Two AI Transparency Concerns that Governments Should Align On

Tommaso Giardini, Nora Fischer, Johannes Fritz / Jul 22, 2024

Yasmin Dwiputri & Data Hazards Project / Better Images of AI / Managing Data Hazards / CC-BY 4.0

As regulation on AI transparency emerges, governments should seize the opportunity for international alignment on two shared concerns. First, interactions with AI may become indistinguishable from human interactions, potentially confusing users. Second, AI systems are inherently opaque. The Digital Policy Alert’s comprehensive report and tracker on global AI rules show that, despite these shared concerns, national rules on AI transparency diverge. Below, we outline divergent regulatory approaches and explain why governments must align to prevent hurdles to AI development and AI transparency.

Despite shared concerns, national rules on AI transparency vary

AI raises two fundamental transparency concerns that have gained in salience with the spread of generative AI. First, the interaction with AI systems increasingly resembles human interaction. AI is gradually developing the capability of mimicking human output, as evidenced by the flurry of AI-generated content that bears similarities to human-generated content. The “resemblance concern” is thus that humans are left guessing: Is an AI system in use? Second, AI systems are inherently opaque. Humans who interact with AI systems are often in the dark about the factors and processes underlying AI outcomes. The “opacity concern” is thus that humans are left wondering: How does the AI system work?

Governments are already addressing these shared concerns in national regulation and international alignment. Our comparative analysis of 11 AI rulebooks found that 25 percent of regulatory requirements proposed in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and South Korea pursue transparency. In China and the European Union (EU), the share of requirements devoted to transparency is 15 percent, while the share drops to under 10 percent in the United States (US). On the international level, the OECD AI Principles, endorsed by 47 governments, include a principle on transparency and explainability, where AI actors should commit to transparency and responsible disclosure regarding their AI systems. Specifically, they should provide meaningful information to foster a general understanding of AI, inform stakeholders of their interactions with AI, and provide information on the factors behind AI output.

