We Know a Little About Meta’s “Break Glass” Measures. We Should Know More.

Dean Jackson / Oct 1, 2024Dean Jackson is a fellow at Tech Policy Press.

An image of a noose outside the US Capitol is is displayed on a screen during a meeting of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol in the Canon House Office Building on Capitol Hill on December 19, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Al Drago/Getty Images)

On September 26, 2024, five social scientists published a letter in the journal Science raising concerns about a 2023 study produced as part of a partnership with academic researchers to analyze Facebook and Instagram’s impact on the 2020 US elections. The study in question “estimated the effect of Facebook’s news feed algorithm on exposure to misinformation and political information among Facebook users” but “did not account for a series of temporary emergency changes to Facebook’s news feed algorithm in the wake of the 2020 US presidential election that were designed to diminish the spread of voter-fraud misinformation,” according to the letter’s authors.

These emergency changes–referred to as “break glass” measures–were aimed at slowing the spread of viral content and increasing the moderation of inflammatory posts, as The Wall Street Journal reported in October 2020. But, “[t]he exact effects and timing of most of the 63 break-glass news feed changes of 2020 are not known to the public," according to the authors of the letter to Science. In other words, they are concerned that the news feed study, which along with other studies produced by the partnership has been referenced by Meta as a proof point that the company’s platforms have less influence over politics and polarization than many assume, is compromised.

For their part, the study’s authors stand by their process and results, and point out that they cautioned that the findings were more nuanced, and the questions more complex, than Meta suggests. Ultimately, the issues raised in the open letter turn on what, precisely, Facebook’s “break glass measures” did and when they were in place. How did they interact–if at all–with the platforms’ recommendation algorithms and the spread of news or other political content?

