Managing to Fight Disinformation

Michael Khoo, Lauren Guite / Mar 6, 2023Michael Khoo is climate disinformation program director at Friends of the Earth and co-founder of UpShift Strategies. Lauren Guite is program director at Environmental Defense Fund and leads its climate disinformation work; she also serves on the steering committee of the Climate Action Against Disinformation coalition.

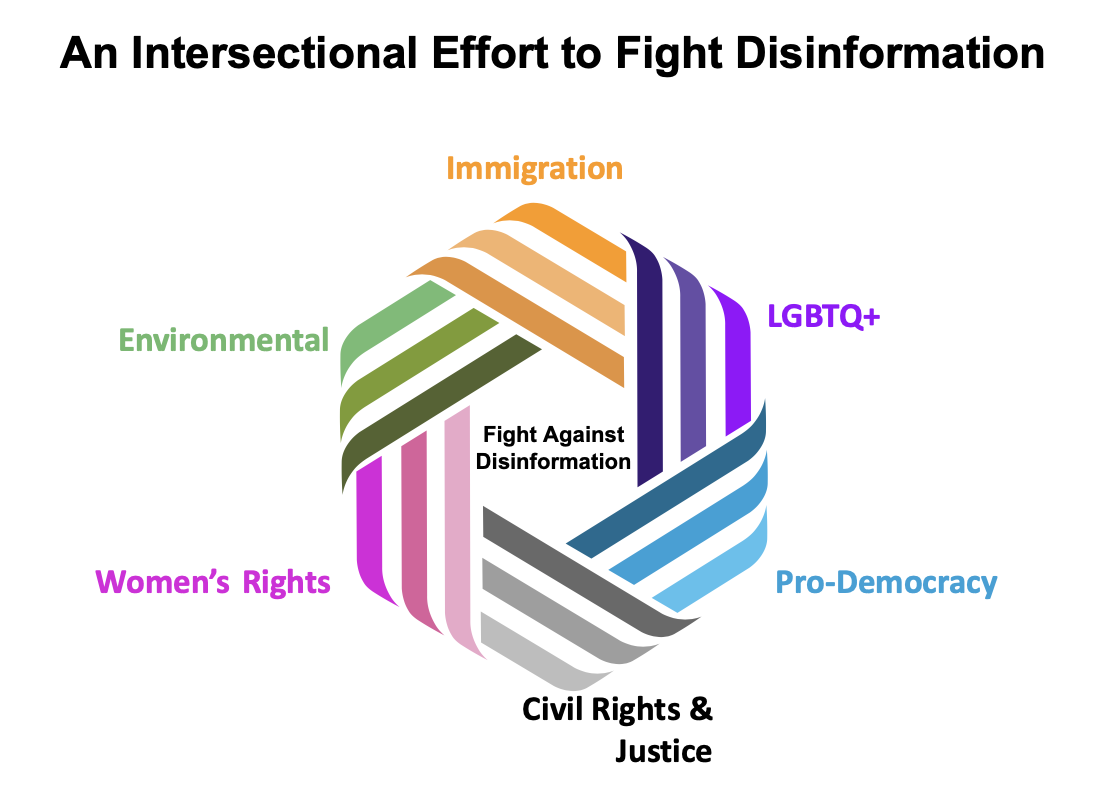

Disinformation is a threat to the stability of democracy and undermines our ability to tackle nearly every problem we face—from addressing climate change to securing LGBTQ+ rights to ensuring public health. Given the pervasiveness of the problem, what management practices are organizations using when working to combat disinformation? What organizational lessons can we learn from this new field?

In 2018, U.S. climate change organizations began researching disinformation, and we formed a small coalition to resource the effort. What we found was disturbing: small disinformation networks were, as Steve Bannon put it, “flooding the zone with sh*t” and delaying crucial climate action. But it became clear that this was more than a communications problem. It was also a new management problem: how to staff a response to something so sprawling?

