The Most Critical Resilience Questions of Them All: Taiwan’s Undersea Cables

Charles Mok, Dr. Kenny Huang / Sep 19, 2024

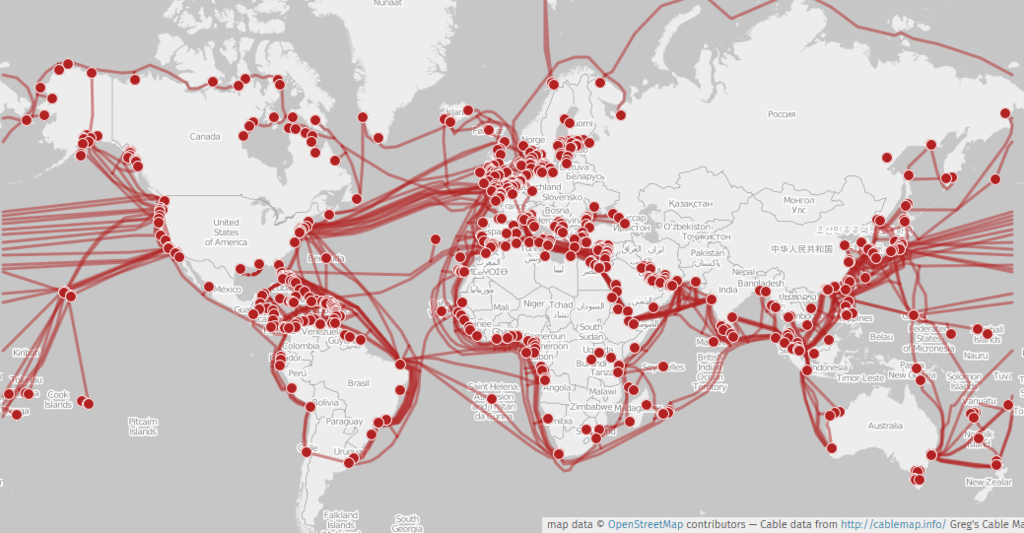

Cable data by Greg Mahlknecht, map by Openstreetmap, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

This article summarizes the paper “Strengthening Taiwan’s Critical Digital Lifeline: An Analysis of Taiwan’s Undersea Cable Network Resilience” by the authors. The paper was presented in the Taiwan Internet Governance Forum (TWIGF) Tutorial Workshop on August 20, 2024.

One of the most frequently used words in Taiwan in recent years must be “resilience.” The government talks about it, and civil society actors are also setting up programs to prepare the public for it. Taiwan clearly needs resilience as the island withstands daily external interference and persistent threats of a complete blockade from China.

Resilience covers a lot of ground and can mean many things. For example, it might mean the ability to withstand adversity and the elasticity to recover from interruption. Yet today, when all areas of social and economic activities depend on ubiquitous digital communications, it is easy to forget the most basic and critical layer of the resilience of them all — the 15 undersea cable systems that keep the island of Taiwan connected with the rest of the world. These vital infrastructures provide over 100 Tbps of Internet bandwidth, supporting one of the highest Internet penetration in the world, or 21.71 million Taiwanese users. All of Taiwan’s critical industries, government and national security functions, and social activities depend on them.

And Taiwan actually has a long history of experiencing internet disruptions especially due to earthquakes that have damaged its undersea cables. Most recently, in February 2024, two undersea cables connecting Matsu, Taiwan’s outlying island only 9 kilometers from the Chinese mainland, with Taiwan’s main island were allegedly cut by a Chinese fishing vessel and a Chinese cable ship, respectively, within a week. The incident sent a warning signal across Taiwan.

Yet, Taiwan's biggest risk is not the disconnection of Matsu or other outlying islands but the possibility of the whole nation being cut off entirely. To strengthen Taiwan’s critical digital lifeline, the government must investigate the strategic viability and the potential incentives necessary to build its own domestic cable repair capabilities. It can leverage working with its well-established shipping and ship-building industry and explore cooperation with leading US or Japanese companies and fleets with undersea cable construction and repair expertise. For example, SubCom has commissioned a new deployment center in Subic Bay, Philippines, to serve as its regional logistical staging center. Why not Taiwan?

Risks and opportunities

Without a doubt, undersea cable disruptions have become a focus of international concern. From natural disasters such as the 2022 underwater volcano eruption near Tonga to the “accident” involving a Chinese cargo vessel that damaged a gas line and data cables in the Baltics in October 2023 or the Yemeni Houthi rebels’ attack on cables in the Red Sea in 2024, undersea cables have become a critical asset for economic and national security as well as a target in any conflict situation.

