Landscaping Infrastructures for the Digital Ecosystem

Avani Airan / Nov 8, 2024Today’s digital systems evolve rapidly and cause broad-based impact, leaving regulators to play catch-up. For many years the policies around such technological developments were oriented toward enabling growth and expansion, with governance focused on equity, sustainability, and resilience appearing in regulatory priorities more recently. The emergence of the Internet and other networks of interconnected digital systems, including the Internet of Things, identity systems, and data exchange models, have resulted in additional externalities that significantly affect people, society, markets, and the environment.

In such a context, the prevailing ways of thinking about the technologies and the strategies for governing their impact inadequately account for the full ambit of harms and opportunities within the digital ecosystem. For instance, there has been a focus on regulating the cloud infrastructure market from the lens of privacy and security. Still, there is a gap in deepening market oligopolies and threats to environmental sustainability. More generally, there is a need for a heightened focus on enabling the public interest via digital technologies that respond to the essential role of people alongside regulations that ensure their effective design, operation, and governance.

We believe that adopting an ‘infrastructure’ framing can help address the inadequate governance of the digital ecosystem by opening pathways for improved institutional and community-driven action around the wide-ranging and interlinked impacts of digital technologies. Examining the critical role digital technologies play in society and the reflexive and relational nature of infrastructures can help increase State responsibility in regulating these systems. This approach would strengthen protections against concentrated private control and improve mechanisms for the public to make claims. This can be supported by an inquiry into governance strategies implemented to address the harms and opportunities within traditional physical infrastructures and mapping pathways for adopting similar strategies towards common concerns within novel digital infrastructures.

A parallel exploration of alternative framings that support public accountability systems in the form of localization, participation, or decentralization, as appropriate, emerges as a worthy inquiry to prevent purely top-down governance structures.

Arriving at digital infrastructures

Terminology around ‘infrastructure’ is not new in the digital ecosystem. It is, however, a scattered notion. The term ‘infrastructure’ itself doesn’t have a clearly agreed upon definition, but there are a few commonly recognized characteristics:

- It is critical – The basic services, without which primary, secondary, and tertiary types of production activities cannot function.

- It facilitates further production – A system of interaction of economic agents, ensuring a link between phases of production and consumption.

- It is modular – elements can be combined and adapted for customized solutions that are independently developed but seamlessly integrate into the rest of the ecosystem.

- It is dynamic and has interrelated components – They encompass dynamic networks and assemblages that enable and control flows of goods, people, and information over space.

- It addresses societal needs – The networked assets must be designed to address societal needs, which may be most clearly evidenced in the aftermath of service disruption.

- It generates externalities – Their operation leads to positive and negative externalities, which are the indirect benefits or harms of a project that are complex and difficult to predict.

Thinking infrastructurally enables an understanding of the system as a set of relations, processes, and imaginations. These infrastructural elements are incomplete and unable to function without one other critical component: people. While communities may not fit within the technical notion of infrastructure, there is something to be said for “social infrastructure” that encompasses those involved in the creation and continued functioning of these more technical infrastructures.

Benedict Kingsbury articulates one well-established approach to infrastructural thinking that brings together the technical (the designed and engineered physical and software elements), the social (the human and non-human actants in their intricate relations), and the organizational (the forms of entity, regulatory arrangements, financing, governance, etc.). It is only possible to understand the processes of infrastructure and the consequences or potential of any intervention in infrastructure by fully exploring each of these and their joint interactions and effects.

Looking at these characteristics of infrastructure, we have identified four basic ‘infrastructures’ for the digital ecosystem, namely: data, hardware, the cloud, and standards and protocols. These infrastructures play an important role in the data value chain by enabling the movement, collection, and use of data, as well as in the larger digital ecosystem, for example, the AI value chain. AI models are trained using hardware in the form of microprocessor chips. To meet the extremely high volume of computer power required to train AI systems, developers often use cloud infrastructure such as storage, processing, and even services and tools. This hardware and cloud infrastructure is used in tandem to train AI models using vast amounts of data. Standards and protocols determined by global institutions provide an underlying basis for communication between the various systems at play. All of these different infrastructural elements are harnessed by developer communities to build AI models. However, the governance approach around AI models seems to focus more on the models themselves and the datasets used to train them rather than the enabling inputs.

