How Musk's Twitter is Jeopardizing War Crimes Investigations

Raquel Vazquez Llorente / Jul 11, 2023Raquel Vazquez Llorente is the Head of Law and Policy -- Technology Threats and Opportunities at WITNESS.

Since Elon Musk acquired Twitter in October 2022, the platform has undergone numerous policy changes. Once one of the most accessible platforms for external researchers seeking data to investigate human rights abuses, war crimes, and other international law violations, Twitter’s erratic policymaking under Musk may now hamper investigations into international crimes. Crucially, the new policy decisions may also have serious unintended consequences for communities often targeted by governments, such as activists, journalists, and human rights defenders reporting from crises and armed conflicts.

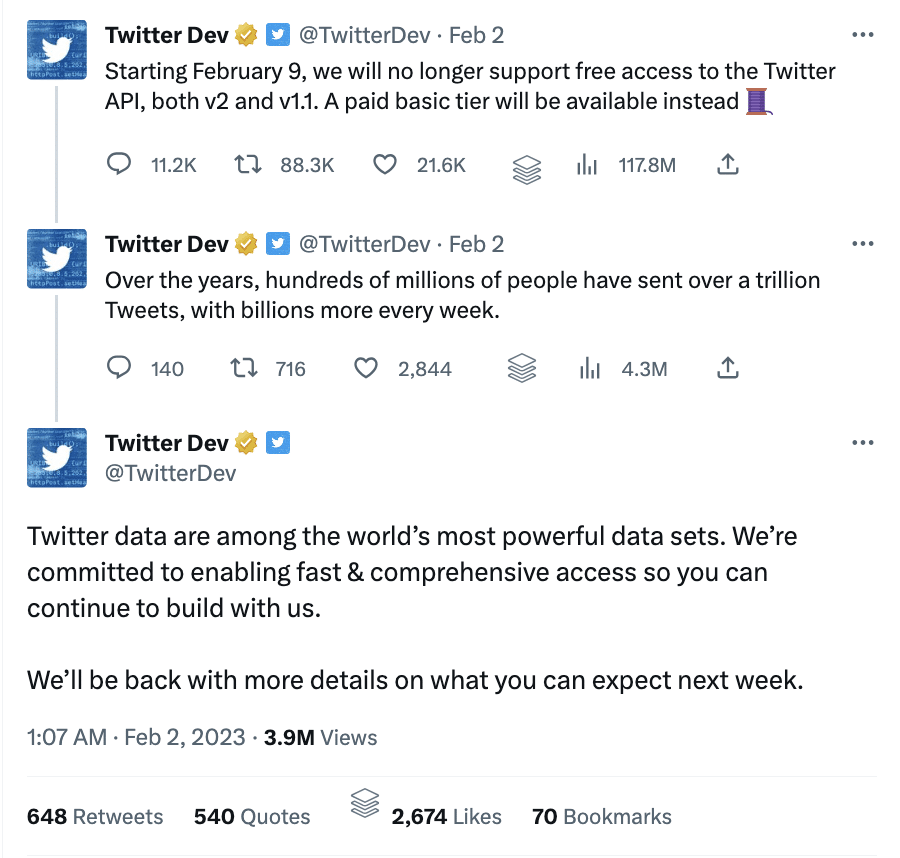

On July 1, in a policy spat spanning five hours over Twitter, Musk imposed restrictions on usage to limit data scraping to train AI models like ChatGPT. The day before, Twitter blocked unregistered users from freely navigating the site, forcing people to create an account–a move Facebook took several years ago. On March 29, after many delays and uncertainties, the company announced new pricing tiers for access to its API, an application that allows software developers to engage with and use Twitter's data directly. Despite global demands from a wide array of actors, including the organization I work for, WITNESS, and at least 113 others, the company effectively shut down free access to data via their API. And last December, Twitter declared that it would remove any tweets or accounts that share someone’s live location, including travel updates, without the permission of the person concerned. Musk had previously given assurances that his “commitment to free speech extends even to not banning the account following my plane.” This policy update seemingly was motivated by Musk’s personal interests, to avoid having his private jet tracked on his platform, and after his son had an incident with a stalker.

