Lessons from National Digital ID Systems for Privacy, Security, and Trust in the AI Age

CJ Larkin, Renée DiResta / Jun 25, 2025Since their emergence in the early 2000s, national digital identity systems have promised substantial value for both governments and the public. At their best, they enable secure access to government services (such as healthcare, voting, social welfare programs, and/or taxation), reduce administrative friction, and can be used to verify identities for financial transactions or commercial interactions (including banking or employment verification).

In practice, however, not all national digital identity systems have delivered on that ideal. Some implementations have raised serious concerns about privacy, surveillance, exclusion, and data security. Others have faced backlash over centralized data collection, opaque governance, or mission creep into areas beyond their original scope. Adoption of these systems often hinges not just on utility or a legal mandate, but on whether people trust the entities controlling the system and handling their data. Transparency and a sense of user agency are central to that trust.

The recent rapid acceleration of generative AI and the imminent prospect of more ubiquitous agentic AI systems—artificial intelligence software capable of autonomously performing complex tasks, making decisions, and interacting convincingly—has renewed interest in digital identity writ large. Agentic AI is projected to become more prevalent in the immediate future, as human users proactively delegate tasks to credentialed agents. Generative AI can already produce voice, image, text, and video content increasingly indistinguishable from that produced by people, including, for example, voice replicas of specific individuals. While both generative and agentic AI offer many beneficial applications, there are also significant opportunities for increasingly undetectable abuse. In our research, one of us has focused extensively on adversarial abuse of agentic and generative AI, highlighting specific risks such as sophisticated impersonation attacks for fraud purposes, and manipulation of online discourse and interactions. As these tools become cheaper, more broadly accessible, and harder to detect, distinguishing real users from synthetic agents will become increasingly difficult.

One approach to this challenge is the development of privacy-protecting “personhood credentials” (PHCs). PHCs are envisioned as a means for users to voluntarily prove that they are real or unique non-AI individuals without revealing personal information. This is potentially a promising model for enhancing trust in digital interactions.

The success of any solution related to identity depends heavily on public trust, regulatory alignment, and integration into existing systems. This is particularly true if a government is involved, as state-managed identity programs often require a delicate balance between security, privacy, and public accountability. State involvement also amplifies concerns around surveillance, data sovereignty, and misuse. Yet with the rise of generative and agentic AI, it is increasingly likely that governments will seek stronger identity verification systems to counter AI-driven fraud and identity-based threats.

