Sexual Challenges Are Promoted on Facebook to Trick Girls and Teenagers in Colombia

Natalia Herrera Durán / Mar 7, 2025The article below is an English translation of an article originally published by the investigative journalism consortium Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (El CLIP). It is part of the “Innocence at Risk (Inocencia en Juego)” project, a collaboration between Tech Policy Press, Professor Lara Putnam, and El CLIP, which includes a series of independent reports coordinated by El CLIP and published in El CLIP, Chequeado, Crónica Uno, El Espectador, and Factchequeado.

Ilustration: Alejandra Saavedra

Through challenges posted on public Facebook groups, about topics that might interest girls, boys, and adolescents between the ages of 9 and 14, potential sexual abusers are looking to manipulate them into sending sexually explicit content. Colombia is first in Latin America in terms of the number of minors that have been contacted online by people they don’t know, and that have been asked to send nude or semi-nude images online.

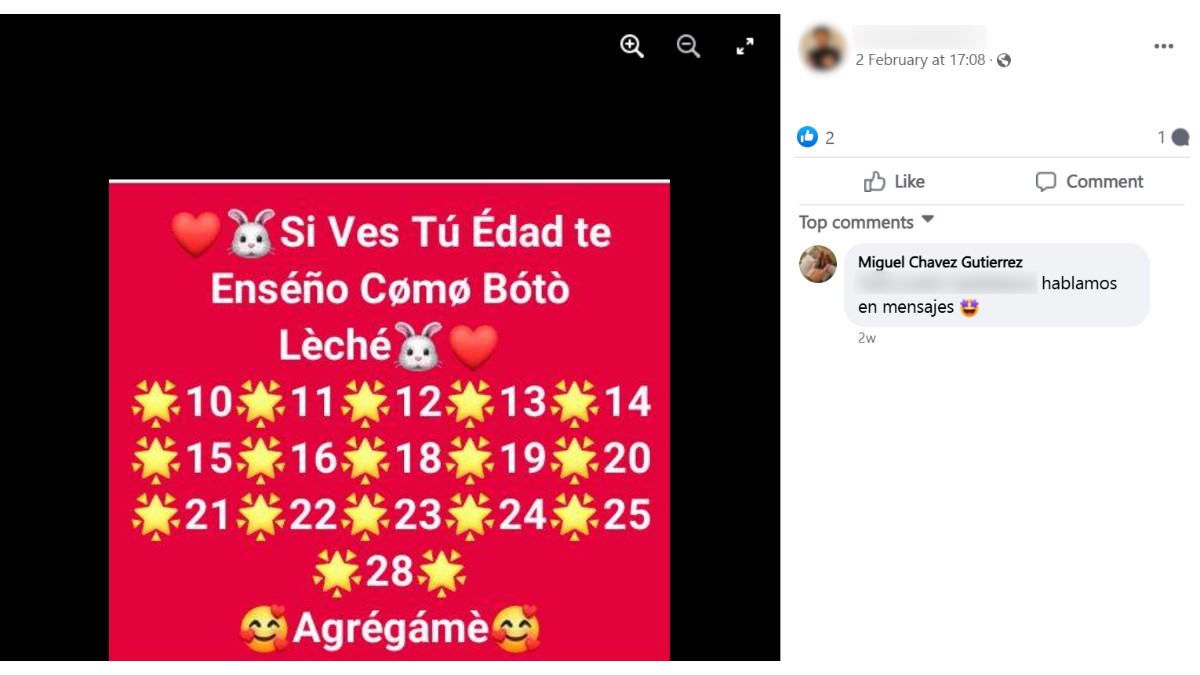

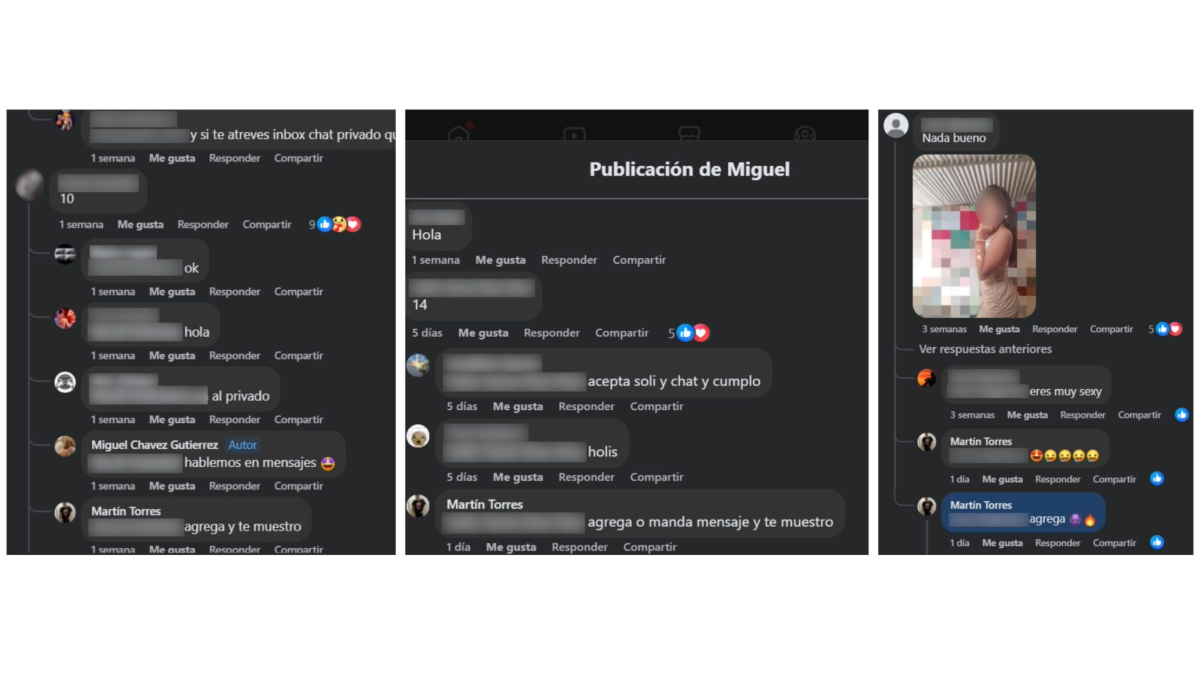

“If you see your age, I can show it to you on private message: 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and more (sic),” reads the text over an image with a blue background, adorned with red heart, love letter and fire emojis. “13” is the reply of a Colombian user who, in turn, gets replies from multiple users who invite her to chat privately. One of them says: “add me or send me a message and I’ll show it to you? (sic).” This is a user who goes by “Martín Torres” and whose profile picture is an image of an adult man, although we couldn’t fully confirm his identity, because he didn’t reply to the questions we sent him through Facebook.

Screenshot of one of the challenges shared in the public group “Fondos de pantalla para mejores amigas,” where minors are contacted for sexual purposes.

This “challenge” was posted in January by an anonymous user in a group for “best [female] friends,” whose content is mostly unrelated to its name. This is a public group that was created on July 7, 2021, and that had 182,944 members by December 2024. By February 2025, its members decreased by 701. Many profiles are created and deleted soon afterwards, but the pattern remains.