It is also important to note that one of the biggest problems with damage to these cables is the time it takes to repair them. A few highly specialized companies dominate the plumbers of the undersea cable business, including SubCom of the US, NEC of Japan, Alcatel of France, and the rapidly emerging China’s Huawei Marine Network. Moreover, for profit-driven reasons, these companies often place more emphasis on building new cables than repairing them.

There is also a common fallacy that satellite communications can replace cable connectivity, a notion that the hype surrounding Starlink’s support for Ukraine may have amplified. In reality, the west side of Ukraine remains connected to countries such as Poland, providing options for civilian connectivity. Satellite connectivity primarily supports critical government and military operations.

But the bad news for Taiwan is that it cannot depend on Starlink. In a 2022 interview, Elon Musk, owner of SpaceX, which provides the Starlink service, openly admitted that Beijing officials complained about his rollout of Starlink in Ukraine. They also told him not to launch Starlink in China, which, considering Chinese officials’ territorial claims over the island, very likely extends the prohibition to serving Taiwan.

That explains why Taiwan’s announced cyber resilience strategy from the Ministry of Digital Affairs (MODA) has focused on experimenting with the feasibility of low and medium-earth orbit satellite systems by working with other emerging satellite Internet providers from Europe that are significantly behind Starlink. And Taiwan’s Space Agency (TASA) also plans to launch six satellites from 2026, at a cost of US$1.23 billion. But, the Taiwan government admits that these efforts will “prioritize the deployment of equipment in outlying islands, remote villages, and areas without heterogeneous communication backup.” In other words, the satellite options are primarily just the backup for connecting within the island.

So, what about the most critical threat of all — being cut off altogether from the outside?

The need to think out of the box

Taiwan’s current situation, while challenging, also offers an opportunity to think creatively, explore new solutions, and create new opportunities as the geopolitics and geo-economical risks of Southeast and East Asia are being re-aligned.

Since 2019, the US government has cut off Hong Kong by no longer issuing licenses for any US operators to connect or terminate their cables to the special administrative region of China. As a result, Google, Meta, and Amazon have redirected their cables to Taiwan, the Philippines, and Guam. The South China Sea, already one of the most congested waterways in terms of undersea cables, is also becoming increasingly contentious and treacherous. Since 2023, China has started to impede new undersea cable projects by requiring permit applications for seafloor prospecting and any engineering work, even outside its internationally recognized waters.

These factors have transformed the traditional trans-Pacific cyber corridor, which runs from the western US coast to Japan, through Hong Kong, and finally to Singapore. Now, more and more new cable investments route through Guam and the Philippines, then around Indonesia and Malaysia, and back up to Singapore. This re-alignment affects not just Taiwan but other East Asian countries like Japan and South Korea. Japan is actively seeking new cable opportunities not only in North America but also across the Arctic and the Nordic countries of Europe.

That is why Taiwan must seize the opportunity and partner more closely with its two nearest northern and eastern neighbors, Japan and the Philippines, to make itself part of a “transfer station” of this new alignment of digital traffic, providing more redundancy for its connectivity while making the island a new Internet hub of East and Southeast Asia.

To make this work, Taiwan must rethink and devise its playbook to entice more investment for undersea cable infrastructure, which traditionally has been dominated by consortiums formed by telecom companies but is increasingly being challenged by more deep-pocket Big Tech players such as Google, Microsoft, Meta, and Amazon. Here, Taiwan may consider borrowing part of the European Commission’s recommendations on “Secure and Reliant Submarine Cable Infrastructure,” where the EU countries take a holistic approach that focuses its policies on not only the cables themselves but also the landing stations, repair centers, fleets and vessels, and so on. For projects deemed favorable to “European interests,” financing may be possible through coordinating with national investment banks in Europe or from respective member states, as well as private investors.

If Internet platform companies find it necessary and beneficial to invest in the infrastructure that they depend on rather than relying solely on telecom companies, why shouldn’t other critical industries do the same? For Taiwan, this could mean that the key players in its semiconductor and electronics supply chain, as well as companies in the financial sector, should also invest. To be more direct, if Huawei can invest in cable construction and compete with TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), at the same time, why can’t or shouldn’t TSMC, as not only Taiwan’s flagship chip company but also one of the most critical pieces in the world’s semiconductor supply chain, invest in maintaining global connectivity for itself and Taiwan?

To make all this happen, Taiwan should establish a multi-stakeholder expert group on digital resilience, incorporating inputs from industries, civil society, and academia and prioritizing new ideas. Even more important, Taiwan’s government must elevate its digital resilience strategy to its highest level of policy discussion and decision-making. In other words, the technical bureaucracy, such as MODA, will not be sufficient or efficient enough to coordinate between different agencies and ministries. To keep Taiwan on track, the highest levels of the executive branch, or the president himself, must take the lead.

Authors