Elon Musk Will Test the EU’s Digital Services Act

Gabby Miller / Sep 11, 2023Gabby Miller is Staff Writer at Tech Policy Press.

Elon Musk, the self-proclaimed free speech absolutist, has once again ramped up attacks meant to silence his critics, this time while bolstering an online movement with ties to white nationalists and antisemitic propagandists. His latest target is the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an anti-hate organization focused on combating antisemitism, which he threatened with legal action via Tweet early last week. Musk blames ADL for the exodus of advertisers from his rapidly deteriorating social media platform.

At the same time, X (the platform formerly known as Twitter) is now legally compelled to begin its first yearly risk assessment to prove compliance with the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which went into effect for designated Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Search Engines (VLOSEs) like X earlier this month. One of the Act’s goals is to mitigate against the same types of disinformation that Musk continues to amplify across his own platform.

Musk may well be on a collision course with EU regulators newly armed with the assessment and enforcement mechanisms of the DSA. It's as yet unclear how far Musk is willing to go to test the new law, or how punitive EU officials are willing to be should he fail to comply with it. But regulating one of the world’s most influential social media platforms – led by an impulsive billionaire with near unilateral decision-making powers – will likely bring about conflict. Either way, Musk seems prepared for a public showdown with just about anyone, Brussels included.

Musk Targets a Scapegoat

#BanTheADL began trending on X in the wake of a meeting between X CEO Linda Yaccarino and Anti-Defamation League National Director Jonathan Greenblatt, at which Yaccarino sought to learn from Greenblatt what X could do to more “effectively address hate on the platform.” According to a Rolling Stone report, the hashtag was first amplified by Keith Woods, an Irish Youtuber and self-described “raging antisemite”; Matthew Parrot, the co-founder of the neo-Nazi group that organized the deadly “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA; and Andrew Torbas, a Christian nationalist and co-founder of the far-right social media platform Gab, among others.

Along came Musk. The X owner first engaged with #BanTheADL by initially liking Woods’ tweet that falsely alleged the ADL was blackmailing social media companies into removing free speech from their platforms and later replying that the “ADL has tried very hard to strangle X/Twitter,” according to Rolling Stone.

This quickly escalated into Musk scapegoating the ADL for the platform’s precipitous loss of advertising revenue, which he claimed resulted from the ADL’s campaigns pressuring advertisers to leave a platform now rife with hate speech and antisemitism. Last Monday, he tweeted that X has “no choice but to file a defamation lawsuit against the Anti-Defamation League” to clear his “platform's name on the matter of anti-Semitism.”

While it’s unclear whether Musk will follow through with his threats against the ADL, legal action is not out of the realm of possibility. Last month, X filed a lawsuit against the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) that accused the nonprofit of misusing Twitter data for its research that – like the ADL – cost X significant advertising revenue. While some observers dismissed it as a SLAPP suit, others interpreted it as just one part of a more calculated effort by Musk to sue his way out of accountability.

X vs DSA

Meanwhile, all designated VLOPs and VLOSEs were ordered by the EU Commission to comply with the DSA by Sept. 1, meaning platforms with at least 45 million monthly active users were required to submit their first mandatory risk assessments.

X is just one of the seventeen other designated VLOPs that now must demonstrate how they plan to clamp down on disinformation and make it easier to remove illegal content, among other requirements. (Tech Policy Press previously reported that only half of the designated tech companies publicly released summaries of their compliance plans ahead of this deadline.) Meanwhile, researchers and civil society groups are waiting to see what type of actions rise to the level of “systemic risk.”

To begin defining this unknown, the European Commission published a first-of-its-kind report at the end of August that establishes a risk management framework for the DSA. The two-pronged framework, which creates a methodology for risk assessment and risk mitigation under the DSA’s Articles 34 and 35, respectively, establishes a baseline for future audits. However, its findings also illuminate how Musk’s systematic dismantling of X’s trust and safety guardrails contributed to Russia's disinformation campaign during the first year of its illegal war in Ukraine.