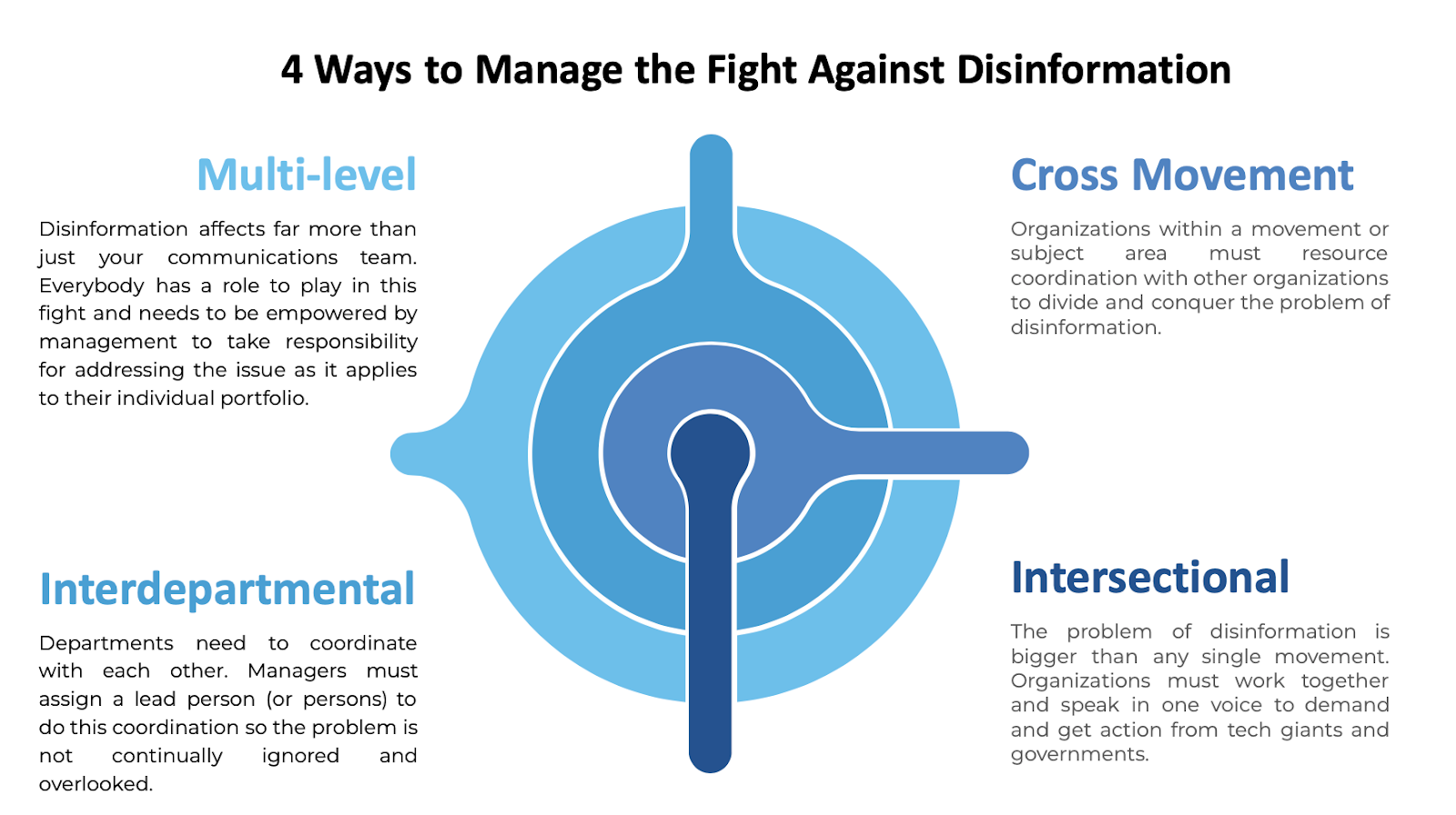

In our experience, managing to counter disinformation has required a new approach that is multilevel, interdepartmental, cross-organizational, and intersectional. But traditional management structures aren’t set up that way. To fight disinformation, we have to change how we operate in four discrete and interdependent ways.

