Transcript: Senate Judiciary Subcommittee Hearing on Oversight of AI

Justin Hendrix / May 16, 2023

Today the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law hosted a hearing titled "Oversight of A.I.: Rules for Artificial Intelligence."

Witnesses included:

- Samuel Altman, CEO, OpenAI

- Christina Montgomery, Chief Privacy & Trust Officer, IBM

- Gary Marcus, Professor Emeritus, New York University

What follows is a rush transcript. Check the video of the hearing to confirm quotes.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Now for some introductory remarks.

“Too often we have seen what happens when technology outpaces regulation, the unbridled exploitation of personal data, the proliferation of disinformation, and the deepening of societal inequalities. We have seen how algorithmic biases can perpetuate discrimination and prejudice, and how the lack of transparency can undermine public trust. This is not the future we want.”

If you were listening from home, you might have thought that voice was mine and the words from me, but in fact, that voice was not mine. The words were not mine. And the audio was an AI voice cloning software trained on my floor speeches. The remarks were written by ChatGPT when it was asked how I would open this hearing. And you heard just now the result I asked ChatGPT, why did you pick those themes and that content? And it answered. And I'm quoting, Blumenthal has a strong record in advocating for consumer protection and civil rights. He has been vocal about issues such as data privacy and the potential for discrimination in algorithmic decision making. Therefore, the statement emphasizes these aspects.

Mr. Altman, I appreciate ChatGPT's endorsement. In all seriousness, this apparent reasoning is pretty impressive. I am sure that we'll look back in a decade and view ChatGPT and GPT-4 like we do the first cell phone, those big clunky things that we used to carry around. But we recognize that we are on the verge, really, of a new era. The audio and my playing, it may strike you as curious or humorous, but what reverberated in my mind was what if I had asked it? And what if it had provided an endorsement of Ukraine, surrendering or Vladimir Putin's leadership? That would've been really frightening. And the prospect is more than a little scary to use the word, Mr. Altman, you have used yourself, and I think you have been very constructive in calling attention to the pitfalls as well as the promise.

And that's the reason why we wanted you to be here today. And we thank you and our other witnesses for joining us for several months. Now, the public has been fascinated with GPT, dally and other AI tools. These examples like the homework done by ChatGPT or the articles and op-eds, that it can write feel like novelties. But the underlying advancement of this era are more than just research experiments. They are no longer fantasies of science fiction. They are real and present the promises of curing cancer or developing new understandings of physics and biology or modeling climate and weather. All very encouraging and hopeful. But we also know the potential harms and we've seen them already weaponized disinformation, housing discrimination, harassment of women and impersonation, fraud, voice cloning deep fakes. These are the potential risks despite the other rewards. And for me, perhaps the biggest nightmare is the looming new industrial revolution. The displacement of millions of workers, the loss of huge numbers of jobs, the need to prepare for this new industrial revolution in skill training and relocation that may be required. And already industry leaders are calling attention to those challenges.

To quote ChatGPT, this is not necessarily the future that we want. We need to maximize the good over the bad. Congress has a choice. Now. We had the same choice when we face social media. We failed to seize that moment. The result is predators on the internet, toxic content exploiting children, creating dangers for them. And Senator Blackburn and I and others like Senator Durbin on the Judiciary Committee are trying to deal with it in the Kids Online Safety Act. But Congress failed to meet the moment on social media. Now we have the obligation to do it on AI before the threats and the risks become real. Sensible safeguards are not in opposition to innovation. Accountability is not a burden far from it. They are the foundation of how we can move ahead while protecting public trust. They are how we can lead the world in technology and science, but also in promoting our democratic values.

Otherwise, in the absence of that trust, I think we may well lose both. These are sophisticated technologies, but there are basic expectations common in our law. We can start with transparency. AI companies ought to be required to test their systems, disclose known risks, and allow independent researcher access. We can establish scorecards and nutrition labels to encourage competition based on safety and trustworthiness, limitations on use. There are places where the risk of AI is so extreme that we ought to restrict or even ban their use, especially when it comes to commercial invasions of privacy for profit and decisions that affect people's livelihoods. And of course, accountability, reliability. When AI companies and their clients cause harm, they should be held liable. We should not repeat our past mistakes, for example, Section 230, forcing companies to think ahead and be responsible for the ramifications of their business decisions can be the most powerful tool of all. Garbage in, garbage out. The principle still applies. We ought to beware of the garbage, whether it's going into these platforms or coming out of them.

