Where You Look Is Personal

Joseph Jerome / Jun 6, 2023Joseph Jerome is a privacy attorney in Washington, D.C.

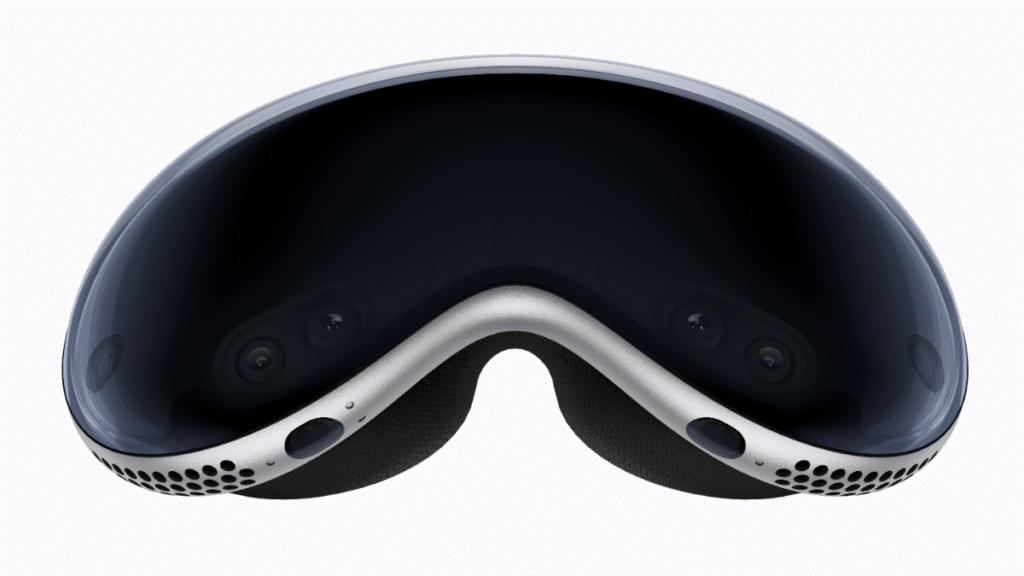

This week’s reveal of Apple's Vision Pro mixed reality headset demonstrates once again how much sensitive information will be needed to make more usable immersive technologies. One area worth more attention is the device’s technical capacity to create a user experience driven by a person’s eyes, hands, and voice.

Whether we are talking about VR headsets or AR glasses, these technologies will be fueled by the collection of body-based data. This information is necessary for this tech to function, but the ability of this data to be used for what’s been called biometric psychography or to further infer sensitive data about users presents a major concern.

The specific privacy implications of eye tracking have received much attention by both researchers and in the popular press. At a basic level, eye gaze can indicate our general level of interest in what we look at. Eye movements can be used to infer a person’s age and gender, as well as medical conditions, fatigue, or other impairments. While there may be other ways for companies to learn this information, gleaning these insights from eye data is problematic because of how involuntary many of our eye movements can be.

We often don’t realize how little control over our eyes that we have. Companies may argue that eye tracking should be treated as analogous to mouse movements, but we don’t realize how little control over our vision we truly have. Eye movements are also harder to disguise. For instance, my mouse was hovering over my desktop menu when I originally typed this sentence. My eyes? They've not just fixated on the last letter I typed, but have darted over to my television and plenty of other places I cannot consciously recall.

The initial use cases for eye tracking in VR sound innocuous enough: avatars that can make eye contact and better graphics rendering where the eyes are directed. The technology also offers accessibility benefits, but it is clear that companies are interested in using eye tracking to engage in attention monitoring, behavioral analysis, and, yes, advertising.

Apple has become a master of shaping external privacy debates, and it’s noteworthy that Apple focused on privacy protections around eye data in its public remarks on the Vision Pro.

When it comes to gaze data or eye input in Apple’s vernacular, the company is clear that these inputs are not shared with either Apple or any third party. “Only your final selections are transmitted when you tap your fingers together,” the company explains.

This is not the current industry standard. As Meta explained when it launched eye tracking on its Quest Pro last fall, the VR headset’s eye tracking APIs were anchored to the industry-wide OpenXR standard for inputs. OpenXR, an open API standard from the Khronos Group, has a suite of eye tracking APIs that require system and app-level permissions to enable eye tracking and generally facilitate sharing gaze information with third party applications.

Meta acknowledged that eye tracking raised important privacy questions and focused on the user transparency and controls it put in place. That’s not nothing, but as AR/VR commentator Avi Bar-Zeev noted at the time, Meta’s approach still puts the onus on users to protect themselves against misuse or just plain unexpected uses of gaze data. Meta isn’t actually out of step with the rest of the industry: various company approaches to eye tracking have also emphasized more transparency and more controls.

Apple’s approach to eye tracking sounds more like data minimization, which advocates will appreciate, and privacy by design, which should appeal to regulators.

There is more to learn. It’s notable that Apple focused only on the use of eye tracking as an input, and it’ll be worth doing a deep dive into developer documentation once it is available. Some of the underlying research and data models needed to build better eye tracking raise larger ethical considerations. Sterling Crispin, an Apple neurotechnology researcher for the Vision Pro, tweeted about the potential of using eye tracking as a “crude brain computer interface.” Advocates have warned what immersive technologies like augmented reality may mean for mental privacy.

That’s a bigger issue to confront, but for today, privacy advocates and enthusiasts for ethical XR should take a victory lap. Apple has not only given a boost to the AR/VR ecosystem, but it has also paved the way to push platforms to deploy more privacy-protecting APIs and minimize what body-based data it makes available to third parties.

Authors