Unpacking harms and opportunities within digital infrastructures

Identifying the various digital infrastructures and a preliminary inquiry into an institutional approach to their governance presents various harms and opportunities that are missed or inadequately addressed within existing frameworks. In the data infrastructure context, for instance, the EU AI act attempts to protect artists’ IP rights with opt-out mechanisms and recognition of copyright, but concerns remain about its meaningful implementation. Additionally, India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) focus on individual protection but do not account for collective rights. Similarly, with no explicit laws governing cloud computing in most jurisdictions, relevant regulations or executive initiatives tend to focus on optimizing for data access, national security, and sharing (as in the US and India). Existing governance lays inadequate emphasis on the environmental impact of their operation or sovereignty and market concentration-related risks beyond contractual terms.

A deeper study into the common harms or opportunities that appear variedly within the four identified infrastructures surfaces the following larger buckets to consider:

- Sustainability and resilience: Challenges related to the ability of digital infrastructure to endure and adapt in the face of evolving demands, environmental pressures, and natural/artificial systemic shocks.

- Competition and innovation: Risks associated with monopolistic practices, stifling of market diversity, and hindrance to technological advancement within the digital landscape.

- Individual protections and collective rights: Concerns regarding the safeguards to individual economic interests and personal autonomy, as well as the preservation of collective interests in the digital realm.

- National security and sovereignty: Risks posed to the nation's autonomy and security by vulnerabilities in digital infrastructure, including threats of cyberattacks, espionage, or foreign regulatory influence.

- Access and participation: Issues surrounding equitable entry to and engagement with digital resources encompassing both material access and barriers to meaningful involvement in the digital sphere.

Identifying governance approaches within traditional infrastructures and mapping them to digital

The buckets of harms and opportunities identified are common to all four digital infrastructures but play out in specific ways for each. To collate the pathways for institutional strategies on infrastructure governance that must be adapted for appropriate digital contexts, we explore the various executive, judicial, and legislative actions adopted within traditional infrastructures. In our research for this, the five core buckets of harm have been mapped to a conventional infrastructure, each placed within diverse jurisdictional contexts based on relevance, similarities, and access.

For instance, we have examined how executive action (in the form of a government mandate) and legislative action (in the form of the Electricity Act, 2003) in India illustrate different mechanisms for ensuring sustainability (by ensuring compulsory action towards the incorporation of environmentally sustainable practices to reduce long-term harm) and resilience (providing need-based measures that can bolster domestic markets with global support). Similarly, to unpack strategies for addressing core issues around markets, competition, and innovation, we examine executive action in the US, including the Biden administration’s 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy. This order can be seen to prevent vertical integration and promote competition within the market by encouraging the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to prohibit exclusivity arrangements between ISPs and landlords, improve rules for auctioning spectrum, and increase the transparency of broadband pricing.

Beyond executive and legislative action, we also note prominent judicial action against growing monopolies within the telecom sector in the US, where the United States v. AT&T, Civil No. 74-1698 consent decree reviewed state public utility commission decision on interconnection and observed that when appropriate, the commission has broad discretion to establish performance standards to spur service improvements. You can view our research to look at the detailed mapping of governance strategies that address the aforementioned buckets of harms and opportunities in traditional infrastructure.

Placing the “frictions” framing in the governance of digital infrastructures

A review of the strategies adopted for the governance of traditional infrastructures shows that comprehensive frameworks rely on a combination of executive action, which performs a reflexive quick response function, and legislative action, which is a more considered approach to building the right base. At the same time, the judiciary keeps a check on the implementation and refines frameworks post enactment. These strategies can be adapted to open pathways for addressing missing or inadequately considered concerns in the digital context. However, the effectiveness of the strategies adopted would depend on the direction of developments in digital systems and the public's understanding of their impacts on markets and culture.

