A New Framework for Understanding Algorithmic Feeds and How to Fix Them

Laura Edelson / Mar 10, 2025There are few things today that unite people like social media. In the US, close to 70% of adults use some kind of social media, and distrust of social media companies is almost as universal. There’s no contradiction here: Instagram, TikTok, and all the rest are simultaneously fun, opaque, useful, capricious, occasionally horrifying, and utterly irreplaceable in our modern society.

As it often goes with technology, the trick is in extracting the benefits of social media while minimizing harm. We want planes that take us places without falling out of the sky (very often), drugs that cure diseases without causing (too many) deadly side effects, and social media that connects us without fueling (too much) mental health harm. But social media platforms and the algorithmic feeds that fuel them pose a unique challenge to advocates who want to make them safer as well as regular users: nearly everything about them (except their final output) is entirely obscured from the public, hidden behind at best quarterly ‘transparency reports’ that are parseable only by experts and the occasional blog post or technical explainer that similarly geared only to specialists and researchers.

So how do we move forward? Clearly, we need more transparent and open frameworks for social media. ActivityPub (the open-source backbone of Mastadon, Threads, and other Fediverse networks) has attempted to do this for the social graph component of social media (the ‘graph’ of users that is constructed from the web of friends and followers). However, as newer platforms like TikTok show, a social graph may not even be a necessary component of modern social media.

Instead, my research suggests that the feed algorithm is the most defining feature of social media. To be sure, these algorithms aren’t the only way users ever see social media content—sometimes, people search for a specific term, or they navigate to content with a link they already have. But, algorithmic feeds appear to control a significant amount of what social media users are shown, and most users have next to no idea how they work. Demystifying algorithmic feeds for users and developing a general framework that could be used to describe any social media feed has been the work of my co-authors and me for the last two years. You can read our work in detail here, but the core concepts we developed are relatively straightforward.

In our full paper, we explore the design of several aspects of algorithmic feeds, but if there is one concept that is key to understanding how these systems work, it is this: Algorithmic feeds are optimized around certain goals, and their outputs are highly dependent on those goals and the design choices algorithm designers make to achieve them. We identified four primary dimensions along which these optimization goals can vary from low to high: Usage Intensity, Specificity, Novelty, and Content Timeliness. These four design parameters all involve hard tradeoffs, and how platform designers choose to make them will be the most important factors driving users’ experience of that social media platform.

- Usage Intensity: Whether the platform optimizes for active engagement (commenting, sharing) or passive consumption (watching, browsing). When people have intense interactions and experiences, whether they are positive or negative, they tend to end them sooner. This is why platforms like YouTube that maximize for time spent watching also tend to recommend more low-intensity content.

- Specificity: Whether content is targeted narrowly to individual interests or broadly to maximize audience size. Very broadly appealing content that many people like also tends to be content that very few people love or feel strongly about.

- Novelty: How much the algorithm introduces unfamiliar content versus reinforcing known preferences. Algorithm designers mostly want to show users content they like. After an initial learning period, they have enough information about how users will react to content to know at least some categories of content that users will engage with or watch for a long time. However, algorithms can also explicitly choose to introduce novel content that they have no way to know how a user will react to. Sometimes, this is part of the appeal of an algorithm—users may like being introduced to new things. It also has benefits to the platform because it is a way of learning new things about a user that they themselves might not even know. But, it is also a risk because users may react negatively to new content that they do not like.

- Content Timeliness: How heavily recent content is prioritized over older material. This one is simple—it simply describes how old, generally speaking, the content being shown to users is. Some types of content are evergreen (art history, for example), while others (news about a breaking event) are only relevant if they are very recent.

Every social media feed algorithm can be classified along each of these four dimensions. We reviewed dozens of documents—including patents, academic papers, leaked design documents, and even company blog posts—to do just this for five major social media platforms: Facebook, TikTok, X, Reddit, and YouTube. We also evaluated all these platforms in two other key areas: how the source content (or ‘inventory’ in the parlance of feed algorithms) and the data features used to rank different content items.

