In Weak Job Market, Middle Managers Increasingly Forced to Feign AI Success

Diana Enriquez / Jan 23, 2026Diana Enriquez is an associate principal in Redstone Strategy Group’s New York City office, where she develops technology strategy, design, and implementations to help foundations, nonprofits, and governments strengthen their impact.

Isolation by Kathryn Conrad & Digit / Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

As a sociologist and user experience designer early in my career, I studied efforts to “pre-automate” routine work at scale through Amazon and Uber. My doctoral research at Princeton focused on the automation and outsourcing of labor, and how these efforts reshape firms and production processes. Now, my latest research confirms that many of the trends I’ve seen emerge among marginalized gig workers are cascading across the broader workforce. In this environment, middle managers are increasingly being managed by automated systems. But more and more, they are also being asked to justify AI hype.

Interviews I conducted with 50 middle managers over the last 8 months suggest that the perfect storm of a weak job market and pressure to align with an “AI-optimist” mindset demanded by executives means they are responsible for keeping up the illusion of an ultra-successful AI roll out. I started the interviews in Spring 2025 as a follow up to my Pre-Automation studies with gig workers - it was wild to me to see how many of the problems we saw emerge with delivery workers at scale show up now in corporate America and I couldn’t let go of the question: have we learned anything about scaling automation, or will I see more of the same challenges? When I ask middle managers how they are doing, I keep hearing a similar story: the weak job market means they feel more pressure to hold onto their jobs at all costs, accepting more shifts and vocalizing fewer complaints.

In this precarious situation, middle managers often appease leadership requests to implement AI automation even when there is limited value in it, pretending that their error-free draft was written by an AI tool that actually failed to deliver them a single coherent copy. They push harder to do more work with less time because the job market now demands they demonstrate familiarity with AI to align with the company’s evolving brand and complete work at the expected level of quality. The result is increased employee anxiety, burnout, and limits on productivity rather than gains. And it’s not just my 50 interviewees — a recent survey of white collar workers referenced in the Wall Street Journal found that the “gulf between senior executives’ and workers’ actual experience with generative AI is vast,” with executives reporting much higher efficacy than workers.

