Free Speech Advocates Express Concerns As TAKE IT DOWN Act Passes US Senate

Kaylee Williams / Feb 21, 2025

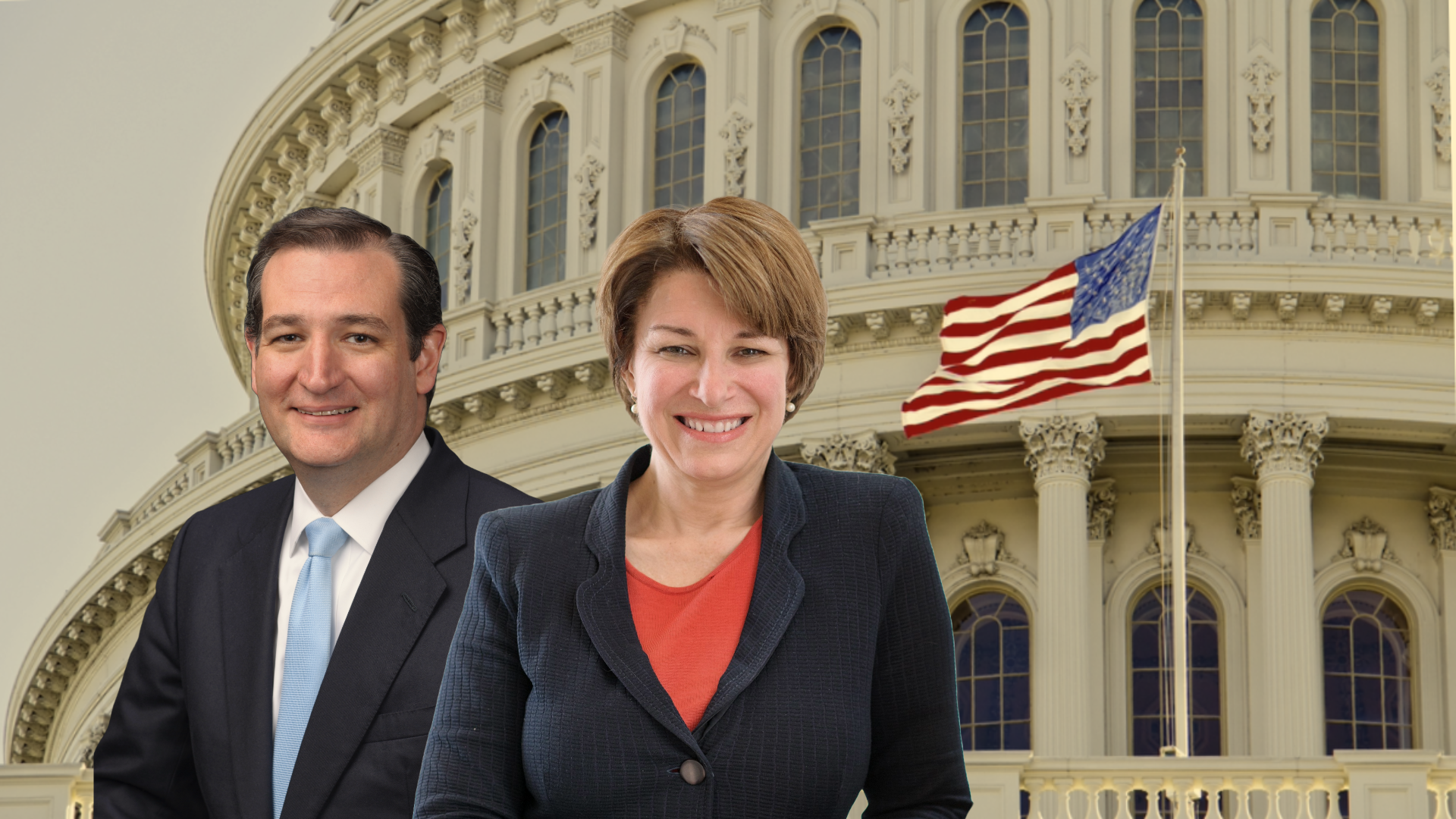

Composite. Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN).

