U.S. “Stop the Steal” Messages Reverberate to Brazil, and Back

Adi Cohen, Benjamin T. Decker / Oct 27, 2022Benjamin T. Decker is founder and CEO and Adi Cohen is COO of Memetica, a digital investigations firm.

Political analysts and researchers are paying close attention to the second round in the Brazilian elections, which is expected to be a close race between incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro and former President Lula da Silva. While the results of the October 30 contest will surely have an impact on global politics, in an environment with high levels of uncertainty a challenge to the legitimacy of the results could have detrimental consequences in Brazil. But those consequences may also extend to other countries, including the US, where midterm elections will be held a week later.

Despite efforts to curb the spread of false rumors and misinformation, they are still prevalent in Brazil’s information environment. One novel contributing factor we have observed closely in our research is the strengthening of ties between Bolsonaro and his Brazilian supporters with political allies in the US. As has become evident over these past months, this relationship is not based just on a mutual ideological affiliation. Instead, US based “alt-tech” platforms provide Bolsonaro and his supporters in Brazil the opportunity to spread misinformation and propaganda intended to erode trust in the election system in the country while circumventing moderation by mainstream social media platforms, such as Facebook, and by Brazilian authorities. And increasingly, content that originates in Brazil is incorporated back into the effort by right wing actors in the U.S. to discredit the American election system.

Bolsonaro Exploits Alternative Platforms

Bolsonaro, who political analysts fear may try to incite a coup if he fails to win enough votes to maintain power, has a hybrid social media strategy that involves a presence on both mainstream platforms like Facebook and Instagram alongside less moderated platforms like Telegram. Over the past two years, the Brazilian Electoral Court has repeatedly ordered him to take down Facebook and Instagram posts flagged as election-related disinformation. But the smaller, right-wing platforms like Gettr and Truth Social do not officially cooperate with the Electoral Court.

Hours after the first round of Brazil’s election results were called, former US President Trump asked supporters to “Give Truth Social a lot of credit for the incredible win for President Jair Bolsonaro.” In typical fashion, Trump credited Bolsonaro’s performance on election day (he didn’t win outright, but did exceed expectations) to the video endorsement Trump posted on the platform he partially owns, just hours before Brazilian polls were open. While it is hard to assess what impact, if any, this endorsement had on voters, the video was shared by Bolsonaro and his allies during the day, and viewed by millions on social media. On Facebook it was one of the most viewed videos in Brazil that day, proving Truth Social is still a mechanism for Trump’s messages to achieve virality.

Perhaps that is one reason why over the past year, Bolsonaro promoted his fringe platform accounts over 500 times on Facebook and Instagram to his 36.4M followers. While still minute in comparison to those major platforms, Gettr is relatively popular in Brazil compared to other U.S. based fringe platforms such as Truth Social or Gab, and its CEO, former Trump advisor, Jason Miller, has visited the country to promote the platform as recently as September 2022. During the visit, Miller acknowledged Brazil is the second largest market for his platform, after the U.S. And election misinformation appears to be thriving there. Gustavo Gayer, an online influencer and Bolsonaro supporter who became an elected official, has been calling on his followers to open Gettr accounts, where speech is not “censored.” Eduardo Bolsonaro, a politician and the President's son, posted screenshots of his posts on Gettr to his Facebook account.

