How the House Judiciary GOP Misread Europe's €120 million X Decision

Dean Jackson, Berin Szóka / Feb 3, 2026Dean Jackson is a contributing editor at Tech Policy Press. Berin Szóka is President of TechFreedom, a think tank dedicated to global tech policy.

Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH) speaks with then White House advisor and billionaire tech CEO Elon Musk ahead of the NCAA Division I Wrestling Championship on March 22, 2025 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo by Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images)

On January 28, the House Judiciary Republican’s official X account posted a thread alleging that the rationale for the European Commission’s €120 million fine against X, the first ever fine under the Digital Services Act (DSA), was “weak and a pretext for censorship.” On February 3, it reiterated its criticisms of the EU decision in a 160-page report, its second on the theme of European regulation.

Notably, the House Judiciary GOP’s initial thread included a link to the previously unpublished document laying out the Commission’s rationale for the fine. As a result, close readers can draw their own conclusions about which argument has greater merit: the Judiciary Committee's report, or the Commission’s decision. Below, we assess the House Judiciary Republicans’ criticisms of the Commission’s fine against X based on a close reading of the Commission’s own words.

How to parse the EU decision

In its decision to fine X, the Commission identified three distinct areas of the company’s noncompliance with the DSA. Despite Republican claims to the contrary, the Commission’s enforcement of the DSA must be content-agnostic because, as more than thirty legal experts on the DSA wrote in a letter to the Judiciary Committee in September, the DSA does not give the Commission the power to punish lawful speech and it does not, itself, make any speech unlawful. As such, the three areas of noncompliance do not relate to content at all. They are:

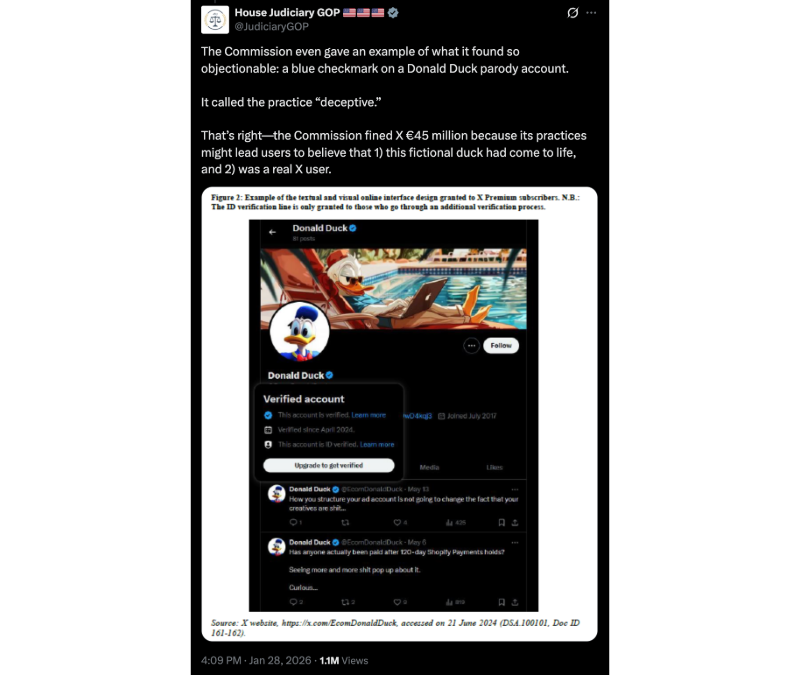

- Whether or not the decision to grant verified account status to paying subscribers created an unacceptable risk of deception to users, thus violating Article 25(1) of the DSA;

- Whether or not X provided a repository of advertisements on the platform via a “searchable and reliable tool” allowing “multicriteria inquiries and through application programming interfaces,” as required by Article 39 of the DSA;

- Whether or not X met its obligations to provide qualified researchers access to requested platform data for approved purposes under Article 40(12) of the DSA.

For each of these violations, the Commission lays out its preliminary findings regarding each potential violation, arguments made by X in its own defense, and the Commission's assessment of those arguments. At the end of the decision, the Commission also determines the gravity of these violations—a factor in the fine’s ultimate size. From the document, it is clear that this decision took many months to reach, with extensive back-and-forth between the two parties and additional research by the Commission to ascertain the nature and seriousness of potential violations of the DSA.

For its part, the House Judiciary GOP examines each of these substantive areas in turn before alleging that the Commission decision is pretext for an eventual ban against X. It also repeats certain procedural complaints by X about the Commission’s investigation, which the Commission lists and responds to in its decision. Below, we focus on unpacking the substantive areas for which X was fined before turning to the issue of a possible ban and other future consequences for X.

Is the new X checkmark misleading?

