Inoculating Against Climate Mis- and Disinformation: Case Studies from the US and the UK

Elyse Martin, Florencia Lujani / Jun 4, 2024

December 3, 2023. A demonstrator in Brussels, Belgium holds a placard during a climate protest coinciding with COP28 being held in Dubai. Alexandros Michailidis/Shutterstock.

In the battle against misinformation, one response has started to generate some promising data: inoculation. This practice treats misinformation like a virus: by exposing vulnerable populations to a ‘micro-dose’ of misinformation, explaining that what they have just read was inaccurate, and then offering a correction. Theoretically, this practice will enable people to better recognize misinformation when they see it in the wild. But does inoculation work in practice, or just in theory?

Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and ACT Climate Labs, both member organizations of Climate Action Against Disinformation, recently put inoculation messaging to the test in the US and the UK. Their findings are bolstered by research from the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) and Dewey Square Group, who recently reviewed the state of the field. The results indicate that inoculation can be very effective, but only if done right.

The US example

In March, EDF worked with YouGov to field a survey exploring different ways to change peoples’ beliefs around climate change, with a sample of 1,105 self-identified, registered US voters of any partisan affiliation and an additional sample of 1,016 voters who identified only as Republicans and Independents. Republicans and Independents were sampled in order to better understand how right and center voters perceive climate misinformation, what messaging might persuade them on climate change, and what interventions against misinformation may be most effective for these voters.

The survey asked participants to evaluate the accuracy of two common disinformation statements about climate change, the “Money Grab Claim” and the “Lack of Consensus Claim”:

- The Money Grab Claim: “Elites have invested in clean energy companies. They stand to lose a lot of money if global warming is revealed to be a hoax. They also bribe climate scientists to fix the data so that they are able to secure their financial investment in clean energy.”

- The Lack of Consensus Claim: “Scientists argue that observed warming trends associated with climate change are a natural variability and human activity is not a significant factor.”

Participants were randomly assigned to see one of three different corrections: a scientific statement demonstrating how these claims were false, a quote from a Republican politician on the reality of climate change, and a control group answer simply stating the two statements are climate change misinformation. The most effective of these three was, surprisingly, the scientific response citing specific case studies:

The two statements you were presented with are commonly spread pieces of misinformation about climate change. There is a unanimous consensus among scientists that climate change is real, and the result of human activity. The influence of human activity on the warming of the climate system is an established fact across scientific dominions. [NASA, IPCC Report]. If elites were bribing scientists to “fix their data’’ it would be challenging to maintain such widespread consensus. Scientific analysis taken from natural sources like ice cores, rocks, and tree rings, and with modern equipment like satellites and instruments all show the signs of a changing climate. Climate research is funded by a diverse variety of sources including government grants, non-profit organizations and foundations. Many scientists receive funding from multiple sources, reducing the ability for undue influence by a single actor.