Fragments of the answer

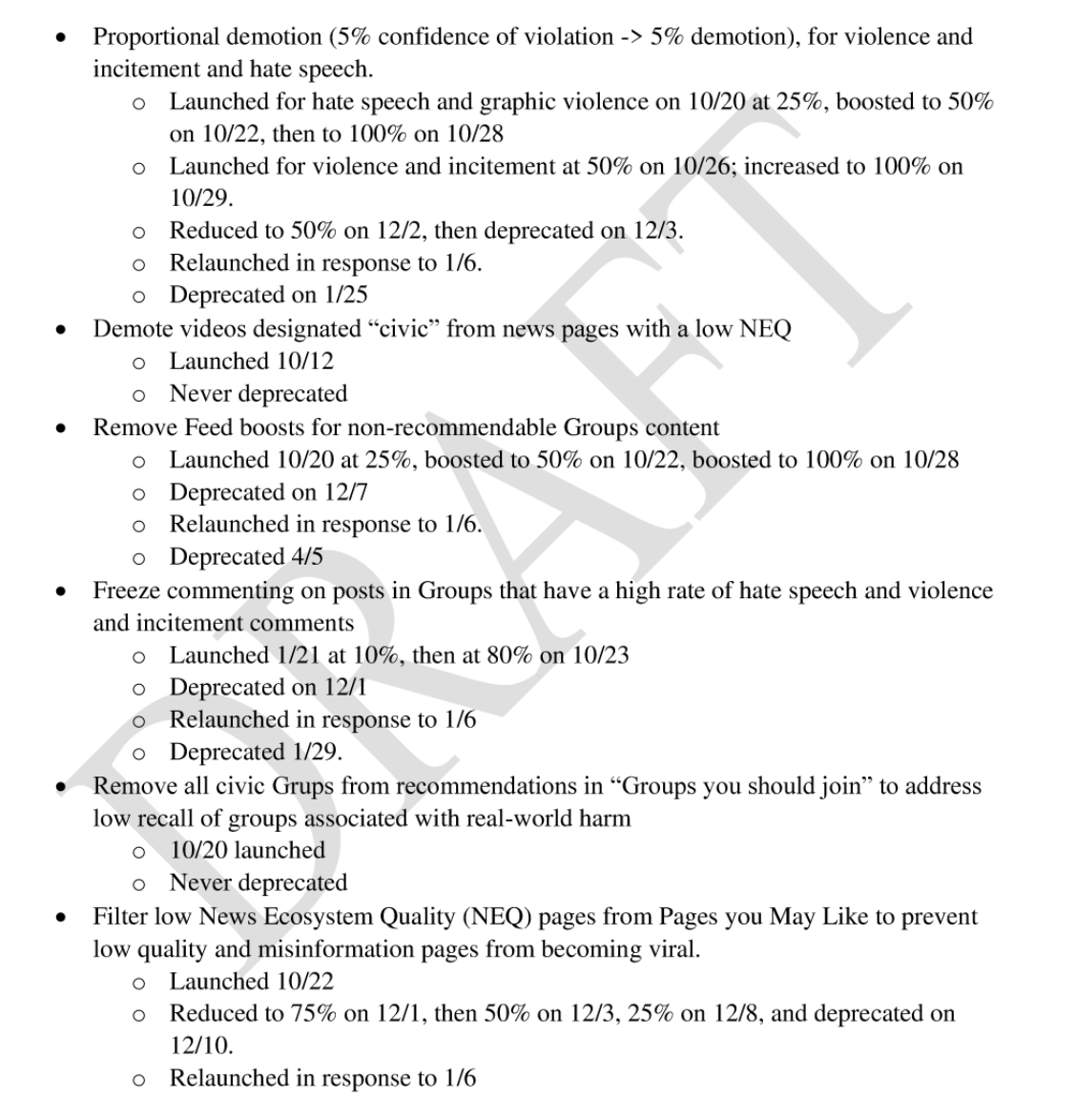

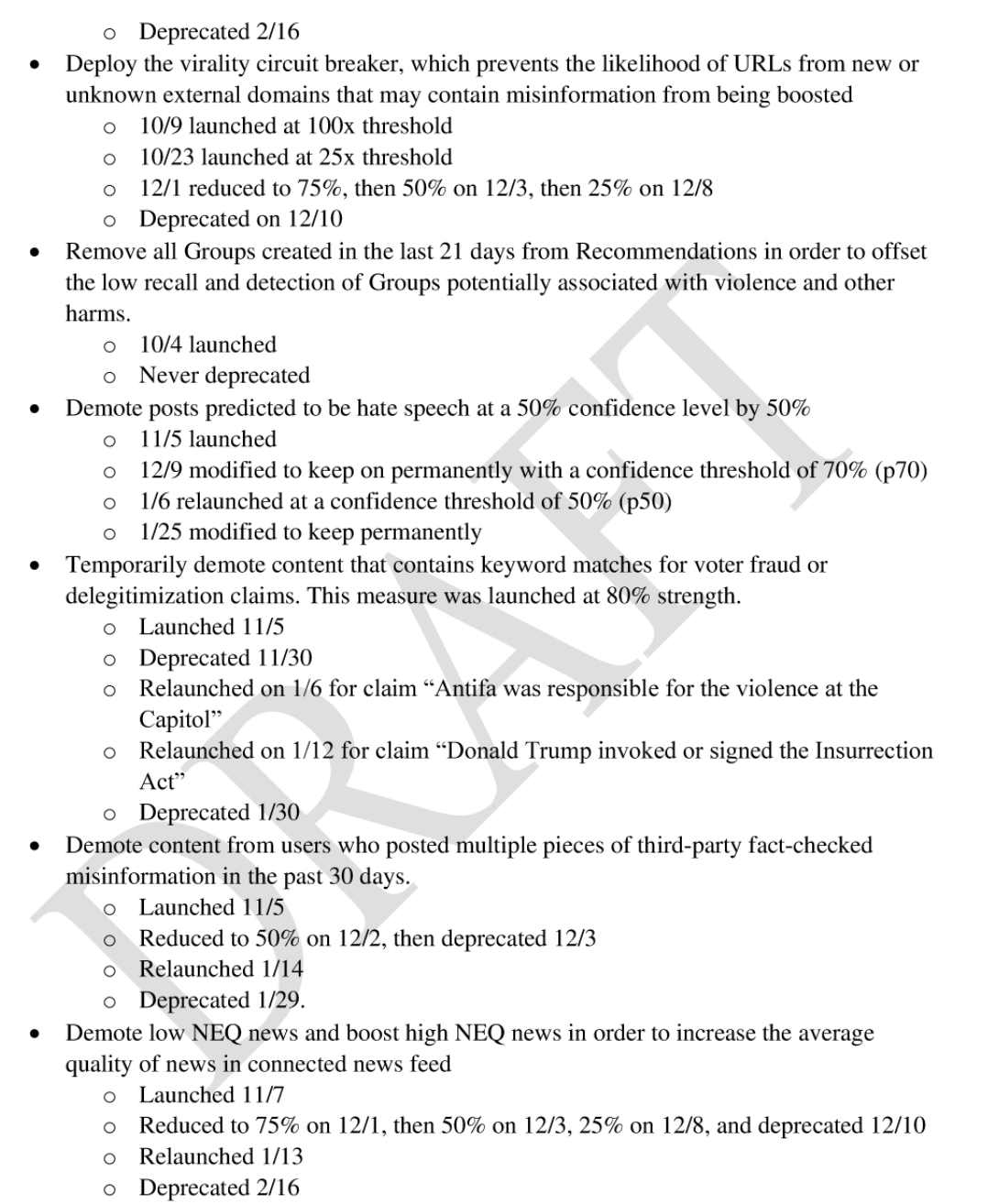

It should be shocking that in 2024, with the same lies about election fraud being peddled by the same presidential candidate, the public still knows very little about those emergency changes. But more information is available than many presume: a leaked memo from the House of Representatives Select Committee to investigate the January 6th Attack describes twelve of these measures, as well as their dates of activation and deactivation. (Full disclosure: I was one of the authors of that leaked memo.)

The leaked memo from the January 6th Select Committee sheds some light here. On page 34, a footnote reads that “a full list of the Break Glass measures deployed by Facebook, as well as the dates during which they were operative, has been made available to the Select Committee.” For reasons that are its own, the Committee did not report many of the findings of the investigative team focused on social media. That full list is not publicly available, but the leaked memo contains descriptions of 12 of those 63 measures.

Screenshots of the descriptions of twelve of Meta's “break glass” measures published in the leaked memo from the January 6th Committee.

What can be gleaned from these descriptions? First, some of the measures applied a process called “proportional demotion” to content which Facebook algorithms judged likely to be hate speech or violent incitement. This process demoted the distribution of content by a percentage equal to the confidence that Facebook’s automated systems judged it to be violative. If the degree of confidence was high, the degree of demotion would also be high. Internal Facebook communications suggest this was a highly effective measure for reducing online harms, but to capture the majority of violative content the platform would have to be comfortable acting on content that automated systems assessed with low confidence. In other words, the company’s vaunted automated content moderation tools were not very accurate. At first, company executives were hesitant to demote content based on these low-confidence assessments, but they gradually relented. However, these measures were rolled back in early December, only to be reinstated after January 6th.

A similar measure appears to have been applied to “content that contain[ed] keyword matches for voter fraud or delegitimization claims,” but was rolled back on November 30th and re-instituted after January 6th—then ended again at the end of January 2021.

