Why Free Trade Agreements are the Best Bet in the Absence of Multilateral AI Governance Forums

Shweta Kushe, Shivangi Mugdha / Dec 23, 2025

Detail from Digital Society Bell by Lone Thomasky & Bits&Bäume. Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

Few moments in human history mark as clear a turning point as the invention of artificial intelligence. Today, AI is disrupting economies even as it promises to reshape society. But the architecture of global trade remains unprepared, despite the fact that AI applications rely on a deeply interconnected global supply chain including US-designed and Taiwanese-fabricated semiconductors, American-dominated cloud platforms, and vast datasets harvested from around the world.

In a time when multilateralism is in retreat, the absence of a coherent international framework for AI governance and trade poses serious risks. While the World Trade Organization (WTO), which was primarily designed for goods trade, possesses a limited trade-related mandate over digital services, neither it nor any agency of the United Nations has the complete institutional capacity or political traction to regulate or build consensus on all aspects of data-driven technologies. In terms of realpolitik, given the competing regulatory philosophies of the United States, European Union and China, a global AI treaty appears improbable, if not impossible.

This presents a clear pivot point: Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) must become the new laboratories of AI governance — frameworks capable of embedding interoperability and accountability into the fabric of global trade, one bilateral agreement at a time. They are not a substitute for multilateralism. However, right now, they are the only viable mechanism to harmonize AI regulation and enable predictable, lawful AI trade.

The global supply chain of AI

The AI supply chain exemplifies the deep interdependence on which the modern digital economy survives. At its foundation lie semiconductor chips, the physical nervous system of artificial intelligence, whose architectures are primarily designed by leading firms in the United States. Fabrication, however, is concentrated in Asia, with Taiwan and South Korea holding an overwhelming share of advanced logic and memory chip production. These chips are subsequently integrated into global data center networks, powering the computational infrastructures that underpin large-scale AI models. Much of this infrastructure is then operated by American hyperscalers, who dominate the market for AI model training and cloud compute capacity.

The AI models that run on this infrastructure are trained on vast datasets collected across continents, governed by an array of privacy and intellectual property regimes. Finally, these models are deployed through application layers that reach consumers in virtually every market.

Every stage of this process is subject to a mosaic of regulations. Export controls limit who can buy advanced chips; data protection laws and intellectual property frameworks dictate how training material is handled; source-code accountability provisions determine how the resulting models are evaluated. The problem here is not regulation itself, but regulatory dissonance. An AI product can be lawful in one jurisdiction, non-compliant in another, and geopolitically sensitive in a third. This results in a patchwork compliance landscape that discourages innovation across borders.

The end of multilateral optimism

The assumption that the WTO or another global institution would eventually extend its reach to digital technologies has proven misplaced. Efforts to create a multilateral framework for e-commerce have already stalled due to a procedural rule that lets a single member block plurilateral progress at the WTO. The politics surrounding AI are even more polarized, leading some to advocate for the creation of sovereign AIs to navigate this landscape.

Organizations such as the OECD, UNESCO, and the G20 have developed principles for ethical AI, but these are non-binding and largely aspirational. There is no global enforcement mechanism, no dispute-settlement process, and no agreed-upon definitions of high-risk or critical AI systems. The United Nations’ recent resolution on AI marked symbolic progress, but it lacks teeth. On the other hand, the EU’s rights-based approach, China’s state-centric approach and the US’ market-driven model rest on divergent premises, making it difficult to find consensus on AI governance.

As Emma Klein and Stewart Patrick argue, the world is developing a "regime complex" for AI, with many overlapping and sometimes competing initiatives, but no central body to coordinate efforts or resolve disputes. Unlike global trade, which has the WTO, or telecommunications, which has the International Telecommunication Union, AI lacks a dedicated forum for negotiating binding international rules.

Given this fragmented global governance, bilateral instruments like free trade agreements have the potential to become the primary architecture through which nations shape global rules of AI.

How much have Free Trade Agreements achieved in the AI space until now?