The ban on sharing live location: unintended consequences for human rights documentation

While none of these policies are specifically aimed at researchers and investigators using Twitter to gather potential evidence of war crimes and human rights abuses, they are making this work more difficult. For instance, while the private information policy specifies that sharing information that is publicly available elsewhere is still permitted, it carves out an exception for live location. The application of this policy seems inconsistent at best, and selective at worst. Accounts that tracked the flights of Russian oligarchs were suspended. However, multiple accounts posting real-time flight data of dictators and suspected war criminals are still available. And tweets about jet movements related to Russian President Vladimir Putin and Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin were not banned during the recent crisis–but some seem to have been removed over the past week.

Live flight data is important because under universal jurisdiction laws, many countries can only open an investigation when a suspect is present in their territory. Organizations bringing forward litigation on behalf of victims, or investigating international crimes, use this information to file complaints in a timely manner or alert authorities. Twitter accounts sharing flight routes draw this information from unencrypted data that is publicly available on sites like ADS-B, Exchange, and flightradar24. In effect, this Twitter policy seems to have little impact on researchers and investigators beyond making the site a less reliable repository of open-source data.

However, this change can have deeper repercussions for those documenting human rights abuses. In situations of widespread violence or civil unrest, governments may use the new policy to request the suspension of accounts sharing damning footage, as livestream video would reveal the location of anybody featured in it. Twitter says it factors in the intent of the person sharing the information, and there seems to be an exemption for crises to assist with humanitarian efforts. But there is no explicit mention to content with live location when it may be uploaded to raise awareness of human rights abuses. Journalists and activists may still post videos, but to avoid running afoul of the policy, they would presumably have to wait for an unspecified amount of time before posting–as Twitter considers live data to be “real-time and/or same-day information where there is potential that the individual could still be at the named location.”

Complicating the takedown evaluations is the loss of experts who previously provided this guidance. Less than two months into Musk’s reign, Twitter disbanded its Trust and Safety Council, an advisory group consisting of independent researchers and human rights activists from around the world (of which WITNESS was a part). Musk also laid off the human rights team and countless other professionals focused on trust and safety. These teams were essential to ensure that the company resisted takedown demands and data requests from governments that do not comply with human rights standards. Twitter had even previously filed at least one lawsuit against these orders. Given that the platform reported last year a record-breaking number of accounts specified for content removal, it is critical that their transparency report, due later in 2023, provides quantitative and qualitative analysis of how many of these requests have been actioned under Twitter’s private information and media policy, specifically for live location data.

Twitter Blue: How it affects human rights defenders and war crimes investigators

Similarly worrying for activists and human rights defenders is Twitter’s new verification regime, which requires a phone number and algorithmically disadvantages those who cannot afford the fees or do not want to buy the service. Requiring phone numbers for verifying accounts means that the use of this data will be at the whims of the company–for instance, to drive advertising and revenue, a priority for Musk–or worse, available to those who want to target human rights defenders. This fear is not unwarranted considering that under Musk’s tenure the company had seen a dramatic spike in government requests to either remove content or reveal information about a user–with the platform fully complying with 83 percent of these requests (In 2021, before Musk's acquisition, the figure was around 50 percent). This data is submitted by Twitter voluntarily to the Lumen database. Following reporting of these figures by several outlets, the company stopped submitting copies of the notices.

Especially in authoritarian countries, Twitter’s traditional blue check was a useful sign for journalists and activists to denote that an account was verified as authentic. Aside from risking malicious access to phone numbers, the new paid system will disproportionately affect those who are recording footage that may be probative of international crimes and other abuses. It will also make it harder for researchers and investigators to find this content, as accounts that pay for verification will be prioritized in ranking and search results. Additionally, the platform just announced in July that Tweetdeck, a free dashboard popular among open source investigators, will only be accessible for verified users–further complicating discovery. These policies and Twitter’s complacency with surveillance and censorship laws may have a chilling effect on human rights defenders, who may become disinclined to share their content on the platform.