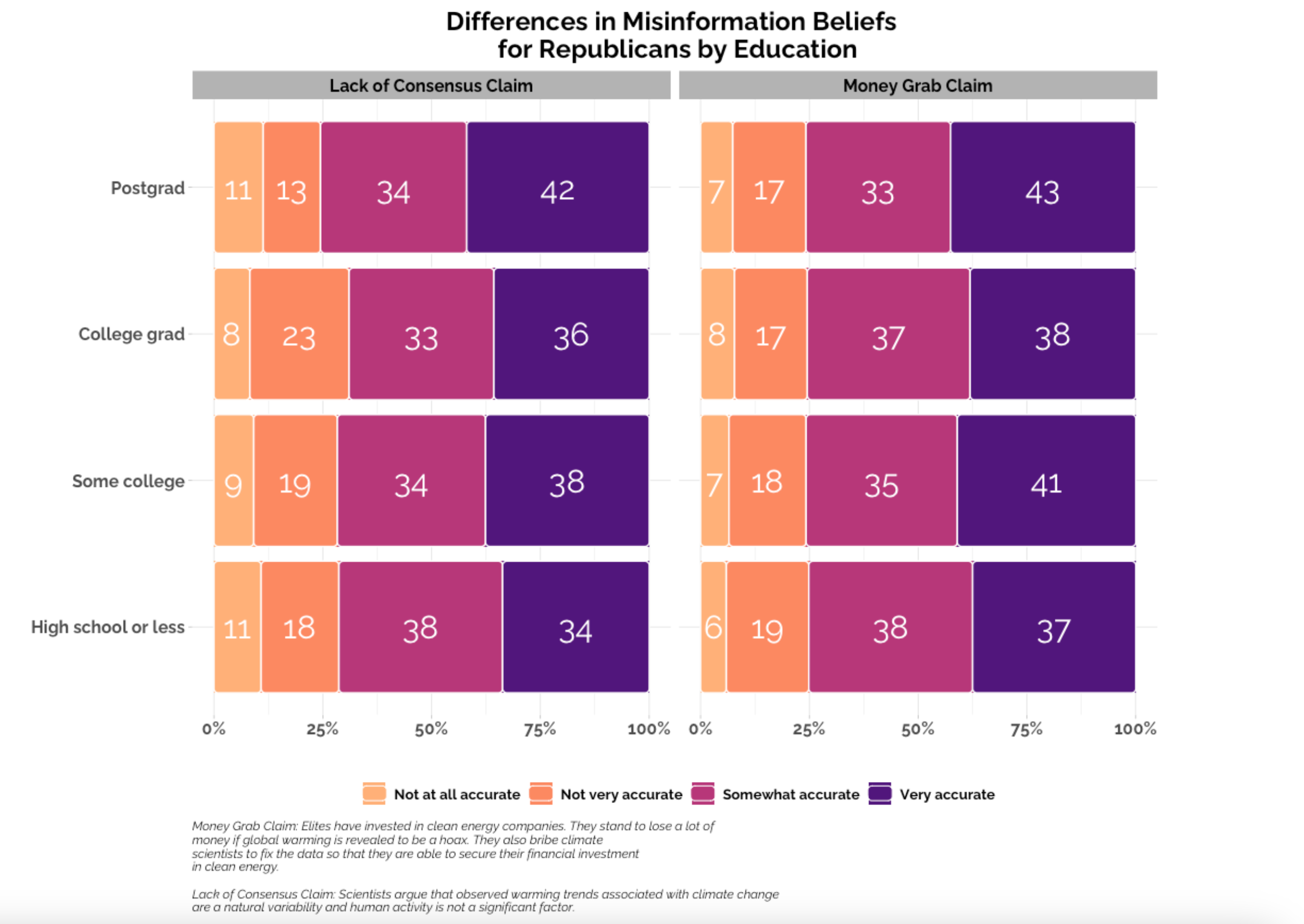

In the survey, we found that a majority of Republicans are more likely to view climate misinformation claims as accurate, even across educational backgrounds. As can be seen in the chart below, more than 65% of Republicans with college degrees assessed the presented misinformation claims as accurate. For voters who believed in conspiracy theories, the science-centric statements were the most consistently effective at mitigating belief in misinformation. This holds for Republicans, who also showed an increased ability to evaluate the claims as inaccurate after reading the scientific statement correction.

A majority of Republicans across educational backgrounds evaluate misinformation claims as accurate, per a survey on behalf of The Environmental Defense Fund conducted by YouGov Blue fielded from February 5 to February 13, 2024. Source

Our results contribute to the growing body of work showing that factual corrections can improve the accuracy of beliefs, when presented with care. The results also show that relatively brief and clear statements of fact may significantly persuade some portions of the electorate to reconsider their views, even those who hold strong beliefs in climate misinformation.

Additionally, this research contributes to the debate on whether fact-based corrections or values-based messaging that appeals to beliefs in line with specific ideals or ideologies are the most effective tools for combating climate misinformation. The findings suggest both a pathway forward and a need for further testing. Was the counter-messaging effective because of its cheerful, authoritative tone rather than its content? Was it effective because these were old and common pieces of disinformation that people had heard about already? EDF’s plan is to continue testing and sharing our successes and failures in combating climate misinformation to build the field’s understanding of the most effective inoculations against misinformation, particularly for those most vulnerable to believe false or misleading claims.

The UK example

ACT Climate Labs took a complementary approach to EDF’s, using advertising to reduce the influence of misinformation on people’s attitudes toward climate issues. Instead of exposing people to a micro-dose of misinformation, ACT monitors misinformation narratives to identify which ones are already reaching “persuadable” audiences, and then creates advertising campaigns to disseminate inoculation messages. This data-first approach means that the advertising campaigns don't need to further expose people to misinformation, and the campaign can just focus on delivering one key message that is pro-climate action.