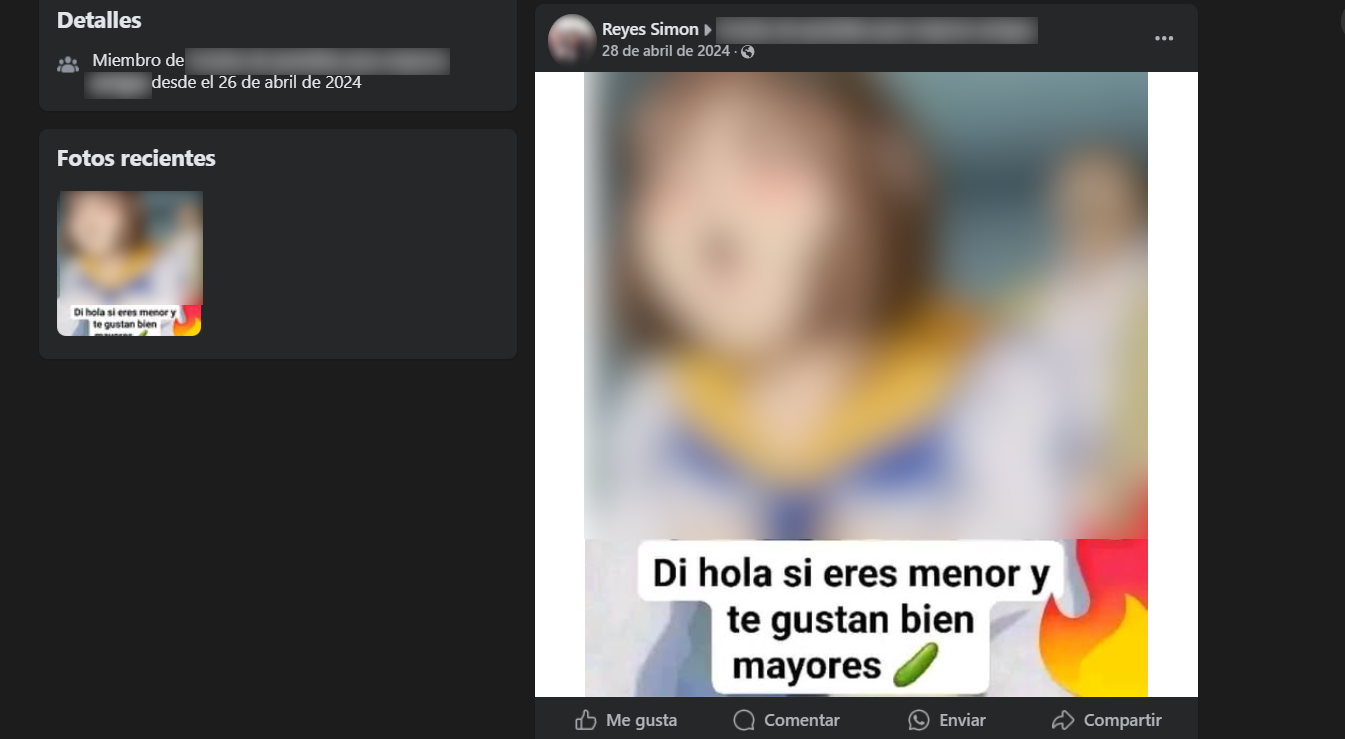

Another user who goes by the name “Miguel Chávez Gutiérrez,” whose Facebook profile info places him in Tlaquepaque, Guadalajara, Mexico, asks to “chat by messages” with a female user who is 12 years old from Tolima (in the center-west of Colombia), in a reply to a post that says “If you see your age, I’ll show you how I spout milk (sic)” Another user, going by the name “Reyes Simon,” whose profile says he lives in Cartagena, Colombia, shared a cartoon image of an older, mustachioed man, who seems to be having sex with a young girl in a school uniform, with an added fire emoji and an overlaid text reading: “Say hi if you are younger and you like much older men (sic).” We contacted both users, but did not get any response from them by the time of publication.

Screenshot made in February 2025, of an image posted by the user “Reyes Simon” in a public Facebook group.

In this and other Facebook groups, adult men use “games” or “challenges” to find minors to get them to share explicit sexual content or to participate in conversations including such content. Many of the users at risk are between the ages of 9 and 14 and are from Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Cuba, and Honduras, among other Latin American countries.

This phenomenon repeats itself hundreds of times, as “Innocence at Risk,” a journalistic investigation in which El Espectador participated along with other four Latin American and US outlets, coordinated by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism, found.

Screenshot of one the more popular challenges in public Facebook groups to induce minors to share or participate in sexually explicit content.