Our goal was to put all these pieces of information together into a visual representation—a ‘nutrition label’ for feed algorithms. We call the result a ‘feed card’—a prototype visual framework for evaluating these parameters. The visualization seeks to explain how the feed is composed, what features it is most significantly based on, and the extent to which different optimization goals are prioritized.

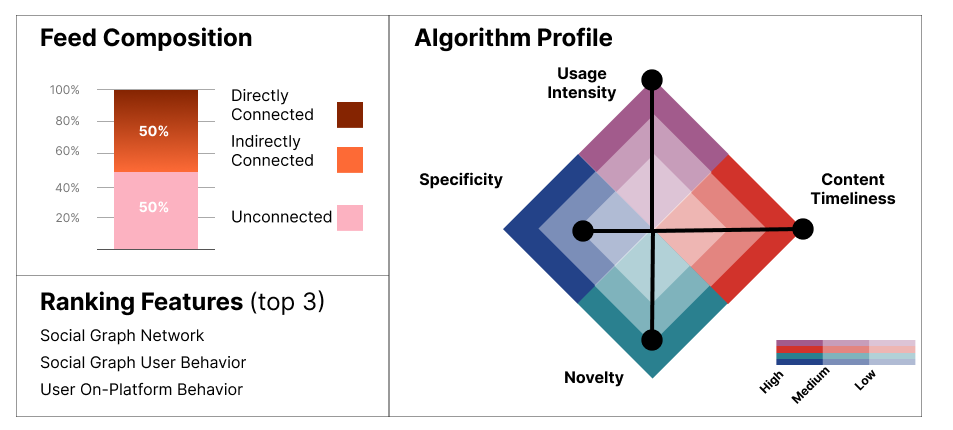

To show you a couple of examples, a feed card for X looks like this:

Feed card illustration: Laura Edelson, Frances Haugen, & Damon McCoy. Source

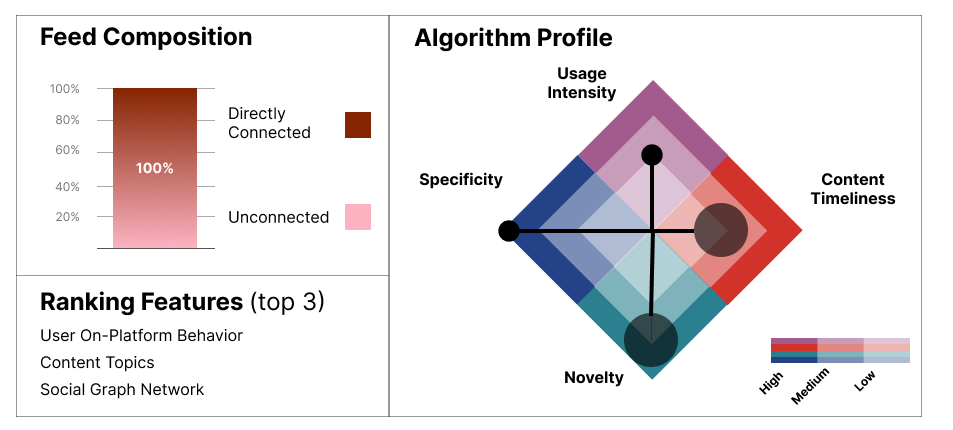

While YouTube looks like this:

Feed card illustration: Laura Edelson, Frances Haugen, & Damon McCoy. Source

Feed cards are designed not only to help users understand how a particular feed algorithm behaves, but also to be able to compare two different feeds, and understand why they might feel different from each other.

In our paper, we use the central analogy of cars to explain how different parts of social media feed algorithms work. Just as different vehicles are built for different environments and different purposes, social media companies’ business models drive the design decisions that algorithm designers make. Also, like cars, sometimes the best choices for safety aren’t the most profitable ones. We don’t yet know exactly how to make social media safer for users, but it’s clear that as they are, feed algorithms do pose risks for some users. We hope that this framework will allow us to have more useful public conversations about social media feeds and enable better research into user safety. Because if there’s one other thing we can all agree on about social media, it’s that it needs to be better.

Read the full paper at the Knight First Amendment Institute.

Authors