Risks of State-Led AI Governance in a Federal Policy Vacuum

Katherine Grillaert, Matt Kennedy, Chinasa T. Okolo / Feb 6, 2025

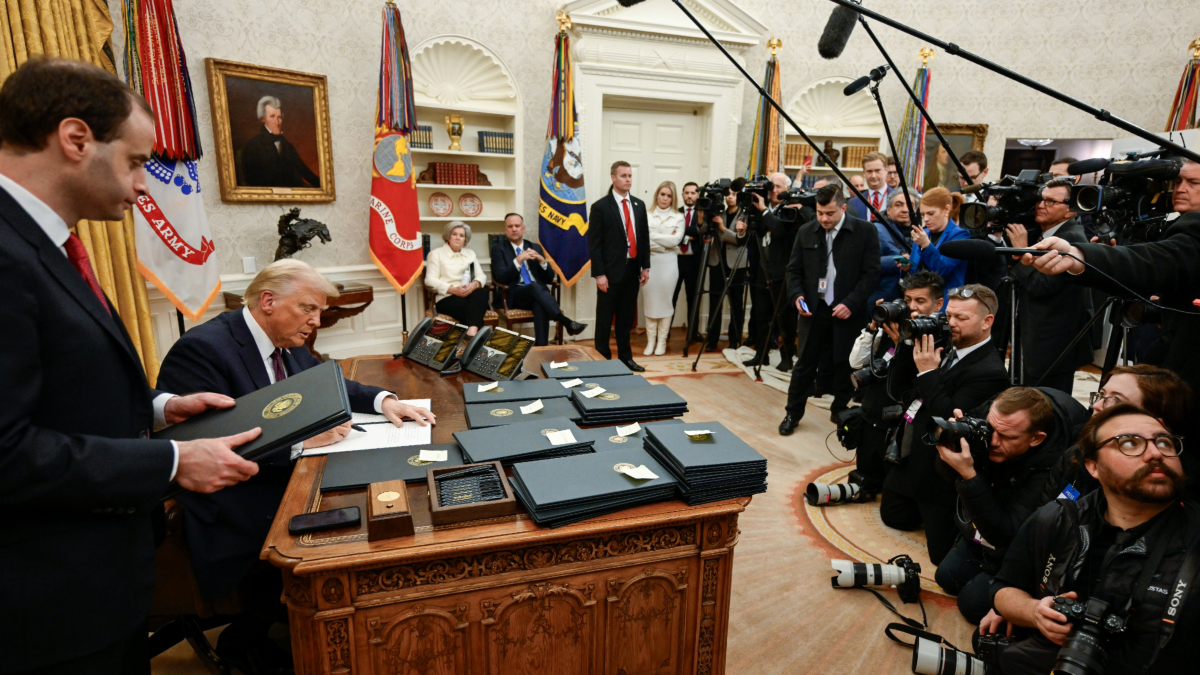

Washington, DC - January 20, 2025. US President Donald Trump signs a pile of executive orders. White House

While the EU and the UK move forward with comprehensive legislation on data privacy and artificial intelligence safety and equity, the Biden administration exited with only vulnerable accomplishments, such as an executive order on AI that leveraged the existing power of federal agencies, a memorandum of understanding on AI safety with the UK, and a joint roadmap for trustworthy AI with the EU.

Upon taking office, President Donald Trump moved quickly to repeal Biden’s executive order and issue his own order, "Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence," signaling an aggressive deregulatory pivot. This order calls for an immediate review and potential reversal of any actions stemming from the Biden order that are not aligned with the Republican policy of global AI dominance. Meanwhile, newly-appointed AI czar David Sacks, a prominent Silicon Valley investor with ties to Palantir and xAI, will further champion minimal regulation in his role advising and coordinating Republican policy.

This deregulatory stance extends beyond the executive branch, as evidenced by Senator Ted Cruz’s (R-TX) recent letter to the Department of Justice. His claim that the UK’s AI Safety Institute is a suspect “foreign agent” that may seek to influence US AI policy lacks substance. Still, it signals an American retreat from AI regulation in favor of technological supremacy.