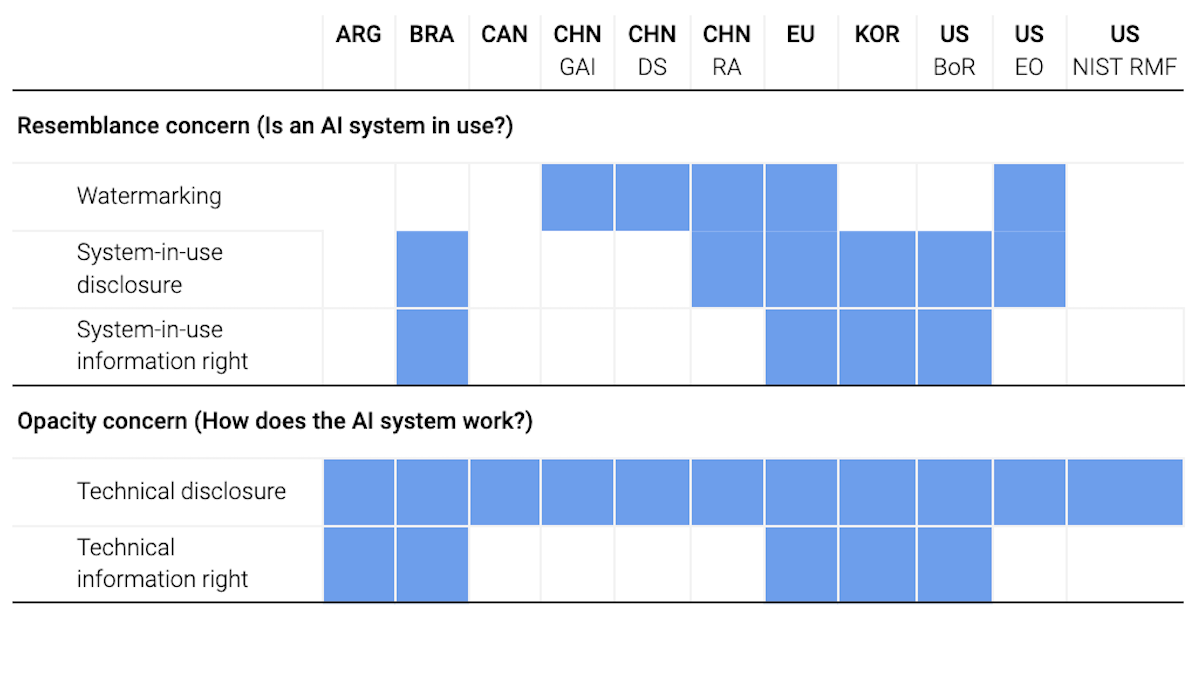

While the OECD AI principles provide a common framework for AI transparency, governments have created their own regulatory requirements. The most common regulatory requirements are content watermarking, public disclosure, and information rights:

- Watermarking requirements require AI providers to add a visible label or disclaimer on AI-generated output. They address the resemblance concern.

- Public disclosure requirements oblige AI actors to actively provide information, either on the use of AI systems or on the AI systems’ functioning. They address the resemblance and the opacity concern, respectively.

- Information rights empower users to request information on AI systems, which AI providers must reactively deliver. Information rights also extend to information on the use of AI systems or on the AI systems’ functioning. They address the resemblance and the opacity concern, respectively.

The heatmap below visualizes which AI rulebooks include transparency requirements, grouped by the concern the requirements address. Note that we analyze rulebooks that differ in their legal nature and current status. In Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and South Korea, we analyze proposed AI legislation. In China, we analyze the regulations that have been implemented on generative AI (“GAI”), deep synthesis services (“DS”), and recommendation algorithms (“RA”). In the United States, we analyze the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights (“BoR”), the Executive Order on AI (“EO”), and the NIST Risk Management Framework (“NIST RMF”), which are all adopted but do not directly establish binding obligations for firms. For the EU, we focus on the AI Act, which was published in the official journal in July 2024 and will be implemented over the coming years. Below, we outline granular differences between these requirements and discuss the consequences thereof.

Comparison of transparency measures in AI rulebooks

Transparency requirements on the use of AI

Watermarking requirements are prevalent in China’s regulations on deep synthesis services, generative AI, and recommendation algorithms, as well as the EU AI Act and the US Executive Order on AI. A fundamental difference between these requirements is their bindingness: China and the EU establish binding obligations, while the US Executive Order tasks the Secretary of Commerce and the Office of Management and Budget to draft a report and guidance covering watermarking. Other differences are more granular. China generally requires providers to incorporate watermarking without impeding users' ability to see the content. Stricter requirements on the visibility and location of watermarks apply to content that may lead to confusion or misrecognition by the public. The EU AI Act, on the other hand, requires providers of AI systems that generate synthetic audio, image, video, or text content to mark the output in a machine-readable format and make it detectable as artificially generated. The watermarking must be effective, interoperable, robust, and reliable. In addition, deployers of AI systems that generate either “deep fakes” or text published to inform the public on matters of public interest must disclose that the content was artificially generated or manipulated.

Public disclosure of the use of AI systems is required in Brazil, China, the EU, South Korea, and the US Executive Order on AI and Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. These requirements differ primarily regarding the AI systems they address. China applies this requirement to recommendation algorithms, Brazil to AI systems that interact with natural persons, and South Korea to high-risk AI systems. The EU mandates such disclosure for high-risk AI systems and any other AI system that interacts with natural persons. Finally, the US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights applies to all automated systems – on a voluntary basis – while the US Executive Order demands disclosure of AI use by government agencies. More subtle differences concern the format of disclosure. China, South Korea, and the US demand a basic notice. Brazil specifically regulates the design of human-machine interfaces. The EU allows for various formats of system-in-use disclosure.

The right to be informed that an AI system is in use is established in Brazil, the EU, South Korea, and the US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. These rights are often not specified and differ in terms of their scope and foreseen exceptions. Brazil establishes this right for all people affected by AI systems. The US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights declares that users should be informed of the use of automated systems. South Korea’s right only applies to users of services or products that involve high-risk AI processing. The EU provides this right regarding AI systems that directly interact with humans. The EU is also the only jurisdiction that provides exceptions, such as criminal investigations and circumstances where it is evident that the user is interacting with AI.

