Transcript: US House Hearing on “Advances in Deepfake Technology"

Gabby Miller / Nov 9, 2023Gabby Miller is Staff Writer for Tech Policy Press.

On Wednesday, the US House of Representatives Oversight Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and Government Innovation held a hearing on the risks and challenges posed by “Advances in Deepfake Technology.”

The session was chaired by Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC), who opened the discussion emphasizing the dual nature of AI as both a tool for innovation and a potential weapon for harm, highlighting its use in creating highly realistic, synthetic images and video. Rep. Mace pointed out the distribution of AI-generated pornographic images and the exploitation of children, citing a letter from the attorneys general of 54 states and territories urging action against AI's use in generating child sexual abuse material (CSAM).

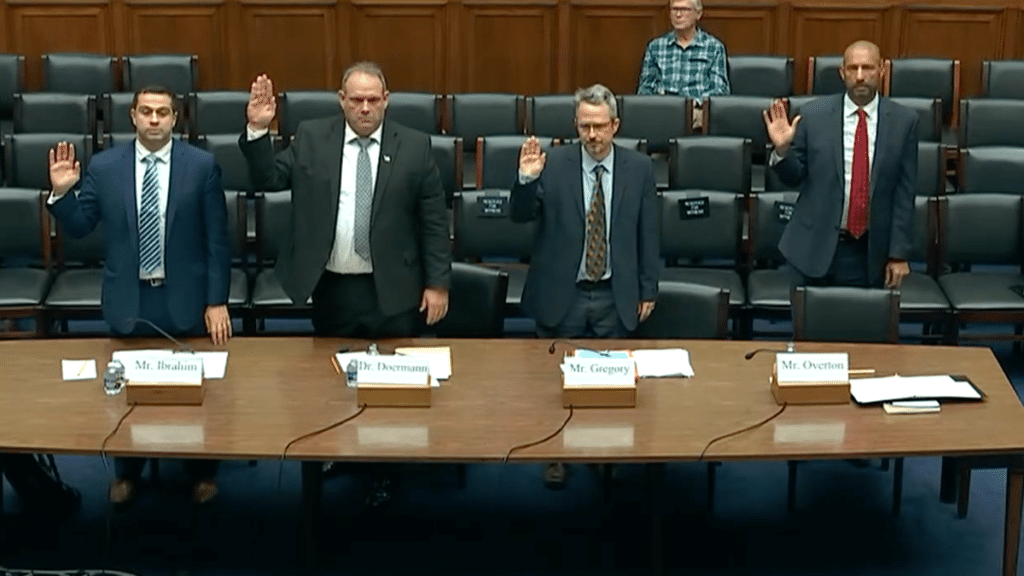

Witnesses included:

- Dr. David Doermann, Interim Chair, Computer Science and Engineering, State University of New York at Buffalo (written statement)

- Sam Gregory, Executive Director, WITNESS (written statement)

- Mounir Ibrahim, Vice President of Public Affairs and Impact, Truepic (written statement)

- Spencer Overton, Professor of Law, George Washington University School of Law (written statement)

Witnesses testified about the dangers deepfakes pose, especially their role in non-consensual pornography, cyberbullying, and misinformation. There was a consensus on the urgent need for both public awareness and legislative action to combat the misuse of deepfake technology, with suggestions for incorporating digital literacy into education and developing technologies to detect and mark AI-generated content.

Professor Overton focused on how women, people of color, and religious minorities bear the highest burdens as deepfake technology becomes more ubiquitous. This is particularly acute when it comes to women, especially those in public life, who are disproportionately targeted in deepfake pornography. Only one percent of deepfake pornography features men, and the total number of deepfake porn videos has increased 464 percent within the last year, according to his testimony. (More than 415,000 pornographic deepfake images were uploaded to the top 10 websites for sharing such content this year alone, according to industry analyst Genevieve Oh.) Overton also mentioned the ways in which deepfakes are fueling racial distrust and facilitating foreign interference and voter suppression in US elections.

In his opening remarks, Overton cited the experience of researcher and former DHS official Nina Jankowicz, who specializes in combatting state-sponsored disinformation and online gendered abuse, and her experience as the subject of AI-generated videos falsely depicting her engaging in sex acts. “Although they may provide cheap thrills for the viewer, their deeper purpose is to humiliate, shame, and objectify women, especially women who have the temerity to speak out,” Jankowicz wrote in The Atlantic in June. “By simply existing as women in public life, we have all become targets, stripped of our accomplishments, our intellect, and our activism and reduced to sex objects for the pleasure of millions of anonymous eyes.”

A significant portion of the discussion was dedicated to the need for federal legislation to address the legal gaps in dealing with nonconsensual synthetic content. The proposed Preventing DeepFakes of Intimate Images Act, introduced in June by Rep. Joe Morelle (D-NY) was mentioned as a positive step; it would give a right of civil action and possible criminal penalties against those that create and distribute nonconsensual intimate imagery. The need for technology companies to collaborate and share information to combat deepfakes was stressed, as was the importance of continued federal research and investment to improve detection methods.

Dr. Doermann emphasized that while there is technology to detect deepfakes, it is not reliable enough to be the sole solution. Truepic’s Mounir Ibrahim discussed the prospect of new technology that would embed information about content provenance into synthetic media. Sam Gregory from WITNESS cautioned that “we should be wary of how any provenance approach can be misused for surveillance and stifling freedom of speech.”

Witnesses discussed the need for a comprehensive approach, including legislation, education, and further technological innovation. The hearing concluded with a call for action to address the challenges posed by deepfake technology, while also being mindful of protecting civil liberties and privacy.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the hearing.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Good afternoon everyone. The subcommittee on Cybersecurity Information Technology and Government Innovation will come to order. Welcome Without objection, the chair may declare a recess at any time. I recognize myself for the purpose of making an opening statement. Good afternoon and welcome to this hearing of the Subcommittee on Cybersecurity Information Technology and Government Innovation. The groundbreaking power of artificial intelligence is a double-edged word. There's nowhere more evident than an AI's capacity to generate realistic looking images, audio and video. The latest AI algorithms can be used to make synthetic creations nearly indistinguishable from actual faces, voices, and events. These creations are referred to as deepfakes. deepfakes can be put to a variety of productive uses. They're used to enhance video games and other forms of entertainment, and they're being used to advance medical research as well.