Multilevel

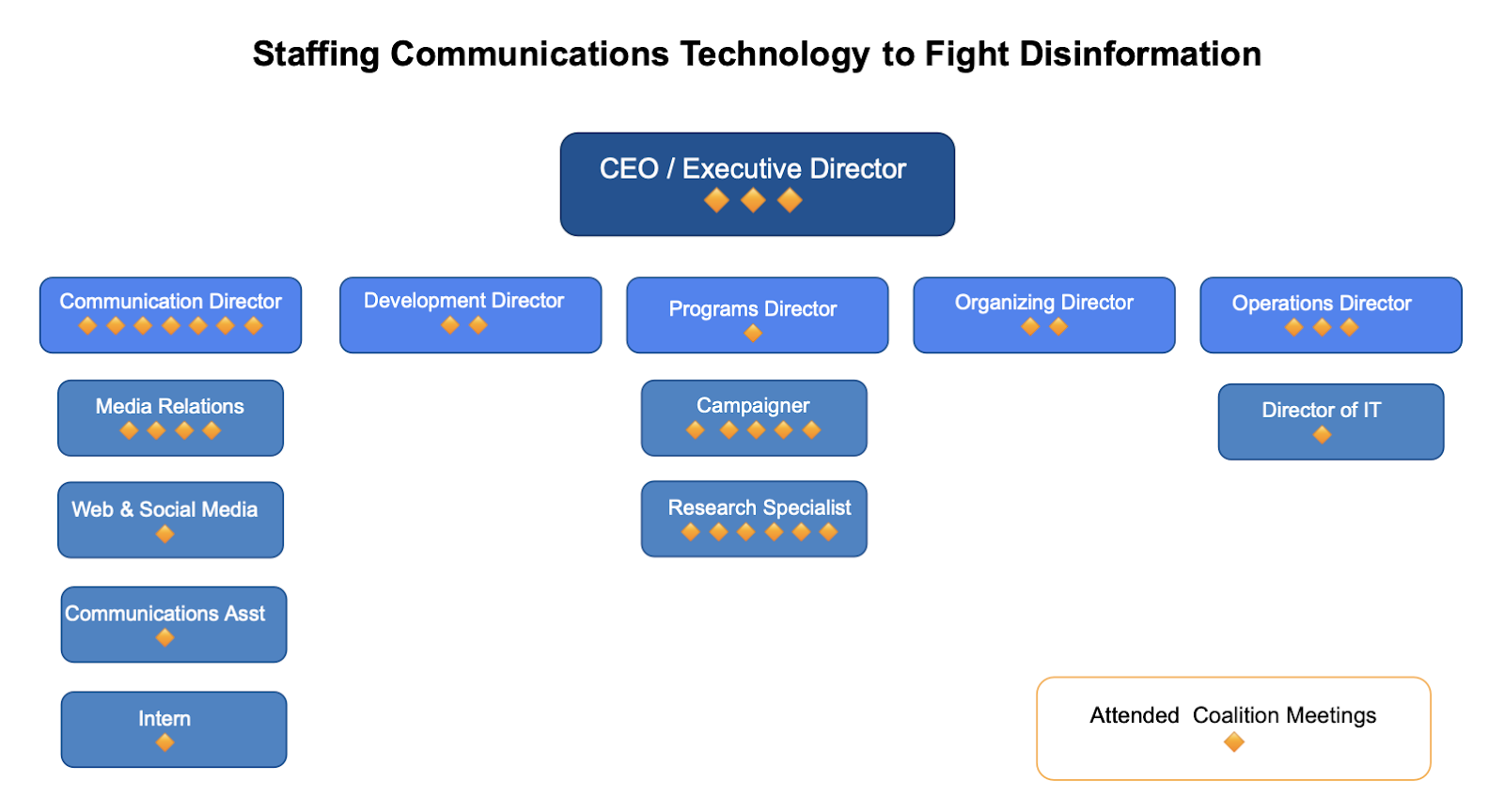

We saw that disinformation could be, and almost demands to be, managed at every level of an organization. When our coalition first came together, participating organizations sent everyone from the chief marketing officer of an $80 million group to the social media intern at a $5 million organization.

Social media staff, for example, care about the success of their content. Campaign directors care about winning their campaigns. Meanwhile, the CEO oversees the effectiveness of the whole organization. Disinformation was affecting all of their work, and we quickly saw that while everyone cared about solving the problem, no one was actually assigned ownership of it.

In fact, many people who attended these meetings have had to, on one level or another, downplay this work with their bosses. Or at least repeatedly justify why it is their responsibility and a necessary part of doing their job—be that winning policy victories or protecting the integrity of a social media feed. To visualize this problem, we created a generic organizational chart to place attendees and saw this sprawling result.

- What does this mean? If you are involved in advocacy on nearly any issue, disinformation affects far more than just your communications team. Everybody has a role to play in this fight and needs to be empowered by management to take responsibility for addressing the issue as it applies to their individual portfolio.

