KOSA's Path Forward: Distinguishing Design from Content to Maintain Free Speech Protections

Caitlin Burke, Christina Lee, Jennifer King / Oct 1, 2024

On September 18, 2024 the House Energy and Commerce Committee hosted a full committee markup of 16 bills, including The Kids Online Safety Act and the Children and Teens' Online Privacy Protection Act.

On September 18th, the US House Energy & Commerce Committee advanced a pair of child online safety and privacy bills for consideration by the full House after the Senate passed the combined measure in a 91-3 vote in July. As Congress comes closer to passing KOSA and COPPA 2.0 (together “KOSPA”), the debate over whether the KOSA portion of the joint proposal chills online free expression continues. Proponents of KOSA argue that it is about design and not content and would consequently not harm First Amendment rights. Opponents argue that KOSA would allow tech companies, like social media companies, to censor protected speech because it would make companies liable for harmful content. News coverage reports that KOSA would make platforms liable for bad content.

We argue that KOSA only needs a minor change to mitigate these concerns. Both the version of KOSA that passed the Senate and the version advanced to the House floor include “personalized recommendation systems” (i.e., the mechanism that determines what content the user will be served up) in its definition of design features. However, as we explain below, content algorithms and design features are two related but distinct components of digital products. And importantly, while content algorithms directly implicate First Amendment-protected speech, design features, properly understood, do not.

By striking “personalized recommendation systems” from the definition of “design features,” KOSA would not chill free speech because product design and user-generated content (UGC) represent two entirely different spheres of a digital product. Applying a human-computer interaction lens to the issue, we aim to clarify how removing design features and affordances, like the infinite scroll feature that allows users to consume content endlessly, would not impair a young person’s ability to search for or discover meaningful content online. In short, creating legislative mandates for companies to pare down features would – in essence – return the user experience to an experience with increased friction that would discourage prolonged use.

This distinction reinforces Section 230 protections and First Amendment rights. By distinguishing between content and design, Section 230 may exist independently and harmoniously with KOSA. Social media companies would still enjoy freedom from civil liability for content moderation or harm based on the hosting of third-party content. This distinction also aligns KOSA with the recent Supreme Court decision in Moody v. NetChoice, which held that a social media platform’s algorithmic curation amounts to editorial judgment and receives First Amendment protection.

UGC, product design, and content algorithms work together to create the social media user experience, but they are distinct pieces of a social media platform. Courts should treat them as such. We tackle this complex issue by identifying what KOSA does; how digital products are built; why UGC, product design, and content algorithms are unique; and how KOSA can help to clarify this distinction. We demonstrate how design-based online safety proposals, like KOSA, correctly aim to interrupt the addiction “loop” on social media platforms by targeting product design.

We end with a legislative and constitutional proposal showing that it is possible to protect consumers online while simultaneously fostering technological innovation.

What KOSA Does

The House Energy and Commerce Committee advanced House versions of the bill in September. Like the prior Senate version passed in July, this latest House version would create a duty of care standard for covered platforms. It also encourages platforms to create non-harmful product features and affordances.

- Duty of Care: KOSA would require a covered platform to reasonably prevent and mitigate harm to minors in its creation and implementation of design features. Harms include compulsive usage.

- Design Mandates: KOSA would also create safeguards for minors that connect to product design. For example, it would require a platform to limit design features like infinite scrolling that encourage “the frequency of visits to the covered platform or time spent on the covered platform.” As noted above, KOSA includes the control of “personalized recommendation systems” with the description of safeguards.

How Digital Advertising Works

By creating product design mandates, KOSA would mostly impact how products are designed instead of what content is available to users. This difference becomes clear when reviewing how digital products are built to support targeted advertising.

Social media products like TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat are designed to collect as much data as possible from users to support a targeted advertising revenue model. Users interact (or engage) with social media and provide the platform with behavioral data (likes, blocks, click-throughs, follows, etc.). Social media companies sell advertisers access to their users through their ad-targeting platforms so that advertisers may target users with increased effectiveness. The social connectivity enabled by a social media platform is not the foundation of its business model; the true commodity for social media companies is the data generated by user interaction. The more a user engages with a platform, the more data they produce and the more data the company can use to finely tune their targeting capabilities to advertisers.

Social media companies are consequently incentivized to keep users on their platforms for as long as possible and as frequently as possible so that they can produce more data. Prolonged “user engagement” results in more data collected as each click and tap helps to form a unique behavioral profile of each user, allowing for precise ad targeting.