“That is grooming,” say those familiar with the term. This is a word used to describe a crime that is increasingly common online: the sexual abuse and exploitation of girls, boys, and teenagers through digital means, done by adults who try to contact them for sexual purposes. Colombia leads Latin American countries in the number of minors who have talked online with people they don’t know, and also in the number of minors who have been asked by someone they don’t know to send them nude or semi-nude images, according to Grooming Latam, an organization created in 2014 to investigate and counter this phenomenon in Latin America.

The impacts of sexual crimes online

Stella Cárdenas is interviewed in her office. Cárdenas is the Director of Fundación Renacer, a non-profit that has been working over the past 36 years for the eradication of commercial sexual exploitation of boys, girls, and teenagers, through accompanying and assisting victims in Colombia.

During the conversation, Cárdenas reports with concern that in the last five years, cases of victims of sexual crimes who are minors and who have been lured through social media, such as Facebook, have increased. Most of them are girls and teenagers, between the ages of 9 and 14.

When Cárdenas is asked about the impacts these girls and teenagers have suffered after being the victims of sexual crimes in online spaces, such as social media, she breathes deeply, gathering strength to face a difficult moment, and says:

“These are very deep impacts. Even their attention, concentration, and memory are highly impacted. They struggle with thinking about the future, and can very easily turn to self-harm. They feel they are good for nothing. They think they can only be validated by male adults who sexualize them. But, of course, that is not the case. That is why it is so important to get them early care that, with psychosocial support, can help them rebuild their life projects and give a new meaning to their lives. It is fundamental and possible.”

Cárdenas is also direct in saying that sexual crimes that happen online are often the beginning of other types of abuse. Because, according to the cases she has dealt with, men who contact girls to ask them for videos or sexually explicit photos, often also ask them to meet in person.

Cárdenas says, for example, that in 2024 her organization took the cases of many girls, between the ages of 9 and 12, in a low-income neighborhood in Cartagena, who were lured by an abuser through a gaming and chat group about Peppa Pig (the famous kid’s cartoon about a little pig and her family [that reaches Colombia] from Brazil) on Facebook. The criminal, after having asked them for sexually explicit content in direct messages, convinced them to meet in person and manipulated, extorted, tricked, and sexually exploited them, until he handed them over to a larger sex trafficking organization, comprised of Germans, which was broken up by the National Police after the local community reported it.

Cárdenas also links cases of forced disappearance to chats started on social media. “We took on the case of a 12-year-old girl. Thanks to her family members quickly reporting her disappearance in a mall in Odelia (in center-west Bogotá), her chats on Facebook with a man she didn’t know, who told her to meet him at the mall, were found. Her cellphone was tracked, and she was found, drugged, in a car that was apparently abandoned.”

For Cárdenas, it is crucial to call attention to contacts between minors and strangers online because behind those chats, there could even be organized crime networks, and not just sexual offenders with personal aims. Colonel Juan Pablo Cubides, Director of Protection at the National Police in Colombia (DIPRO), understands this well: “Behind a ‘hello, what’s your name? Send me a DM,’ there is usually a criminal network that is hoping this exchange will be successful,” Cubides explains in an interview with this journalistic collaboration.

Cubides is in charge of a National Police unit that covers three separate areas: the Police for Children and Adolescents, Protection of People and Facilities, and Tourism. No one else in the Police Department is authorized to issue statements about sexual crimes against minors in Colombia.

The pursuit of an online crime

“There are organized crime groups that are connected with these pedophiles and, of course, there are national and foreign individuals we have identified, not only with the methodological programs from the Attorney General Office but also with Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) in the United States, our great ally in the investigation of these crimes,” Cubides added.

Cubides did not want to offer details of these criminal organizations because they are currently under investigation, but he did mention that the cities where most of these crimes are concentrated are Medellin, Cali, Cartagena, and Bogota.

Colombia’s National Police is the only police force in South America that is part of the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC), a non-profit, non-governmental organization that fights against sexual exploitation, abuse, and risk of disappearance with headquarters in the United States. It also has a Cybernetics Center to follow up on cases such as these ones where they have discovered that many of the sexual aggressors are family members or close friends of the minors’ families.

“There is a complex increase and a high frequency of boys, girls, and adolescents being affected in digital settings, to the point where this crime has increased almost every other crime,” Cubides claims.