Interdepartmental

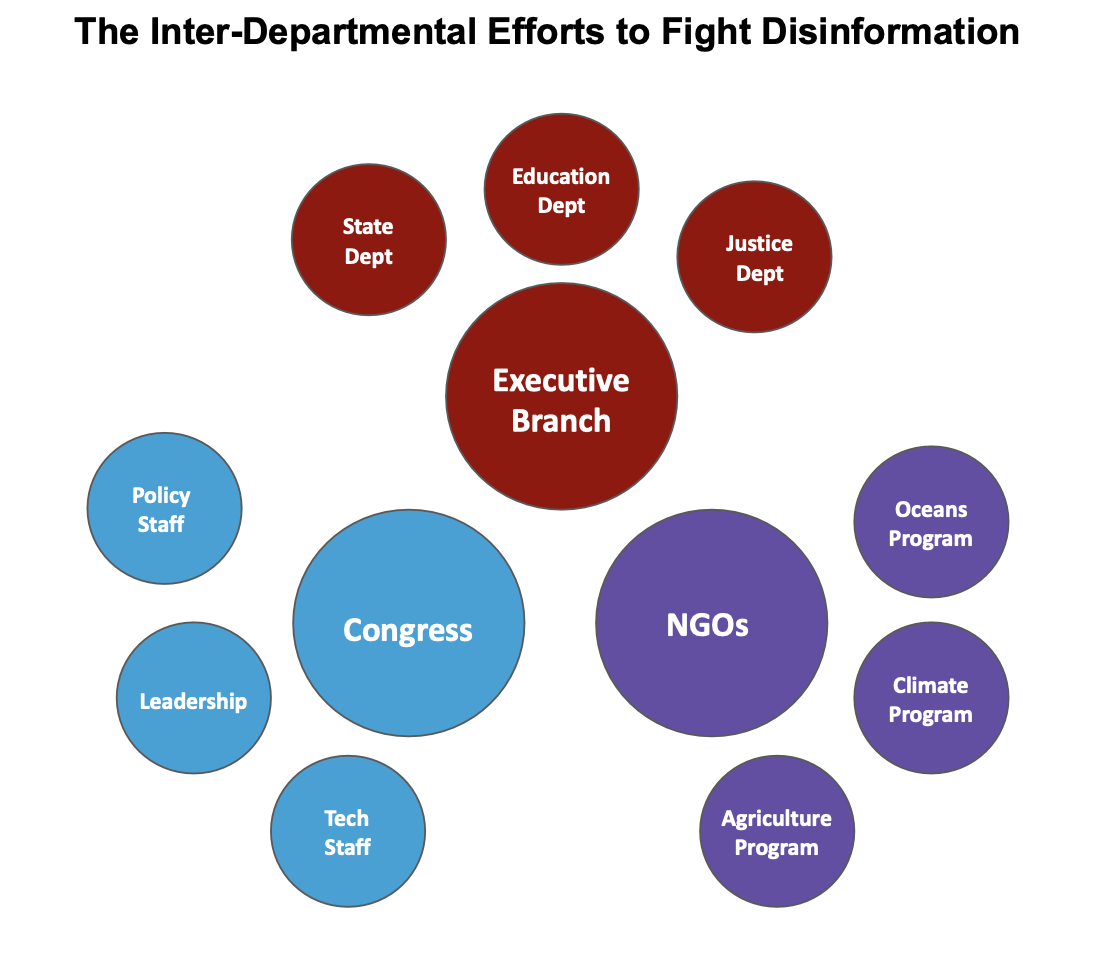

Next, we found that disinformation is an interdepartmental issue. Within an environmental organization like Friends of the Earth, disinformation affects the Climate program as much as the Food and Agriculture program. Those who want to disrupt the flow of information are not limiting their efforts to only a single issue—they are casting a wide net to create chaos and confusion, making this a problem that can impede every campaign.

Larger established entities have the same problem. When we work with Congress, staffers working on climate issues often tell us we should be talking with the tech policy experts. Or vice versa. When we approached the Biden administration, we saw that disinformation was a deep concern at many agencies, but each looked at it with a different lens, and with little coordination. The Department of Education said it was an education and media literacy issue, the State Department saw it as an issue of foreign actors, the Environmental Protection Agency saw it as an issue to take up with fossil fuel and tech companies. Even within agencies, there are similar levels of confusion.

