The UN’s Global Dialogue on AI Must Give Citizens a Real Seat at the Table

Tim Davies, Anna Colom / Oct 2, 2025

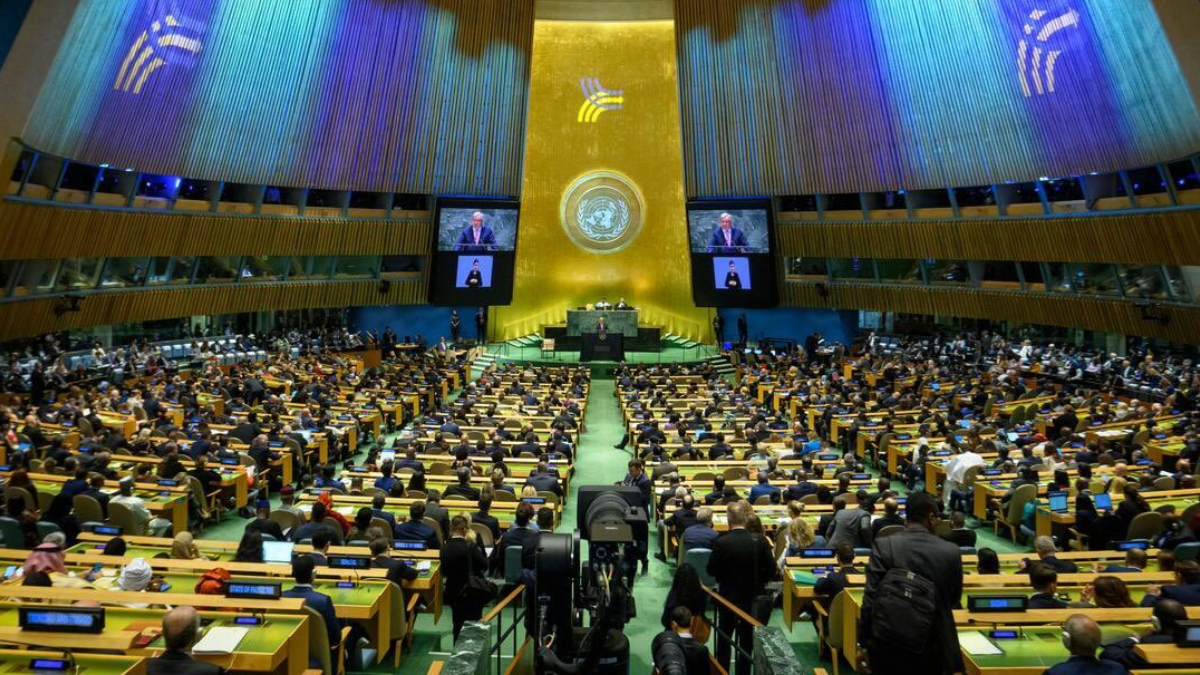

The Global Digital Compact was adopted by the UN General Assembly in New York City on September 23rd, 2024. Source

In an annual calendar packed full of global AI conferences and summits, the new United Nations Global Dialogue on AI Governance scheduled for Geneva next July is entering a crowded field. Yet, this Dialogue and its accompanying Scientific Panel, formally launched last week by the President of the UN General Assembly (UNGA), have the opportunity to bring something unique to the table: the voice of citizens.

Learning from decades of global convening on climate change, these new tools of AI Governance must place local lived experiences at their heart. Unless they can meaningfully centre the voices of citizens, they risk irrelevance before they get started.

To date, global discussions on AI, regardless of the countries involved, have remained stubbornly dominated by a limited set of voices and predominantly technical framing: ignoring everyday realities of people encountering effects of AI in their communities, workplaces, schools and environments across the world. Underpaid workers developing AI systems and products; patients and doctors in healthcare systems benefiting from AI-driven treatments; residents in drought-affected communities hosting new data centres; and educators and students exploring new AI tools for learning are all amongst those whose perspectives should be informing the evidence base and agenda setting for the new AI governance global dialogue.

