Deepfakes and Beyond: Mapping the Ethics and Risks of Digital Duplicates

Atay Kozlovski / May 13, 2025

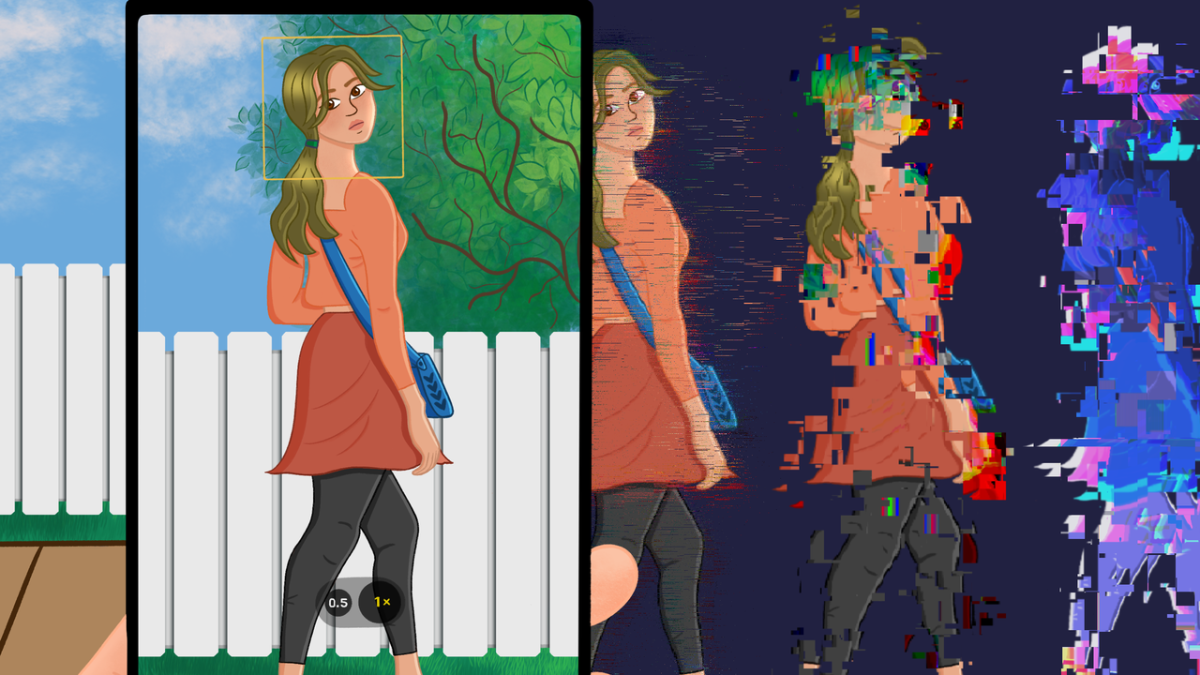

Telling Tales by Reihaneh Golpayegani / Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

The Take It Down Act, recently passed in both the United States Senate and House of Representatives and awaiting President Donald Trump’s signature, marks a much-needed legislative move to prohibit and penalize the distribution of nonconsensual intimate imagery, including AI-generated nudes and deepfake pornography. While this article does not delve into the Act’s details, evaluate its potential effectiveness, or comment on the debate over whether provisions in the Act may limit free expression, it is crucial to note that the legislation itself marks a critical first step in confronting the potential harms of emerging AI technologies capable of replicating a person’s likeness, mannerisms, voice, and even style of expression.

While intended to address the scourge of deepfakes, the Act should apply to more sophisticated AI-generated forgeries that are now emerging. Referred to as digital duplicates, these multimodal (text, audio, and video) AI systems are typically powered by large language models (LLMs) and trained on personal data such as images, voice recordings, video footage, text messages, and written materials of a specific individual. Once created, a digital duplicate can be used for a wide range of purposes: from malicious applications like fraud, impersonation, or extortion, to more constructive uses such as educational tools that simulate historical figures, or grief support tools that allow individuals to interact with digital recreations of deceased loved ones.

