Who’s Afraid of the PRC? A Look at the China Hawk Movement

Jessica Kuntz / Oct 2, 2024Jessica Kuntz is an Associate Partner in Albright Stonebridge Group’s technology policy team.

Former Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R-CA, Ret.) and Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI, Ret.) during a hearing of the Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party. Source

In January 2023, the newly convened 118th Congress established the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In a Fox News op-ed announcing the formation of the Select Committee, former Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R-CA, Ret.) and Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI, Ret.) – who now runs Palantir’s defense sector operations – called on the US to end its economic dependencies on China, declaring the Chinese President Xi Jinping was pursuing an “aggressive agenda aimed at the pilfering of the American economy, destruction of our international leadership, and the subversion of our institutions.”

The increasingly central role of this sentiment in driving US foreign, economic and industrial policy brings with it real risks for the US, to include increased risk of military conflict, reactive and shortsighted policymaking, and warped priorities. But as technologists, policymakers and researchers try to craft some kind of international governance system for AI – a headline topic at the UN General Assembly in New York last week – understanding the driving forces and fears undergirding the China hawk movement remains key.

The entrenched anti-PRC movement didn’t spring from nothing – it was preceded by years of increasing Chinese espionage against the US, including a successful cyberattack on the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), rising concerns about Chinese IP theft against US companies, and Chinese provocations in the South China Sea. The Trump presidency put a newly negative narrative on China front and center. Chinese oppression of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang, wolf warrior diplomacy, and China’s condonation of Russia’s war in Ukraine piled on.

In May 2020, Republican members of the House formed the China Task Force – spurred at least in part by accusations that China covered up the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus and was to blame for the pandemic. The Task Force’s report identified six so-called CCP-related challenges: ideological competition, supply chain, national security, technology, economics and energy, and competitiveness. Writing in September 2020, the technology section of the report focused on countering Chinese 5G infrastructure, with lesser attention paid to the need to secure western leadership of “technologies of tomorrow, including AI, quantum, 5G, and autonomous vehicles.”

The rapid rise of China critics coincides with the rapid advancement of AI technology. It is hard to overstate the degree to which this correspondence has shaped the way in which governments frame AI risks and opportunities—US policymakers and developers acknowledge that AI brings risk. But the risk of losing out to China, almost universally, appears to outweigh any other possible risk.

The classification of China as a strategic threat is the driving force behind the increasingly complex web of export controls and investment restrictions—begun under the Trump administration but hardened under the Biden administration—on AI hardware and other critical technologies. The Biden administration has framed these restrictions as a “small yard, high fence” approach—one of economic de-risking, as opposed to more comprehensive economic decoupling. Technology companies serving Chinese clients, as well as those that, in the seemingly distant era of friendly US-Sino relations, incorporated low-cost Chinese operations into their global supply chain, now find themselves caught in the tailwinds of economic nationalism.