But deepfake technology can also be weaponized and cause great harm. It can be used to make people appear to say or do things that they have said or done. It can be used to perpetuate various crimes including financial fraud and intellectual property theft. It can also be used by anti-American actors to create national security threats, and these are not hypothetical, hypothetical harms. A few weeks ago, AI generated pornographic images of female students in a New Jersey High school were circulated by male classmates, a company that studies deepfakes found more than 90% of deepfake images are pornographic. Last month, the attorneys general of 54 states and territories wrote to congressional leaders urging they address how AI is being used to exploit children, specifically through the generation of child sexual abuse material or CSAM, pronounced CSAM. They wrote and I quote, AI can combine data from photographs of both abused and non-abuse children to animate new and realistic sexualized images of children who do not exist but may resemble actual children. Creating these images is easier than ever. The letter states as anyone can download the AI tools to their computer and create images by simply typing in a short description of what the user wants to see. Falsified videos and photos circulating on social media are also making it difficult to separate fact from fiction in conflicts taking place around the world.

Videos purportedly taken from the ground in Israel. Gaza and Ukraine have circulated rapidly around on social media only to be proven and authentic. One AI generated clip showed the president of Ukraine urging troops to put down their arms. I'm not interested in banning all synthetic images or videos that offend some people or make them feel uncomfortable, but if we can't separate truth from fiction, we can ensure our laws are enforced or that our national security is preserved and there's more insidious danger that the sheer volume of impersonations and false images we're exposed to on social media lead us to no longer recognize reality when it's staring us right in the face. Bad actors are rewarded when people think everything is fake. That's called the Liar's Dividend. The classic case of the Liar's dividend is the very real Hunter Biden laptop, which many in the media and elsewhere falsely attributed to Russian disinformation, but the risk from deepfakes can be mitigated. We'll hear about one such effort today being pursued by a partnership of tech companies interested in maintaining a flow of trusted content. Voluntary standards can enable creators to embed content providence data into an image or video, allowing others to know if the content is computer generated or has been manipulated in any way.

Our witnesses today will be able to discuss these standards along with other ideas for addressing the potential harms caused by deepfakes. With that, I would like to yield to the ranking member of the subcommittee, my friend, Mr. Connolly.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

Thank you, Madam Chairwoman. Thank you for having this hearing. Very timely. I'll begin by noting our disappointment on the minority side, yet again, the lack of a hearing on the scorecard for implementation of atar. This committee initiated that legislation, created that scorecard, has had 15 hearings, a record for Congress, and it's produced over 25 billion of savings. We believe strongly that we need to continue that oversight and continue to press the executive branch for progress. I would note that until now, that effort over the last seven years has been completely bipartisan. I have worked with my colleagues on the other side of the aisle, Mr. Meadows, Mr. Issa, Mr. Heis, Mr. Hurd, to make this happen, and we've always collaborated in a bipartisan way to make it happen. So I hope we can revisit that issue and continue to make progress and keep what I think is a very proud record by the subcommittee and by the full committee in the holding executive branch’s feet to the fire when it comes to modernization, updating cybersecurity, encryption, and moving to the cloud.

With that, with respect to this hearing, when most people hear the term deep fake, this image may jump to mind. While images like this, his holiness Pope Francis in a puffy coat seems innocuous. Most are, as the chairwoman just indicated, quite insidious. Take the AI generated image, for example, the Gaza image on screen.

Since the armed conflict between Israel and Hamas first broke out, false images created by generative technology have proliferated throughout the internet. As a result, these synthetic images have created and algorithmically driven fog of war, making it significantly more difficult to differentiate between truth and fiction. Just last year at the outset of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, a fabricated video of Ukrainian President Zelensky calling for Ukrainian soldiers to lay down their weapons, also referenced by the chairwoman, circulated on social media very widely it was a deepfake, but thanks to Ukraine's, quick response to Russian disinformation, it was quickly debunked. Welcome to the new frontier of disinformation. Few politics are one realm of deepfakes, but let's look at some numbers. According to one study, 96% of deepfake videos are of non-consensual pornography, 96%. Another report confirmed that deepfake pornography almost exclusively targets and harms young women. Knowing this, it should be no surprise that the very first deepfake ever created depict to the face of a famous female celebrity superimposed unto the body of an actor in a pornographic video.

These kinds of manipulated videos are already affecting students in our schools. In one instance, a group of high school students in New Jersey used the images of a dozen female classmates to make AI pornography. This is wrong. It threatens lives and self-esteem among young people, and it needs to be stopped. Earlier this year, ranking member Joe Morrell introduced a bill called the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act. The Bill bans non-consensual images. The order instructs the Secretary of Commerce, whoops, I'm sorry, of sharing synthetic intimate images and creates additional legal courses of action For those who are affected, I'm a co-sponsor to that legislation and urge all of my colleagues to join us in this important effort. Congress must not shy away from preventing harmful proliferation of deep fake pornography, but it's not just deep fake videos that we have to worry about. With ai, scammers have the ability to easily create audio that mimics a person's voice matching age, gender, and tone.

Thousands of Americans are scammed over the telephone every year using this very technology and deepfake capabilities further exacerbate the problem. So what can we do? AI image detecting tools are being developed and used to help verify the authenticity of machine generated images. Other tools place watermarks on AI generated media to indicate that the media is synthetically created. While these tools improve and evolve, both the public and the private sector must cooperate to educate the public on where these tools are and how to use them. Government and the private sector must collaboratively highlight the dangers and consequences of deepfakes and teach how to combat this misinformation and its abuse. Private developers must implement policies that preserve the integrity of truth and to provide transparency to users. That's why I joined the letter led by Representative Kilmer and the new Democratic Coalition AI Working group that requests leaders of prominent generative AI and social media platforms to provide information to Congress outlining efforts to monitor, identify, and disclose deceptive synthetic media content, and the public sector is already taking bold consequential steps toward collaboration and comprehensive solutions.