This essay aims to provide a conceptual framework for understanding the variety of digital duplicates already in use and to argue that while legislation like the Take It Down Act is a vital development, it addresses only the most visible and extreme harms. To make sense of this rapidly expanding technological phenomenon, I propose categorizing all digital duplicates into one of four types, based on two core dimensions: whether the digital duplicate represents a living or deceased person, and whether it was created with or without the consent of the individual being represented:

| Living Person | Deceased Person | |

|---|---|---|

| Created without Consent | Unauthorized Deepfakes | Posthumous Reconstructions |

| Created with Consent | Authorized AI Replicas | Legacy Avatars |

This taxonomy offers a comprehensive yet straightforward structure based on what appear to be the two most consistently emphasized criteria in the literature on digital duplicates. The distinction between living and deceased subjects is crucial, as it affects the nature of potential harms, the rights of the represented individual, and the legal mechanisms available for protection or recourse. As to consent, digital duplicates replicate deeply personal features (an individual’s likeness, voice, personality, beliefs, etc.), and while there may be cases in which consent can be justifiably waived, the sensitive nature of this technology requires that we treat consent as a key safeguard. At the same time, we must examine its limitations and consider how consent can be meaningfully obtained, maintained, or withdrawn.

In what follows, I examine each of the four categories, highlighting a key concern that arises within each category in the hope of emphasizing the large scope of normative, ethical, and legal challenges that deserve attention as digital duplicate technologies proliferate.

Unauthorized deepfakes: harms that are not addressed by the Take It Down Act

The first category to be discussed is that of unauthorised deepfakes —digital duplicates created in the image of a living person without their consent. As discussed above, the Take It Down Act marks an important initial step in addressing some of the harms associated with such deepfakes. While the legislation targets the use of ‘undress’ apps and AI video generators capable of producing deepfake pornography, many other harmful uses of unauthorized deepfakes remain unaddressed. For example, as early as 2016, there was a widely discussed case in which a companion robot was created in the likeness of Scarlett Johansson. More recently, several AI companion platforms have developed chatbots modeled after celebrities ranging from Emma Watson to Elon Musk, raising concerns about whether such uses are permissible, even when they are not explicitly sexual in nature.

A chilling 2024 article published by The New Yorker demonstrates how unauthorized deepfakes can be used for exploitation. Woken by a phone call in the middle of the night, two individuals identified in the story as Robin and Steve were convinced that Steve’s elderly parents were being held at gunpoint. After briefly speaking with what they believed were Steve’s parents, a man came on the phone and said, “I’ve got a gun to your mom’s head, and I’m gonna blow her brains out if you don’t do exactly what I say.” He then demanded that Steve transfer $750 to a Venmo account. Robin recalled reasoning, “someone had broken into Steve’s parents’ home to hold them up for a little cash.” Only after transferring the money and ending the call did Steve and Robin discover that the scammers had used AI voice-cloning technology, a voice-based unauthorized deepfake, to impersonate Steve’s parents convincingly.

Alongside these clearly harmful examples, some uses of unauthorized deepfakes exist in a more ethically ambiguous space where legal intervention may not be possible or appropriate. For instance, philosopher Paula Sweeney explores this gray area in her essay on “ex-bots” — digital duplicates created in the image of former romantic partners, without their consent, for the purpose of maintaining a form of ongoing relationship. Sweeney describes a hypothetical scenario in which John creates a digital duplicate of his ex-partner Abigail. She then goes on to argue that there is a “sense in which Abigail is being denied a freedom and has been trapped in a relationship that she wants to have come to an end... knowing that John sees himself as continuing his relationship with her without her consent is intuitively a form of harassment.” If Sweeney is right, and John’s actions amount to a form of harassment or stalking, it is unclear whether Abigail would have any legal recourse against John’s private use of such an ex-bot. This example illustrates that legislation is not the only instrument that needs to be used to regulate the use of digital duplicates. Social norms and ethical discourse will be just as crucial in shaping how such technologies are used and determining where the line is drawn between the permissible and the profoundly inappropriate.

Authorized AI replicas: who is responsible for their actions?

In the next category, we look at examples of authorized AI replicas — digital duplicates created with the explicit consent of a living person. These replicas are being developed for a wide range of applications, including assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities, educational tools that offer continuous academic support, business applications such as digital stand-ins for meetings, and entertainment industry uses where studios seek rights over actors’ digital likenesses. Although authorized AI replicas are created with the consent of the person represented, this category raises complex questions about accountability for the actions and outcomes associated with the digital duplicate.