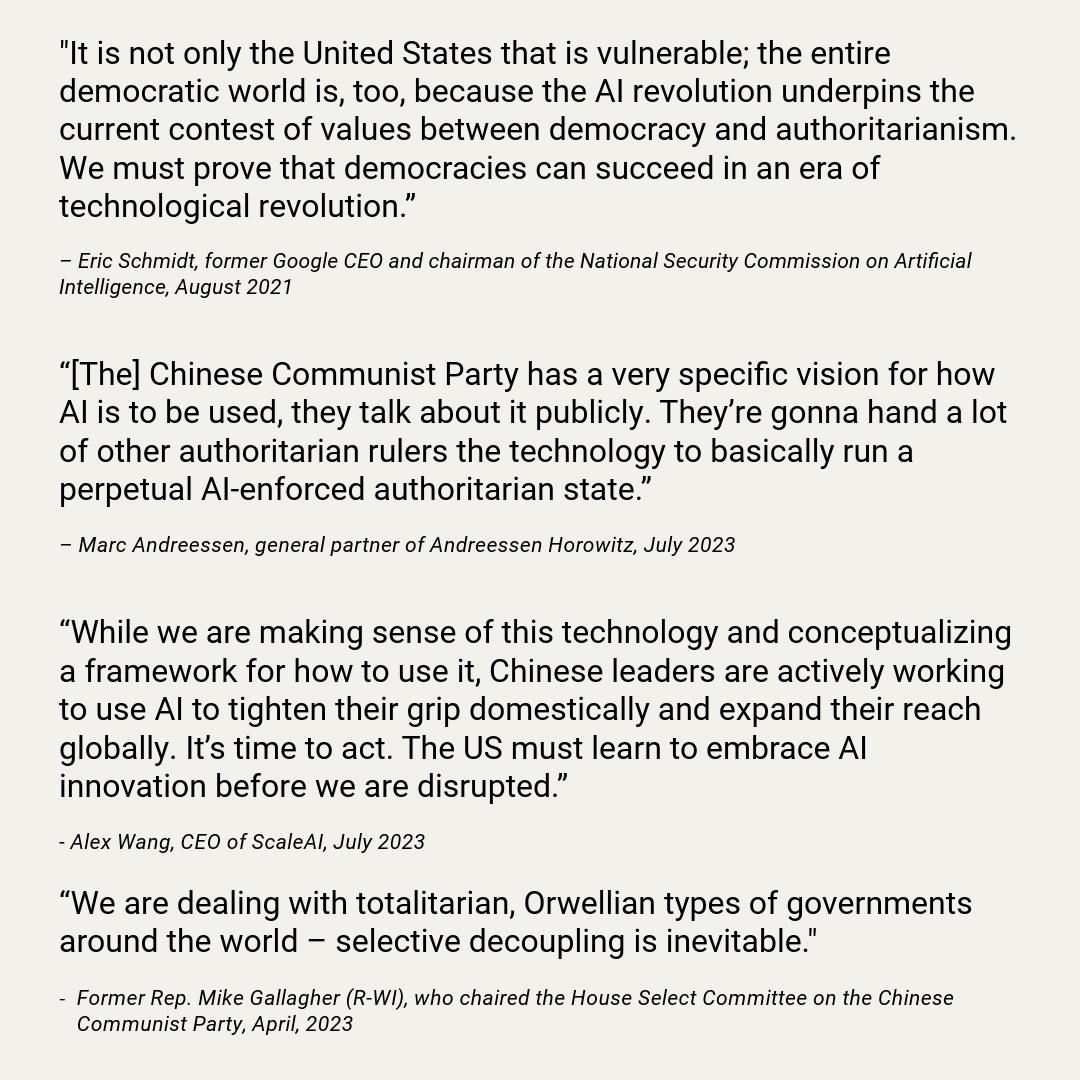

Sources: Schmidt, Andreessen, Wang, Gallagher.

Increasingly, AI industry leading voices have mirrored the anti-China talk of Washington. Palantir, an early Silicon Valley firm to integrate itself with the US government as a contractor, built its business model around a pro-Western world view. Speaking at Davos in 2023, Palantir co-founder Alex Karp left little to the imagination, stating that “we want people who want to be on the side of the West.” In July, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman echoed Karp’s rhetoric in a Washington Post op-ed. The emerging contest to control AI, he wrote, is between authoritarian and democratic nations. If we wish to fully realize AI’s benefits—and avoid a world in which US companies are forced to share user data with authoritarian nations who use it for surveillance and cyber warfare—we must take steps to “make sure the democratic vision for AI prevails,” according to Altman.

A recent report by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF), an industry-funded, pro-business think tank, argues that, contrary to the traditional view of China as a mere copier of foreign developed technology, the Chinese ecosystem has proven itself to be quite adept at innovation across a range of emerging technologies, including robotics, quantum, semiconductors and AI. The report goes on to argue in favor of the US “adopt[ing] key elements of the China model and embrac[ing] ‘national power capitalism’”—wherein increased government involvement and capital enables greater risk taking in pursuit of innovation. This perspective will undoubtedly find a ready audience with China hawks on Capitol Hill, primed to see Chinese capabilities in the most threatening possible light, for whom China’s innovation capabilities will be viewed as cause to redouble efforts to cut China off from the tools, equipment, and even training underlying advanced technologies.

The Chinese threat remains the rare issue that generates consensus across bipartisan lines on Capitol Hill. But what exactly we fear from an AI-equipped China is rarely articulated in any detail. Elected officials—and figures like Altman—warn of AI-powered surveillance and oppression, the integration of AI into defense technology, and the use of AI to conduct cyber-attacks, but much is left to the imagination. At the Politico AI & Tech Summit, Scale AI Managing Director and former CTO to President Trump Michael Kratsios framed the stakes of the global AI competition in terms that recall a 5G redux, warning that China would subsidize its AI systems to beat out Western alternatives, embed its technologies across the Global South and siphon off sensitive personal data. Kratsios endorses a strategy encompassing defensive export restrictions alongside an offensive strategy entailing government promotion of US AI technologies overseas.

The rhetoric of the most adherent China hawks often trends towards paranoia, with China cast as an almost bogeyman-like figure. But with China critics positioned to maintain influence regardless of the election outcome in November, politicians on both sides of the aisle are wary of being labeled as “soft on China,” feeding the distrust lapping the bilateral relationship between the world’s two dominant powers.

Authors