In truth, disinformation cannot be addressed in a vacuum. No matter the scale of an organization, coordination is necessary across departments, and staffers need to be talking to each other and working together.

- What does this mean? Departments need to coordinate with each other. Managers must assign a lead person to do this coordination so the problem does not become a hot potato or fall through the cracks.

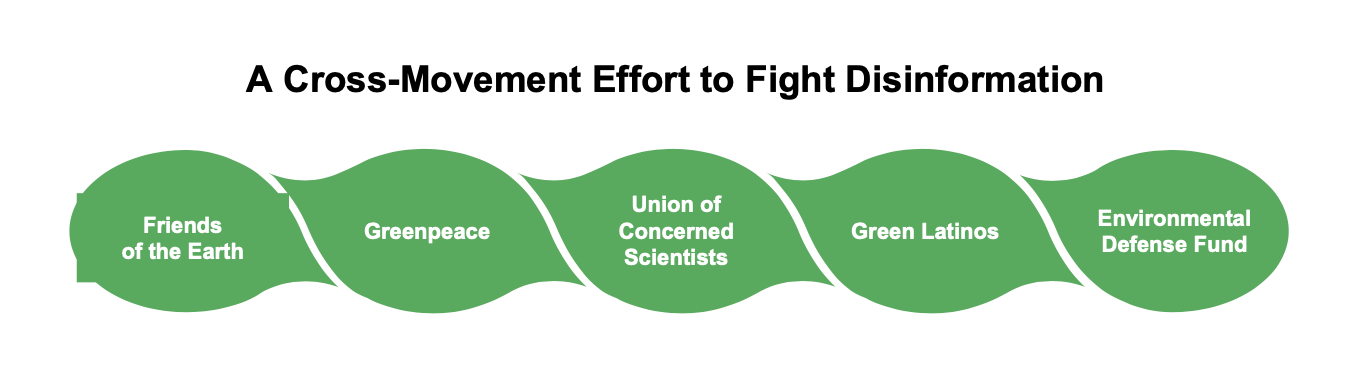

Cross-movement

Just as no single person or department within an organization can singularly stop the problem of disinformation, no single organization within a broader movement can effectively address the disinformation challenge. But movements as a whole must. A hard-left organization like Friends of the Earth cares about it as much as a centrist organization like Environmental Defense Fund. Despite differing perspectives on how to approach climate change, these groups face the same shared threat to their ability to communicate and campaign.