On Thursday, Feb. 13, a bill criminalizing the publication of non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII)—including sexually explicit deepfakes—unanimously passed the US Senate. Although the vote has been lauded by several organizations advocating for victims of sexual exploitation, digital rights and civil liberties organizations have argued that the bill’s takedown requirements may present First Amendment conflicts and lead to undue censorship of lawful speech, including legitimate pornography.

Co-sponsored by Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), the “Tools to Address Known Exploitation by Immobilizing Technological Deepfakes on Websites and Networks Act,” or TAKE IT DOWN Act, makes it illegal for a person to “knowingly publish” any non-consensual “intimate visual depiction” with the intent to “abuse, humiliate, harass, or degrade” the subject. This includes AI-generated content featuring “identifiable” individuals.

However, unlike other deepfake bills previously introduced in Congress (see the SHIELD and DEFIANCE acts), TAKE IT DOWN proposes a notice and takedown (NTD) mechanism that requires social media platforms, websites, direct messaging systems, and any other digital forums where non-consensual content could be shared to “(A) remove the intimate visual depiction; and (B) make reasonable efforts to identify and remove any known identical copies of such depiction” within 48 hours of first being notified about it, either by the subject or someone acting on their behalf.

And while several organizations have praised the bill’s progress as a much-needed step in the effort to achieve nationwide protection against image-based sexual abuse (IBSA), others have suggested that the bill may lead to more harm than good.

Concerns about Constitutionality

In a letter to the Senate, the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) and a group of cosignatories including the Freedom of the Press Foundation, New America’s Open Technology Institute, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) argue that the TAKE IT DOWN Act “is likely unconstitutional and will undoubtedly have a censorious impact on users’ free expression” due to its failure to carve out exceptions for commercial pornography and “matters of public concern” in its NTD mechanism. The letter argues that attempts to comply with the law could “result in the takedown of consensual, constitutionally protected speech.” Furthermore, the letter argues that the bill’s 48-hour window for takedowns “heavily incentivizes” the use of potentially invasive, unreliable, and overzealous automated detection techniques to weed out illegal content at scale.

Joe Mullin, a senior policy analyst at the EFF, wrote on Feb. 11 that if passed, TAKE IT DOWN would create “a far broader internet censorship regime” than the current provisions outlined in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which Mullin says has been “widely abused to censor legitimate speech.” “But at least the DMCA has an anti-abuse provision and protects services from copyright claims should they comply,” Mullin notes. “TAKE IT DOWN contains none of those minimal speech protections and essentially greenlights misuse of its takedown regime.”

Fears over ulterior motives

Tech policy experts have debated the First Amendment implications of anti-deepfake legislation for years, but concerns about regulatory overreach have grown even more urgent since the 2024 election when conservatives won control of every branch of the US government. The Trump administration has demonstrated a willingness to restrict speech that does not align with its stated values, as evidenced by the crippling of USAID and foreign aid funding under the guise of rooting out DEI programs and the executive order suppressing political speech on college campuses as a means of combating antisemitism.

This raises concerns that laws intended to combat deepfake abuse could be co-opted to justify broader censorship of legally protected speech deemed “obscene,” “indecent,” or taboo by far-right conservatives, such as adult content, sexual education materials, and information about LGBTQ+ rights and history. The Republican’s interest in censorship of this kind was outlined in Project 2025—the unofficial GOP policy wishlist published by the Heritage Foundation in 2023—and undergirds a recent “explosion” in new laws restricting access to pornography across roughly a dozen (predominantly conservative) US states, including Cruz’s home state of Texas.

Efforts to prohibit the spread of pornography and other sexually explicit content have been a staple of conservative politics for decades. Similarly, anti-pornography activists have always argued that sexual content presents an inherent danger to children, a fact which is often shoe-horned into modern attempts to curb the publication of information related to sexual health, reproductive rights, and other marginally relevant yet politically salient topics.

The anti-pornography movement has also historically conflated abusive content—which was created or distributed without the consent of the subject(s)—with that of pornography writ large when there is, in fact, a significant legal and ethical distinction. In the US, legitimate pornography (in which all depicted individuals are consenting adults who willingly participated in its creation) is a legally protected form of speech, while NCII is not.