I applaud the efforts of the Biden administration to secure commitments from seven major or AI companies to help users identify when content is in fact AI generated and when it's not. The Biden administration took a resolute and unprecedented step last week when it issued its executive order on artificial intelligence. The sweeping executive order speaks directly to the issues we seek to examine today. It leans on tools like watermarking that can help people identify whether what they're looking at online is authentic as a governed document or tool of disinformation, the order instructs the Secretary of Commerce to work enterprise-wide to develop standards and best practices for detecting fake content and tracking the provenance of authentic information. I trust this subcommittee will conduct meaningful oversight of these efforts because we as a nation need to get this right. I'm proud that the administration has taken the first step in performing its role as a global leader in addressing generative technology.

I also look forward to hearing more today about existing and evolving private sector solutions and suggestions. We already know Congress must continue to fund essential research programs that support the development of more advanced and effective deepfake detection tools. Funding for research through DARPA and the National Science Foundation is critical. That requires a fully funded government. I once again urge all of my colleagues on this and the other side of the aisle to fulfill a constitutional duty and work to pass a bipartisan long-term funding agreement. I thank the chairwoman, Ms. Mace for holding this hearing and emphasizing the harm of deepfakes and disinformation and look forward to any legislative action that may follow this endeavor. I yield back.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you, Mr. Connolly. Today I am pleased to introduce our witnesses for today's hearing. Our first witness is Mounir Ibraham, executive vice president of public affairs and impact at Truepic. I would like to next introduce Mr. Langworthy to introduce the second witness.

Rep. Nick Langworthy (R-NY):

Thank you very much, Madam Chair. I'm pleased to have the opportunity to introduce our witness from Western New York. Dr. David Doermann is the interim chair of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He is also a professor of Empire Innovation and the director of the Artificial Intelligence Institute at ub. Prior to UB, Dr. Doermann was a program manager at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency or DARPA, where he developed and oversaw $150 million in research funding in the areas of computer vision, human language, and voice analytics technologies. Dr. Doermann is a leading researcher and innovative thinker in the areas of document image analysis and recognition. Welcome to the hearing, Dr. Doermann. We look forward to your testimony today and I yield back.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. Our third witness is Mr. Sam Gregory, executive Director of Witness, and our fourth witness today is Mr. Spencer Overton, professor of law at George Washington University School of Law.

Welcome everyone and we're pleased to have you here this afternoon pursuant to committee Rule nine G. The witnesses will please stand and raise your right hands. Do you solemnly swear or affirm that the testimony you're about to give is the truth, the whole truth, and not think but the truth, so help you God, let the record show the witnesses all answered in the affirmative. We appreciate all of you being here today and look forward to your testimony. Lemme remind the witnesses that we've read your written statements and they will appear in full in the hearing record. Please limit your oral statements to five minutes. As a reminder, please press the button on the microphone in front of you so that it is on and the members can hear you when you begin to speak. The light in front of you will turn green after four minutes, the light will turn yellow When the red light comes up, your five minutes has expired and we would ask that you please wrap it up. I would like to recognize Mr. Ibrahim to please begin his opening statement.

Mounir Ibrahim:

Thank you, Chairwoman Mace, ranking Member Connolly and members of this subcommittee for the opportunity to brief today. My name is Mounir Ibrahim, executive vice President for Truepic, a technology company that focuses on digital content, transparency and authenticity. Prior to my time at Truepic, I was a foreign service officer with the US Department of State. My time as a US diplomat was one of the greatest honors of my life and led me to my work. Today I was posted at the US Embassy in Damascus at the start of the Arab Spring. I saw protesters risk their lives being beaten and attacked in front of me as they attempted to document the violence with smartphones. It was there I saw the power of user-generated content later as an advisor to two different US permanent representatives to the United Nations. I saw similar images from conflict zones around the world enter into the UN Security Council, but regularly undermined by the country's critics and bad actors that wanted to undermine reality by simply claiming those images were fake today.

That strategy, as the Congresswoman noted, is referred to as the Liar's Dividend and it is highly effective. Simply claiming user-generated content is fake, in my opinion. In addition to the horrible non-consensual pornographic threat that we have from generative ai, the Liar's Dividend is one of the biggest challenges we have because we've digitized our entire existence, government business and people all rely on what we see and hear online to make decisions, we need transparency and authenticity in that content to make accurate decisions. There is no silver bullet to transparency or authenticity online, but there is growing consensus that adding transparency to digital content so that content consumers, the people who are seeing those images and videos, can tell what is authentic, what is edited or what is synthetic will help mitigate the challenges. A lot of this work is taking place by a coalition of organizations known as the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, C2PA, by which Truepic is a proud member.

The C2PA developed the world's first open standard for digital content provenance, which is often referred to as content credentials. The basic concept of provenance is attaching the fact or history of that image, that video, that audio that you are interacting with online to the file itself, so the content consumer is informed of the artifact associated with that like time date, how it was created, how it was edited, et cetera. The standard is interoperable, which is critical, so digital content can flow from one platform, one device to another, so as long as they align to the same standard. Truepic supports the C2PA because we believe interoperability is critical to help mitigate the challenges that you all laid out today. Our technology and our approach boils down into two areas. We help secure what is in fact authentic and captured from a smartphone, and we help add transparency to a synthetic or generative piece that is created from a platform.