In 2009, Twitter launched “Verified Accounts” after Tony La Russa, the longtime manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, sued the site, alleging that a fake page had defamed him. The program focused on high-profile accounts, whose impersonation could cause the greatest confusion among users. That such confusion was widespread at the time is perhaps best exemplified by Donald Trump’s choice of his Twitter a month earlier: @realDonaldTrump. “Realness” was vital, so that’s what Twitter offered for the most important accounts.

These checkmarks quickly became the ultimate digital status symbol. How Twitter assigned—or, in some tellings, “awarded”—them remained opaque. Conservatives complained about the “‘privileged few’ known as ‘the blue checkmarks’” getting not only special status but also special privileges, such as the ability to limit replies to their posts.

When Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022, he slashed content moderation in the name of “free speech.” This quickly alienated the advertisers who had always provided the bulk of Twitter’s revenue. Musk declared that the platform would rely on subscriptions instead, starting with charging for “verified” status (“Twitter Blue”). Little, if anything, changed in how blue checkmarks were presented to users, but the back end changed completely: now could simply buy “verified” status.

In July 2024, the European Commission issued its preliminary conclusion that this change was deceptive and thus violated Article 25 of the DSA. As the Commission decision notes, “for more than 13 years, users of Twitter could rely on the blue-ribbon badge as a trustworthy indicator that accounts that were vetted by the Verified Accounts program were indeed who they claim to be.”

House Republicans dismiss this claim out of hand, mocking the notional example provided in the Commission’s internal memo, @EcomDonalDuck:

Source: X

It would appear that the Commission picked this as an example that would be relatable without actually relating to any real person—and to avoid politics entirely.

In fact, this would likely be an easy deception case even under US law. X was free to change how blue checkmarks worked, but only if it clearly disclosed that to users. The FTC has said “If the disclosure of information is necessary to prevent an ad from being deceptive, the disclosure has to be clear and conspicuous.” What is true for ads is also true for representations like that made by the word “verified” and design features like the blue checkmark.

Since 2009, Twitter consistently represented to its users that blue checkmarks meant that the user had been “verified.” But after Musk took over, the messaging about checkmarks was anything but consistent, and bound to confuse users. Initially, the company distinguished between checkmarks paid for by monthly subscribers and accounts verified by Twitter, but in April 2023, the site announced that “legacy verified checkmarks” would be removed—with exceptions made for accounts with at least 2500 “verified subscriber followers” (users who themselves paid for the checkmark).

X announced a series of changes via posts on the site. Only in July 2024 did X finally explain all this in a help page. Grok itself admits that X “has never sent a clear, direct notification—such as an in-app alert, email blast, or platform-wide announcement—to all its users explicitly stating that the blue checkmark no longer means the account has been "verified" in the traditional sense (i.e., identity/authenticity confirmation by the platform, as it did pre-2022/early 2023).” X could have avoided any deception claim—certainly in the US and, probably, in the EU—if it had simply offered that kind of announcement.

House Republicans make one final claim about the revised checkmark:

Source: X

This likely refers to a part of the Commission decision noting that “X materially changed the verification process as compared to cross-industry standards, while at the same time maintaining the visual and textual online interface design for ‘verified’ accounts under Twitter’s Verified Accounts program, which was in line with those standards, thereby misappropriating the significance and assurance value of a cross-industry standard for representing accounts whose authenticity and identity has been verified.”

Do researchers have meaningful access to X data?

The House Judiciary Republicans object to the Commission’s decision to fine X for failing to provide required data to qualified researchers on two grounds.

First, the Committee claimed on X that the Commission fined the platform for “not giving enough data to pro-censorship pseudoscientists." This is a spurious and ad-hominem attack; to justify it, House Judiciary Republicans link to a previous thread by Committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-OH) alleging that government agencies worked alongside universities and nonprofit organizations to strongarm tech companies into suppressing conservative speech.

Jordan’s allegations were part of what has been described as an ongoing smear campaign to discredit researchers studying rumors and propaganda during the 2020 election—which culminated in violent insurrection—and the COVID-19 pandemic. That campaign also involved Musk’s release of the Twitter Files, core claims of which have been proven untrue; Musk and Jordan are known to be in close contact on these issues. They also mirror arguments made by the plaintiffs in Murthy v. Missouri, in which the Supreme Court rejected claims of censorship for lack of evidence. Jenin Younes, a lawyer who represented plaintiffs in that case, also worked for the House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, which Jordan chaired.

Second, the House GOP report says that the European Commission violated American sovereignty by “apply[ing] the DSA’s data access requirements extraterritorially,” fining X “for giving data access only to EU researchers and refusing to hand over data about American content.” A close reading of the Commission decision reveals this to be sloppy reasoning.

