Making Sense of AI Policy Using Computational Tools

Tuan Pham, Evani Radiya-Dixit, Marissa Gerchick, Brooke Madubuonwu, Suresh Venkatasubramanian / Jan 8, 2026

"Analog Lecture on Computing" (Hanna Barakat & Cambridge Diversity Fund / Better Images of AI)

In recent years, policymakers have rapidly increased their efforts to regulate artificial intelligence and automated decision systems through new legislation. These legislative approaches, however, are not advancing in isolation and often borrow and refine language from one another, creating interactions between proposals that otherwise appear to be moving in parallel.

To better understand this complex legislative landscape, the Center for Tech Responsibility at Brown University and the American Civil Liberties Union deployed carefully selected computational methods to analyze legislative trends across 1,804 state and federal bills related to AI and automated decision systems introduced between 2023 and April 2025.

The bills in this sample — which we selected based on the presence of various curated keywords related to AI — have varying degrees of substantive requirements and applicability; for example, roughly 30% relate to establishing task forces, and many bills focus only on uses of AI in particular sectors, such as health care.

The culmination of this effort, a new report released today, demonstrates not only how computational methods can be used to analyze trends across multiple bills, but also how to investigate a given bill in-depth. It also offers recommendations on how to improve computational policy analysis.

Throughout the report, we carefully chose the tool — computational or otherwise — to match the job at hand, rather than more haphazardly applying AI-based approaches without careful oversight, illustrating how organizations and researchers can thoughtfully harness computational tools for policy analysis.

Here is a summary of our findings:

Analyzing AI policy across bills

Our research showed how computational tools can help policy staff quickly track trends over time and across states, as well as visualize similarities across bills to trace the overall reach of potential model legislation.

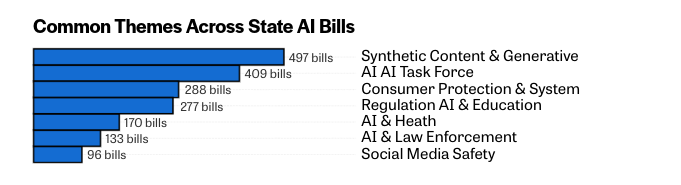

Using a technique called topic modeling, we identified common themes in AI-related legislation nationwide. We found almost 500 state bills focused on generative AI, with at least one bill from every state and more than 50 from New York alone, reflecting widespread state-level interest in regulating this technology. These bills often target deepfakes in elections or the dissemination of explicit synthetic imagery, sometimes through requirements like watermarking or disclosure of the origin of AI-generated content.

(Center for Tech Responsibility at Brown University and the American Civil Liberties Union)

We also observed a strong focus on establishing task forces to assess the impacts of AI, with over 400 state bills — many from Massachusetts and New York — and more than 100 congressional bills, demonstrating significant federal interest in creating AI-related task forces.

Computational analysis also illuminated how policy diffusion has taken shape in the AI policy sphere. Legislative bills often copy language from other bills or from model bills — template legislation drafted by advocacy, policy or industry organizations — with small but sometimes significant tweaks. For example, scholars have noted how the “California effect,” where laws in California ripple to other states, will likely play out in the context of privacy and AI.

To better understand such policy diffusion, we compared legislative texts to see how bills may share language with model bills. For instance, the Lawyers’ Committee Model Bill explicitly served as the foundation for the AI Civil Rights Act of 2024, but we found that it also shares substantial language with 11 other bills in Congress and states like Illinois, Massachusetts, New York and Washington.

We also examined another model bill that was reportedly developed and promoted by the large human resources company Workday, obtained by Recorded Future News. In addition to the six state bills identified by the publication, we identified another bill from Oklahoma that mirrors this model bill from the large sample of legislation.

Analyzing AI policy within a given bill

Our report also explores applying computational methods to explore a single bill.