There are three main components of a social media product that support this revenue model: user-generated content (UGC), the algorithm, and the user interface/user experience (UI/UX). At a very high level, users generate content for the platform by producing, for example, a video for TikTok or images for Instagram. When a user publishes a piece of content, it is uploaded into a repository. At that stage, each piece of content is non-hierarchical; content is generally not ranked according to a user’s preferences. Social media companies might infer preferences at an early stage based on criteria like gender or age, but content preferences evolve as a user interacts with the platform.

To access the uploaded content, a user can engage with the platform in two ways: they may search for content via the search bar, or they can view recommendations in their content “stream” (Meta’s “News Feed,” TikTok’s “For You Page,” or YouTube’s “Next Up,” e.g.).

If the user chooses to open their content stream, a content algorithm “lifts” content from the repository, pushing it into the stream. Users may interact with the content through various UI/UX features and affordances. These features and affordances include comments, “like” buttons (such as a heart or thumbs up), or follow buttons. After the user interacts with a piece of content, the content algorithm incorporates this feedback. The next time the content algorithm goes to “lift” content from the repository, it will know that the user prefers, for example, dog videos over cat videos. The content stream, therefore, becomes more personalized over time as the user provides more information to the content algorithm. There are additional ways that content gets aggregated across the platform, like hashtags containing trends, but the method described above provides the foundation for most social media systems.

Why Targeted Advertising Has Caused Harm & Why Design is Distinct from Content

Research demonstrates that negative effects, like problematic usage, come from this loop.

Social media companies use triggers like the infinite scroll feature to incite a user to action. A personalized video, like a dog video, is the reward for the action of pulling the scroll down like a slot-machine lever, encouraging further action. Consequently, the feature – the infinite scroll – creates the incentive for overuse. If TikTok were to remove the infinite scroll feature, users could still find content through, for example, search. They might also view content through a different interface that would not encourage endless scrolling. Introducing a friction point, such as receiving a request from TikTok to pause viewing after fifteen videos (for example, “You’ve watched 15 videos; would you like to continue?”), is a small interaction design change that would interrupt the dopamine flow of endless scrolling, encouraging more moderate platform use and creating more digital friction.

As noted above, interface features control how a user interacts with a platform. They provide the foundation for the feedback loop between the content algorithm, personalization, and use. When users watch, hover, or scroll to pull down videos in their TikTok infinite scroll, they provide behavioral data points to the algorithm, influencing the types of content they are served. However, interface features do not influence whether content is ultimately available to them. Users will still see the videos they prefer in their content stream, and they may search for this content. They will not, however, spend as much time on a platform if the feedback loop is interrupted through friction.

The overall user interface design, and specifically the interaction design that affords the use of the platform, exists in an entirely separate product area from the content algorithm and UGC. Like grease on wheels, interface design improves a product’s usability. It does not connect to or relate to whether the content is available to the user or how the user may access this content. Interaction design features, such as swiping from left to right on a mobile device to advance a screen, merely assist users in interacting with content.

How KOSA (Mostly) Succeeds

It is exactly this form of interaction that KOSA targets. A legislative mandate requiring non-harmful product features will not chill free speech because product features are about use, not content. To drill this point in even further, social media companies have launched and rolled back features time and time again. In 2021, for example, Instagram retired the “swipe up” feature, which allowed users to add a link in “Stories” accessible by swiping up on their screen. Content was freely available on Instagram before and after the feature was removed. The removal or addition of design features does not change digital free expression.

KOSA, however, conflates interaction design with the content algorithm in its current iteration. Under the definition of “design feature,” KOSA notes that design features may include “personalized recommendation systems.” As demonstrated above, the personalized recommendation system includes a collaboration between the UCG, the content algorithm, and UX/UI features. This definition is too broad and should be removed to clarify that product features are simply that – features.

We thus recommend striking this portion of the text so that KOSA strictly focuses on interface design. By removing “personalized recommendation systems,” KOSA focuses almost explicitly on interaction design within the interface, not the content algorithm. This modification would also coordinate KOSA with the recent Supreme Court decision in Moody v. NetChoice, which held that social media platforms’ content algorithms are “editorial choices” afforded First Amendment protection.