The DSA does require very large online platforms (VLOPs) like X to provide data to “qualified researchers”; however, the DSA is explicit that the data must be related to “systemic risks” within the European Union (both of these terms are defined within the DSA itself). In theory, American data could fall under this provision, but this is not the given rationale for the fine; rather, the fine was imposed because American researchers requested research on data related to systemic risks within the EU but were rejected by X. To substantiate its assertion, the House GOP report cites page 133 of the Commission decision, where text has been redacted. It reads:

Source: EU decision on X

While the unredacted text would be useful for definitively arbitrating this question, it is something of a minor point because the DSA differentiates requests for public data—things visible to any user on a site—from other types of data. Complaining that the scraping of Americans’ publicly visible social media posts is a violation of US sovereignty is like putting up a billboard and getting angry when people see it. In fact, X will readily sell this same data to paying customers—a point raised in the Commission’s decision. X and the House GOP’s objections seem only to apply to researchers scrutinizing the company.

The Commission spends dozens of pages outlining X’s efforts to stymie research access to data, such as unaffordable fees, overly burdensome applications, nonresponsive communication, and rejections not permissible by law. It considers this a serious violation, because researcher access to data is meant to provide transparency, scrutiny, and accountability to companies large enough to pose “systemic risks” to public safety and political processes within the EU.

Is X’s ad repository up to code?

The House Judiciary Committee Republicans also criticize the Commission’s decision to fine X for “bosu violations related to its ad repository,” an interface used to search for advertisements run on the platform. They argue that the Commission found X’s ad observatory insufficient on minor technicalities: specifically for “producing data in a spreadsheet, rather than directly within X’s website,” and that it did not allow users to apply enough search criteria.

The first claim—that X was fined for providing data only via a downloadable spreadsheet—is oversimplified to the point of apparent dishonesty. The Commission provides painstaking detail on X’s ad repository, which allowed researchers to download a .csv file after they had specified the advertiser’s username, the EU member state in which an ad appeared, and the date range during which it ran on X.

X appears to have made these files intentionally difficult to access and use. To begin with, each file could take several minutes to download—much longer than peer services which provided the file in seconds. The files were also artificially inflated to such sizes that third-party software could not open them; for example, each entry might be repeated as many as 57 times in order to inflate the size of a file to several gigabytes. Such restrictions made the ad repository essentially useless: collecting a full set of relevant data might take dozens of cumbersome searches or, in some cases, prove outright impossible.

The House Judiciary Republicans’ second claim refers to X’s decision to require certain parameters for a search while disallowing others. For instance, a user would have to know the username of the account which ran an ad in advance in order to find that ad, and because usernames were a required field for searches, there is no way to see all ads on a given issue from multiple accounts, or in multiple member states. The DSA provides specific parameters by which ad repositories must be searchable and stipulates that they must be searchable by multiple of these parameters. It does so in order to ensure the repository enables meaningful external scrutiny. X’s repository did not.

Is the Commission decision a pretext to ban X?

The House Judiciary GOP argues that the Commission’s decision is a mere pretext to force X to comply with its demands or face a ban. On X, it went farther, condemning the Commission’s recently announced inquiry into Grok for its industrial-scale generation of nonconsensual intimate imagery of women and girls. The eagerness to defend Grok after it allowed users to create millions of nonconsensual, sexualized, sometimes quite explicit images of women and children while its owner watched and laughed is disturbing. As one of us has argued elsewhere, it suggests that the GOP’s crusade has less to do with defending free speech than preventing accountability—whether legal (for content unprotected by the First Amendment) or ethical (for other content). Or, as the mother of one of Musk’s children said after she was digitally undressed: “You can’t possibly hold both positions, that Twitter is the public square, but also if you don’t want to get raped by the chatbot, you need to log off.”

Because the EU decision is now public, readers can decide for themselves if the Commission’s requirements are unreasonable. The Commission gave X ninety days to reform its blue checkmark program and file action plans for improving its ad repository and process for providing requested data to qualified researchers. If X fails to satisfy these requirements, the Commission may level additional penalties or begin the process of banning X from operating in EU member states. The decision to ban X would be a last resort, the consequence of continued noncompliance after months of due process, and would likely be judged before European courts. The lesson here is that other countries have laws and will enforce them, even against the world’s richest man.

The transatlantic confrontation over X’s noncompliance with European law has flared up before, but is growing white-hot after news of a French raid on X’s Paris office and a new UK investigation into Grok, both related to the creation of millions of pieces of non-consensual intimate imagery, including sexualized depictions of children. A Judiciary committee hearing currently scheduled for February 4 promises to be dramatic viewing.

Authors