From the authentic side, we created a technology called Secure Controlled Capture. It is used by hundreds of businesses every day ranging from Equifax to Ford Motor Company to add transparency into their operations. It's also been used in 150 countries. We've deployed this technology on the ground in Ukraine with Microsoft to help USAID partners document destruction to cultural heritage and national infrastructure. On the generative AI side, the C2PA standard has been recognized by the partnership for AI as one of the lead disclosure mechanisms for generative ai. We are also a proud supporter of the Partnership for AI and we strive to work towards this goal. In April, we worked with Nina Schick, an author, and Revel AI to launch the world's first transparent deepfake, so when you actually see the video, you see the content credentials and know it is in fact generated by AI. This past month we launched two other partnerships with hugging Face to democratize these tools to add content credentials so anyone can use them on their open source models and with Qualcomm the chipset manufacturer. We think that is a watershed innovation because generative AI is going to move to your smartphone, and this chip set has this transparency technology added to it. It's worth noting that it's not only true pick working on this Microsoft Adobe stability, AI have all either launched products or made commitments to add the same transparency. This is a growing ecosystem.

In closing, if possible, I'd like to offer some thoughts on how government might help mitigate these AI challenges with transparency and authenticity in mind. First, government has a unique platform and I applaud you for having this. Hearing events like this will raise awareness and help educate the public and give an opportunity to ask the right questions. Second, legislation can be powerful. We've seen in the National Defense Authorization Act, the bipartisan Deepfake Task Force Act in the recent executive order Section 4.5, all of which point to transparency and authenticity and digital content. We've also seen it abroad in the UK and the EU. Finally, government should consider how it can use content credentials to authenticate its own communications and prevent constituents from being deceived and also reap the same benefits that the private sector does in cost reductions, risk reductions and fraud reductions. Thank you for your time and I welcome any questions.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. I now recognize Mr. Doermann to please begin his opening statement.

David Doermann:

Chairwoman Mace, ranking member Connolly and Honorable members of Congress. I appreciate the opportunity to testify before you today on the pressing issue of deep take technology, creating and distributing computer generated image and voice cloning. In 2014, only a decade ago when DARPA began the media forensics program, commonly known as MediFor, the primary goal was to detect and characterize image manipulation at scale. This was consistent with DARPA's mission of preventing strategic surprise. Although we imagined a world where our adversaries would become better at manipulating images, few imagined the pace at which automated manipulation would develop and the impact that technology would have on our society as a whole. The introduction of generative adversarial networks or gans kicked off a plethora of tools that can generate images of people and objects that don't exist, synthesize speech that clones, voices of others implements realtime puppeteering to control talking heads, and as we hear most the ability to generate deepfake videos.

The surprise we missed perhaps is the automated tools that are becoming more accessible and user-friendly. They require a lot less data and a lot less technical expertise. Open source software can be downloaded today and run by any one of us on a commodity laptop. As these technologies advance at an unprecedented rate is crucial to recognize the potential for both positive and negative implications. We hear its use at both ends of the spectrum every week. This week we heard about AI being used to finish a new Beatles song and as we've heard from the ranking member and chairwoman that a group of students in a New Jersey high school used it to generate pornographic videos of their classmates. Despite the President's executive order, the testimony of our thought leaders and business leaders, we're not moving fast enough to curtail the continued damage this technology is doing and will do as it evolves.

Not only has it taken has been used for non-consensual pornography, cyber bullying and harassment causing great harm to individuals, but the potential for national security implications are grave deepfakes can be used to impersonate government officials, military personnel or law enforcement and in general lead to misinformation and potentially dangerous situations. Today, this is no longer a problem that can be solved by simply detecting and removing generated content from our social media and content provider sites. I urge you to consider legislation and regulation to address the misuse of deepfake technology as a whole. Striking the right balance between free speech and safeguards to protect against malicious uses of deepfakes is essential. First and foremost, public awareness and digital literacy programs are vital to helping individuals learn about the existence of deepfakes and how to ensure that they don't propagate this type of misinformation. It may seem obvious that people want to know what type of information is being generated and you would hope that they would be able to hold it upon themselves not to spread it, but we find that that's not the case.

We should consider including school media literacy education and promote critical thinking. Collaboration between congress and technology companies is essential and I'm glad to see that that's happening. To address the challenges posed by deepfakes, tech companies should be responsible for developing and implementing the policies to detect and mitigate this type of content, including what we were hearing today on their platforms and sharing most importantly what they learn with others. We've addressed this type of a problem with our cybersecurity and we should be doing that same thing with our misinformation. More robust privacy and consent laws are needed to protect individuals from using their likeness and voice and deepfake content without their permission and continued research and development in ai deepfake technology are necessary. As is funding for these counter deepfake misuse to counter deepfake misuse. We have created these problems, but I have no doubt that if we work together, we're smart enough to figure out how to solve them. I look forward to taking your questions.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. I now recognize Mr. Gregory to please begin his opening statement.

Sam Gregory:

Chairwoman Mace, ranking Member Connolly and members of this subcommittee, I'm Sam Gregory, executive director of the human rights organization Witness. Since 2018, Witness has led a global effort– Prepare, Don't Panic– to inclusively prepare for deepfake and related synthetic media and generative AI technologies. The capabilities and uses of deepfakes have often been over-hyped, but with recent shifts, the moment to address them more comprehensively has come.

First, I'll cover technological advances, commercialization and accessibility characterized changes in the last year. Deepfake technologies are now available and widely used consumer tools, not just niche apps. Furthermore, they're easy to use and particularly for audio and image can be instructed with plain language and require no coding skills. Realistic image generation has improved dramatically in its quality and customization in a year with widely available audio cloning tools. One minute of audio is enough to fake a voice. While video remains harder to do in complex real world scenarios, consumer apps can swap an individual's face onto another's body, strip the clothing from a woman's body, matching lip movements to a new audio track in a video is being demoed by Google and live deepfakes are feasible. As a result, we're seeing an increased volume and ease in creating variations of realistic synthetic photos, audio, and eventually video of specific real individuals and contexts. I would like to flag four future trends. These are increasing ease in instructing these tools in plain language. Two, more ability to tailor outputs, three more realistic outputs and four, eventually similar advances in video to what we now see in audio and images. Moving on to the risks and harms. deepfakes are causing harms in the US and globally with disproportionate impacts on groups already at risk of discrimination or vulnerable to offline harms. Women and girls are widely targeted with non-consensual sexual images, and this problem is escalating. AI generated sexual abuse material CSAM is increasing simulated audio scams are proliferating as are misuses of AI audio in political contexts.