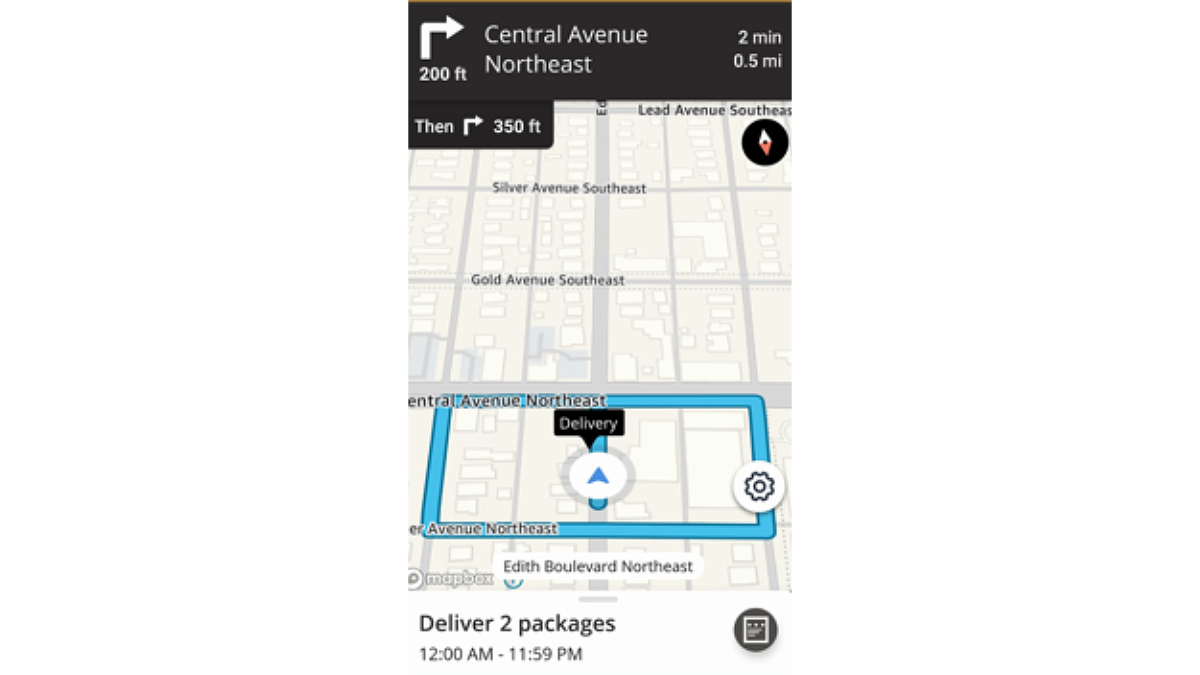

As I learned from my prior research on gig labor, workers in pre-automated environments regularly run into an impossible choice: do I finish the task even if I have to override the technology (and break employer rules by doing so), or do I follow the rules and fail to complete the task? A key problem we identified in our earlier studies on automated and pre-automated work environments was rigid and frequently incorrect instructions demanded by an automated tool working in a real environment with messy variables the tool could not account for. For example, workers often received driving instructions for the most efficient route that ignored road closures or proposed bridges that are not designed for cars. In 2019, one Amazon driver in the employee chat posted a route recommendation to deliver a package that offered no entry and no exit. He asked, “Do I ignore the instructions and deliver the package, but get an automatic citation for breaking the route on my file? Or should I drive in circles for the next 5 hours and never deliver the package?” Other drivers responded with nearly a hundred similar challenges in the thread over the next week.

Photo from Fall 2019 shared by a delivery worker depicting a route with no end.

In these work environments, people are seen as problems to be solved and the automation is assumed to be correct because of its perceived rationality. Automated tools employing AI are often perceived as grounded in math, computer science, and big data that is far more easy to read on a dashboard than a typical employee. And these systems are constantly tracking activity, which also means senior leadership can track how actively their teams use the AI. Now, middle managers face mounting pressure to either become “AI literate” and demonstrate daily active use, even when it does not serve them or their teams. The AI myth is further perpetuated by this job market pressure. Some of the folks I interviewed about the challenges they face with automation feel the need to post about their ‘exciting’ applications of AI at work on LinkedIn.

Designing a fully automated system is not only hard, but often short sighted. A world where all work is automated to some degree is likely one where fewer people have work. And since most of these automated systems rely on the existence of consumers, reduced employment rates will have negative long-term implications for the companies themselves. Moreover, if everyone is making their way through frequently broken automated systems with zero ability to repair them or interact with them effectively, who is left to buy from/use these services? Some platform builders surface vague mentions of universal basic income, but these same builders actively work to cut taxes, diminish public services, and end various support mechanisms for families struggling in the current economy.

I find comfort in that as much as the AI hype wants us to believe everything is changing and we’ve lost our agency, many basic design rules that center people and clear purpose remain the same. The technology tools that are helping people succeed are those designed with individuals, rather than massive profits, in mind. They are fit for purpose, the data they consume is intentional, and there is an opportunity for workers to co-design their methods and outputs. Such systems have override features for moments when the technology inevitably breaks, and employees are not penalized for using them. There are opportunities for the people using it to evolve the technology as it matures. The situations with routine failures are those where designs are black boxed and imposed on the people forced to co-exist with them.

A better future is one where workers have tools they can crack open, adapt, and customize to help them thrive—which is at odds with the current monopoly-or-bust platform model. I have always admired how scrappy and creative every gig worker I interviewed was, especially as they navigated their automated world. It was a mostly broken and punishing world, but they found ways to work effectively with their technology, dodge the nonsensical parts of the technology’s demands, and build community despite typically working in isolation. I now admire how the middle managers I interview now are as committed to keeping their teams hopeful amid the mounting challenges of the 2026 economy and uncertainty in the world at large. What will turn this moment around is taking the pieces of automated tools that work well and building them with an intention to support, rather than replace, workers. As I design automated tools for myself, I first ask, “What will help my teams?” The answer is often much simpler and clearer in its design than the blackboxes of AI products. And we focus on building in the levers and opportunities to customize they need to thrive.

Governments, unions and the broader public are making longer bets on the health of their communities. I want to see what kind of future they want to design. I am encouraged by the politicians running campaigns on “right to repair” that demand enough design transparency and opportunities to override or customize tools so that we can make them work for our needs. The public needs to have a clearer voice on what “good” looks like and the space to make long bets on what keeps society healthy and functioning. To counter AI hype, companies must have a clearer commitment to human-centered design and outcomes that benefit rather than replace workers, and policymakers must pursue interventions that protect labor, from the front lines to middle management and beyond.

Authors