What We Learned Running the Biggest Election-Related Fact-Checking Database in Europe

Stephan Mündges / Jun 13, 2024

People walk toward a banner advertising the European elections outside the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium on April 10, 2024. Shutterstock

Voters across the European Union just went to the polls to elect members of Parliament. While no major disinformation incident targeted the EU election process itself, the campaign leading up to the elections was accompanied by what can be described as the constant ‘noise’ of mis- and disinformation, including attempts by Russian-affiliated actors to tilt the scales, and domestic players leveraging disinformation narratives for their political goals. We tracked the misinformation landscape for months ahead of the elections using the biggest election-related fact-checking database to date. Though the verdict is still out on how significantly mis- and disinformation impacted the election results, here’s what we did, and what we learned.

In mid-February 2024, over 40 member organizations of the European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN) covering 34 European languages started ingesting fact-checks, disinformation, and their associated metadata into our database titled Elections24Check. It currently hosts data of more than 2,300 fact-checks and articles relevant to the election. European fact-checkers will keep ingesting data for the weeks to come to monitor any fallout from the elections.

Our goal was to gain a comprehensive overview of false claims circulating in EU member states but also in neighboring countries as disinformation does not stop at the external borders of the EU, unfortunately. And we wanted to create a platform that enabled our members to collaborate more closely and exchange information quickly. The project received support from the Google News Initiative.

Here are the main takeaways:

1. Climate change is a huge topic when it comes to disinformation in Europe

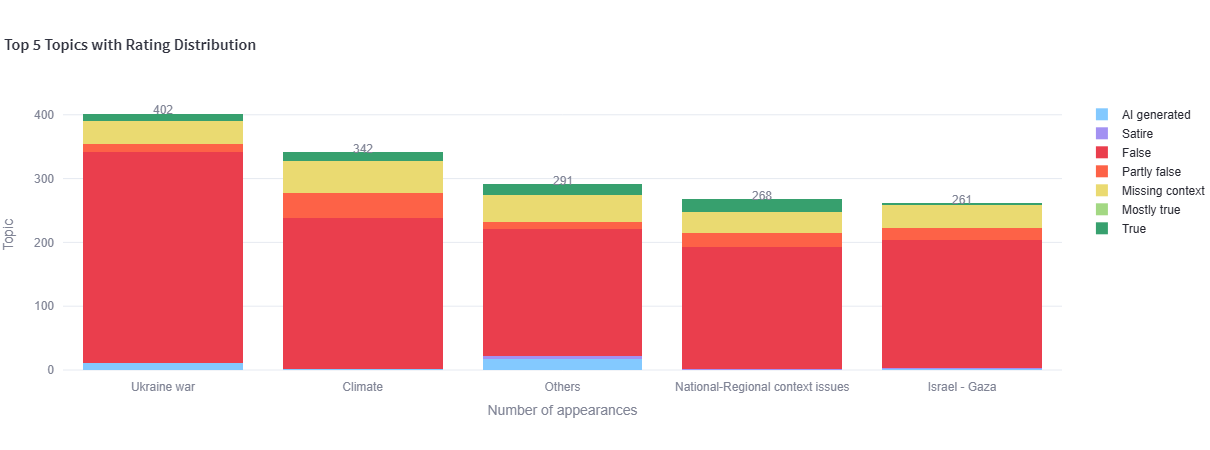

These are the most prevalent topics in the Elections24Check database:

We expected the Ukraine war to come up top of the list. What we didn’t expect was that false claims related to climate change would be second. False claims in our database range from the greatest hits of climate change-denialism (‘climate change is natural phenomenon!’) to very specific falsehoods regarding local countermeasures (‘Decrees against drought in Catalonia establish the expropriation of private swimming pools’) and to misleading claims against EU policies (‘the EU is going to ban the repair of cars older than 15 years’). The fact that farmers held numerous protests in several European countries in the months leading up to the election also triggered many fact-checks. An in-depth analysis by EFCSN members Newtral and Science Feedback showed that those protests were weaponized by a wide array of actors to spread climate misinformation and narratives undermining climate action.

2. Platforms’ responses to misinformation needs improvement

Using data from Elections24Check, Spanish fact-checkers Maldita.es evaluated how Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X and YouTube (all VLOPs under the DSA) responded to debunked misinformation surrounding the elections. To put it mildly, there is room for improvement. They found that 45% of misinformation posts received no visible action by the platforms, but each platform’s performance varies significantly. While Facebook and Instagram took visible action on the majority of posts (89% for Facebook, 71% for Instagram), TikTok, X, and YouTube did a lot worse. Read the full report here.

3. Disinformation is borderless

Elections24Check uses AI to cluster claims and identify overarching narratives from these clusters, which helps fact-checkers work faster and more efficiently. It also shows that across the European continent, similar claims circulate, cross borders and get picked up by different disinformers. For example, a change to the German penal code reducing the minimum sentence for child sexual abuse images was the subject of misleading claims in at least six countries.

4. Dozens of data points for each fact-check

All these insights are revealed by pooling fact-checks and false claims in one central database, auto-translating and enriching them with additional metadata. One should not underestimate the level of coordination this takes, especially in terms of harmonizing data structures and ensuring high quality data input across a diverse set of organizations. Fact-checking as a profession has made tremendous progress when it comes to journalistic quality assurance and common standards, but each organization still operates in their unique national or regional as well as organizational context.

One example out of dozens of data points we collected for every fact-check: most organizations use their own system to rate the accuracy of claims. To have comparability across the database, these rating systems had to be harmonized, and the harmonized system had to be consistently applied.

Next steps

Elections24Check taught us how to tackle these challenges, and we are already working on future iterations of a fact-checking database that offers even more data points. Elections24Check offers a first glimpse of the opportunities and insights such a database can provide to stakeholders, regulators, journalists, and trust and safety professionals. In the coming weeks and months it will be analyzed in further depth. We haven given access to the full dataset to more than two dozen researchers from universities and research institutes from all over Europe, who are already working to extract even more insights from the Elections24Check database.

Authors