Who Will Own TikTok in the US and Why it Matters for Democracy

Tim Bernard / Dec 15, 2025

President Donald Trump greets Chinese President Xi Jinping before a bilateral meeting at the Gimhae International Airport terminal, Thursday, October 30, 2025, in Busan, South Korea. (Official White House photo by Daniel Torok)

Despite the TikTok sale-or-ban law coming into force the day before United States President Donald Trump’s inauguration this past January, TikTok remains available to US users. Trump’s stated justification for the delayed enforcement of the law was “so that we can make a deal to protect our national security.” This deal, whereby ByteDance would divest TikTok's US operations to non-Chinese ownership, has been taking shape ever since, with snippets of information released to the public over the months.

Various investors are reportedly under consideration or in preliminary agreement to purchase the US operations of TikTok. While other suitors, including Amazon, have also expressed interest, a consortium of investors, including Oracle, seems most likely to prevail. Recent reports have also highlighted private equity firm Silver Lake and the Emirati tech fund MGX as key players; earlier reporting mentioned the venture capital fund Andreessen Horowitz and private equity firm Blackstone, and Trump has also mentioned the possible involvement of Rupert Murdoch, Lachlan Murdoch and Michael Dell. ByteDance and its current investors may also acquire shares in the new entity.

Authoritarians have long sought to control the media in order to influence public opinion. The situation in Hungary is a cautionary tale for how this approach can be harnessed in the course of democratic backsliding. The Trump administration’s actions—including towards CBS in its acquisition bid, the current FCC’s approach to “media bias,” and the president’s lawsuits against the New York Times and CNN—indicate an eagerness to suppress media criticism. With Trump’s active political backers amongst the purported investors in a new TikTok entity, not to mention the owners of Fox News, there is good reason to ask questions about the implications of a White House-brokered deal for the content on TikTok, and for American democracy.

But the details matter, and these remain unclear, including the final balance of ownership between different parties. TikTok’s share distribution may be consequential for the content that will be permitted on the platform after the acquisition as well as what may be amplified or reduced.

In a new paper, platform governance scholar Paddy Leerssen of the University of Amsterdam’s Institute for Information Law draws on research in traditional media ownership and public financial records to analyze the current landscape of platform ownership and how it impacts content governance.

Platform ownership and content policy

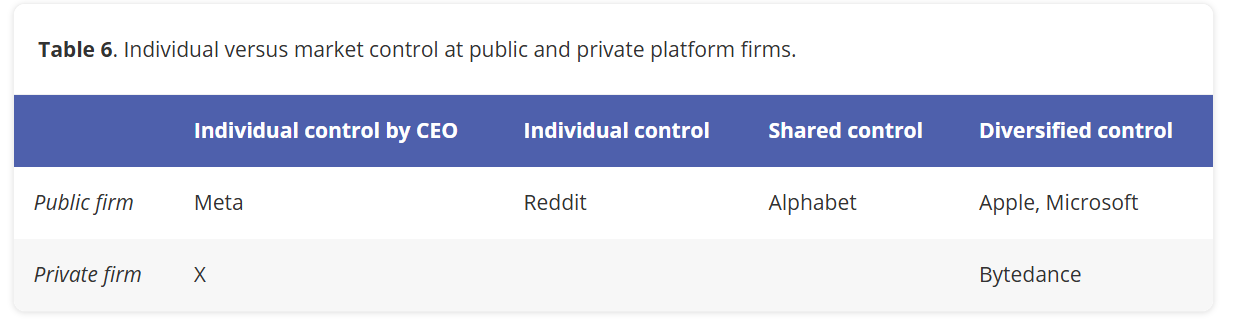

Leerssen has classified the platforms’ control models. X is at one extreme: a private company under the control of one individual who is also its manager (although Elon Musk is not technically the CEO of X, he is the CEO of xAI Holding Corp., X’s parent entity). At the other are Apple and Microsoft: public companies with institutional investors having the largest shares. The platforms in between run the gamut: Meta, a public company with a largest-shareholder CEO who retains overall control of the company thanks to a dual-class share system; recently-public Reddit, where the majority shareholders proxy their board votes to the CEO; Google parent Alphabet, a public company with individual owners sharing control; and the private ByteDance, which is (as far as Leerssen can tell) majority-owned by institutional investors.

Leerssen, P. (2025). "From Murdoch to Musk: Platform ownership and the political economy of online content governance." Platforms & Society, 2.

Positing that “different ownership forms yield different institutional logics, or sets of practices and values that act as organizing principles,” Leerssen then explores what we know about content policy decision-making at these platforms and how it relates to their ownership model. In particular, he discusses how “private logics” and “market logics” play out in these companies.

