Twitter Chaos Reinforces Why Governments Must Limit Reliance on Commercial Software

Keith Porcaro / Dec 21, 2022Keith Porcaro directs the Digital Governance Design Studio at Duke Law School, and serves on the board of Zebras Unite.

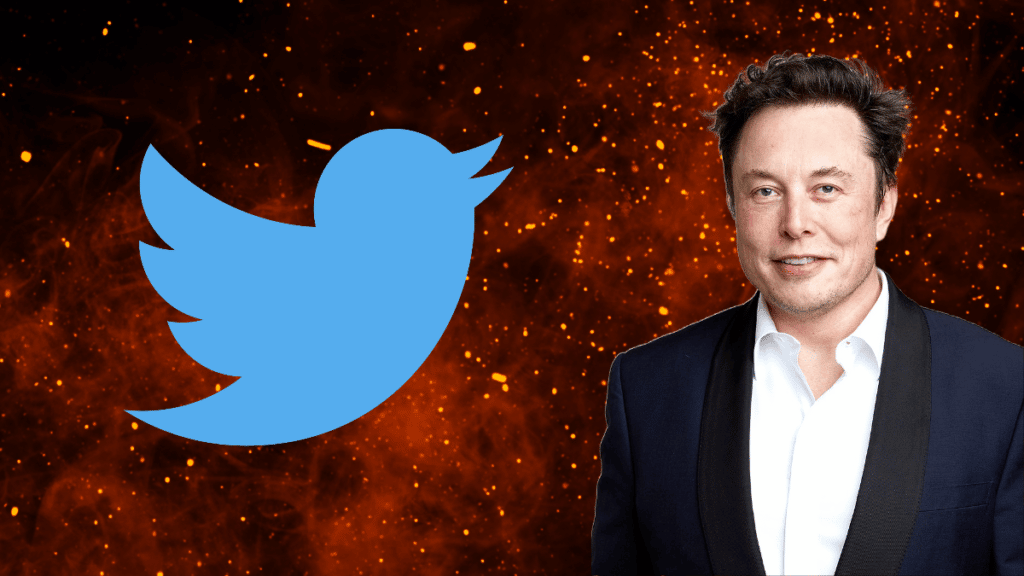

Twitter burns. You know the story by now. Paid checkmarks and banned accounts are in. Advertisers and staff are out. We're all learning what a toot is.

But as communities migrate, brands flinch, and policymakers fret, the most important lesson from Twitter's implosion may not be about Twitter at all. Civil society, government, and every other organization that relies on technology to deliver on some public mission should be asking, right now: what other parts of our tech infrastructure could end up like Twitter?

Consider a vignette.

Leading up to the 2020 U.S. elections, local election officials relied on Twitter to rapidly respond to misinformation. County clerks and local election offices were verified as official accounts. Twitter dedicated resources to fighting automated accounts, misinformation, and other election-related shenanigans. Twitter wasn't the only tool in the toolkit, but it was a useful one, especially for rapidly promoting accurate election information.

Cut to today. Account verification is available for $8/month. Impersonators are rampant. In the next election cycle, it seems obvious to worry about paid, verified accounts impersonating election officials.

It’s part of a worrying trend. Spam accounts have flooded Twitter topics related to protests in China. The company is struggling to keep up, in part because all of the staff responsible for mitigating these sorts of attacks were fired or resigned. Hate speech is on the rise, too, according to new research. Sudden policy changes, shadowbans, and account suspensions are the new normal, along with just-as-sudden reversals.

Dealing with the whims of a platform owner is perhaps the cost of engaging with social media. But this isn’t a one-off problem. As software– free or purchased– plays a more central role in the delivery of public services, the decisions of a company can have a far-reaching impact on how public services are delivered.

Take something less flashy, like case management software. What started as a simple way for a court or a hospital to digitize paper files has grown to take on an outsize role in how people receive access to justice, or healthcare. In your doctor's office, a commercial patient records system is keeping track of your appointments, prescriptions, health conditions, and communications with your doctors. In state and local courts across the country, court management systems are assigning jurors, storing case filings, sending reminders, and collecting fines and fees. There’s a decent chance these systems are purchased–just three electronic medical records companies control nearly 75% of the market. Tyler Technology’s Odyssey court management system is installed in the state or local courts for one-third of the U.S. population.