What do these signs portend for federal AI policy? To what extent does this elevate the significance of US state AI policy? And what are the risks of allowing – or forcing – states to play a greater role in creating such policy? We outline three risks: first, using California as our example, there is the likelihood that, despite notable prior successes, states will prove less well-equipped to resist AI industry pressures; second, in the absence of a clear federal policy direction, states may struggle to implement “patchwork” AI governance; and third, foregrounding states undermines US AI leadership abroad, and degrades American AI security and diplomacy.

Power Not Quite to the States

Despite President Trump’s pledge that his presidency would transfer “power from Washington, D.C., and [give] it back to…the American people,” his first administration actively interfered with states’ rights to self-govern. California, in particular, took an assertive stance against federal overreach. After the FCC repealed net neutrality, California restored protections with its own bill, SB 822, prompting the Trump administration to sue the state in an unsuccessful effort to block the law. Over his first term, California spent at least $41 million defending its policies in court, underscoring the high stakes of state-federal conflicts during this period.

Nationally, with more than 60 state-level AI bills enacted in the past two years, states have a clear interest in frameworks that protect their constituents’ safety and privacy. More than ten states have considered legislation that addresses algorithmic harm and discrimination. However, these types of laws are likely to be a target of federal interference with states' rights, as Congress is already debating restrictions on federal agencies to prevent equitable AI design that considers disparate impacts on protected groups.

Even in a landscape of deregulation and federal interference, California has demonstrated that states can turn to the market in service of the will of the people. In a major win, when the first Trump administration weakened vehicle emissions standards and revoked California’s waiver to allow stricter requirements, the state collaborated with major automakers to uphold a voluntary emissions standard for cars sold nationwide. But while California has made efforts to collaborate with nonprofit advocates for algorithmic fairness, it is also susceptible to home-grown industry pressure.

Public trust in AI is sinking due to concerns over bias, data privacy, and accountability; meanwhile, government agents with large interests in Big Tech grapple for market share. California Governor Gavin Newsom’s veto of the recent AI safety bill warns that states should be wary of politicians facilitating industry capture. And although California is earmarking $50 million for legal fights in preparation for Trump’s second term, the hypothetical list of conflicts notably omits AI regulation and data privacy. California's struggle to reconcile competing commercial, political, and public interests highlights the complexities of state-driven regulation.

Who’s in Charge? Patchwork Privacy and Power

In light of the first Trump administration’s targeting of California’s approach to tech regulation, an area in which conflict is likely to erupt between states and the incoming second Trump administration is data privacy and protection–a place where federal regulation is stalled. The increasing development and rapid adoption of generative AI technologies have introduced new nuances to the production, refinement, and use of data. Over the past few years, datafication has increased as companies search for new ways to leverage consumer data to train personalized machine learning models for AI tools, with a range of companies, including LinkedIn, Twitter/X, Adobe, and Hubspot, sneakily introducing new terms that automatically opt-in consumers to have their data trained for internal AI purposes.

Given that the average US citizen is unaware of just how much data is being collected from them and how to limit the collection, sharing, use, and sale of their personal data, a lack of federal data privacy legislation leaves Americans vulnerable to domestic and international companies operating within and outside the country, foreign governments, and other nefarious actors. Comprehensive data privacy law will become even more crucial to ensuring that the rights of American citizens are safeguarded and that personal, business, and government data is protected. However, it is not certain that a state-led, “patchwork” approach can deliver the protections such a law would provide.

According to the International Association of Privacy Professionals, only 19 states have passed comprehensive data privacy regulations. Current federal legislation primarily focuses on the privacy of financial, genetic, and healthcare data and protecting minors online but neglects other forms of personal data. Developing a federal data privacy law could enable such regulation to preempt patchwork state privacy and domain-specific regulation, enabling more comprehensive rights and protections for all U.S. residents. While the American Data Privacy and Protection Act was introduced in July 2022, the bill was killed by members of the California Congressional delegation who were concerned that it would preempt their state’s more expansive statewide privacy legislation. Federal data privacy law was recently revived with the introduction of the American Privacy Rights Act in April 2024, but it also failed to advance. It’s unclear if there is any prospect of a federal privacy law in the next Congress or whether the Trump administration would support it.