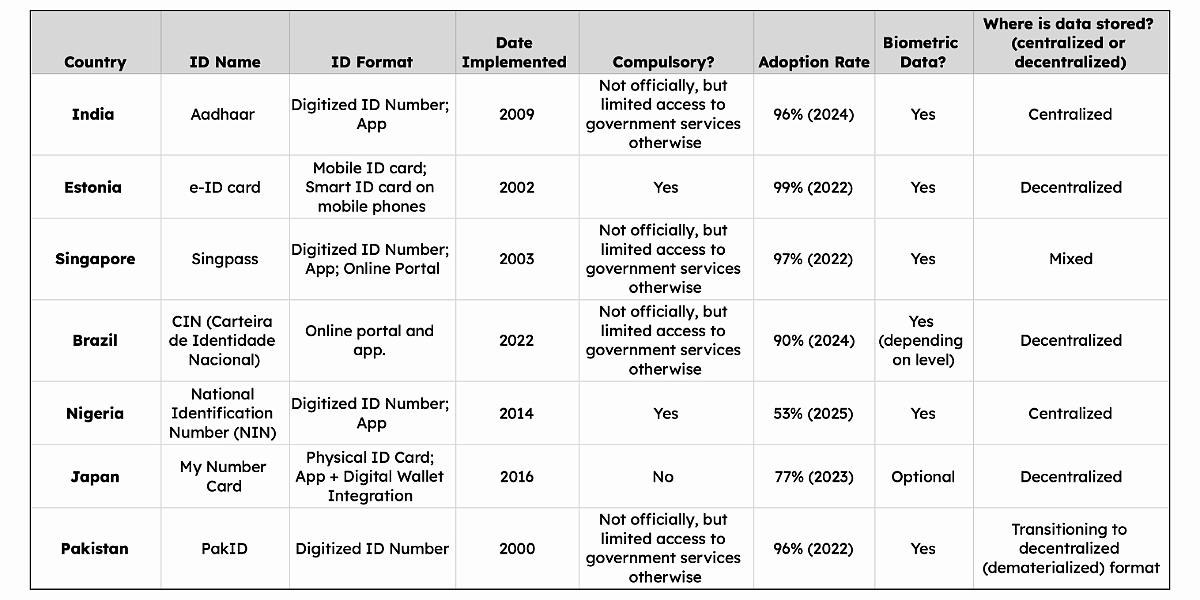

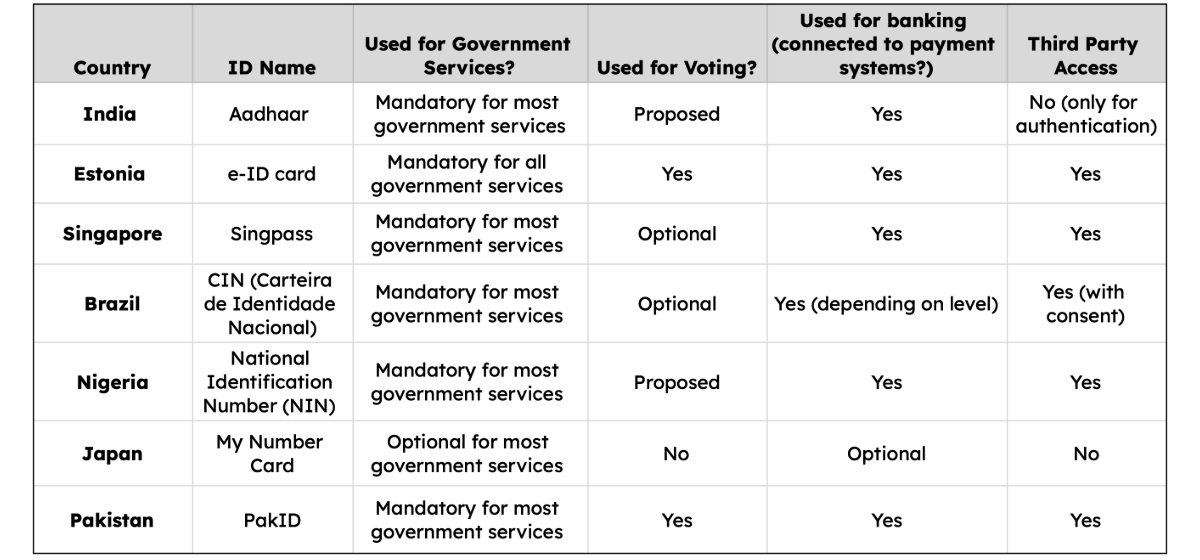

To understand how to potentially develop trustworthy, effective, and privacy-protecting identity systems in an increasingly AI-mediated and potentially authoritarian world, we examined how legitimacy and public value have been built—or undermined—in existing national digital ID systems. Adoption of such systems depends not only on technical infrastructure, but also on perceived utility, fairness, and accountability. Our analysis looks at seven countries—India, Estonia, Singapore, Brazil, Nigeria, Japan, and Pakistan—focusing on regulatory frameworks, adoption rates, public sentiment, market participation, and core system features. By assessing how these systems address privacy, security, and user trust, we aim to surface lessons relevant to the evolution of digital identity in the age of AI.

Survey of existing digital identity systems

In this section, we examine national digital identification systems across seven countries—India, Estonia, Singapore, Brazil, Nigeria, Japan, and Pakistan—offering snapshots that explore how different governments have designed, implemented, and governed their digital identity infrastructures. These snapshots reveal a wide range of approaches to regulation, enrollment, authentication, and data access. We focus in particular on system features, adoption dynamics, third-party integration, and documented privacy or security challenges.

Source data — India: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Estonia: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Singapore: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Brazil: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Nigeria: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Japan: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage. Pakistan: Date Implemented; Compulsory; Adoption Rate; Biometric; Data Storage.

India

India’s digital ID, Aadhaar, was established in 2009 by creating the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIAI). At the time of UIAI’s establishment, India lacked any form of centralized ID, and ⅓ of the country didn’t have birth certificates. As of July 2024, over 1.38 billion Aadhaar numbers have been generated (for over 96% of the country’s population). A 2019 survey found that 95% of adults use Aadhar at least once a month, with 90% of them being “somewhat or very satisfied with the program.” While India’s Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that Aadhaar cannot be mandatory, it is required to access many services nationwide. The ID is required to access government-to-citizen social services, and in most cases, is required for banking and healthcare. It has recently been proposed that Aadhaar identification should be required in order to vote within the country, sparking a debate about user privacy and anonymity in Indian elections.