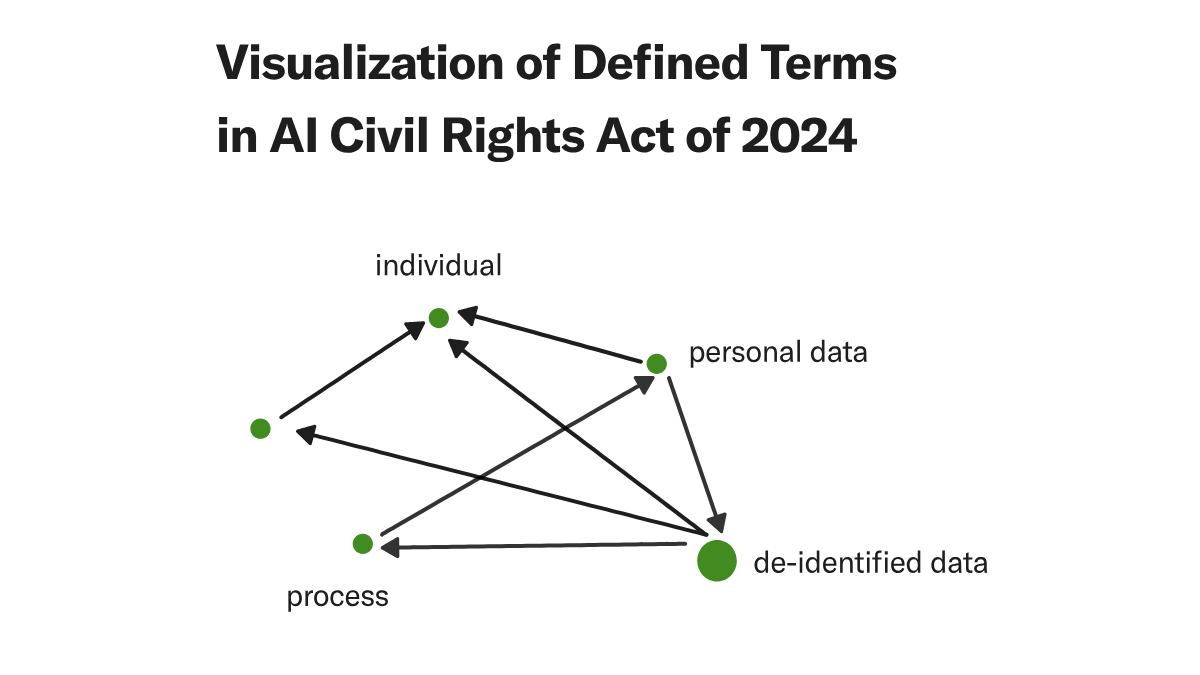

Bills often define key terms that are used throughout their texts and that significantly shape the bills’ scope and impact. In AI-related legislation, these definitions — of AI, AI's scope of use and the entities held accountable — have often been a subject of contention, as they establish the scope of the bill and boundaries for AI governance.

However, a single bill may include dozens of definitions that reference each other, and computational methods may make understanding those interlocking definitions easier.

We examined definitions from several bills, including the American Privacy Rights Act of 2024 and the AI Civil Rights Act of 2024. To better understand the relationships between definitions, we visualized them as a graph, as shown in the figure below with a sample of the definitions from the AI Civil Rights Act of 2024.

(Center for Tech Responsibility at Brown University and the American Civil Liberties Union)

Using methods from graph theory, we then investigated cyclical references in definitions — for instance, where term A references term B, term B references term C and so on — as such cycles can contribute to ambiguity and unintended loopholes in a bill’s application.

For example, the Fair Credit Reporting Act — a law that provides important protections related to credit reports — contains a cycle between two terms, “consumer report” and “consumer reporting agency.” These terms have been a source of significant debate in part due to ambiguities created by the cyclical reference.

This example illustrates how cycles can contribute to ambiguity and unintended loopholes where regulated behavior or entities are excluded from certain requirements. Identifying and potentially addressing such cycles in definitions can help policymakers improve a bill’s clarity and prevent loopholes before it becomes law.

Finally, we applied graph theory methods to identify key terms in a given bill. From the 60 defined terms in the American Privacy Rights Act, we found that the term “sensitive covered data” heavily relies on other terms and is likely central to the bill. As an umbrella that ties other terms together, “sensitive covered data” should have a clear and robust definition.

This type of analysis can help identify the terms most important to a bill, enabling policy staff to focus their attention and resources on strengthening these key definitions.

Recommendations

Our research unearthed two key recommendations to address the challenges that emerge when conducting computational AI policy analysis.

First, we urge researchers and policy staff to work together to create standardized formats and structures for legislative texts across jurisdictions. Establishing consistent file formats, structures of definitions and sections, annotation conventions and references would facilitate computational analysis of legislative data and make it easier for policy staff to track changes over time. The United States Legislative Markup data format and the Congressional Data Coalition group could serve as good starting points for cross-jurisdiction standardization efforts, for example.

Second, we encourage researchers and advocates to incorporate a multilingual perspective when analyzing AI legislation introduced in regions that, due to the history and ongoing reality of United States imperialism, are under US jurisdiction.

English-only analyses can overlook important policy developments, such bills in Puerto Rico that are written in Spanish and bills in Hawai’i that are sometimes written in Hawaiian. Computational methods, such as topic modeling, should be tailored to specific languages and incorporate social, cultural and legal context through engagement with native speakers and regional AI policy experts. Leveraging such context-specific language technologies would help provide insights into the diverse approaches to AI policy.

While our focus here is AI legislation, our research and recommendations can be applied to other policy areas seeing a surge in bills across jurisdictions, thus helping to understand and strengthen emerging legislation.

Authors