Access to data and the European Digital Services Act: an opportunity to advance justice and accountability

Journalists and activists take great risks to document international crimes and human rights abuses. Twitter used to be seen as a company that largely kept these voices public and allowed researchers to use their API freely to collect critical human rights content for further investigations. More importantly, changes that limit researchers’ access to data, such as shutting down free access to the API, raise alarms about how the company complies with relevant and recent legislation in the European Union, notably the Digital Services Act (DSA).

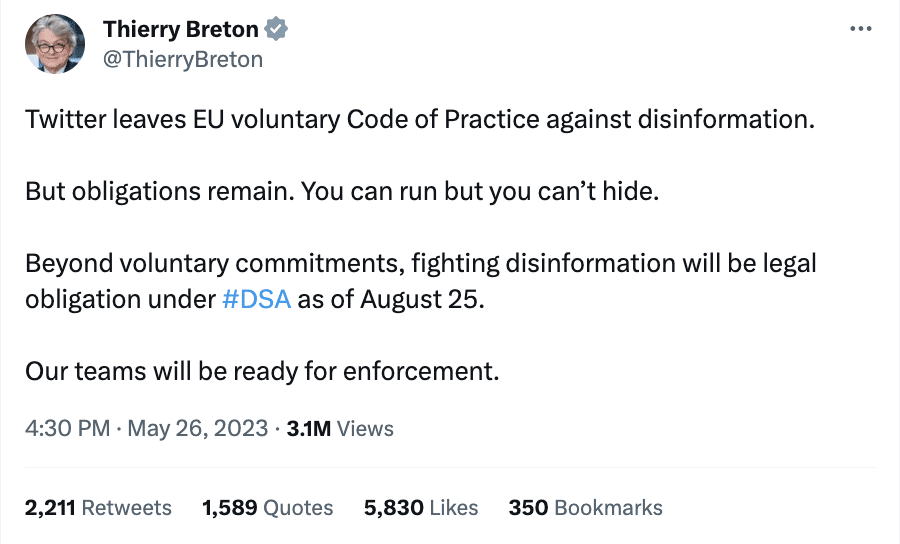

This law imposes obligations on platforms to tackle illegal content and societal risks online, and includes additional rules for platforms like Twitter that have at least 45 million monthly active users. These very large online platforms–or VLOPs–will have to comply with the DSA starting August 25. The new accountability regime works in tandem with the voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation, which Twitter withdrew from in late May, prompting the reaction from the EU that “obligations remain” and that “teams will be ready for enforcement.” After this and other previous warnings, the platform finally met with European Commissioner Thierry Breton in June.

The DSA is important for justice and accountability for international crimes because under Article 40, researchers can access platform data given certain circumstances. WITNESS recently submitted an opinion to the European Commission, outlining how this provision on researcher’s access to data can positively impact justice and accountability for international crimes. For instance, platform data can help investigators collect information on propaganda and other harmful speech in situations of human rights crisis and armed conflict, or analyze online recruitment of official or irregular forces that may become implicated in later crimes and abuses. Moreover, the DSA can also help researchers study how narratives around violence spread in war and similar contexts, and how the mobilization of resources to perpetrate violence against people unfolds on Twitter.

The DSA will bring increased transparency around how Twitter uses automated systems to identify and remove content that violates a company’s policies. These insights can be invaluable for researchers and investigators who want to help platforms design identifiers and processes to collect relevant posts. This is a necessary first step to preserve content that can facilitate our understanding and the adjudication of international crimes and other widespread human rights abuses.

It is yet unclear how API restrictions may affect DSA compliance as the legislation does not specify how researchers should gain access to platform data. This said, failure to commit to voluntary codes that mitigate risks, like the Code of Practice on Disinformation, can be interpreted as a sign of non-compliance. Breaches of the DSA can bring penalties of up to 6 percent of global annual turnover and repeated non-compliance can lead to Twitter losing access to the EU.

Musk’s policies are turning Twitter less transparent, making human rights documentation more difficult, and putting the platform in conflict with the EU. While the company is unlikely to bend to public pledges to protect human rights defenders or war crimes documentation, the EU may hold the keys to rekindle Twitter as a platform that can be leveraged to advance justice and accountability for international crimes.

Authors