This is why he emphasizes the urgency that we, as a society, must prevent these abuses: “We must continue speaking to girls, boys, and adolescents about grooming because the criminals use strategies to make themselves seem like one of their peers. Then, once they have gained their trust, they take advantage of the scenario to threaten them and claim they will leak the photos or videos they have sent unless they continue sending more explicit sexual content or meet to have close sexual encounters.”

Girls, the most affected

Cases of violence and sexual crimes against minors in digital settings in Colombia are underreported. The data that reach institutions are not detailed; they do not include the circumstances nor the social media sites where they were committed.

But, given the rise in cases, none of the government entities can turn a blind eye on the issue. To this point, the Colombian Institute for Family Well-Being (ICBF) gave the following information to El Espectador after information was formally requested.

The entity in charge of the protection of children reported that although there are no formal statistics in their database (SIM), it is aware of 706 cases of girls, boys, and adolescents that have started a judicial and administrative process in the entity regarding sexual violence and sexual exploitation in digital contexts, in the last four years as of September 2024.

The year with the most reports was 2021, with 195 cases, followed by 2020, with 162 cases, “possibly due to the confinement situation and a higher access and use of social media during the pandemic.”

Within this domain, it is notable that most of the victims of sexual exploitation in digital contexts are girls and female adolescents, with 85% of cases (601), in contrast with 15% of cases (105) where boys and male adolescents were the victims.

Girls continue to be the most frequently abused, and this, to Stella Cárdenas, speaks to our culture. “We have a very violent society towards girls and adolescents, which revolves around a narco culture that sexualizes children. In Medellín, just to give an example, not long ago, I met with 12-year-old girls who told me that their plan was to finish ninth grade and turn to webcam jobs. Or girls in Bogotá who told me they started “to provide” when they were 11 years old and although their families sensed something was wrong, they didn’t ask too many questions, because they brought home dollars and, in any case, many of their mothers had been abused as girls,” Cárdenas says.

Screenshot of public conversations, available as of February 2025 in Facebook groups, in which, through dares, girls are asked to add adult males as “friends” so they can be shown or be asked for explicit sexual content through private messages.

Meta, the tech giant who does not do enough

Through a public request for information, El Espectador consulted the Attorney General's office to understand how investigations of sexual crimes online against children are being handled. As a response to this request, the Office replied that its database does not have a variable to identify the online contexts or social media networks where possible sexual exploitation against minors is happening.

They are, however, aware of how widespread this phenomenon is. In fact, they know the diverse methods the aggressors are using and they are concerned about them, like for example the video games that can be freely downloaded, oriented to girls, boys, and teens between 7 and 13 years old, where in order to obtain “more coins” users must send pictures of their private parts.

This publication was able to establish, through a request to expand on this issue, that the Attorney General's Office recognizes that Colombia needs international agreements for tech platforms to actively collaborate with the courts, with fewer obstacles. “For example, Meta does not easily accept requests for information for judicial purposes from the Attorney General's office, which specializes in investigating online sexual crimes against minors. Generally, investigators must repeatedly insist, and in serious cases, time is of the essence. It is important for these platforms to raise their own awareness of these crimes.”

When asked by this journalistic collaboration about how they collaborate with Colombian authorities in the fight against child grooming and exploitation, Meta replied through a spokesperson that they are “aggressively working” to combat child exploitation inside and outside their platforms. On the other hand, the Meta spokesperson said, “while predators constantly change their tactics to evade detection, our global teams and tools work to identify and quickly remove violating content.”

Meta also said that they "support law enforcement in its efforts to arrest and prosecute the criminals behind it,” and pointed out that, to that end, they have developed a portal called Law Enforcement Request Online Systems, “which allows authorities in Colombia, including police, public prosecutors and criminal courts, to submit take down, preservation and data requests in connection with official criminal investigations, indicating the specific content/account of interest.”