Section 230, First Amendment, and KOSA

Understanding this distinction between product design and content actually clarifies how Section 230 and First Amendment defenses might be properly applied.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act protects social media companies from liability for harm resulting from UGC. It also protects a social media company’s ability to moderate content. Since it was passed, the Internet has changed in profound ways, and in recent years, there have been a number of attempts to reform Section 230. Some reform proposals have advocated for adding more carve-outs for specific types of harm to Section 230 immunity. FOSTA-SESTA, the only reform to Section 230 to have passed in recent history, was such an amendment; it added sex trafficking to the list of carve-outs. Unfortunately, FOSTA-SESTA, rather than curbing trafficking as it was intended to do, only increased the dangers faced by sex workers, becoming a cautionary tale told to those who attempt to amend Section 230.

Another important aspect of modern social media platforms is their curation of content for users. Today’s social media is not a passive conduit of information; most platforms have personalized feeds and recommendations that serve endless streams of content. In July 2024, the Supreme Court held in Moody v. NetChoice that the algorithmic curation of such feeds amounts to “editorial control” protected by the platforms’ First Amendment rights.

The line between UGC and the platform’s speech is an area that is thus currently hotly debated. A three-judge panel in the Third Circuit recently handed down an opinion stating where the line is in Anderson v. Tiktok.

In the case, a 10-year-old was shown a video on her TikTok “For You Page” of the “Blackout Challenge,” which encourages individuals to choke themselves with items such as belts or purse strings until they pass out. She decided to imitate the behavior shown in the video, which ultimately resulted in her death. The majority of the panel held that the Supreme Court’s decision in Moody meant that TikTok’s “For You Page” was TikTok’s first-party speech, not third-party content. Therefore, it was not protected under Section 230. This decision, which broke from the prevailing view of what Section 230 protects, is controversial, drawing praise from some and sharp criticism from others. This saga is far from over; TikTok is expected to request a rehearing en banc. Nevertheless, the holding indicates that content algorithms may not be protected under Section 230 because they amount to editorial expression by the platform, as the Supreme Court indicated in Moody. Given the recent Supreme Court precedent, more cases may follow this line of thinking, demonstrating the need to rethink Section 230 protections for content algorithms.

No matter where the boundary of Section 230 protection for content curation ends up being drawn, there will still be aspects of social media platforms that are neither UGC nor the platform’s own First Amendment-protected activities. KOSA, with the amendment we propose, focuses on such aspects by seeking to regulate potential harms caused by design features, which are, as discussed above, distinct from UGC or how social media companies choose to curate content. In this sense, KOSA reinforces protections afforded by Section 230 and the First Amendment because it makes clear that interaction design is the cause of user harm. KOSA can clarify the distinction between UGC, interaction design, and the content algorithm, particularly if the algorithm falls under the province of the First Amendment.

Consider a hypothetical lawsuit against a social media platform in a world where KOSA, with its definition of “design feature” properly narrowed, has passed.

- If the theory of harm is that the content another user uploaded to the platform was the source of harm, and the platform is responsible because it hosts this content, then Section 230 protections would apply.

- If the theory of harm in a tort suit relates to the algorithmic curation of content, then the social media platform can claim a First Amendment defense over its content algorithm. Similarly, a social media company may argue a First Amendment right to algorithmic curation in response to state action that attempts to constrain the content algorithm.

- If the theory of harm is that a certain interaction design feature, like the infinite scroll feature, led to a child engaging in problematic use of the platform, then KOSA would come into play. If KOSA were to be enacted with the narrowed definition of design that we propose, then, hopefully, these types of harm would be mitigated through FTC enforcement. By disrupting the addiction loop through interaction design changes, harms that come from, for example, trends like the “Blackout Challenge,” might be ameliorated as users will not see this content as often and with such frequency.

By decoupling content and design, legislation can mitigate harms caused by design without impinging on Section 230 immunity or First Amendment protections afforded to platforms.