My organization frequently sees claims of AI generation used to muddy the waters and dismiss critical real content while actors and others have their likenesses stolen to use in non satirical commercial contexts. Political processes are likely to be impacted by deep fakes and recent polls find the American public is fearful of their impact. However, it is unreasonable to suspect individuals to spot deceptive, yet realistic deep fake imagery and voices guidance to look for the six fingered hand or inspect visual errors in a pope in a puffer jacket does not help in the long run. Meanwhile, under-resourced newsrooms and community leaders across the political spectrum are under pressure and do not have access to reliable tools that can detect deep fakes. That is because deepfake detection efforts are not yet reliable at scale or across multiple different ways of creating deepfakes, nor are there widely shared methods to clearly indicate how AI was used in creating content.

This leads me to what Congress should consider to address these advances in technology and accompanying misuses. Firstly, enact federal legislation around existing harms including non-consensual sexual content and the growing use of generative AI in CSAM, incorporating broad consultation with groups working on these existing harms while safeguarding constitutional and human rights would help you craft appropriate steps. Secondly, since people will not be able to spot deepfake content with their eyes or ears, we need solutions to proactively add and show the provenance of AI content and if desired and under certain circumstances. Human generated content provenance such as the C2PA standard mentioned before means showing people how content and communications were made, edited and distributed, as well as other information that explains the recipe. The best choices here go beyond binary, yes, no labels. Overall, these transparency approaches provide a signal of AI usage, but they do not per se indicate deception and must be accompanied by public education.

Critically, these approaches should protect privacy and not collect by default personally identifiable information for content that is not AI generated. We should be wary of how any provenance approach can be misused for surveillance and stifling freedom of speech. My third recommendation is on detection alongside indicating how the content we consume was made. There is a continuing need for after the fact detection for content believed to be AI generated from witnesses, experience the skills and tools to detect AI generated media remain unavailable to the people who need them the most, including journalists, rights defenders and election officials domestically and globally. It remains critical to support federal research and investment in this area to improve detection overall and to close this gap, it should be noted that both provenance and detection are not as relevant to non-consensual sexual, where a real versus faces often beside the point. Since the harm is caused in other ways, we need other responses to that as a general and final statement for both detection and provenance, to be effective in helping the public to understand how deepfake technologies are used in the media we consume, we need a clear pipeline of responsibility that includes all the technology actors involved in the production of AI technologies more broadly from the foundation models to those designing and deploying software and apps to the platforms that disseminate content. Thank you for the opportunity to testify.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. I will now recognize Mr. Overton to begin your opening statement.

Spencer Overton:

Chairwoman Mace ranking Member Connolly subcommittee members, thanks for inviting me to testify. My name is Spencer Overton. I'm a professor at GW Law School and GW's Equity Institute. My research focuses on civil rights law, democracy, and disinformation. Now, while defect technologies offer many benefits, they also threaten democratic values and they produce harms disproportionately born by women and communities of color. Nina Janowitz, for example, she's a 34 year old researcher. She specializes in state-sponsored disinformation and gendered online abuse. Earlier this year, she found out she was featured in at least three synthetic videos that appear to show her engaging in sex acts. Now, she wrote about these videos she wrote, and I'll just use her words, although they may provide cheap thrills for the viewer, their deeper purpose is to humiliate shame and objectify women, especially women who have the temerity to speak out. Users can also easily find deepfake porn videos of the singer Taylor Swift, the actress Emma Watson and the former Fox News host, Megan Kelly, Democratic officials such as Kamala Harris, Nancy Pelosi, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and Republicans, Nikki Haley and Elise Stefanik, and countless other prominent women by simply existing as women in public life, we have all become targets stripped of our accomplishments, our intellect, and our activism, and reduced to sex objects for the pleasure of millions of anonymous eyes.

Deepfake pornography accounts for, as you all said, over 90% of all deepfake videos online, women are featured as the primary subjects of 99% of deepfake pornography. While men are the primary subjects and only 1% non-consensual deepfake pornography does not simply hurt women's feelings. It's an anti-democratic form of harassment designed to silence and undermine public confidence in women. As legitimate public policy leaders, deepfake technology is also fueling racial harassment. Earlier this year, a deepfake video showed a middle school principal saying that black students should be sent back to Africa, calling them monkeys and the N word and threatening gun violence. User-friendly and affordable deepfake technology could allow bad actors to be even more effective in dividing Americans and undermining democracy. So we think back to 2016, the Russians we know set up social media accounts pretending to be black Americans. They posted calls for racial justice, developed a following, and then just before election day, they targeted ads at black users, encouraging them to boycott the election and not vote.

Now today in this world, the Russians or domestic bad actors could spark social upheaval by creating deepfake videos of a white police officer shooting an unarmed black person. Indeed, earlier this year just before Chicago's mayoral election, a deepfake video went viral of a candidate casually suggesting that regular police killings of civilians was normal and that candidate lost. Now, the private sector is definitely important, but the market alone won't solve all of these problems. Initial studies, for example, show that deepfake detection systems have higher error rates for videos showing people of color. In conclusion, as deepfake technology becomes more common, women and communities of color bear increasing burdens. Members of Congress should come together, understand these emerging challenges, and really take action to protect all Americans and our democracy from the harms. Thank you.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. I would now like to recognize myself for five minutes for questioning, and my first question is for every member of the panel, so let's not do five minutes each because we only have five minutes today, so if you could just keep it brief. I'm very concerned about deepfake technology being weaponized against women and children. Mr. Overton, as you made your point, the overwhelming majority of deepfake circulating are pornographic. Most of these involve images of women. Some are images of children. As a woman in a public position and the mother of a teenage daughter, it's alarming to me how easy it's become to create realistic pornographic images of actual women and girls. These images can cause lifelong and lasting humiliation and harm to that woman or girl, so what can we do to protect women and children from being abused in this manner? Mr. Ibrahim, and we'll just go across the panel.