Facebook also employed a measure called “news ecosystem quality” (NEQ) to rate news pages and demoted content from publishers with a low NEQ. As with the previous measure, many of these policies—which directly altered the quality of news content in user’s feeds—were deprecated after the election and re-instituted briefly after January 6. At least one, the demotion of videos from low-NEQ publishers, was never deprecated (at least, as of the creation of the document provided to the Committee by Meta). Similar steps were taken to reduce the circulation of content from users who repeatedly posted content rated false by third party fact-checkers; this measure was also rolled back in December only to be temporarily re-launched in January.

Other measures dealt with Facebook groups, which the memo (and leaked files from Facebook) singles out for driving the growth of the “Stop the Steal” movement in December 2020. Facebook made an effort to begin designating groups as “civic” if they discussed news, politics, and current events; this proved challenging, because non-civic groups can quickly become civic in response to offline incidents. Many neighborhood community groups became civic during the protests following George Floyd’s murder, for example, even if they previously had not been. Moreover, Facebook struggled to classify civic groups which were less than two weeks old—which many Stop the Steal groups were by definition. For this reason, all groups less than 21 days old were removed from recommendations, a change Facebook has never deprecated (to public knowledge). Other changes to Facebook groups were deprecated, however, after an internal study found they caused a high tradeoff between group growth and harm reduction.

We need independent research, not “independence by permission”

Overall, this sample of the break glass measures shows us that they were inherently tied to the concerns raised by the letter published in Science. They also vindicate allegations that Meta could solve the problem of untrustworthy information circulating on its platform if it optimized for news quality—something it has already studied.

The more important point, though, is that science cannot rely on the whims of its subjects—it cannot operate through “independence by permission,” as the US 2020 elections research partnership was dubbed by its independent ombudsman. It should not be up to Meta when, and to whom, it discloses the measures it takes to protect election integrity. The company is too powerful to operate with such a low level of accountability. That so little is publicly known about Meta’s 2020 election efforts that we are forced to rely on a series of company sanctioned studies is appalling. Perhaps worse is that there is no research partnership to study the 2024 election cycle, and that Meta has made it harder for academics to study its platforms.

It is far past time that real transparency and mechanisms for academic inquiry are imposed on platforms like Meta, on behalf of the public, by elected government representatives. Unfortunately, not only has Congress failed to act—but in the vacuum it has created, social media platforms have become more opaque than ever.

Authors