Aadhaar requires biometrics. Historically, it has required iris scans and all ten fingerprints, but as of 2021, it has begun switching to face authentication. As of early 2025, over 1 billion financial transactions had been completed through Aadhaar using face authentication. In February 2025, the Indian government began allowing private companies access to Aadhaar’s face recognition technology. Two-factor authentication is required for Aadhaar usage, and the ID is not accessible to law enforcement. Aadhar has been susceptible to security breaches; for example, in October 2023, uniquely identifiable information such as the Aadhaar and Passport numbers of 81.5 crore (approximately 850 million) Indians was leaked onto the dark web. While there have been relatively few studies that critically analyze the security shortcomings of Aadhaar, the centralized nature of demographic and biometric data, alongside minimal additional security measures, is seen as the most significant cause for concern.

Estonia

Estonia’s digital ID (e ID card) was first introduced in 2002. The ID card is mandatory – 99% of Estonian residents have a digital ID (with the option of an “e-residency” version for non-citizens), and 70% report using their digital IDs “regularly.” The ID card serves as the primary legal photo ID and travel document in the country, and is required for nearly every government service (notably, 100% of Estonia’s government services are conducted online) and most private transactions. The ID card allows for the use of “digital signatures,” voting, tax identification and information, and e-prescriptions. Estonia’s government estimates that in the first twenty years of the program (2002-2022), over 800 million digital signatures were given through the ID card. Private and third-party entities are permitted access to ID card information, provided they comply with the country’s decentralized data exchange and obtain contractual consent from the end user.

While the ID card is issued at birth, it does require biometric information as well as either a passport or an EU ID card. It is viewed as relatively secure, due to its use of encryption and a decentralized database. The ID uses “x-road” open-source software, which provides “unified and secure data exchange between private and public sector organizations.” The ID card has been generally viewed as non-controversial within the country, which is in part credited to a general trust in the Estonian government and the longevity of the Digital ID program. There is also transparency around access, in the form of data access logs and a “Data tracker” tool that shows citizens who accessed their personal data, when, and for what purpose. While there have been minimal cases of privacy or security breaches, a 2020 case in which e-pharmacies accidentally allowed patients to access other patients' prescription information resulted in fines.

Singapore

Singapore’s digital ID, Singpass, was launched in 2003, in the form of a government-issued single ID and password system to access agencies. Since then, Singpass has shifted to primarily an app form. Singapore’s government reports that Singpass has a user base of “more than 4.2 million users. Singpass serves approximately 97% of Singapore Citizens and Permanent Residents aged 15 and above and facilitates about 300 million personal and corporate transactions every year.” Singpass allows access to “over 460 Government agencies and private sector organizations across more than 1,700 services.” Businesses are allowed access to Singpass’s API to “improve the customer acquisition and business process.” For example, corporate human resources departments are permitted to use Singpass’s face verification to assist in the hiring process, and third-party crowdfunding websites often use the Singpass API to confirm where raised funds are going.

Singpass requires biometric data, including facial scans and fingerprints, for registration and use. It is currently not entirely decentralized – Singapore’s director of National Digital Identity at the Government Technology (GovTech) agency, Kendrick Lee, refers to Singpass as a “federated ecosystem of somewhat centralized sources,” but mentions that the agency is exploring decentralized distribution models. Despite this federated system, Singpass has encountered numerous security and privacy issues. There are multiple cases of Singpasses being sold on the dark web (security researchers have reported a “significant rise” in SingPass accounts for sale in recent years), and there are sustained concerns about Singapore’s elderly population falling victim to phishing scams around their IDs. While facial ID authentication was introduced specifically to reduce this, there is minimal information around whether it has been effective.

Brazil

Brazil’s Digital ID, Carteira de Identidade Nacional (CIN) (part of the country’s ‘gov.br’ digitization efforts), was created by national law in 2017, and officially launched in July 2022. The stated goal of CIN was to serve as an improved version of the country’s paper ID system, while enabling a “secure and reliable identification of citizens to access digital public services.” Brazil’s CIN operates through a unique “three-level system” – bronze, silver, and gold – through which citizens can access different levels of government services through the ID in exchange for providing more personal information. Bronze, the lowest level, is offered to any citizen who creates an account and validates their information through a government agency (i.e., social security office, traffic department, etc.) – no biometric data is required, and access is allowed to “less sensitive digital services.” The silver level requires access to either facial biometric information or bank account information, and allows use of “all features of the gov.br digital services.” Gold, the highest level, requires the user to confirm their identity with facial identification based on “the Electoral Justice database, validate personal data through Gov.br by reading the National ID QR Code or through the official public key infrastructure.” This level allows for single sign-on access to government services, as well as “full access” to government services with “maximum security.” As of 2024, over “90% of adults and 96% of children under the age of five” had been registered for gov.br’s digital ID.

