Canada Needs Independent Researchers to Get AI Policy Right

Renee Black / Dec 3, 2025Renee Black is the CEO of GoodBot.

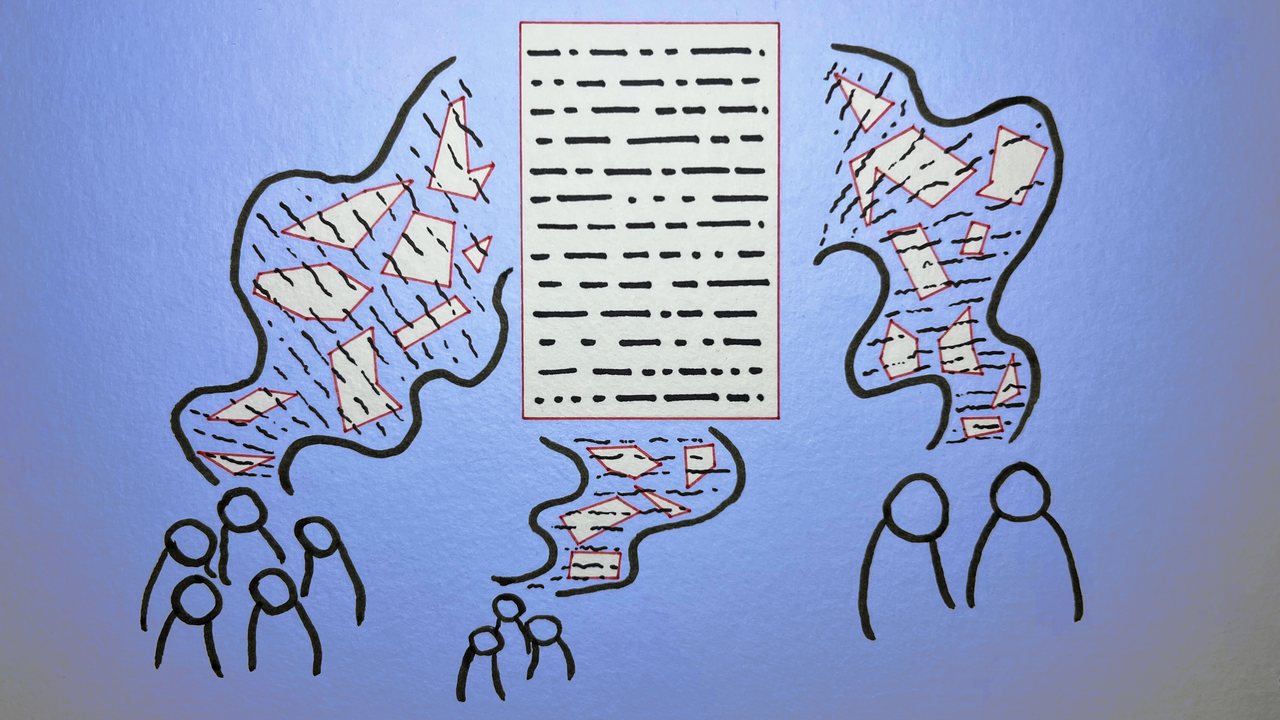

Yasmine Boudiaf & LOTI / Better Images of AI / Data Processing / CC-BY 4.0

As Canada confronts mounting challenges arising from trade threats, prosperity and sovereignty, Prime Minister Carney faces a critical choice in developing AI policy. Yet at a time when public perspectives are urgently needed, the government appears to be prioritizing industry once again while largely excluding independent public-interest researchers in AI policy processes.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Existing risks are amplified by AI and platform-driven disinformation, fragmentation, and inequality. AI policy sits at the intersection of these and many other challenges and has the potential to restore integrity to information ecosystems. Instead of seeing public interest researchers as essential partners in getting AI policy right, the Carney government’s actions suggest that it views them as obstacles.

Captured policy and performative consultations

The private sector has an important role in shaping AI strategy. There are very real issues that inhibit innovations and adoption, while productivity is at a concerning level. Yet, fear and distrust impede adoption. To address these barriers to adoption, participation in policymaking processes must be balanced by independent researchers who are focused on upholding Canadians’ democracy and rights.