- What does this mean? Organizations within a movement or subject area must resource coordination with other organizations to unite over the problem of disinformation—and bury old hatchets.

Intersectional

Last and certainly not least, disinformation is a challenge affecting every organization that cares about making our country a more equitable, sustainable, and stable place. It cuts across climate change, public health, LGBTQ+ rights, criminal justice reform, gun control, election integrity, and more.

For example, LGBTQ+ groups protecting trans youth need to see the data to understand how far disinformation threats have spread on Twitter. Climate groups want to know why top climate deniers are getting a free pass on Facebook’s own community standards. There are lessons to be learned from each issue that must be passed on to other movements.

You can see the nascent and powerful impact that is possible when a cross-section of groups join forces to demand that tech giants take action and provide greater transparency.

Over the last year, four social media companies have made some promising, if sometimes small, moves. Twitter was the first, creating a moderated climate topic, a rare unsung move we hope survives under Elon Musk. Google announced it was demonetizing climate disinformation. Facebook announced a climate science center. And Pinterest developed a robust policy to stop climate disinformation (which was lauded by former President Obama) and consulted broadly with intersectional partners in the LGBTQ+ and reproductive health spaces while doing so. Our climate groups joined the intersectional fight against Elon Musk’s Twitter takeover, pressuring advertisers to maintain community standards. His autocratic tendencies and lack of accountability could make the social network a “hellscape” (his words, not ours) that further destabilizes democratic debate, including on climate issues.

Our policy goals for Big Tech are not only simple but commonsense: basic transparency and accountability, the request for a “help desk” in the language of the country, the need for an easy-to-navigate appeals process, open reports on product harms, and enforcement.

These are policies any brick-and-mortar business already uses: When an airplane goes down, airline companies are required to unlock the flight recorder, which says how it happened, and share that data across regulators and the whole industry. A baby seat fails? Same standards of recall notices and liability for harm. But tech companies have been allowed to skirt these basic responsibilities.

More than voluntary action, we need meaningful regulation of these tech giants. Congress is decades behind in its understanding of how social media companies operate and their real-world implications. The EU is developing a framework to rein in tech companies that is focused on transparency first, but it will be in danger of being watered down. If it can remain strong, it could be a useful model for countries around the world. This is why politicians and policymakers need to be educated on these issues as soon as possible—and persuaded to take further action.

- What does this mean? The problem of disinformation is bigger than any single movement. Organizations must work together and speak in one voice to demand and get action from tech giants and governments.

Conclusion

Few nonprofits or governments are properly equipped to fight disinformation. We need to face this problem now, before it is too late to undo the damage. Organizations need real support to shift their thinking and make the structural and management changes required to win this war.

Philanthropic funders must support long-term staffing and management priorities that allow organizations to work together internally and with external allies. This will require a sustained effort and an openness to outcomes that aren’t tidy. Disinformation is a massive, messy, multi-pronged challenge—and any work to fight it is going to look that way for a long while, too. But while solving climate change itself is going to be incredibly complex, solving the amplification of disinformation is, by contrast, a simpler challenge. Humans wrote the code, and humans can fix the code.

Our coalition designed one early model for how organizations need to work—at every level, across departments, organizations, and issues—and we hope it gets built upon. With commitment and a shift in mindset, we can build organizations’ capacities to come together to manage the long-term problem that disinformation has become. That, in turn, will allow us to make the progress we know is needed—and possible—on the grand challenges facing our societies.

Authors