While the bronze level of CIN does not require biometric information, it is required to access most services provided by the digital ID. The ID is decentralized (using blockchain) and allows private third-party access, including law enforcement. In early 2025, Brazil launched a “Federal Biometric Service” to oversee and monitor the use of biometric information for gov.br. While an implementation plan for the service has not yet been released, it is intended to increase security around the ID’s use of biometric data. A report by conducted by the Data Privacy Brasil research association on CIN and gov.br isolated two primary “risks” that have come out of the country’s Digital ID system – first, the “abusive processing of personal data, due to the ICN’s information and governance architecture,” and second, the risk of excluding citizens “from accessing public policies, when using the CIN database to access the gov.br platform.”

Nigeria

Nigeria’s “National Identification Number” (NIN) was established through Nigeria’s National Assembly’s enactment of the “National Identity Management Commission Act (NIMC)” in 2007. The goal of NIMC was to create a “national system of identifying all citizens in order to accomplish the legitimate business of government – law enforcement, intelligence, social and economic development,” which resulted in the creation of the NIN. In 2010, the National Identity Database was established to maintain NIN, and as of March 2025, over 118.4 million digital IDs have been issued. Despite the success so far, it still is not clear if the country will be able to meet the issuance target—180 million enrollees by the end of 2026—that was set by the World Bank when it “restructured its funding arrangement for the digital ID project” in 2024. The NIN is mandatory and is required for nearly all government services (including applying for a Passport, registering for a SIM card, opening a bank account, and registering to vote.) Without access to a NIN, citizens would be unable to access bank account information, driver’s license, and risk cell phone deactivation. While NIN is issued at birth in paper form, its digital form needs to be “activated” (in person with supporting documentation) once the person has turned 16.

In January 2025, Nigeria announced that it will be launching a biometric-backed version of the NIN, called the “General Multipurpose Card (GMPC),” an “improved…three-in-one NIN-linked card with an embedded chip, which can operate online and offline.” The GMPC is anticipated to be issued through third-party banks and was designed to accomplish three primary objectives: facilitating access to government programs and services; acting as proof of identity; and enabling “economic and financial inclusion.” However, there are already concerns about the amount of biometric information held by NIN – it includes fingerprints, a facial picture, and a digital signature – and the centralized nature of the database (it is solely held by the NIMC.) Users have struggled with continuity in modifying their NIN information – for example, citizens have reported that personal information they changed with NIN (i.e., name, gender) is not accurately reflected within their bank account information. Elderly citizens have also reported being blocked by the NIN system, resulting in blocked access to their SIMs. Regaining access can be a struggle, as they must travel to centers that may be quite far from their homes, posing a particular challenge for those in poor health.

Japan

Japan’s “My Number ID Card” was launched in 2016 in an effort to digitize the country’s already-existing national ID system (which was established in 2002). My Number ID Card is a plastic photo-ID card with an IC chip containing the person’s photo, name, address, birthday, gender, and My Number. My Number ID is currently optional; it is used for most government services, but these services are still widely accessible without the use of My Number ID Card’s digital ID functionalities. As of December 2024, My Number ID Cards officially replaced health insurance cards in Japan. Third parties cannot access My Number ID Card’s information, although they are attempting to enter the digital ID space within the country.

The program has struggled with adoption rates and public skepticism. As of 2023, only 77% of Japan’s population had applied for the digital ID card. To increase adoption, Japan has been introducing more use cases for the card, in an attempt to make it both more appealing and more difficult to navigate government services without one. In March 2025, Japan announced it would begin integrating driver’s licences into the My Number ID Card. While this will technically be optional, using the Digital ID version of the driver’s licence will allow for benefits such as easier address changes and reduced licence renewal fees. Additionally, Japan announced that it will soon begin integrating the Digital IDs into Apple Wallets (projected to begin in late spring of 2025.) However, My Number ID Card has continued to struggle with public trust – a July 2023 poll found “that 58% of respondents were against using ID cards for healthcare purposes, while 80% said they did not believe that the government could fix the problems caused by the government in terms of connecting health files to digital IDs.” There have been over 7400 reported cases of My Numbers being linked to wrong health information, in the effort to integrate health insurance information into the Digital IDs.