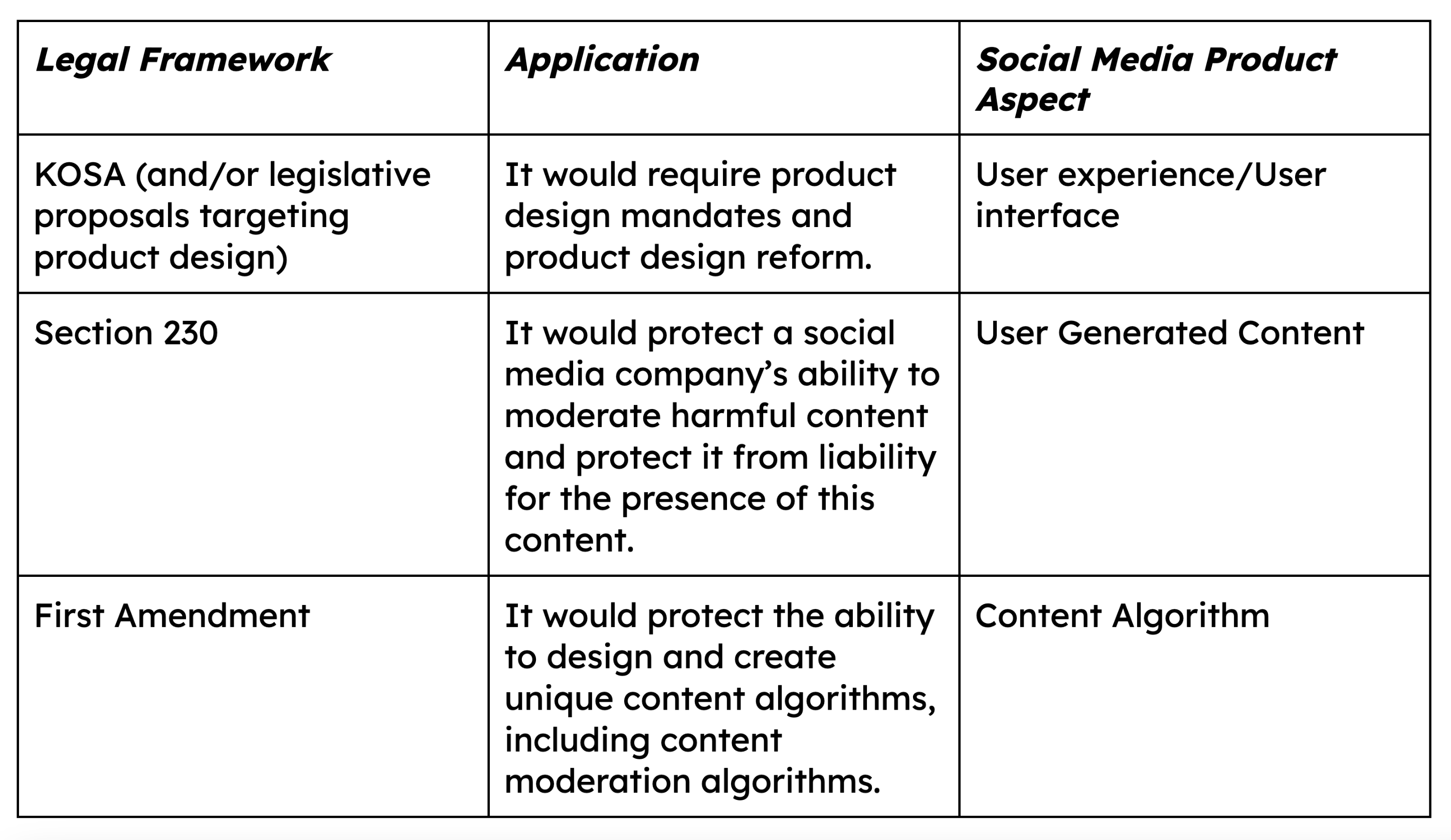

We, therefore, propose a three-part legislative and constitutional framework that would harmonize KOSA with Section 230 and the First Amendment:

Framework outline.

Conclusion

Legislation targeting design might make social media less compelling, but it won’t chill free expression. By targeting interface design, KOSA can clarify the difference between UX/UI, UGC, and the content algorithm. All three components work together to create the social media experience, but they should be considered, under the law, as related but distinct. By clarifying how digital products are built and how these three components differ, we can mitigate harms caused by design features while preventing content censorship under design regulation's guise. Notably, the framework proposed above is also malleable: if social media companies must create an experience with more friction for minors, then they may also be encouraged to allow adults to “opt-in” to a friction-full experience, as well. Children turning 18 could elect to keep their social media experience friction-full. In other words, if a user doesn’t want to enter the casino, they shouldn’t have to.

We acknowledge that in certain cases, the lines delineating these three components will not be clear, as evidenced by Anderson. However, certain aspects of social media are distinctly tied to interaction design rather than content. KOSA, properly narrowed to target only design features, can be used to target the harms that come from design features like infinite scroll. This would not impinge on the First Amendment or Section 230 protections.

If free expression existed in the 2000s when social media companies like Meta (then Facebook) were static and feature-free, it would still be available under a framework that eliminates features that cause harm. An approach that applies legislative and constitutional rights together with KOSA creates a balanced architecture that accounts for both the social media actor and the consumer.

Authors