Mounir Ibrahim:

Thank you, Congresswoman. Indeed. This is as everyone noted, the main issue right now with generative ai and there are no immediate silver bullets, so several colleagues have noted media literacy and education and awareness.

Also, a lot of these non-consensual pornographic images are made from open source models. There are ways in which open source models can potentially leverage things like provenance and watermarking so that the outputs of those models will have those marks and law enforcement can better detect, better trace down and take down such images. Those are just some thoughts.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. Mr. Doermann.

David Doermann:

One of the challenges that we have is that we don't have a culture that a lot of these things are unacceptable. In the case of New Jersey, I understand that there were parents even that said, boys will be boys. These are not the kinds of things that we have today that should allow these types of things to progress. From a technology point of view, we do have the ability to do partial image search as another panelist here said, we have the original source material and we could check that something has been manipulated in that way. It just requires that we do it at scale. It's not an easy solution, but those are the types of things that we have to think outside the box.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Mr. Gregory.

Sam Gregory:

There's a patchwork of state laws at the moment. There is no federal law at the moment that would protect women and girls. We need to make it clearer where there is individual liability that can be applied here. I should also note that recent research indicates how easy it is to find these deep fakes on search engines. Just type in a name plus deepfakes and you'll come up with a deepfake of a public figure, so addressing the responsibility of platforms within to make sure that it's less easy to do that because at the moment it's very hard for individuals to chase down all the examples of their deepfakes online with individual requests.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Mr. Overton.

Spencer Overton:

The proposed Preventing deepfakes of Intimate Images act is a good start. Having both criminal and civil penalties is important. Not having overly burdensome intent requirements to establish a violation, and also focusing on both creators and distributors. Those are some important factors.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. My next question is about laws. Do we need changes in law, in law enforcement practice and there are revenge porn laws as an example, but doesn't cover deepfakes necessarily on the federal level 15 US Code Section 6851. I happen to be reading about it today, civil action related to intimate images in videos, but it relates to real images and videos, not to deepfakes, and so I see a huge gap in law and even law enforcement practice. And what are your thoughts on that? We have a minute, so everybody gets like 20 seconds.

David Doermann:

I would encourage examination of laws and what generative AI platforms and models can do to pre-mark their content outputs so that we can better effectively take things down and track them. I think, I'm not a legal scholar, but it's my understanding that the same way as our first generative algorithms targeted very high level individuals, it might not be just pornographic. It might be just showing somebody in another type of compromising situation. We need comprehensive laws to address these things.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Mr. Gregory.

Sam Gregory:

Extending federal law to cover synthetic content that fulfills the same purpose as revenge porn and making sure it's accessible globally. We encounter cases of this all over the world.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you, Mr. Overton.

Spencer Overton:

Yes, I concur with Mr. Gregory.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

That was easy. Alright, thank you. And I'll yield for five minutes to my colleague, Mr. Connolly.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

Thank you men and chairwoman. It seems to me that this is not as simple as it seems. Let's take AI for pornography. So if somebody is a caricaturist and uses AI and they want to make fun of a political figure and they make him to be the emperor with no clothes crown on the head and he's walking around with no clothes to make the point that he's empty, he's without merit or politically lost. Now that's not pornography. It is AI generative technology. It is not the real thing, but within the perimeters of the law, being a public official, you've got to put up with a fair amount. On the other hand, if somebody took that same individual and used it clearly as not a caricature, not fun, but in a pornographic AI, generative technology, has he crossed a line in terms of the law, professor Overton?

Spencer Overton:

So I think the answer is yes. Obviously we've got to be very sensitive in terms of these first amendment issues including satire and parody, that type of thing. I would say though that even if we have disclosure in terms of deepfakes, this targeting of women who are political figures, even if it's satire, I think that it is a problem and something that we really need to hone in on.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

I agree with you, but you're the professor of law, not me. Surely you appreciate the delicacy of that. However, under our constitutional system,

Spencer Overton:

Correct.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

We have limits for public officials to be able to seek redress in terms of libel.

Spencer Overton:

That's right.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

You can defame us…

Spencer Overton:

New York Times versus Sullivan.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

Yes, you can defame us in a way you cannot defame some other citizen. So we have high standards for public officials, so I put that as a category of complexity, not so simple in terms of regulating.

Spencer Overton:

It's something we've got to grapple with. I really refer you to Mary Anne Franks, my colleague at GW did a great law review article in 2019 where she really chronicled these harms as not really contributing to free speech and the marketplace of ideas in truth, and so there's something else that's here and we've got to really grapple.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

Right? I agree with you. I don't think it's as simple as we would all like. Now, that's public officials, private individuals such as the girls we talked about in New Jersey are pure victims of somebody else's perverse sense of fun or pleasure and they suffer real harm legally. What's their protection? What's their redress right now?

Spencer Overton:

Yeah, right now, the problem is a lot of law does not cover this. In some states have laws with regard to deepfakes, but many states do not. And existing, even though almost all states have revenge porn laws, this activity does not clearly fall under that. So often there is no recourse.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

So we could maybe use the sort of underage piece of law to get at this if these victims are under a certain age.

Spencer Overton:

I think that that's correct, but even the CSAM issue that we talked about before isn't always clearly covered here in terms of existing laws with regard to child pornography. So we've got some real holes in the law.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

Yep. Okay. Well, I think that's really worthy of an explanation not only by us up here, but by your profession and by the academic community. Dr. Doermann, let's send you back in time. You're back at DARPA and you're in charge of all AI research and projects. What are we not doing that you want to see funded? Pick two or three that we really ought to be doing right now because it could have a beneficial effect if we plow this ground in terms of its promise in protecting ourselves from Deeplake.