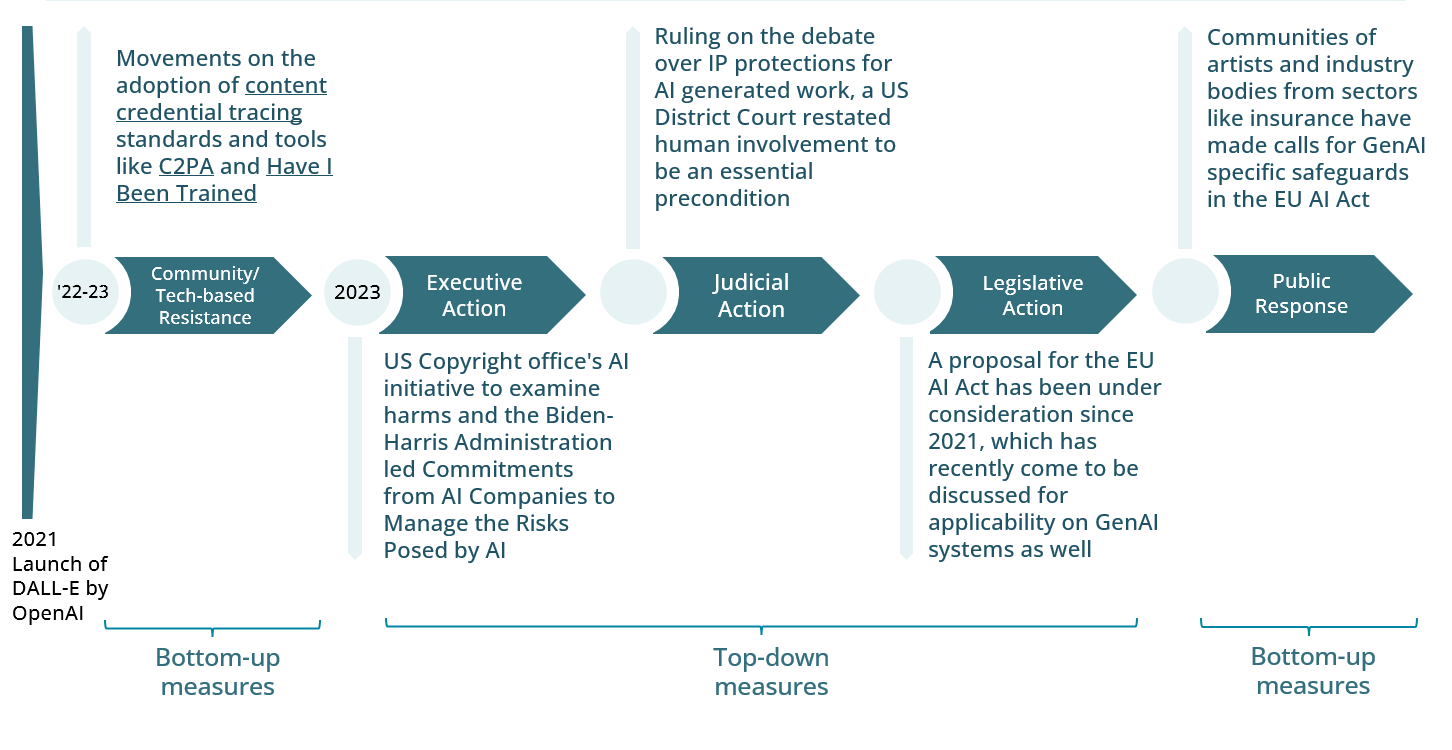

In such a framing, governance of infrastructures can be understood as the result of the friction between the emergence of novel transformative systems, top-down institutional action around their governance, and the society’s response to the changes it introduces. The movements that result from such frictions then translate to top-down policy or bottom-up community initiatives as a process of continuous negotiation between the state and the needs of the society.

This framing can be understood with the example of the regulatory journey around generative AI technologies. Here the frictions in society’s engagement with generative AI, first as an opportunity and then as a disruptor for job markets, has disclosed gaps in its operation and steadily resulted in improved design and governance.

The mechanisms we have explored in the preceding sections are all top-down mechanisms originating in the State. The operation of these mechanisms in an equitable and just manner is dependent on embedded transparency and accountability related measures around state functions. As is evident from the governance journey around generative AI so far, building a robust governance approach to digital infrastructure also requires that power is equally vested in the public, such that the systems of engagement empower them to hold both private and State actors accountable to act in greater public interest.