One of the earliest trade agreements to have even mentioned artificial intelligence was the China–Mauritius Free Trade Agreement, which was signed in 2019 and brought into force in 2021. However, the provisions contained merely a passing reference to AI and were not substantively tied to the development or deployment of AI systems. Consequently, according to the Trade Intelligence and Negotiation Adviser (‘TINA’) database by UNESCAP, the first FTA to dedicate a stand-alone article to artificial intelligence was the Australia–Singapore Digital Economy Agreement, 2020. This provision is emblematic of the ‘endeavor-based’ style that now dominates the landscape. Under such ‘endeavor-based’ provisions, parties confine themselves to best-effort commitments to cooperate, exchange information, or promote responsible use, without assuming binding obligations or enforceable disciplines.

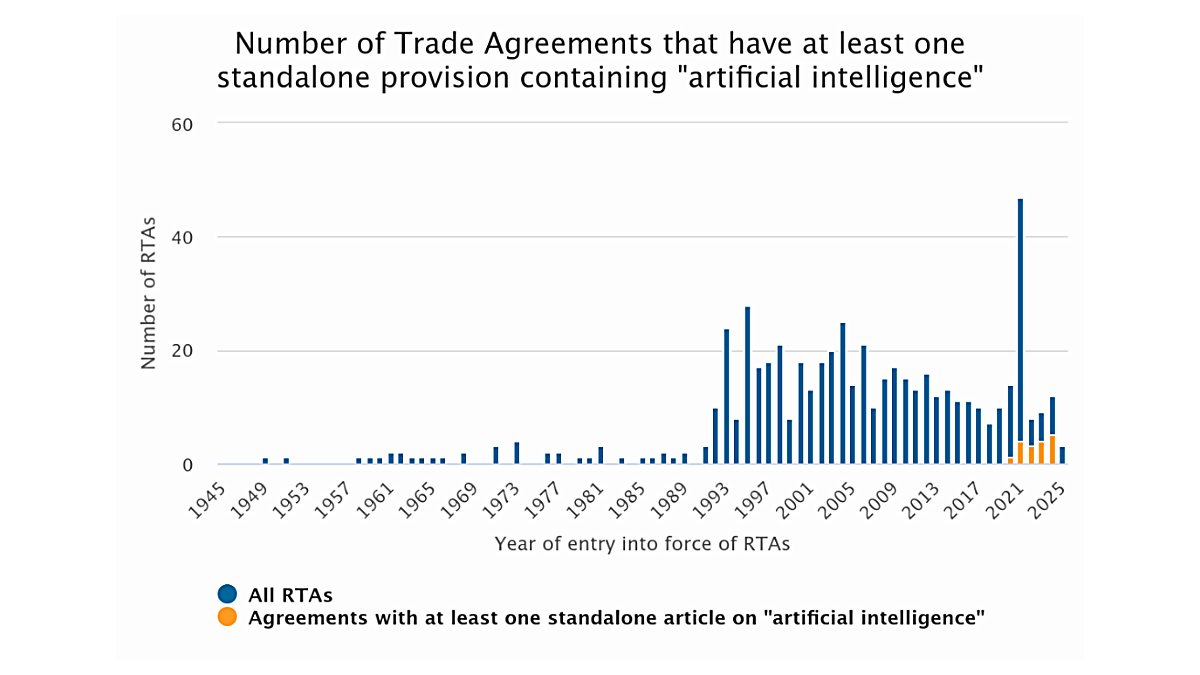

Source—TINA, UNESCAP

After 2020, while a large number of trade agreements mentioned ‘artificial intelligence’ in some context, only 18 trade agreements provided for AI to some extent; the language of these provisions is largely aspirational and endeavor-based. According to WTO’s World Trade Report, as of October 2025, only 2 per cent of all Regional Trade Agreements and Digital Economy Agreements worldwide incorporate any explicit AI-related provision. These clauses generally acknowledge AI’s potential for social and economic benefit but rarely move beyond declaratory intent, mirroring how e-commerce was acknowledged but not institutionalized in the early days of trade policy.

In most cases, AI appears alongside digital policy issues such as cross-border data flows, data localization, and source-code protection. Only a handful of newer agreements are beginning to address substantive issues, for instance, they require Parties to permit cross-border data transfers, including personal data, for business purposes, while still recognizing each Party’s sovereign right to maintain its own regulatory safeguards. Similarly, several RTAs now prohibit data localization measures, except when necessary to achieve legitimate public policy objectives, and ban mandatory source-code transfers for mass-market software as a condition for market access.