David Doermann:

Absolutely. It is not just deepfakes. You're right. It's AI in general. We have gotten to the point where these language models, where these models that we have are completely unexplainable. People believe that AI is somehow an answer and everything is always right that comes out of these systems. We can't converse with these systems and they can't explain why they made a decision or how they made things. I think the explainability issues, and these are things that DARPA is looking at now, but we need to have the trust and the safety aspects explored at the grassroots level for all of these things.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-VA):

I just say, Madam Chair, my time is up, but I think there's a huge difference between the Pope in a puffery jacket, which doesn't do much harm, and the example of Ukraine where deepfakes has him saying, we're putting down our arms and surrendering that can cause or end a conflict in an undesirable way. And so clearly protecting ourselves and being able to counter that disinformation in a very expeditious way, if not preventing it to begin with, I think is kind of the goal. I thank you.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you, Mr. Connolly. I now recognize Mr. Timmons for five minutes.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Thank you, Madam Chair. It seems we have two main issues here. One is attribution. A lot of people would see a deep fake video and not know whether it was fake or real, and the next issue is updating our legal structures to address the core purpose of them. We have revenge porn laws in many states. The update to the Violence Against Women Act that Chairwoman Mace just mentioned gives a civil cause of action for $150,000. The purpose of that was to address this issue, and the legislative intent did not really keep in mind the possibility of a deep fake. If you can't distinguish it, there's no difference. So I guess my first question, Dr. Doermann, is there any way that we can, one mandate identification to show that it is an altered image or a fake image, and then two, is there a way to mandate that in the code, just like a photo on my iPhone says where it is and the GPS location that was taken, could you do the same thing with an IP address and a location and a time and a date stamp on the video and mandate that and make it illegal to create images that using this technology without the attribution component?

Does my question make sense?

David Doermann:

Yeah, I think you actually have two parts there. Well, first of all, if you mandate creating content or creating things that require you to disclose, for example, that it's a deep fake, the adversaries and the people that are doing these bad things in the first place, they're not going to follow those rules anyway. I mean, that's a much lower bar than actually creating pornographic.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Well, we got to take the first step of US citizens within our jurisdiction.

David Doermann:

We can, yes.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

We could easily say if you create this, there's a civil penalty that's available, and then if you do this, there's a criminal penalty just like states have done with revenge porn.

David Doermann:

Again, there's also a continuum between the things that it's used for good and the things that it's used for bad. So just saying that you're going to identify it...

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

We could literally use AI to say whether something is considered porn or not, and then whether that is...

David Doermann:

I'm not sure about that. I think we see a continuum of these.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

You're going to have to take a photo of somebody initially of their face, of their likeness to then give the AI the ability to create something that is resembling the original human, and you could then create...

David Doermann:

Well, the face is, but the original content can come from a legal pornographic film, for example, and that's what's happening,

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

But you're putting someone's face on it that isn't the same face to make it look like them in an attempt to do the same thing that we have revenge porn laws to do.

David Doermann:

That's what these, my colleagues here are saying that there are holes in these laws that don't necessarily allow you to do that.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Mr. Overton, is there any argument that you could use the existing statute to file a federal lawsuit against somebody for sharing a deep fake?

Spencer Overton:

There is an argument. I think the question is does it hold water?

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

We got some judges in this country that didn't do just about anything, right?

Spencer Overton:

But we want certainly some consistency in enforcement of law.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Sure. We could also maybe expand the code section too, but I guess then it becomes the whole purpose of revenge point laws is theoretically you were complicit in the initial video, but not complicit in the sharing, and it has to be done for retribution of some kind. So I guess it becomes a lot more complicated when you're talking about celebrities and whatnot, but they also deserve the same degree of privacy and respect that we're seeking for everyone else. So I guess, okay, let's go back.

Spencer Overton:

Lemme just follow up here. Disclosure under the court is much more acceptable than complete restrictions here. So let me just put that in terms of the first amendment.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Okay, and I guess Dr. Doermann, back to the attribution issue. I mean, it is not unreasonable to try to create a legal framework through which a photo that is taken on my iPhone has all of this metadata. I mean, theoretically, if that metadata is not present in a video, then we would know that it is a malicious.

David Doermann:

Yeah. Yes, in theory, yes. The problem comes again with enforcing this because you now have forcing individuals to mark their content. It is an issue...

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Could we use AI to seek out and automatically delete information videos that don't have the ...

David Doermann:

Absolutely. And you could forge this type of stuff as well. Even camera fingerprints. These things can be forged, so we just have to be careful about what we rely on, and we make sure that everybody is playing by the same rules and being able to enforce those types of things.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Theoretically, we could mandate certain websites to use AI to identify deepfakes and automatically delete them if they are deemed pornographic. Theoretically.

David Doermann:

Theoretically.

Rep. Willliam Timmons (R-SC):

Okay. Alright. Sorry, madam Chair. Thank you. I yield back.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Yeild back. Nope, thank you. I will now recognize Mr. Burchett for five minutes.

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Thank you, chair lady. Several questions. I'm just going to ramble if it's all right with y'all. This is a question to all of y'all, and I'd like to discuss how criminals are using this deepfake technology to produce child sex abuse material, just child porn, and when these criminals use this deepfake technology to make this material of children rather than alter the images that already exist, how can law enforcement agencies determine the age of the subject in the material?

Mounir Ibrahim:

Yes, sir. We have seen a rising amount of cases. The New Jersey one was noted. There was also a recent case in Spain in which these models were used for underage young girls in terms of how can law enforcement potentially use that information and detect, there is some growing thinking that if the models themselves add some watermark or provenance to everything,

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Explain to me what the watermark, what is that? I know what it means in something, but explain.

Mounir Ibrahim:

It would be an invisible algorithm that is attached to every image that is spit out of the generator, whether it is a benign or malicious image in which could be decoded by a law enforcement agency or has some sort of chain of custody that could potentially be useful. That is something that a variety of organizations are looking at over.

David Doermann:

We also have to educate our legal system on how to use these things. I was on a panel at aaas s about a month ago, and very simple things such as the use of face recognition as an AI tool, which we know has been controversial to say the least. So we just have to make sure that our content providers are service providers, are on board, and that they're sharing this type of information with each other, and that's definitely something that's doable.