Pakistan

Pakistan’s “PakID” is an online ID. Originally a paper ID, PakID was computerized in 2000, and as of March 2025, it was launched as a digital identity card. While PakID is not technically compulsory, it is required for all government services, such as social benefits, healthcare, public schools, and marriage records, as well as for bank account creation. PakID adoption rates are generally high – around 96% of the population, or 212 million people – and have been incentivized by rolling out social service programs tied to the ID. For example, after Pakistan launched the “Benzair Income Support Programme (BISP),” a poverty alleviation program, issuance of the ID to adults increased by 72% within four years.

The ID requires biometric data for user verification, and is third-party accessible (for services including banks and mobile cell service providers). PakID’s centralization under NADRA has caused privacy and security concerns (though they are currently in the process of decentralizing through their new dematerialized ID). Some of this concern stems from the format of the ID cards revealing all personal information; a citizen’s name, date of birth, address, family tree, and legal sex are all incorporated within the ID number itself. Notably, the sex identification aspect of the number has drawn concern, due to it revealing the person’s sex assigned at birth, regardless of whether they have changed their sex legally. Additionally, since the ID is tied to paternal lineage, there are concerns around the ID revealing sensitive information, such as marital status, without consent.

Sources — India: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Estonia: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Singapore: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Brazil: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Nigeria: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Japan: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access; Pakistan: Government Services; Voting; Banking; Third Party Access.

Critical dimensions of ID systems

The countries we examined are a subset of those that have instituted digital ID systems. Yet despite vastly different political systems, economic contexts, and regulatory frameworks among the countries considered, several themes emerge:

- Adoption is often driven by practical necessity: uptake is closely tied to whether ID is required to access essential services such as banking, benefits, or healthcare. We observed fairly high adoption rates regardless of whether the ID was legally mandatory or not, likely due to the need to have the digital ID in order to access government services and, often, private sector services such as banking and SIM cards.

- Privacy concerns are common, even in high-trust societies: Regardless of country, there were concerns or shortcomings around privacy. Some countries, such as Estonia, have taken steps to mitigate those concerns. Estonia’s online platform that allows for citizens to view if, and in what way, the government has accessed the information linked to their digital is unique in its degree of transparency.

- Safeguards are uneven: many systems require biometrics such as facial recognition or fingerprints, particularly for higher-security tiers. However, biometric data governance ranges from highly regulated (Brazil’s pending biometric oversight body) to more opaque or centralized models that raise concerns about misuse or surveillance. There were several countries that experienced issues with individuals being “scammed” (especially elderly populations) or phished out of their ID information, as well as issues caused by governments being unable to successfully link or secure individual level data.

- Vulnerable populations face unique risks: elderly individuals in Singapore and Nigeria have reported being locked out of services due to biometric mismatches. The structure of ID numbers has revealed sensitive information like assigned sex or marital status without consent.

- Decentralization is often more of a promise than a reality: Although Brazil touts blockchain integration, the EU promises third party providers, and Estonia uses federated data models, most systems we examined still rely on centralized issuers and data storage controlled by the state.

These facets reinforce that technical infrastructure is but one component of digital ID; the political and social dimensions are just as critical.

As digital ID systems evolve alongside advances in generative and agentic AI, several areas merit further research. These systems are not adopted—or trusted—just because they are functional. They gain legitimacy when people see them as useful, secure, and accountable. Just as our investigation suggests that public trust and perceived legitimacy are critical to national digital ID adoption, these same factors will shape the viability of decentralized and privacy-focused systems like PHCs. Technical feasibility alone is not enough. Further research is needed to explore what motivates users to accept or reject decentralized identity systems; who is trusted to issue or manage personhood credentials; what concerns users associate with privacy, data ownership, and misuse; and in which contexts PHCs are viewed as necessary versus unwarranted.

As generative and agentic AI continue to blur the boundary between real and synthetic, digital identity will become increasingly foundational for public trust. Understanding how users evaluate these tradeoffs is essential to designing resilient, useful, and beneficial systems that serve the public interest.

Renée DiResta serves on the Tech Policy Press board.

Authors