Transparency requirements on how AI functions

Technical disclosure requirements, demanding public information on the functioning of AI systems, are required in all 11 rulebooks we analyzed: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China (generative AI, deep synthesis, recommendation algorithms), EU, South Korea, and the US (Executive Order, NIST AI Risk Management Framework, Blueprint for AI Bill of Rights) all demand some form of technical disclosure. However, these requirements vary in scope, level of detail, and format among the jurisdictions. For example, while Brazil requires technical disclosure for all AI systems, the level of detail of the disclosure is limited, and no specific format is mandated. In contrast, jurisdictions such as the EU require disclosure only for high-risk AI systems and general-purpose AI models but provide precise disclosure obligations, listing the types of technical information to be disclosed and mandating disclosure in a public registry.

The right to specific information about the functioning of AI systems is established by Argentina, Brazil, the EU, South Korea, and the US Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. These requirements differ primarily in their scope and detail. Argentina, Brazil, and the US Bill of Rights cover all AI systems, while South Korea and the EU afford this right only to persons affected by high-risk AI systems. Regarding the level of detail, Brazil precisely elaborates the elements of information that users are empowered to receive, including the role of AI and humans in decision-making; the data, criteria, procedures, and factors that underlie decisions; and measures to ensure non-discrimination and reliability. South Korea, on the other hand, provides the most details regarding the procedure for requesting information.

International alignment can advance AI development and AI transparency

Regulatory divergence on AI transparency can fragment the global AI market, as we have studied in other digital policy areas. Complying with different requirements in each market is costly, especially for small firms. Going further, AI firms may consider compliance with certain regulatory requirements to be infeasible. This might cause firms not to enter a market or not to launch their full suite of AI products in a market. Finally, some firms may unknowingly deploy non-compliant AI systems, exposing them to enforcement risk.

Divergent AI transparency regulation can also exacerbate AI transparency concerns. Our analysis reveals that transparency requirements apply to specific types of AI systems and output, such as high-risk AI systems or deep fakes. However, users are rarely aware of these kinds of legal requirements. Rules that apply only in special contexts, which are not straightforward for the public to distinguish, can create a false sense of security. Humans will get accustomed to transparency regarding the specific AI systems regulated by their governments, but a lack of consistency may jeopardize their ability to detect the use of AI in contexts where transparency is not mandated. Without an easily understandable logic to signal where transparency requirements apply, divergent transparency expectations will emerge. Since each country applies transparency requirements to different AI systems, users will become increasingly unable to identify AI interactions – despite widespread international alignment on this concern.

Regulatory divergence presents a unique opportunity for governments to learn from each other. Governments can draw from the expertise accumulated by national regulators and other governments that are experimenting to find effective AI rules. For example, governments looking to establish information rights can learn from Brazil’s precise elaboration of information to be disclosed, South Korea’s detailed procedure for requesting information, and the EU’s unique exception mechanisms.

Still, international alignment is urgent because the dynamism of AI regulation will inevitably fade. Firms will look to large markets to identify models for compliance. As the attention of firms and governments turns to the approaches of China, the EU, and the US, the space for other governments to propose new solutions is lessened. To avoid the consolidation of a fragmented regulatory landscape, such as in data governance, governments must act now to advance new approaches and pursue international alignment.

Studying and comparing different approaches to operationalizing the OECD AI Principles is a chance for rapid learning. To enable such learning, the Digital Policy Alert’s comprehensive report on AI rules provides:

- A common language for AI rule makers: We code the text of AI rulebooks across the globe using a single taxonomy, tackling terminological differences.

- Detail for international alignment: We translate the five OECD AI Principles into 74 regulatory requirements and analyze interoperability with unique precision.

- Clarity on current AI rules: We systematically compare the world’s 11 most advanced AI rulebooks from seven jurisdictions.

- Transparency for AI rule makers: We make all our findings accessible through our CLaiRK suite of tools to navigate, compare, and interact with AI rules.

By leveraging these tools, policymakers can pursue detailed international alignment and develop interoperable AI rules. This alignment is crucial not only for reducing market fragmentation and compliance burdens but also for ensuring consistent and effective AI regulation.

Authors