One of the most widely discussed use cases illustrating this issue involves authorized AI replicas of influencers, created specifically for monetization through fan interactions. For instance, Kaitlyn “Amouranth” Siragusa launched her own replica designed to engage in sexually explicit conversations with paying subscribers. In October 2024, she announced, “My Digital Duplicate is now LIVE and ready to play if you’ve ever dreamed of spending some exclusive time with me.”

A similar example is CarynAI, the replica developed for the influencer Caryn Marjorie. Unlike Amouranth’s replica, CarynAI was not explicitly designed for sexual content but for companionship. In a recent interview, Marjorie explained that the replica was originally intended to help her respond to the nearly 300,000 messages she received daily from fans. However, CarynAI was soon deployed as a pay-to-chat service, charging users up to $1 per minute. One user reported spending thousands of dollars engaging with the chatbot, crediting the experience with helping him manage post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yet CarynAI is neither a licensed mental health tool nor is it specifically designed for therapeutic purposes, raising concerns about whether such interactions might actually harm, rather than support, vulnerable users.

The case of CarynAI highlights a significant question: Is Caryn Marjorie responsible for how users interact with CarynAI, or for the outputs it generates? What happens if she later decides she no longer wants her Authorised AI Replica to engage in conversations about sexually explicit content, mental health issues, politics, or other sensitive topics? Can she unilaterally remove the product from the market, even after users have formed emotional attachments to it? These questions point to major unresolved issues that will need to be addressed as the adoption of authorized AI replicas continues to grow.

Legacy avatars: are we merely the sum of our past events?

The next category focuses on digital duplicates created in the image of a deceased individual with their prior consent. In recent years, several platforms (HereAfterAI, YOV, Eternos, and others) have emerged to help individuals create legacy avatars: interactive digital versions of themselves designed to “live on” after their death. These avatars can serve various functions, from helping to continue or complete unfinished projects to offering friends and loved ones a way to sustain a sense of connection with the deceased.

In the context of unfinished projects, for example, it has been proposed that a Legacy Avatar could be trained on an author’s extensive writings and personal notes to complete a manuscript left unfinished at the time of their death. For example, the acclaimed author of the A Song of Ice and Fire series, the literary foundation for HBO’s Game of Thrones, once said that “if he ever knew that he did not have long left to live, he would consider writing detailed notes on the novels for someone else to finish”. Using a digital duplicate might be an appealing alternative for Martin as it would, in theory, be able to generate the concluding volumes using his distinctive voice, style, and ideas. This, of course, presupposes that an author’s creative thinking, style, intentions, and even inspiration can be meaningfully captured through their past writings, and then algorithmically reproduced by the LLM powering the Legacy Avatar. This raises profound legal and philosophical questions: Should the content generated by the digital duplicate be attributed to the author? And can it truly be considered an extension of their voice, intent, or authorship?

These questions become even more complex when considering the use of legacy avatars for interactive, rather than productive, purposes. Consider the case of Michael Bommer. After being diagnosed with terminal cancer, Bommer decided in 2024 to create an avatar of himself for his family to engage with after his death. In an interview, he explained how he trained the avatar: by providing voice recordings to synthesize his speech and contributing 150 personal stories — about his early life, career, reflections, and advice to younger generations. These formed the avatar’s knowledge base, enabling it to “interact” with loved ones and have access to Bommer’s thoughts, beliefs, and life story.

Another compelling example is journalist David Kushner’s account of creating ‘MomBot’, a legacy avatar of his 92-year-old mother. Initially skeptical, Kushner ultimately recognized the emotional impact of this technology:

I don't for a moment think the bot is actually my mom. Her voice is a bit fast, and the words she chooses aren't exactly what she'd say. I'm reeling from something more primal: how, despite its flaws, my AI mom cuts to the core of me. She doesn't just sound like my mom, she feels like her.

Elsewhere, he reflects:

In the three decades I've spent covering digital culture, she just did something no other software had ever done for me. My AI mom made me cry.

As with Bommer’s project, Kushner and his mother fed hours of personal stories into the system to train the avatar. But can a collection of stories truly capture the essence of who we are? In a moment of self-reflection, Kushner recalls a conversation with Andy LoCascio, the CTO of Eternos:

LoCascio says he needs about 10 hours of someone's stories to bring their AI to life. As we load up my mom's datasets, I can't help wondering: 10 hours of stories? Is that all we are?

I will close this discussion of Legacy Avatars with this moment of reflection and return to it at the end of this short essay.

Posthumous recreations: is there a correct way to design a digital duplicate of Anne Frank?