Sam Gregory:

The problem this is creating in CSAM has similarities to other problems. It's a volume problem where you then have a triage problem for the people who have to do the investigation because of creating synthesized images and adapting existing images. So investing in tools that are available to law enforcement as well as others who have to do that triage work would be a critical next step.

Spencer Overton:

I just would know these evidentiary issues are very challenging for law enforcement.

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Yeah, I think the court cases are that if they just generate like a fake face that they can't be held for child porn. Is that correct?

David Doermann:

My understanding that those laws are changing, but the laws, the previous laws, again, I'm not a legal scholar, required a victim, and that was really the loophole there, but they are closing those.

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Okay, well, how can we prevent this technology from being used to create child sex abuse material? Mr. Overton, we'll start with you first, brother. Yeah, I think that legislation is very important in terms of that directly deals with the CSAM issue.

Mounir Ibrahim:

I'll agree with Mr. Overton. It's legislation around CSAM. There's clear reasons to legislate and include this alongside nonsynthetic images.

David Doermann:

And I'll just emphasize from the technology point of view. This is a genie that's out of the bottle. We're not going to put it back in. These types of technologies are out there. They could use it on adults, consenting adults the same way, and it's going to be difficult to legislate those, but the technology is there. It's on the laptops of anyone that wants to download it from the internet. And so the legislation part is the best approach.

Mounir Ibrahim:

I echo my colleagues and I would just note the majority of these materials are often done through open source models, so the more models you can get, sign up to frameworks and guardrails, pushing bad actors into other models that are harder to use would be beneficial.

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Do y'all agree that these AI generated images of children, real or not, should be illegal?

Mounir Ibrahim:

I do.

David Doermann:

Absolutely.

Sam Gregory:

Yes.

Spencer Overton:

Yes. We assume they're not hurting children. They are, yes.

Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN):

Yeah. I'm always amazed when people say, I sponsored some legislation in Tennessee where actually people abused children given the death penalty, and I was in, my statement was that they'd given these kids a lifetime sentence and there's no coming back from that. It's a lifetime of guilt, and you see a lot of the kids self-inflict wounds and take their own lives, and it's just brutal. So anyway, thank You'all chair lady.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Yes, thank you. I'll now recognize Mr. Burlison for five minutes.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

Thank. Begin with Mr. Doermann. Can we talk about the technology that is possibly available to recognize or identify AI and how that might be applied in a commercial setting?

David Doermann:

Well, the biggest challenge of any of these technologies is the scale. Even if you have an algorithm that works at 99.9%, the amount of data that we have at scale that run through our major service providers makes the false alarm rates almost prohibitive. We need to have a business model that our service providers, our content providers have that makes them want to take these things down if they get clicks. That's what's selling ads now. And if it's not illegal, if we can't hold them responsible in any way, it makes it very difficult to convince them to do anything.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

Given the currently today, there's the ability to identify graphic content, violent content, and then to often block it or require a person to take some action to basically break the glass and go through and see that content. Can that not be applied to deepfake images or things that are created with That way the individual would at least know that there's no truth to this image?

David Doermann:

Absolutely. I mean, but the places that this content is showing up are on those pay sites or on sites where it's mixed in with other type of content. So just detecting it is not necessarily the issue

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

And they don't have a self-interest, financial interest in identifying the deepfake?

David Doermann:

Correct.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

Okay. I understand what you're saying. So let me ask, but the technology is capable. We just need to identify

David Doermann:

Not necessarily the deepfake part. If you do a reverse image search, for example, in a number of different sites, you can do it for the entire image. But if you take just the face of an individual, that's what we really need. We need to be able to say, okay, we're not going to look at the entire video because this video isn't real. Right? It wasn't. Well, part of it is real. The video part of the nude body is real and the faces is generated. So if we could identify those people, make sure that we have that consent before it gets spread, that might be one thing, but just to detect something is being pornographic. We're still not detecting the fact that it was generated with a deepfake.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

You're saying that there is technology, AI that can view videos and images and ascertain whether it's a deepfake

David Doermann:

Not reliably enough.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

There currently isn't anything.

David Doermann:

This is 80, 85% maybe, and every time we release a tool that detects this, our adversaries can use AI to cover up that trace evidence. So no, that's why I said in my opening statement that detection and trying to pull this stuff down is no longer a solution. We need to have a much bigger solution.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

Mr. Gregory, how do we authenticate the content without creating a surveillance state or suppressing free expression?

Sam Gregory:

The first thing I would say is as we're looking at authenticity and provenance measures, ways that you can show how something was made with AI and perhaps with human inputs. And I think we should recognize that the future of media production is complex. It won't just be a yes or no of ai. It'll be yes, AI was used here. No AI wasn't. Here's a human. So it's really important that we actually focus this on the how media was made, not the who, right? So you should know, for example, that a piece of media was made with an AI tool was altered perhaps to change an element of it, and that might be the critical information rather than a political satirist made this piece of media, which certainly would not be something we'd want to see here in the US and globally when you look at how that could be misused. So I think we're entering something where we're a complicated scenario, where it is both the authenticity tools and also detection tools, my experience of a very messy reality where we need to focus on both, but we've got to do it with civil liberties and privacy at heart.

Rep. Eric Burlison (R-MO):

As I understand it, there's, and this is a question for Mr. Ibrahim, what is the difference between detecting deepfakes and content authentication?

Mounir Ibrahim:

Detecting deepfakes would be something you do after the fact. It would be a system that would look at a video and try to spit out a binary or a results-based response, content authentication or provenance does while it's being created. That's what tropic does. So as the image is being captured from a phone or a smartphone or a piece of hardware, you are attaching cryptographically hashing the time, the date, the location, et cetera, into the media file while it's being created. So it's a proactive measure versus a reactive measure.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC):

Thank you. I want to thank all of our witnesses for being here today. In closing, I want to thank you for your testimony again. So with that and without objection, all members will have five legislative days within which to submit materials and to submit additional written questions for the witnesses, which will be forwarded to the witnesses for their response. So if there's no further business without objection, the subcommittee stands adjourned.

Authors