This approach has demonstrated strong results, and ACT advertising campaigns have all been able to diminish the impact of misinformation as well as shift attitudes and opinions around climate issues.

One of these campaigns was delivered in collaboration with UK-based charity Possible. Possible wanted to launch a new initiative to campaign for “Car-Free Cities,” arguing for fewer cars in the streets in Birmingham, England. Car and traffic reduction plans have been central to recent targeted misinformation campaigns, ranging from concerns with local planning all the way to accusations of globalist plots. Some conspiracy theories position the popular 15-minute city planning concept as part of a wider plot to enforce climate lockdowns, where residents’ movements will be restricted. This leverages a fear of the restriction of freedom, and persuadables are at risk of believing such conspiracies and misinformation if they see enough of it go unchallenged.

The ACT campaign focused on showing the benefits of having fewer cars in the streets to local residents in Birmingham: better air, health, communities, and spaces. These key messages were delivered by trusted people in the local community, and the ads didn’t mention “car-free” or climate change topics. Instead, we let our local cast of trusted community members speak for themselves in their own words, and their quotes made the headlines of the ads to increase relatability and relevance.

The campaign was successful in changing attitudes toward car use in a town called Handsworth. We saw a massive uplift of 40% in people agreeing with the statement central to the campaign: “Neighborhoods should be for people not cars.” People were also more receptive to the idea that “having fewer cars is a good idea”—from 61% agreement before to 70% after the campaign, a nearly 15% uplift. Most importantly, our campaign inspired real behavior change. Those who recalled the campaign in the West Midlands used their car 5% less post-campaign. When it comes to public transport, 24% are taking the bus more often and 18% the train. Looking at how this behavior change is likely to be sustained in the future, those who related to the campaign were 40% more likely to continue this behavior in the future, and 66% were likely to change some behaviors to tackle climate change in the next six months.

An ad campaign in favor of mass transit. Source: ACT Climate Labs

Research review

Our findings echo the review by the DDIA and Dewey Square, which found that “inoculation is one of the most promising theories for countering disinformation.” They showed that “inoculation works, that it works across ideologies—even with extremist content—and that it can work at scale, if implemented correctly and by the right actors and entities.” The study found that “refutation messaging needs strong ‘Accuracy Prompts’ to spur the users to critical thinking and to prioritize the accuracy of what they are seeing and sharing,” which reinforces EDF’s learnings. They also say that “inoculation initiatives must begin early, before the disinformation tactic or narrative being targeted has had the chance to spread widely. Inoculation messaging should be timed around key strategic moments, to have maximum impact when it’s needed most,” echoing ACT’s learnings.

However, one important and challenging point they found is that some inoculation effects can fade quickly, lasting “somewhere between two weeks to months,” so the recommendation is that ongoing ‘booster’ messaging should reinforce inoculation and resources should be held back till the last possible moment before the deadline for action.

Conclusion

Inoculation efforts can and do persuade audiences in surveys and in the field, but our two case studies also raise questions as to the best ways to target persuadables and the best ways to convince them to be on their guard. The good news is that this method does work, in the field and in research, even against audiences inclined to believe disinformation, if delivered by the right messenger at the right time.

However, this can be tricky to implement in the current climate of very targeted misinformation aimed at specific communities, or specific ideological groups. ACT’s example suggests that a messenger who is part of the target group can be very persuasive, and EDF’s example suggests that the tone and factual content of the correction may be the key to persuading audiences. What would the effect be if both methods were tested against each other, or combined? The Dewey Square research also suggests many new avenues for exploration, such as a study of a sustained inoculation campaign over time, with particular focus on how timing impacts the efficacy of inoculation messaging. There is likewise much to explore in the different benefits of exposing audiences to microdoses of misinformation, or avoiding addressing misinformation altogether to focus on delivering one corrective counter-narrative.

The two studies and the related empirical research show that this theory works. The question now is not “will this work in the field?” but “how should we implement it?” This field is ripe for deeper and more thorough investigations in the practicalities of implementing inoculation messaging against disinformation.

Authors