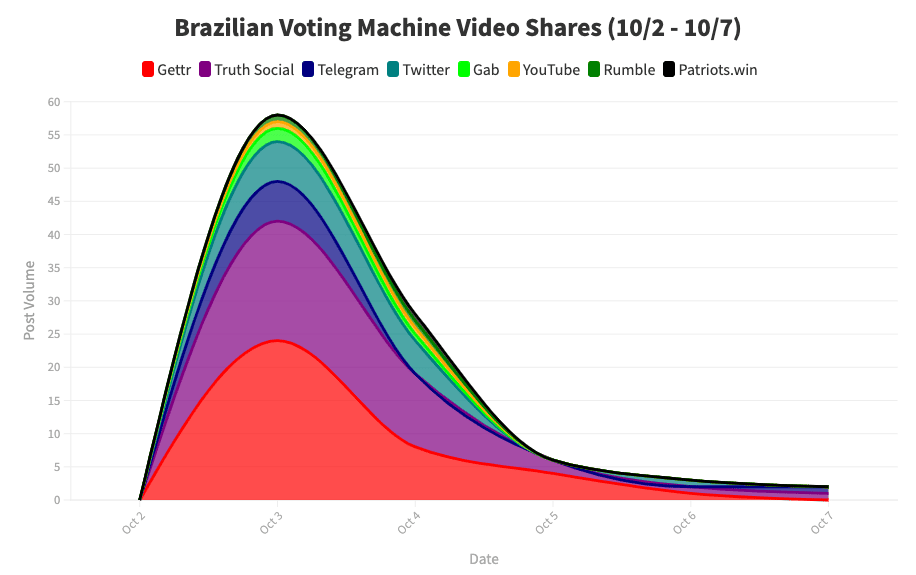

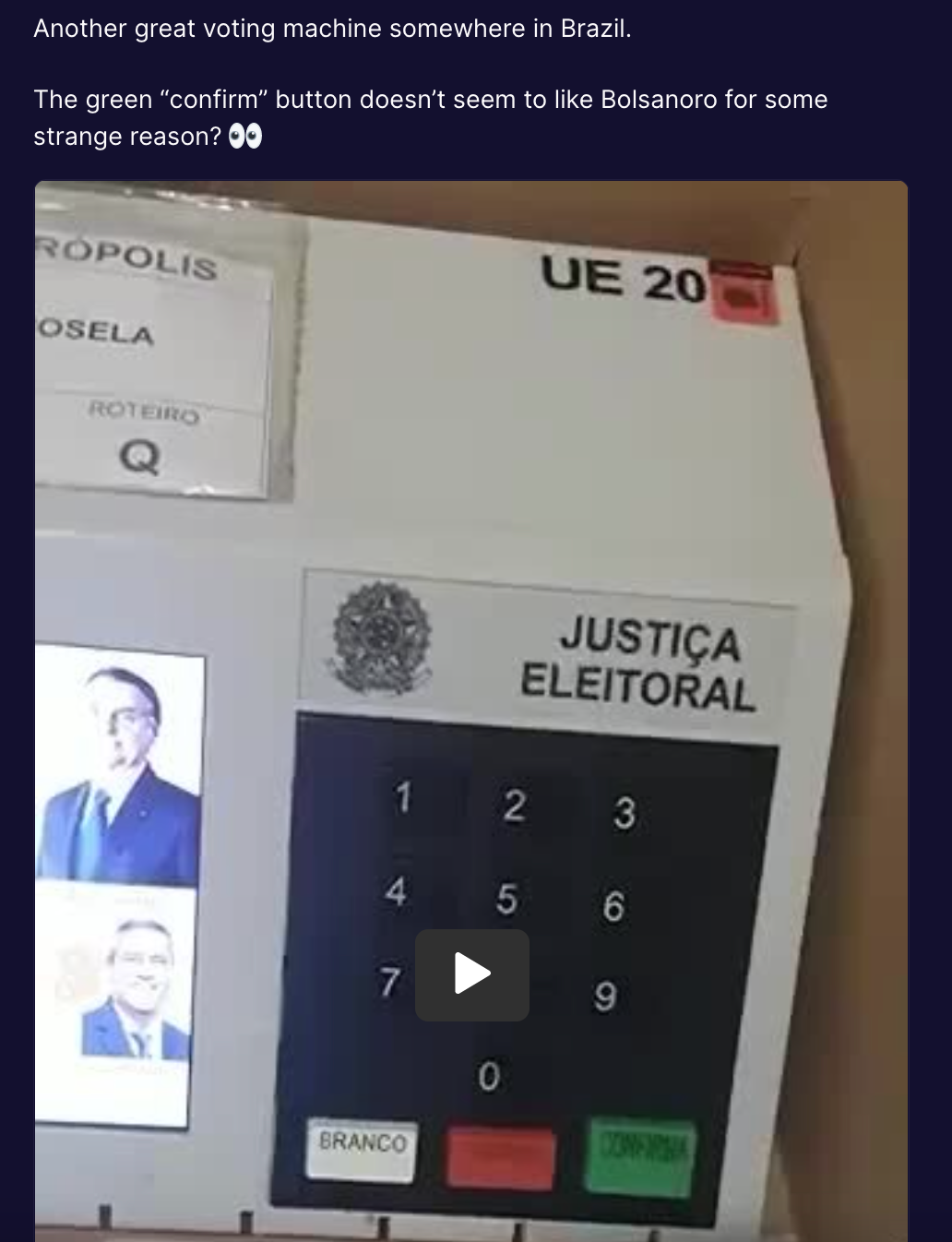

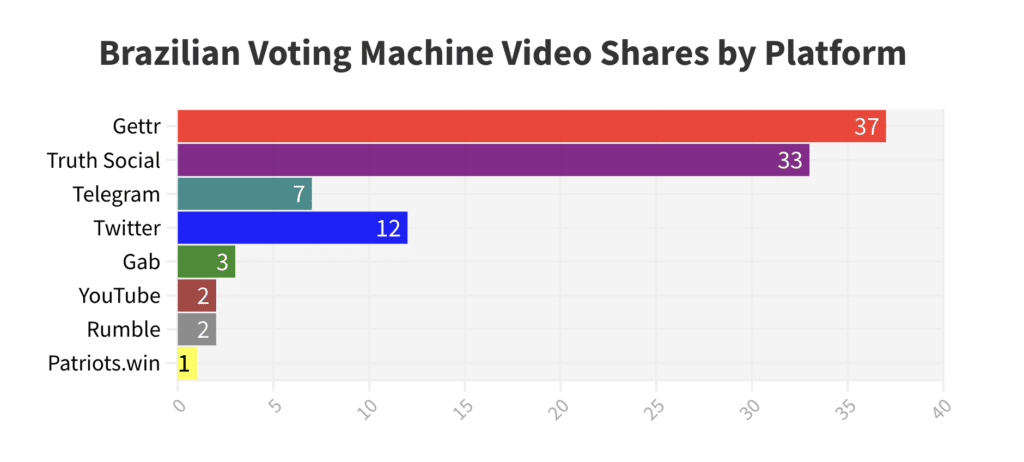

In the immediate aftermath of the first round of voting in the Brazilian presidential elections on October 2, a coordinated copypasta campaign emerged on fringe social media platforms, primarily on Gettr and Truth Social, seeking to sow doubt about Brazil’s electronic voting machines. A heavily-edited and decontextualized video purports to show a voting machine preventing an individual from voting for Bolsonaro. At last count, the video had been shared nearly 100 times across at least 8 platforms, and viewed at least hundreds of thousands of times in the following week.

While the posts came in several languages, including Portuguese, French, Spanish, and English, the majority of the video shares came from a myriad of American election conspiracy theorists already active on Gettr and Truth Social. Many of the posts featured identical text, such as: “Another great voting machine somewhere in Brazil…..The green “confirm” button doesn’t seem to like Bolsanoro for some strange reason? 👀(sic)”

Stop the Steal Activists in the U.S. Latch On

The circulation of the video appears to have been boosted by its adoption into the multi-pronged campaign led by U.S. election conspiracy theorists like MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell– a major proponent of Stop the Steal conspiracies – against the use of electronic voting machines. Since the 2020 election, American election conspiracy theorists have promoted a myriad of claims targeting electronic voting machine companies, including Dominion, Smartmatic and others. Following the first round in the Brazilian election, Eduardo Bolsonaro took to “Lindell TV” to warn Trump supporters that they should “watch closely” the elections in Brazil, “to prevent things that could happen in your elections.” Meanwhile, Steve Bannon claimed on his podcast that for “the globalists” on the left, Bolsonaro is an even bigger threat than Trump.

There are some signs that false claims about voting machines in Brazil may feed back into the U.S., serving as further “proof” that election systems are untrustworthy. While Bolsonaro’s performance during the first round of voting exceeded expectations, accounts and communities based in the US and Europe still circulated the videos originating in Brazil that rehashed Smartmatic and Dominion conspiracy theories from the 2020 U.S. election cycle, possibly in a bid to corroborate their false claims.