To this end, we must consider bottom-up governance mechanisms that directly speak to the needs of the affected communities. In the digital ecosystem, we have already witnessed a number of technology and community initiatives come about in response to the gaps that arose in the deployment of generative AI tools in various sectors, including creative industries, IT, and cultural preservation. For instance, Glaze came about in response to the threat of IP infringement, and it protects against style mimicry by altering artwork such that it appears to be a different style to an AI model while appearing unchanged to the human eye.

Bottom-up governance also often takes the form of community movements as initiatives to fill gaps to resist the harms caused by novel technologies. To that end, the undertakings of Te Hiku Media, which works as a Māori language archival and revitalization-focused organization, provide notable instantiations. In particular, their Data License spells out the ground rules for future collaborations on traditional knowledge based on the Māori principle of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship. Community movements to this end can also come from less cohesively formed communities, such as the users of Stack Overflow, where community members altered or deleted their posts and comments in protest, arguing that this steals the labor of the users who contributed to the platform.

These efforts make it evident that enabling people to voice their concerns post-deployment and involving communities in the design and implementation of digital infrastructures with appropriate participatory mechanisms can lead to socially relevant and responsive infrastructures.

Realizing the infrastructure framing

Our research so far has shown that placing digital systems within an infrastructure framing can be instrumental in helping us identify the essential roles they play today in addressing societal needs. Further, the reflexive nature of such infrastructural networks enables the adoption of a comprehensive approach to their governance that accounts for the various harms and opportunities that are present within relevant digital infrastructures. In such a context, to realize the full potential of the benefits these systems can afford for society at large, it is essential to:

- Be intentional about orchestrating an enabling environment for bottom-up community movements to thrive. Particularly in the context of digital technologies, the fast pace of transformative developments makes it burdensome for institutional action to keep up with top-down mechanisms alone. Additionally, as people use, operate, and define digital infrastructures, enabling localized channels for people to engage with the governance of these systems can lead to the creation of better, more contextually relevant and responsive infrastructures that run smoothly and sustainably.

- Assist top-down institutional mechanisms by comprehensively addressing the full spectrum of harms and opportunities that arise within infrastructures through appropriate strategies on governance. In this process, it becomes essential to consider the externalities that the widely interlinked infrastructures generate, and balance business, social, and environmental interests equally.

- Enable global solidarity in the operation and governance of these infrastructures. Presently, a significant share of control on digital infrastructures that operate globally is concentrated in the global north. This has resulted in major power asymmetries for global south countries that both affect the operation of these technologies and are affected by them in significant ways. Global south countries provide huge markets to deploy digital technologies at scale, with large parts of the population in these countries relying on access to the technology that is frequently housed and controlled within global north majority nations. On the flip side, the owners and operators of these systems rely on human resources from global south countries for tasks requiring intensive human labor, such as data labeling or content moderation. Considering the deep interdependencies of countries on each other and the highly interlinked impact of these technologies across the globe, it is important to consider how the sovereignty of nations can be secured and how solidarity can be built to enable equitable benefits for all.

At its core, adopting the infrastructure framing for digital systems allows us to reframe the governance approach to break the concentration of power. By recognizing the critical societal functions they perform and understanding the nature of their operations accurately, we can begin to rearrange the accountability structures and distribute control from private hands and distribute it towards the State and the public while being mindful of global sensitivities that emerge. To realize the potential of such digital infrastructures while accounting for the gaps and harms in their operation, some solutions can be identified based on learnings from similarly placed traditional infrastructures. In translating such strategies for the digital context and orienting them for the peculiarities of this new form of infrastructures, certain questions emerge for further research:

- What are the necessary frictions that emerge within current governance frameworks for digital technologies that primarily rely on top-down mechanisms?

- How can we understand the political economy around the operation of these digital infrastructures and decentralize the concentrated power structures meaningfully?

- How can we enable effective participation from the people and communities that affect and are affected by these technologies, to enable constructive bottom-up action that can address local needs?

Ultimately, framing digital systems as critical infrastructures emphasizes their societal impact and the need for robust, inclusive governance. Balancing top-down regulatory actions with community-driven initiatives enables a more resilient, equitable digital ecosystem. This approach fosters global collaboration and empowers people, ensuring sustainable and fair digital technologies serve the public good.

Authors