Private logics reflect a “diverse and erratic set of (oligarchic) personal preferences.” While some sole controllers are less forthcoming about their perspectives, Musk has not hidden his own politics and his desire to make X a better platform for himself and a less friendly environment for his political opponents, and this has resulted in a plethora of decisions, many of which are no doubt familiar to Tech Policy Press readers. Mark Zuckerberg, the other billionaire who both controls and manages his platform, has reportedly undergone a significant transition from being less interested in content policy to overriding decisions, promoting himself when he was reportedly considering entering politics, and directing a shift away from fact-checking and regulation in an early 2025 right-wing turn.

Market logics, on the other hand, are focused on maximizing profits or shareholder value. These should be less influenced by personal politics, and more inclined towards cost-cutting and automation, balanced by brand safety. However, there is a large set of potential commercial pressures on platforms, including political and regulatory risk. “As such,” Leerssen cautions, “singling out certain firms as departing from market logics requires some caution; there is after all very little consensus on what ‘ordinary’ commercial moderation looks like.” Much of Zuckerberg’s—and even Musk’s—intervention in platform policy could also be explained, at least in part, by economic concerns for the company (or network of companies in Musk’s case). Correspondingly, YouTube (Alphabet) and LinkedIn (Microsoft) also shifted policy slightly rightwards in 2025, he writes.

Further complicating the picture, institutional investors have political-economic concerns of their own, including Vanguard and BlackRock, which are some of the largest investors in all of the public platform companies in the study and who have flip-flopped on ESG, indicating their susceptibility to political winds. As Leerssen summarizes: “[p]latforms and their content governance thus operates in a field of increasingly politicized struggle between various financial actors and institutions, including Silicon Valley's tech moguls but also (broadly Democrat-aligned) banks and investment funds and (broadly Republican-aligned) private equity groups.”

Leerssen also identifies a third force in the “professional logics” of trust and safety workers. Even though these professionals are not protected from their owners by any formal “firewall,” as is common in journalism, they may retain some degree of autonomy, in part deriving from the complexity of the systems they operate. The location of a trust and safety function within the company organizational chart may also bring different incentives to bear and help determine how well-insulated it is from owner influence.

Who will control TikTok US?

According to reporting from CNBC in September, Oracle, Silver Lake, and MGX are expected to own 45% of the new entity, ByteDance will retain 19.9%, and other investors, including the VC and PE firms KKR, Sequoia and Susquehanna, will take the remaining 35%. Despite the possibility of individuals like Rupert Murdoch and Michael Dell acquiring stakes in TikTok, it will not be possible for them to control the new company in whole or in partnership if the reported share distribution holds.

As Forbes lays out, many of the investors have links and overlapping interests with Trump, though it appears that well over half of the company will be owned by institutions that are beholden to their shareholders to make their investments grow—in contrast to some of the steps taken by Musk that may have contributed to advertiser flight. Even for Oracle, which is substantially owned and controlled by Trump ally Larry Ellison (41% owner and both executive chair and CTO), the stake is reportedly being acquired through the public corporation rather than in Ellison’s personal capacity.

Even if leadership of the entities owning a controlling share of TikTok are supportive of pushing content policy in a rightward direction, market logics may still play a dominant role due to fiduciary responsibilities to their own investors. Tiktok’s young user base has also made safety a strategic priority for the company, mitigating against loosening of rules. The sheer number of organizations that will need to be on the same page regarding policy direction may also prove to be an obstacle to private logics playing out. On the other hand, the personal positions of leadership may tip the balance when politics and economics arguably align.

Finally, TikTok has a large and multi-layered trust and safety team and an intricate management structure. Much of TikTok’s engineering is China-based, and it remains to be seen how much a new US policy team will rely on Chinese engineers. Complexity here may serve as a further impediment to steering policy in the preferred direction of the owners. Presumably a new entity will install a new CEO and simplify reporting chains for the US trust and safety function, but much is unknown in this regard.

Leerssen emphasizes that a lot more analysis is required before firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the impact of platform ownership on content governance. Missing facts include the opinions of less vocal owners, the shareholder breakdowns and control agreements of private companies, and potential gaps between official policy and operationalized enforcement.

Taking these lacunae together with the unknowns about the TikTok divestment, which still has not been fully approved by the Chinese government, it is far too early to reach any conclusions about how the new ownership will play into the Trump administration’s encroachment into media independence. Given the context, however, it is by no means too early to start thinking about it, and Leerssen’s paper provides important background for considering the broader implications of the deal.

Authors