The study, conducted by a team of researchers at Reset, found that all major social media platforms enabled the Kremlin to target the European Union and its allies. A particular driver of reach and influence for the Kremlin-backed accounts in the first half of 2023, however, was the dismantling of X’s safety standards. (Disclosure: Tech Policy Press receives funding from Reset.)

According to the report, the average engagement of pro-Kremlin accounts rose by 22 percent across major online platforms, like Facebook and TikTok, between January and May 2023. The increase was largely driven by Twitter though, where engagement grew by 36 percent after Musk axed mitigation measures that once curbed Kremlin-backed accounts. In April, a former X employee told NPR that this decision was deliberate, and Musk “took a chainsaw to the visibility filter rules” that once placed guardrails on authoritarian state propaganda from countries like Russia, China, and Iran. The move was welcomed by Putin’s chief propagandist, Margarita Simonyan, who publicly thanked Musk for de-labeling her account as “public funded media.”

Twitter’s withdrawal from the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation in May 2023, a voluntary Code that platforms joined in 2018 and that was later strengthened in 2022, only further weakened the already insufficient mitigation measures, according to the study. A separate analysis of the baseline self assessments submitted by platforms under the Code – which Twitter filed before backing out – found that “Elon Musk’s Twitter failed every single indicator and gave every impression of blatant non-compliance (e.g., by self-plagiarizing much of their report from previously published boilerplate text).”

The increase in the prevalence of disinformation and hate that Musk not only allowed on the platform but contributed to himself may have violated the DSA had it gone into effect last year. But given that parts of the law are now officially in effect, and the first audits due next year will include platform activity from August 2023 onward, it’s not immediately clear what options the EU has to compel Musk into compliance without first reading the fine print.

Possible Consequences Under the DSA

So what might be the process to rein in an uncooperative Very Large Online Platform or Search Engine? Tech Policy Press asked experts for their assessments on potential enforcement of the DSA, ranging from near-term noncompliance penalties to the most extreme case scenarios, including a temporary suspension of the platform in Europe. We also asked what the likelihood of each step coming to bear is, and what the political consequences might look like if they do.

If you can cut through the DSA’s dense legal language, the procedural steps for enforcement are well-defined:

1) If a Very Large Online Platform (VLOP) or Search Engine (VLOSE) is found in violation of the DSA, the European Commission would have to notify the company of the infringement (i.e. illegal content) and then provide a “reasonable period” for the company to remedy it. What constitutes a reasonable period is left undefined.

2) The noncompliant VLOP or VLOSE must then draw up an action plan for the Commission on how it will address its infringement. If the action plan is insufficient or poorly implemented, the company may face penalties, including fines of up to six percent of its total worldwide annual turnover or periodic penalty payments. The penalties must take into account whether a service systematically or recurrently failed to comply with its DSA obligations. These penalties can be appealed.

3) The Commission can also ask the Member State where the provider is mainly located to get involved. The national regulatory body would, again, ask the platform or search engine to come up with an action plan to address the infringement. If the platform does not cooperate within the time limits provided, the regulator can request its national judicial or administrative authorities to order an intermediary to act on the infringement.

4) As a last resort, noncompliance with a judicial or administrative order could result in a VLOP or VLOSE being temporarily suspended for up to four weeks. It is still, however, possible for a Member States’ Digital Services Coordinator (DSC) to “extend that period for further periods of the same lengths, subject to a maximum number of extensions set by that judicial authority.” These decisions can be appealed to the Court of Justice of the European Union.

To address the challenges involved with effectively supervising VLOPs and VLOSEs across EU Member States, enforcement obligations of the DSA will be shared by both the Commission, which is tasked with most Very Large Platform and Search Engine oversight, and by national competent authorities. Assigning the regulating authority will mostly depend on whether infringements are systemic or individual (as outlined in Clause 125 of the DSA Regulations).