Any “evidence” will do. Far from deflated by their losses in court, U.S. Stop the Steal activists have been emboldened by a single incident they believe serves to justify their case. Lately, these activists who built a social media presence pushing false claims about the 2020 US election have celebrated the Los Angeles District Attorney’s (LADA) announcement about the investigation into and arrest of the CEO of an IT company that was contracted for poll workers management - Konnech - over the potential mishandling of data. The investigation came after a months-long campaign on social media that alleged Konnech has ties to the CCP. Though it was explicitly noted by LADA that the “the alleged conduct had no impact on the tabulation of votes and did not alter election results,” the mere existence of the investigation is considered by election truthers as validation for a range of false claims.

Such false claims are already taking a toll on the integrity of U.S. elections, specifically on the level of local voting administration: county executives across the country are facing violent threats, contending with confused and angry constituents with a range of demands driven by suspicion of voting machines and the software that runs them. Now, the influencers who continue to stoke the flames of Stop the Steal have set their sights on Brazil, where they have found a new political champion.

Disinformation Purveyors Act Local, Think Global

Whether the Brazilian election will produce the sort of chaos the U.S. suffered on January 6, 2021 remains to be seen. But if there is violence, it will be in part because of similar dynamics. And, the “evidence” of electoral fraud produced in Brazil may yet be re-used by conspiracy theorists in the U.S., as false claims born there are recycled for another cycle here, nurtured on right-wing platforms that are even less moderated than Facebook or Twitter.

This case highlights the challenge of contending with global nature of political disinformation. Without more robust and comprehensive multistakeholder policies and practices in place, the same playbook is likely to be adopted in a range of elections taking place over the next 12 months, particularly in areas where moderation is often lagging behind, such as in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, India, and Thailand. “Stop the Steal” may yet metastasize to other countries as it reverberates from Brazil and back to the U.S.

Authors