The model of an Independent International Scientific Panel and an annual convening follows a template from the climate sector where the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference and Conference of the Parties (COP) draws heavily on the work of the scientific Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In recent years, experiments with direct citizen input into COP have gained pace, and at COP30 in Brazil in a few weeks, the need for a standing ‘citizens-track’ within the summits will be firmly on the table. The AI governance field should reflect on experiences from 30 years of climate action: without listening to and involving as partners and co-creators of action the people and organizations with lived experience of the issue at hand, international Summits may once again fail to deliver change.

Two key actions can make sure that this new UN architecture for AI governance is able to listen and deliver change. Firstly, the Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence must incorporate, within its remit and among its members, a focus on the social and environmental impacts of artificial intelligence and on public attitudes to AI. Second, there must be a robust standing mechanism to ensure public voices are directly present within the meetings of the Global Dialogue on AI Governance. These are both achievable ends.

In remarks at the launch of the High-level Multi-Stakeholder Informal Meeting to Launch the Global Dialogue, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said that the Global Dialogue on AI Governance is “the world’s principal venue for collective focus on this transformative technology.” AI is a socio-technological phenomenon: to govern it, we have to understand how people and societies are experiencing and responding to it. Democratic governance is about power distribution in how decisions are made, meaning these diverse voices need to be part of the decision-making process.

Over recent years, a wealth of research has emerged on public attitudes towards aspects of AI. Academics, governments, industry and civic start-ups have undertaken numerous surveys, studies and public deliberations. However, to turn these collected insights into actionable evidence for global policy requires both curation and critical evaluation. The Public Voices in AI project recently conducted an evidence review of over 320 individual examples of international evidence on people's perceptions of AI, revealing a mixed picture regarding evidence quality and specific gaps in the analysis of how AI affects marginalized groups.

By including a focus on evidence of public impacts and attitudes towards AI, the Scientific Panel could invite submission of relevant research, identify, track and report on robust findings, and catalyse work to fill gaps in the coverage and quality of insight into how AI is impacting different global publics. Doing this effectively will rely on ensuring the Panel includes and draws on a wide range of expertise, including relevant social science perspectives, knowledge based on the lived experiences of AI systems, as well as evidence from civil society groups that tap into diverse experiences with AI. As General Assembly members appoint panel members, they must go beyond ‘usual suspect’ nominees and consider how their chosen experts represent the realities and demands of their residents and civil society.

The second priority: a standing mechanism to bring citizen voices directly into an intergovernmental, or multi-stakeholder, global dialogue might seem like a daunting prospect. How can the experiences and insights from a student, farmer, teacher, truck-driver, or grandparent living far from Geneva or New York be heard effectively in the committee rooms and conference halls of a global summit? How do we steward localism in a global setting? Fortunately, there are tried and tested options. The report Global Citizen Deliberation on Artificial Intelligence: Options and design considerations set out last year five different approaches to engaging with citizens across the world at scale: from using collective intelligence tools and hosting distributed dialogues feeding into global processes, to carrying out a citizens review of global meetings and bringing citizen rapporteurs directly into the rooms where discussions are taking place. The deliberation field has demonstrated that, with the right facilitation and support, citizens from any background can quickly get up to speed and articulate meaningful views on the future of AI that ground, motivate and enrich debates.

Over the past year, tech firms and civic start-ups have recognized the value of soliciting deliberative global input. In the coming months, Stanford’s Deliberative Democracy Lab will host a first cross-industry online dialogue, engaging thousands of participants from the US and India in live small-group conversations and polling to explore attitudes towards AI Agents. The Collective Intelligence Project’s Global AI Dialogues regularly report on attitudes towards AI, gathering input from citizens in over 70 countries. These experiments point to the potential for industry to play a role in funding and supporting citizen inputs to the Global Dialogue, but also the risk of cooption.

It is increasingly common to see reports on AI pay lip service to the idea that our collective future alongside AI must be determined through public engagement. Indeed, without engaging the public, trust both in AI and in the governance responses to it is likely to falter. It will not be easy, yet we need to move from talk to action: to genuinely provide a seat at the table for public participants, moving from performative consultations to shared decision-making, and to secure a Scientific Panel and Global Dialogue that ensures diverse public voices are driving both debate and engaged in action.

Authors