This lack of federal data privacy legislation, even with individual state leadership, has created the conditions for data theft, weakening consumer protections and potentially jeopardizing the viability of AI systems in markets with more stringent privacy requirements. Additionally, the growing number of state privacy laws serves as a cautionary tale for the challenges and limitations of patchwork regulation. Companies operating across multiple states face a complex web of overlapping and inconsistent requirements, which can make it confusing and costly to implement policies that comply with each jurisdiction. Developers, in particular, may struggle to adapt systems to meet these disparate legal obligations, increasing the risk of non-compliance. Such nonadherence could potentially lead to fines, increasing operating expenses while resulting in suboptimal consumer protections.

The precedent set by fragmented state-level data privacy regulations could extend to AI regulation, further increasing operational inefficiencies and heightening effective accountability and oversight for harms caused to consumers. Furthermore, the Trump administration may find that vague, patchwork legislation creates an intolerable level of risk for companies pursuing innovation – precisely the opposite of its pro-business agenda.

Patchwork AI Policy Undermines International US AI Leadership

A third risk is introduced by state-led AI governance: it may substantially undermine US AI leadership abroad, intensifying the risks we already face from foreign adversaries. AI development and its impacts span jurisdictions; so, too, does AI governance. To achieve meaningful governance – both to clarify the legitimate avenues for innovation and to ensure AI technologies provide a public good – cooperation between governments of all levels is essential. A core component of effective cooperation is policy coordination, whether between US states, other major markets, or various international actors. State governments within the US benefit, to some degree, from the natural level of coordination that occurs from working in the same federal system and coordinating on common issues. Likewise, the global community benefits from international efforts to coordinate the regulation of various emerging technologies, including AI.

American public participation in these efforts is vital. The US, via its AI Safety Institute (AISI), housed within the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), has played the role of prime mover in developing the International Network of AI Safety Institutes. Likewise, through its engagement with key strategic partners such as the member states of the Global Partnership on AI or the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Japan, Australia, and India, in addition to the US), the federal government is able to exert meaningful international influence upon the development of AI “for good,” that is, AI technologies aligned to democratic values. These initiatives are only available to sovereign states.

It is unclear whether the US will maintain its involvement in these efforts under the Trump administration, and there are signs that Republicans, in general, are suspicious of international efforts on AI regulation. In his letter to US Attorney General Merrick Garland, Sen. Cruz urged an investigation into potential violations of laws intended to regulate undue foreign influence allegedly committed by UK and EU AI policy entities during their interactions with the US AI Safety Institute. Denying our international partners the amenity of accessing US state and federal AI policymaking fora, while at the same time asserting that our own access to theirs must be maintained, undermines American AI leadership at a critical time in the adoption of AI across the world. It creates conditions that may diminish economic opportunities produced by the substantial mutual technology interests shared between the US and Europe (both the EU and the UK).

Reducing the federal role in AI policy also introduces a significant domestic risk: entrenching the “California effect,” thereby ensuring that California, and not Washington D.C., becomes the de facto center of AI policy in the US. Because of the substantial market power California wields, many foreign states already maintain embassies near Silicon Valley. Concentrating AI policymaking in the hands of the state that also wields the most substantial market power produces a conflict that can only undermine US AI governance leadership abroad. This can only produce dynamics that will render the US government less able to represent American AI interests globally. It will certainly not further deter foreign adversaries, partners, or allies from attempting to influence US AI policy further.

Conclusion

Allowing states to reach different determinations about safety, governance, privacy, and compliance requirements of AI systems in a context in which the federal government is disengaged or actively hostile precludes any serious engagement in AI governance with our international partners and allies. Without federal support, US states are neither sufficiently equipped nor legally invested with the powers necessary to resolve conflicts caused by foreign adversaries’ use of AI to target Americans’ data. Yet, in the absence of a strong federal AI policy, US states may feel as if they have no other choice but to take up that role themselves.

To ensure that AI developed domestically is safe, trustworthy, and governable, the incoming administration should seek to build upon the foundations laid by its predecessor and by the first Trump administration, not abandon them. Furthermore, the administration should bolster American data privacy protections by passing a federal data privacy regulation at long last–legislation that enjoys overwhelming bipartisan support among Americans. Lastly, the administration should strengthen international AI governance partnerships in service of responsible innovation, innovation that both safeguards American prosperity and security and protects democratic values and human rights globally.

Authors