The imbalance of voices is evident in the government’s language, investment priorities, and processes that favor industry voices, the appearance of engagement and speed over process integrity. Several factors are of concern.

Most troublingly, many non-industry members of Canada’s AI Task Force receive substantial funding from large AI companies and Silicon Valley foundations. This might not be a problem if the Task Force were otherwise balanced with independent researchers and wasn’t occurring at a time when attacks on independent technology researchers are escalating in deeply concerning ways. But in this context, it exposes a gaping hole in the question of whether AI oversight policy and mechanisms will be independent of the interests of AI companies.

The result is that industry voices appear to be consistently prioritized, while public-interest researchers—experts in privacy, digital rights, Big Tech accountability, and online harms—are systematically sidelined.

What is also puzzling is that Canada’s Minister for Artificial Intelligence and Digital Innovation, Evan Solomon, has repeatedly framed AI around the issue of trust, including at an AI conference in October, where he stated that " technology moves at the speed of innovation, while adoption moves at the speed of trust." However, his actions — such as how the AI Task Force and public submission process were structured — undermine the very trust he needs to build.

Chief among these concerns is that the public submission process is rushed (30-day timeframe to submit with no advanced notice), lacks basic integrity measures (submissions can be anonymous) and that critical concerns are limited (focusing on privacy). Under this process, any AI company could easily generate countless fraudulent submissions to advance industry interests while deceptively representing itself as Canadian consumers. Moreover, limiting the scope of input to privacy ignores a wide range of urgent issues such as the impacts on creator economies, consumer scams and democratic integrity.

Additionally, the Task Force’s industry-skewed composition — along with shared belief among scholars and nonprofits that critical policy decisions have already been made — has led many in civil society to speculate that this process is largely performative. This is not the path to building public trust.

Learning from failure

Both Carney and Solomon have an opportunity to learn from Trudeau’s missteps, under whom attempts at AI and Online Harms legislation failed. While the government eventually found a workable path for Online Harms, both bills were delayed — and ultimately died on the order table — due to rushed processes, structural issues, controversial provisions and a failure to hold genuine consultations, all of which served to undermine public trust. The AI bill (C-27) was especially problematic, with a process that included almost no civil society participation and which proposed to have AI oversight live with Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED), a department whose priority is innovation and economic development, not public safety and trust.

Canada is repeating similar mistakes with recent legislative moves compounding concerns. The Strong Borders Act (C-2) threatens Canadian privacy and sovereignty and poses risks to migrant communities, while relitigating lawful access issues. The Cyber Systems Bill (C-8) ignores urgent gaps in political parties' collection and use of data, including their use of AI in political activities and campaigns. Moreover, the decision to rescind the Digital Services Tax without securing concessions erodes confidence that Carney is defending Canadian sovereignty.

Additionally, the actual or perceived belief that consultations are largely performative suggests the government has not learned from the past. Several open letters — including from digital rights groups and community organizations — highlight key concerns that this process is captured and will do nothing to protect Canadians, especially those disproportionately impacted, from US billionaires profiting from risks of privacy violations, information manipulation and public safety. Canadian legal and policy scholars such as Renee Sieber (on the need for genuine engagement), Mila’s Valerie Pisano (on lessons from regulating other complex sectors) and Teresa Scassa (on process capture) all draw attention to substantive problems with the consultation processes and policy framing discussions.

How independent researchers help

Public interest AI researchers focus on advancing research on how technologies like social media and AI chatbots erode social trust, mental health, and critical thinking, along with the potential and unintended impacts of policy on people and ecosystems. They bring long-term systems thinking perspectives that transcend electoral cycles to policy processes while understanding community needs in ways that industry-centric processes will always miss. They represent constituencies and value systems where anxiety about AI is high, trust is low and where considerable thinking has already gone into imagining technologies grounded in trust, safety and human agency. Moreover, they include voices that can inform strategies needed for creating a roadmap to advancing ethical and beneficial AI development and adoption in Canada.

Public interest researchers don’t need deference, but if the government is truly committed to building trust and policy that balances innovation and adoption with public interest, it is in its own interest to engage on issues where researchers bring legitimate, irreplaceable expertise.