While not AI-specific, these provisions shape the regulatory environment in which AI systems operate. They determine where and how training data can move, whether AI developers can access computational infrastructure abroad, and how accountability mechanisms can function across borders. Yet, as the WTO has observed, only a small fraction of these agreements address AI governance per se, for example, the ethical use of algorithms, explainability, or the need for shared audit frameworks. So, the need of the hour is more direct and enforceable integration of AI governance principles within trade agreements.

What kind of specific provisions can trade agreements have?

To prevent FTAs from deepening the asymmetry between countries that develop AI and those that merely consume it, provisions must be crafted carefully. To begin with, most trade agreements fail to define AI-related terminology with precision, leaving key concepts open to interpretation and uneven implementation. Future agreements should clearly define terms such as “foundational model,” “high-risk AI system,” “training data,” and future-proof these definitions through a scheduled review mechanism and an annex that can be amended by a joint committee formed by the signatory countries.

It is understood that the prevalence of endeavor-based language often reflects a lack of precedent or consensus. But, herein, the use of “shall endeavor” clauses should be accompanied by clear timelines for transitioning toward binding commitments. This, in turn, requires the creation of a Committee on AI and Digital Trust, a standing body created within the scope of the FTA, with the authority to adopt or update technical annexes, interpret treaty provisions, conduct joint audits where necessary, and ensure compliance with global norms.

Beyond institutional design, FTAs need AI-specific provisions that support both sovereignty and interoperability. Here are some possibilities:

- Harmonization of cross-border data governance commitments: Data is the raw material of AI, and its governance determines whether the AI ecosystem can flourish. FTAs should introduce interoperable data governance frameworks that:

- Allow trusted cross-border data flows while preserving a party’s sovereign right to protect sensitive datasets.

- Include binding commitments that allow parties with nascent AI ecosystems to access anonymized, high-quality datasets, benchmarking tools, and documentation from advanced partners.

- Access to compute: Given that compute capacity is foundational for model development, FTAs should require that:

- Parties ensure predictable, affordable, and non-discriminatory access to computing resources necessary for the development of sovereign AI models, to the extent possible.

- Any party introducing export controls on semiconductor chips, compute infrastructure, or AI accelerators shall notify the other parties no later than a mutually agreeable period before implementation, except in urgent national security circumstances.

- Critical AI-related infrastructure may, by mutual agreement, benefit from simplified customs treatment for hardware and other inputs, subject to end-use safeguards and scrutiny.

- Development of shared sovereign model ecosystems: To foster innovation, FTAs should allow parties to:

- Jointly fund or co-develop sovereign or semi-sovereign foundation models for public-interest sectors.

- Ensure that jointly developed models shall incorporate open benchmarking standards, shared evaluation datasets, and interoperable architecture to allow sovereign fine-tuning by each party.

- Negotiate narrowly tailored tax exemptions for data centers and other strategic infrastructure when such infrastructure is used for sovereign models or public-interest AI.

- Provisions on source code, model weights and algorithmic accountability: current digital trade chapters across trade agreements prohibit forced source-code disclosure but remain silent on AI model weights, safety documentation or auditability. FTAs should:

- Clarify that nothing in source-code non-disclosure provisions prevents a party from requiring information on energy consumption, security architecture, or resilience performance of AI-relevant infrastructure.

- Require transparency for high-risk or public-impact AI systems, including cross-border access to audit logs, explainability artifacts and system behavior summaries.

- Establish reciprocal obligations for notifying AI safety incidents, systemic model failures, or algorithmic risks that may cross borders.

The way forward

Free trade agreements have the potential to become active sites of experimentation wherein countries can pilot enforceable AI norms. If negotiated with clarity and actionable intent, these agreements can lay the groundwork for a future multilateral framework that is built slowly through practice and trust.

***

The authors express their sincere thanks to Anoushka Roy, whose insights on an early draft strengthened this piece.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not reflect the views of their employers or affiliated entities.

Authors