“It is safe to assume that the Commission won’t start any infringement procedure against any company until it has received external audit reports,” Laureline Lemoine, a senior associate for the AWO Agency’s public policy services, told Tech Policy Press in an email. These audits, as outlined by the European Commission’s draft delegated regulation, must be done at least once per year by independent auditing organizations with proven objectivity and should reach a “reasonable measure of assurance” to ensure DSA compliance. These audits aren’t due to the Commission until August 2024.

Involving the European Commission, Member State authorities, and the courts at all levels of the enforcement and appeals process was a strategic attempt to build safeguards into the DSA. It also reduces the risk that the DSA might be used (or appear to be used) merely as a political tool.

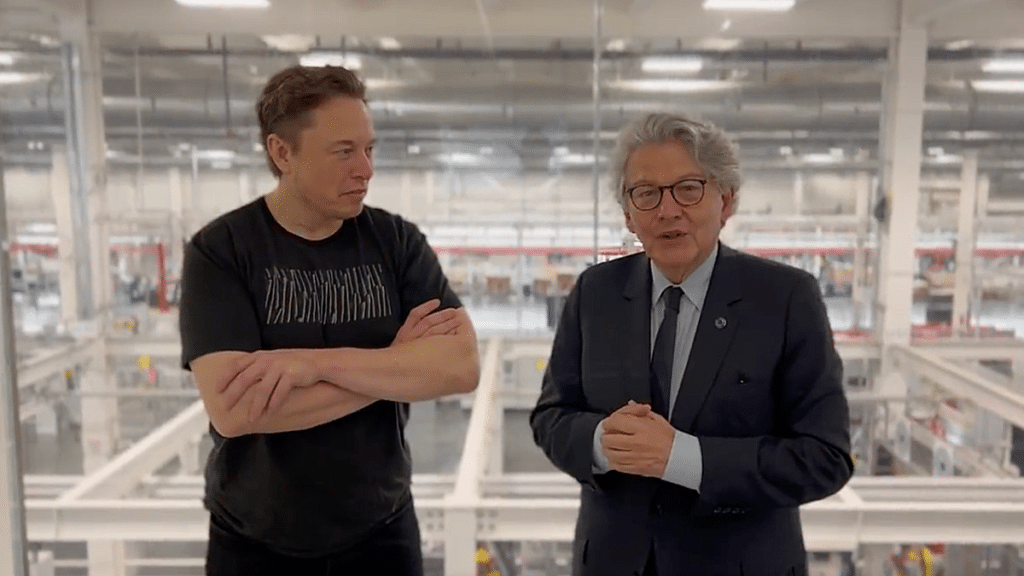

Any of these enforcement steps risks political fallout, though. In May, Thierry Breton, the elected European Commissioner who oversees digital policy, tweeted that Twitter can run but “can’t hide” from its legal obligations under the DSA, appearing to relish the opportunity to take on Musk. Breton’s comments ultimately led X to voluntarily participate in a “stress test” led by the Commission that X allegedly took “very seriously.”

Even if X is uncooperative with the Commission or a Member State’s national regulator, a temporary suspension is highly improbable, according to several experts Tech Policy Press spoke with. Restriction of access to a platform or search engine would have to be determined by a Member State’s judicial authority–Ireland, in X’s case–and can only be done if the infringement “entails a criminal offense involving a threat to the life or safety of persons,” according to AWO’s Lemoine. “The threshold is quite high to reach and seems unlikely,” she explained. “[It] would mean months of procedures and it’s hard to imagine it happening before the end of [this year].”

This multi-layered process is exactly why Dorota Glowacka, an advocacy and litigation expert at the Panoptykon Foundation, believes such extreme measures, however unlikely, could still remain objective. “In principle, because this particular sanction is not imposed solely by the European Commission and ultimately it's the court's decision, I believe it makes this decision kind of independent.”

Ultimately, the DSA must curb harm to EU internet users while balancing their rights to freedom of expression online–a lofty goal that has yet to be achieved at scale by any other regulatory body. Whether the EU can succeed in the face of a clear challenge from the world’s richest man will be a major test of whether democracies can hold the largest and most powerful tech companies to account.

Authors