Meta also added that “Law Enforcement authorities can also use Meta's and WhatsApp's portal to submit emergency requests, where in cases in which production of user's data are needed to avert an imminent threat of physical harm (when the information is necessary to avert an imminent threat of death or serious physical harm to any person.)”. According to Meta’s spokesperson, the company’s transparency report states that, between July and December 2023, they “shared data in over 80% of government requests from Colombia.”

An unstoppable reality?

“We can and must urgently expand our response against sexual crimes in digital contexts, as well as our capacity to address them.” This is what Viviana Quintero believes. She is an expert psychologist in the online protection of minors who has been researching the issue for years, along with an academic team from the University of Los Andes.

A report from Fairplay for Kids, an American nonprofit organization that defends children’s rights above corporate interests, analyzed WhatsApp, Instagram, and TikTok. In this report from July 2022, they confirmed significant variations between countries in these seemingly identical platforms and concluded that some minors have less privacy and security than others, depending on where in the world they reside. According to the report, generally, European children enjoy higher levels of privacy and protection in these social media networks than other kids, for instance, children from Brazil, Colombia, Ghana, and Ethiopia.

“The higher level of protection for the children in the Global North than in the Global South is evident […] Everything exists only in theory like the supposed minimum age restrictions to create an account on these social media networks. One does not have to dig much to find dozens of cases of grooming and exploitation, against which the industry doesn’t respond in an effective way,” the psychologist asserted. After being questioned about this possible disparity, Meta’s spokesperson added: “Our policies prohibit child exploitation, inappropriate interactions with children, and the sexualization of minors; these rules apply globally, in different languages including English and Spanish, and across each of our platforms.”

Quintero believes, in any case, that facing this reality must also include a regulatory aspect. “It is necessary that corporations be compelled to be more accountable for the violence boys, girls, and teens experience in digital spaces in Latin America,” she insists.

Grooming Latam agrees. “We must continue to work together on a uniform legal framework that can unify criteria with regard to these transactional crimes throughout the region,” they believe. Facing this problem, however, requires strategies on several levels. Quintero believes, for instance, that Colombia needs a commitment at the highest level of the Government, which to date does not exist, to coordinate social efforts to fight this issue.

Additionally, the authorities and teams that enforce justice must be trained to tackle these cases, protecting victims, avoiding revictimization, prosecuting the aggressors and dismantling the criminal networks behind them. At the same time, they must ensure taccess to services of support and protection for these girls, boys, and teenagers. “It is required that those who have been affected receive long-term psychosocial support so they can properly heal from these traumatic experiences, with therapeutic, physical and mental aid.”

And, naturally, the shake-up we must undergo needs to have a cultural aspect. “We have found that in Colombia there is a high degree of normalization of violence and sexual activity with children under 18 years of age. These phenomena in cyberspace are highly risky because there are two other situations there that together foster the conditions for sexual violence. These are disinhibition, which is when a person, no matter their age, feels alone in front of a screen and thus more prone to doing things they probably would not do in public, and deindividuation, which means that it is more difficult to see the reaction someone is having to a violent action through an online platform. This increases the ease with which this type of violence can happen online.”

So, what can we do? Quintero believes that ending the normalization of violence and questioning ideas that validate it are the first steps. For example, thinking that girls look for adults “because they like it” or “because they want something in return.” Public policy and educational programs are also needed so children and teenagers learn to recognize the risks of these environments, but also so that their families can act and prevent or neutralize their impacts.

Our digital world is not yet designed to guarantee children safety. This is what the authorities we consulted believe and they agree that the call is to continue working in multiple spaces (in the government, the courts, the classroom, tech corporations, academia, media, family) on the prevention of online sexual exploitation against minors. This, along with more robust and articulated legislation in the region, and the promotion of a cultural change that allows longer and less sexualized childhoods in Latin America, will help to decrease the risks of the web for each and every girl, boy, and teenager.

Innocence at Risk is a journalistic investigation that reveals the risks of online sexual abuse faced by minors in Latin America on Facebook and other social networks. Led by the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), in alliance with Chequeado (Argentina), Crónica Uno (Venezuela), El Espectador (Colombia), Factchequeado and Tech Policy Press (United States).

Authors