Want to Access Your Taxes Online? The IRS is Going to Make You Send a Selfie.

Patrick Lin / Jan 28, 2022Patrick K. Lin is the author of Machine See, Machine Do: How Technology Mirrors Bias in Our Criminal Justice System.

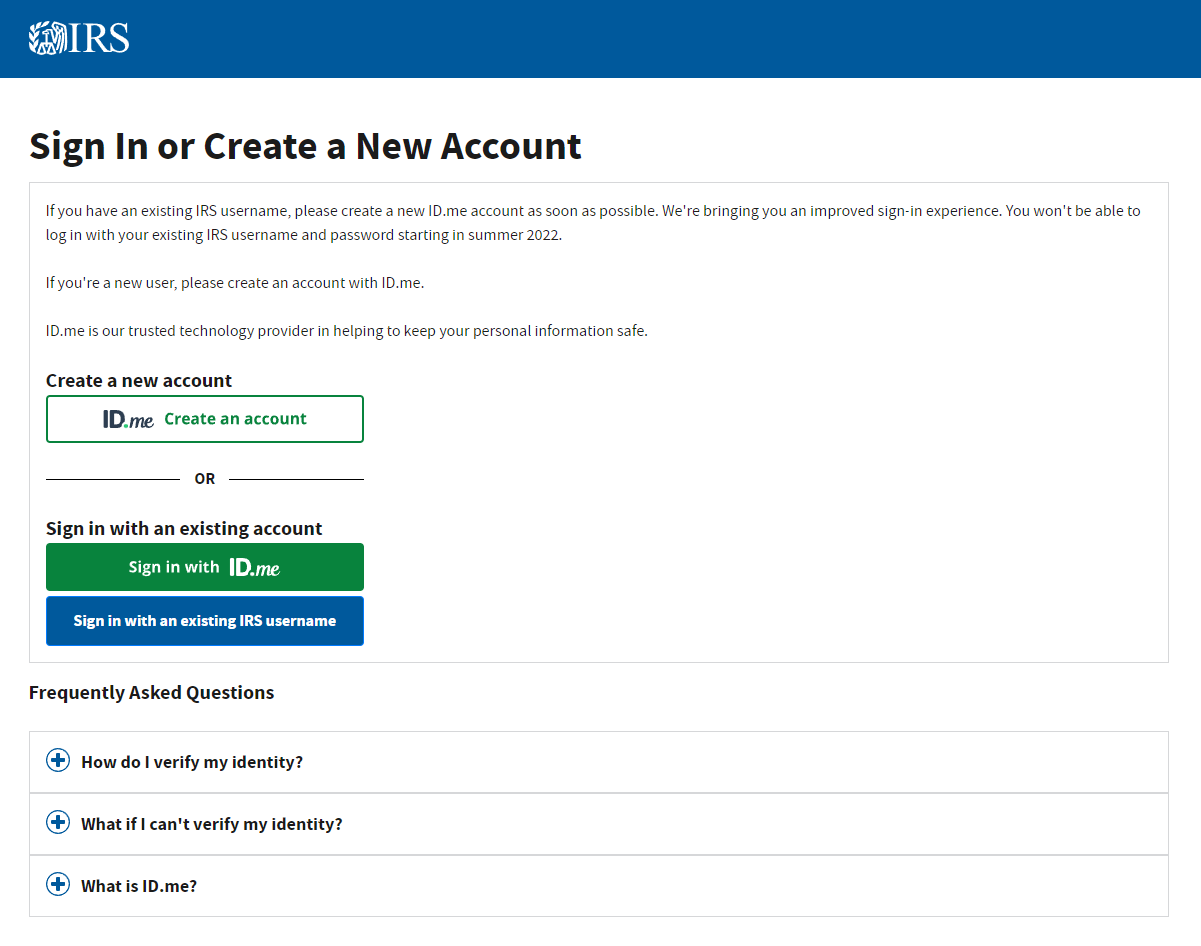

This summer, the IRS will require online tax filers to submit a selfie to ID.me, a third-party identity verification company, which will use facial recognition to provide access to IRS accounts. Last week, computer security blogger Brian Krebs was the first to notice an update on the IRS login page prompting people to create an account with ID.me. Per the IRS website, without an ID.me account, “[y]ou won’t be able to log in with your existing IRS username and password starting in summer 2022.” In order to create an ID.me account, online tax filers will need to provide a government identification document—such as a driver’s license, state ID, or passport—along with copies of bills, and, indeed, a selfie to verify their identity.

An IRS spokesperson confirmed with Gizmodo that tax filers will still be able to access basic information from the IRS website without logging into an ID.me account. However, in order to make and view payments, access tax records, and create payment plans—you know, important tax season things—you will need to create an ID.me account.