Some of this confusion is likely due to semantics, as misleading terms like “revenge porn” and “deepfake porn” tend to be those most frequently used by the press and other public figures referring to various forms of NCII. For years, feminist writers and legal scholars have advocated for the adoption of terms like “image-based sexual abuse,” which better emphasize the difference between content created consensually versus non-consensually. Law professors Clare McGlynn and Erika Rackley wrote in 2016, for example, that “The labeling of image-based sexual abuse as ‘porn’ implies a consent and legitimacy which is not warranted, as well as leading some policy-makers down the wrong path by thinking that images must pass a threshold of ‘porn’ or ‘obscenity’ before being unlawful; or that the perpetrator must be acting for purposes of sexual gratification to be criminalized.”

Senator Cruz’s public messaging surrounding the TAKE IT DOWN Act demonstrates several of these tactics historically used by those looking to prohibit pornography or censor other forms of legal speech. While the bill criminalizes non-consensual depictions of both adults and minors, Cruz’s website leans into the bill’s potential to mitigate the sexual exploitation of young people specifically, calling TAKE IT DOWN a “bill to protect teenagers from deepfake ‘revenge porn.’”

This messaging plays into valid public concern for children's safety while obfuscating that if passed, the bill may require platforms to encroach on protected speech to meet its NTD requirements.

Broad support for the bill’s intent

Many organizations advocating for victims of sexual exploitation have praised the bill’s Senate passage. The National Center on Sexual Exploitation called the bill a “beacon of hope” and “a major step forward” in combatting image-based sexual abuse, while the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children wrote on Facebook that it looks forward to “continuing our work with the bill’s Senate sponsors…to ensure this important bill becomes law.”

A list of 102 supporters of the bill was also published by Senator Cruz’s office. In addition to victim advocacy groups, the list also includes the SAG-AFTRA union, a number of anti-pornography groups (the National Decency Coalition, Porn Free Colorado, etc.), anti-human trafficking organizations (Nurses United Against Human Trafficking, Yellowstone Human Trafficking Task Force, etc.), police associations (National Association of Chiefs of Police, National Association of Police Organizations, National Sheriff’s Association, etc.), dating app developers (Match Group and Bumble), and a variety of prominent tech companies (Microsoft, Meta, TikTok, Google, Snap, etc.).

Time for a fix?

The CDT letter urges Congress to modify TAKE IT DOWN in an effort to better protect free expression, in part by adding language that would limit the scope of the NTD mechanism to public posts (rather than private or encrypted channels) and carve out the necessary exceptions for commercial pornography and other forms of legitimate speech. However, it remains unclear whether any House representatives plan to propose the amendments that would be necessary to achieve these goals. On January 22, Rep. María Elvira Salazar (R-FL) re-introduced a House version of the bill—alongside Reps. Madeleine Dean (D-PA), Vern Buchanan (R-FL), Debbie Dingell (D-MI), August Pfluger (R-TX), and Stacey Plaskett (D-VI)—which featured the same issues, suggesting that they are not likely to push for the changes.

Other representatives, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), have publicly supported other, less restrictive bills that seek to criminalize the sharing of NCII while preserving free speech and privacy rights, including the DEFIANCE Act of 2024. Similarly, the SHIELD Act, which is currently awaiting a Senate vote, “establishes federal criminal liability for people who distribute others’ private or explicit images online, or threaten to do so, without consent,” and was reintroduced by Senators Klobuchar and John Cornyn (R-TX) just one day before TAKE IT DOWN was passed in the Senate. Notably, the SHIELD Act was first introduced in 2019 and written in alignment with model legislation developed by the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative.

The existence of alternative bills that protect NCII victims without also implicitly restricting legitimate speech suggests that lawmakers can craft legislation that imposes reasonable criminal penalties for IBSA perpetrators and safeguards the speech and privacy rights of all Americans.

This balance is crucial, as overly broad measures could risk undermining fundamental rights and triggering litigation. As EFF’s Joe Mullin wrote in his critique of TAKE IT DOWN, “While protecting victims of these heinous privacy invasions is a legitimate goal, good intentions alone are not enough to make good policy.”

Authors