Five essential reforms for consultations

To reset this relationship and strengthen Canada's AI policy development, Canada should rethink its consultation processes and reset its relationship with public interest researchers.

1. Extend consultation timelines

Initial consultation periods must be extended to enable genuine engagement and establish concrete recommendations for continuous consultation processes. Rushed timelines undermine quality input and perpetuate the perception of predetermined outcomes. One of the open letters proposes at least three months.

2. Consultations that are informative, not performative

The government should commit to creating new policy frameworks – or substantially adapting existing drafts – in response to concerns raised by public interest researchers during consultations. Real engagement means involving researchers at the policy development stage—not after decisions are made—and being willing to be challenged in how policy is framed, regardless of where feedback originates.

3. A task force rebalanced with independent voices

The AI Task Force should be revitalized to properly balance independent researchers who can address AI's impacts on Canadians and who have no actual or perceived conflicts of interest. Lack of meaningful representation from independent researchers compromises the Task Force's legitimacy and effectiveness.

4. An online submissions process with integrity and wider scope

Given the over-representation of industry in tech policymaking processes, including via trade conversations, coupled with the sector’s track record of interference in public consultations (not to mention nonprofits established to advance industry interests), the government must take intentional steps to ensure integrity in public consultation processes. This includes taking privacy-respecting validation measures to ensure contributors represent perspectives honestly, even if the content of submissions is submitted anonymously.

To properly balance the diversity of perspectives, including both consensus and differences, submissions should be categorized by type (e.g., private sector, public interest nonprofits, academia, industry association, citizens, etc.) and sector (e.g., tech, banking, consumer advocacy, policy). It is critical to note that there can be legitimate reasons to protect contributor identities—such as whistleblowers, industry insiders, and vulnerable groups that could be targeted by future administrations, as we are currently witnessing in the US—and that a well-designed process can validate contributors while maintaining appropriate privacy. Without integrity checks, consultations risk being even further captured, while providing the deceptive illusion of engagement. Moreover, integrity means not limiting the scope of consultations in ways that will, intentionally or otherwise, skew consultation outcomes.

5. Normalizing deliberative engagement in policymaking

Given the rapid evolution of AI and societal impacts, coupled with declining trust in government institutions, Canada should use this moment to rethink policy engagement processes. Specifically, they should establish or fund ongoing consultation mechanisms in partnership with independent civil society organizations to consult with the public through the use of deliberative approaches and technologies. These mechanisms can identify critical areas of opportunity and risks, including emerging policy blind spots, to help advance fairer digital markets, responsible innovation, productivity and trusted AI adoption.

A choice for leadership

Prime Minister Carney has inherited leadership during a global democratic crisis. Authoritarianism is rising, misinformation is industrialized, and trust in institutions is collapsing. Canada's strength will not come from technocratic management alone but from a renewal of democratic engagement, civil society resilience, and commitment to human rights.

If the government continues on its current adversarial path with researchers, it risks slowing its own policy agenda and is also likely to fail to convince Canadians to trust and adopt AI. Another way forward is to recognize that democratic strength comes from expanding conversation, engaging critics, and distributing expertise rather than controlling and centralizing it.

Thankfully, there is a small bright spot. While Minister Solomon has been advancing his consultation agenda, House and Senate members appear to be taking these concerns seriously at the Committee level. The House is convening a study on the Challenges Posed by AI and its Regulation, while the Senate committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology will examine the impacts of AI in Canada, including data governance, ethics, privacy and safety, and risks, benefits and social impact.

Likewise, the Senate Committee on Transport and Communications has commissioned a report on opportunities and challenges of AI, where it will explore the use of AI in content creation, distribution and processing, implications for Canada’s copyright and intellectual property framework, the rise of AI-generated disinformation and deepfakes, and the impacts of AI on public trust and media integrity. The Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage will also convene a study to examine the impacts on creative industries. In the absence of ministerial leadership, these interventions are most welcome.

Independent public interest researchers will continue their work regardless of how the government proceeds. The question is whether the government will treat them as partners in building Canada's AI future or as obstacles to be managed. What is decided today will shape not just AI policy in the coming years, but also democratic resilience and trust in Canada as it faces unprecedented challenges.

Authors