The IRS’s decision to deploy facial recognition technology, particularly technology developed by a private company, raises alarming questions. Problems with how facial recognition is developed and used are well documented. The technology has been shown to be less accurate when identifying darker-skinned, female faces. It has also misidentified and wrongfully arrested Black men. There are no federal laws governing the use of facial recognition. Still, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office, this technology has been used across the U.S. federal government, such as “to support criminal investigations related to civil unrest, riots, or protests” following the murder of George Floyd.

Given concerns about the ethics of facial recognition software, is this really the most accessible process for verifying tax filers’ identity? Can ID.me be trusted to store and maintain all this sensitive data? What are the future implications of government agencies using this kind of identity verification?

But first, let’s start with: What is ID.me?

The Virginia-based company launched in 2010. Over the course of the pandemic, it secured numerous contracts with federal agencies, including the Social Security Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as many state governments, primarily to verify unemployment benefits. In fact, as of July 2021, 27 states’ unemployment agencies use ID.me to verify unemployment benefit applications, despite the product’s reliance on access to a smartphone or computer and the Internet, which may be especially problematic for people who need unemployment dollars the most.

This swift and widespread adoption of ID.me’s identity verification services is likely the result of concerns about fraudulent claims for state and federal benefits at a time when the U.S. Department of Labor and state agencies were overwhelmed by millions of new unemployment claims. In June 2021, ID.me co-founder and CEO Blake Hall told Axios that his company uncovered a $400 billion theft of pandemic unemployment payments orchestrated by cybercriminal gangs from China, Nigeria, Russia, and elsewhere.

That figure has raised eyebrows. The Department of Labor and the Office of Inspector General estimate that a nationwide total of roughly $90 billion in unemployment benefits may have been lost to fraudulent payments.

Still, in spite of how suspect Hall’s $400 billion claim sounds, it achieved two things. First, it fed paranoia about spending that caused states to impose barriers that frequently flagged innocent claims as fraudulent and froze proper payments for millions of people. Second, it positioned ID.me as a leader in a market it helped to manufacture. Perhaps big claims are necessary to satisfy the company’s investors: ID.me was valued at $1.5 billion when it raised money from investors last year.

ID.me’s rapid expansion into the government contract space is emblematic of facial recognition technology’s relentless growth across the United States. It is also yet another example of how this controversial technology dug its roots deeper into our day-to-day lives during the pandemic and will likely remain an indefinite part of our routines, even if the implications are little understood.

It’s unclear if the executives deploying these technologies really understand them, either. Broadly speaking, facial recognition can be characterized as either “one-to-one” or “one-to-many.” Facial verification, for instance, is typically a one-to-one facial recognition process akin to unlocking your smartphone with your face. In contrast, a one-to-many approach compares a single face image to a trove of images in order to identify potential matches. Clearview AI is perhaps the most (in)famous example of a one-to-many facial recognition software. In a statement delivered on January 24, 2022, Hall shared that “Our 1:1 face match is comparable to taking a selfie to unlock a smartphone. ID.me does not use 1:many facial recognition, which is more complex and problematic.” Two days later, Hall posted on LinkedIn that ID.me does in fact use a one-to-many check on selfies used to sign into a user’s IRS account. More specifically, the ID.me software not only compares your selfie to the government ID you provided during account setup but also compares your selfie to an elusive, internal blocklist of alleged fraudsters and cybercriminals.

A privacy and civil liberty impact assessment conducted by the IRS confirms that the ID.me software has the capability to “identify, locate, and monitor individuals or groups of people.” Furthermore, while it makes sense for a government agency like the IRS to retain records for potential audits or investigations, as a “federally certified identity provider,” ID.me is required to store tax filers’ photo and government IDs for a minimum of seven years.

The proliferation of facial verification in government agencies is not an isolated incident. It has serious implications about how companies like ID.me can become government’s “digital gatekeepers.” Given the attention voter suppression issues have received, could you imagine ID.me being used to restrict voter registration or augment strict voter ID laws? What are the implications for undocumented tax filers? What about trans tax filers who use IDs that do not match their preferred name or gender presentation?

Unfortunately, the IRS contract with ID.me continues the trend of government agencies outsourcing questionable technology practices to private companies that make lofty claims that sound like they are in the public interest, even when their real incentive is profit. In early January, ID.me began circulating a white paper defending its facial recognition software and publicizing a “No Identity Left Behind” initiative. “As the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the transition to digital and the rapid at-scale adoption of evolving technologies, questions emerged about equitable access to government benefits and services,” the paper starts. To ID.me’s credit, this is an astute observation. But it’s simply not the problem ID.me is designed to solve.

Authors