When these types of tools go wrong, people get hurt. A botched installation of a court management system in Alameda County led to faulty arrest warrants being issued—and people being wrongly arrested. An algorithm to predict sepsis based on data from a patient records systems launched with accuracy problems and ineffective alerts.

From traffic lights to benefits to prisons, government services teem with digital middlemen. And govtech as a field continues to boom, and consolidate. But the root problem isn’t that software is almost inevitably glitchy, or that predictive algorithms are almost inevitably discriminatory. It’s that public services increasingly involve the collection, management, and reuse of digital data. In many cases, public services can't be performed without it. And when critical public services depend on purchased digital infrastructure, governments begin to lose control of how services are delivered. Twitter’s hardcore transformation is but the latest reminder that promises about technology–about how data will be used and about how software will be maintained–are brittle. Business models change, companies get bought or go under, products lose support. And more often than not, users are left holding the bag.

The solution is simple, but not easy: organizations and agencies that depend on digital infrastructure must take ownership over it–literally.

Over the last decade or so, governments that can afford it have invested money in building homegrown digital services and tools. That’s a good start, but not every state or local jurisdiction can afford to go it alone–or should. The next step is to make it easier for governments across jurisdictions to collaborate on technology development–and co-own the results.

There are smart legal tools to help facilitate these collaborative arrangements that don’t involve a thicket of MoUs. What could that look like? How could, say, a group of local courts pool their resources to build a court-owned case management system?

One way to do it is with a trust, a legal tool for owning property on behalf of someone else. Trusts can be vehicles for pooled resources–they start with people or organizations that contribute property (code, money, etc.) to the trust. Here, participating courts might contribute software tools they’ve already developed; perhaps a rich state or even the federal government contributes a fork of their case management software.

Once it’s in a trust, the software would be managed by a trustee– perhaps a non-profit organization with technical expertise, or even a for-profit vendor. But here’s the trick. Unlike in a traditional vendor relationship, the trustee doesn’t actually own the software, nor are they allowed to unduly profit from it. Instead, the software (or other trust property) is managed exclusively for the benefit of the trust’s beneficiaries–participating courts. And, if something happens to the trustee, the software doesn’t get taken down with it: instead, a new trustee steps in.

Sit with it long enough, and you might think this example resembles an organization or company, but organized to benefit government agencies instead of shareholders. A trust isn’t the secret key to unlocking good government technology: from membership organizations to co-development agreements, there are no end of legal tools to ensure that software is collaboratively owned and well-maintained. But a trust helps to illustrate and execute a simple principle: that government software should be built for the people, not rented to them.

Co-ownership doesn’t make software less risky, or limit its potential for harm. But issues are easier to spot and correct when they aren’t hidden behind a vendor’s proprietary black box or buried in a roadmap. And most importantly, co-ownership helps ensure that the software that drives public services will continue to be accountable to the public, instead of an investor’s bottom line.

Even now, there are small moves that local governments and civil society can make to take control of their digital futures. Better procurement rules and processes, like bake-offs, can give agencies more control over the technology they must purchase. Better data governance policies help organizations account for technology's increasingly central role in service delivery. And better hiring strategies can help build internal technical capacity, and integrate that capacity with their service teams. Even just the simple process of coming up with exit plans for current and prospective technology tools can help organizations identify and mitigate future risk. For example, good exit planning might lead state or local governments to set up their own Mastodon instances (toot.gov?) to act as official local information services, instead of encouraging agencies to start accounts on privately-run servers.

But in the long term, there are only two outcomes for infrastructure: it's co-owned by the people who depend on it, or it’s co-opted by people who want to exploit that dependency. There is no third way.

It’s not clear what Twitter’s future holds. A better ownership structure or more attentive management still might not have changed its fate. But if Twitter was ever public infrastructure, it became so by accident. The digital infrastructure we create to deliver public services, to manage our courts, to deliver healthcare, to run our cities, isn’t built by accident. And it’s too important to leave to the whims of whoever might seek to exploit it next.

Authors