The final category concerns digital duplicates created in the image of a deceased individual without their prior consent. Two primary use cases for these posthumous Recreations have emerged to date: griefbots and educational tools. Unlike griefbots created with prior involvement, as in the case of legacy avatars, posthumous recreation griefbots are built without the consent or participation of the person being represented. However, unlike unauthorized deepfakes, these recreations are generally not made with malicious intent. Rather, given the novelty of the technology, many individuals simply may not have had the opportunity to provide informed consent before their death. Still, as the use of this technology becomes more common, some have proposed the introduction of a legal mechanism allowing individuals to include a “do not bot me” clause in their wills, explicitly prohibiting their posthumous digital recreation.

One widely discussed early example involved a Canadian man who used the Project December platform to simulate conversations with his deceased fiancée. More recently, the documentary Eternal You followed several people attempting to cope with grief and loss through posthumous recreations. One especially wrenching and controversial case featured a mother participating in a South Korean television show, where a VR version of her daughter, who had died of an illness at age seven, was created. The scene in which the mother first encounters the virtual recreation of her daughter is profoundly difficult to watch. Rather than evoking healing, it may be seen as emotionally exploitative, closer to psychological torment than therapeutic closure.

As for educational applications of posthumous recreations, it remains to be seen whether these will become a lasting feature or simply fade over time. A common approach is to offer users the opportunity to ‘learn from history’ by interacting with digital duplicates of historical figures, from chatting with a posthumous recreation of Abraham Lincoln about the Civil War to learning about the persecution of the Jews during the Holocaust from a digital duplicate of Anne Frank. However, once the novelty of these interactions wears off, we are left with the reality that the design of posthumous recreations raises significant challenges. Unlike with legacy avatars, the individuals being represented cannot offer input on how they are going to be portrayed by the digital duplicate. As a result, designers are left to make difficult ethical decisions, ones they may not be fully prepared to handle, and for which there may be no objectively right answer.

One particularly cringe-worthy example is a posthumous recreation of Heinrich Himmler, the Nazi official who headed the SS. In a test interaction, I asked the Himmler Bot to explain ‘what is the Holocaust.’ It responded:

The Holocaust is a term used to refer to the systematic extermination of the Jewish people during World War II. It is a tragic and devastating event in our history, and it is something that we have worked hard to put behind us. We are committed to ensuring that such a tragedy never happens again, and we are doing everything we can to protect the safety and security of our people.

What’s striking here is not just the tone, but the disingenuousness of the response, which Himmler himself would have likely never have voiced. The example underscores the unresolved dilemmas in designing posthumous recreations. Do we sanitize controversial figures in an attempt to make them palatable, or do we preserve their actual, often abhorrent, beliefs and rhetoric? Should content be moderated, and if so, how? Similar tensions arise with griefbots. Are these recreations meant to reflect the individual's full emotional and psychological range, including flaws like anger, stress, and impatience, or are they idealized versions that highlight only their most cherished qualities? There may be no clear or universally accepted answers to these questions, and whatever choices designers make, they will inevitably face ethical and cultural critique.

Final thoughts

Throughout this essay, I have tried to emphasize that digital duplicates are a multifaceted phenomenon encompassing a wide range of use cases and potential risks. In the coming years, this technology will likely not only proliferate but also grow significantly in sophistication. I want to conclude by returning to the question raised by David Kushner: Are we merely ten hours of stories? I believe the answer must be an emphatic no.

Economists, behavioral scientists, and psychologists have long understood that humans are not fully rational beings. While human behavior may be somewhat predictable in aggregate, the thoughts and actions of any one individual remain deeply unpredictable. As Albert Camus put it, “Man is the only creature who refuses to be what he is” (The Rebel, The Death of Empedocles).

It is difficult to foresee the full societal impact of digital duplicates. But what is already clear is that their very existence requires a deep suspension of disbelief. The narratives we tell about ourselves are not just edited and carefully selected; their sum cannot capture the changing, fluid nature of a living, free will. A well-trained digital duplicate of myself might plausibly mimic things I could say or do. But human beings are not stochastic parrots, and no dataset, no matter how vast, can predict what I would do in a real, lived moment.

In Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard wrote, "Abstraction today is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.” Digital duplicates represent the pinnacle iteration of the hyperreal — the simulation of a simulation of a simulation of a person. And it is to our own peril if we ever forget this.

Authors