleware affords, social media will almost certainly continue to struggle to find a healthy path between chaos and tyranny. That is an existential threat to democracy and human flourishing. Re-establishing these pillars effectively will be a long and difficult task, with a variety of complex issues to resolve. But no other path seems likely to be found – or to be navigable – for long.

Acknowledgements: The author extends special thanks to Luke Thorburn for his invaluable suggestions on refining these ideas and how to organize and present them. He also extends thanks to the many experts who have provided encouragement and helpful feedback on earlier presentations of this 'pillars' framing over the past year.

Authors