And the ideas that we develop in this hearing, I think will provide a solid path forward. I look forward to discussing them with you today. And I will just finish on this note. The AI industry doesn't have to wait for Congress. I hope their ideas and feedback from this discussion and from the industry and voluntary action, such as we've seen lacking in many social media platforms, and the consequences have been huge. So I'm hoping that we will elevate rather than have a race to the bottom. And I think these hearings will be an important part of this conversation. This one is only the first, the Ranking Member and I have agreed there should be more. And we're going to invite other industry leaders. Some have committed to come, experts, academics, and the public we hope will participate. And with that, I will turn to the Ranking Member. Senator Hawley.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Thank you very much Mr. Chairman. Thanks to the witnesses for being here. I appreciate that several of you had long journeys to make in order to be here. I appreciate you taking the time. I look forward to your testimony. I want to thank Senator Blumenthal for convening this hearing, for being a leader on this topic. You know, a year ago we couldn't have had this hearing because the technology that we're talking about had not burst into public consciousness. That gives us a sense, I think, of just how rapidly this technology that we're talking about today is changing and evolving and transforming our world. Right before our very eyes, I was talking with someone just last night, a researcher in the field of psychiatry who was pointing out to me that the ChatGPT and generative AI, these large language models, it's really like the invention of the internet in scale, at least, and potentially far, far more significant than that. We could be looking at one of the most significant technological innovations in human history.

And I think my question is, what kind of an innovation is it going to be? Is it gonna be like the printing press that diffused knowledge, power, and learning widely across the landscape that empowered, ordinary, everyday individuals that led to greater flourishing, that led above all two greater liberty? Or is it gonna be more like the atom bomb, huge technological breakthrough, but the consequences severe, terrible, continue to haunt us to this day? I don't know the answer to that question. I don't think any of us in the room know the answer to that question. Cause I think the answer has not yet been written. And to a certain extent, it's up to us here and to us as the American people to write the answer.

What kind of technology will this be? How will we use it to better our lives? How will we use it to actually harness the power of technological innovation for the good of the American people, for the liberty of the American people, not for the power of the few? You know, I was reminded of the psychologist and writer Carl Jung, who said at the beginning of the last century that our ability for technological innovation, our capacity for technological revolution, had far outpaced our ethical and moral ability to apply and harness the technology we developed. That was a century ago. I think the story of the 20th century largely bore him out. And I just wonder, what will we say as we look back at this moment about these new technologies, about generative ai, about these language models and about the hosts of other AI capacities that are even right now underdeveloped, but not just in this country, but in China, at the countries of our adversaries and all around the world. I mean, I think the question that young pose is really the question that faces us, will we strike that balance between technological innovation and our ethical and moral responsibility to humanity, to liberty, to the freedom of this country? And I hope that today's hearing will take us a step closer to that answer. Thank you, Mr. Chairman. Thanks.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thanks, Senator Hawley, I'm gonna turn to the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee and the Ranking Member, Senator Graham, if they have opening remarks as well.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

Yes, Mr. Chairman, thank you very much. And Senator Hawley as well. Last week in this committee, full committee, Senate Judiciary Committee, we dealt with an issue that had been waiting for attention for almost two decades. And that is what to do with social media when it comes to the abuse of children. We had four bills initially that were considered by this committee and what may be history in the making. We passed all four bills with unanimous roll calls, unanimous roll calls. I can't remember another time when we've done that. And an issue that important it's an indication I think, of the important position of this committee in the national debate on issues that affect every single family and affect our future in a profound way.

1989 was a historic watershed year in America because that's when Seinfeld arrived and we had a sitcom, which was supposedly about little or nothing, which turned out to be enduring. I like to watch it, obviously, and I'm always marvel when they show the phones that he used in 1989. And I think about those in comparison to what we carry around in our pockets today. It's a dramatic change. And I guess the question is, I look at that is does this change in phone technology that we've witnessed through the sitcom really exemplify a profound change in America? Still unanswered. But the basic question we face is whether or not this issue of AI is a quantitative change in technology or a qualitative change. The suggestions that I've heard from experts in the field suggest it's qualitative. Is that AI fundamentally different? Is it a game changer? Is it so disruptive that we need to treat it differently than other forms of innovation? That's the starting point. And the second starting point is one that's humbling and that is effect when you look at the record of Congress and dealing with innovation, technology and rapid change.

We're not designed for that. In fact, the Senate was not created for that purpose. But just the opposite, slow things down. Take a harder look at it. Don't react to public sentiment. Make sure you're doing the right thing. Well, I've heard of the potential, the positive potential of AI, and it is enormous. You can go through lists of the deployment of technology that would say that an idea you can sketch on an, a website for a website on a napkin can generate functioning code. Pharmaceutical companies could use the technology to identify new candidates to treat disease. The list goes on and on. And then of course, the danger. And it's profound as well. So I'm glad that this hearing is taking place, and I think it's important for all of us to participate. I'm glad that it's a bipartisan approach. We're going to have to scramble to keep up with the pace of innovation in terms of our government public response to it. But this is a great start. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thanks. Thanks, Senator Durbin, it is very much a bipartisan approach, very deeply and broadly bipartisan. And in that spirit, I'm gonna turn to my friend Senator Graham.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC)):

In the spirit of hear from him. Thank you both.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you. That was not written by AI for sure. <Laugh>.

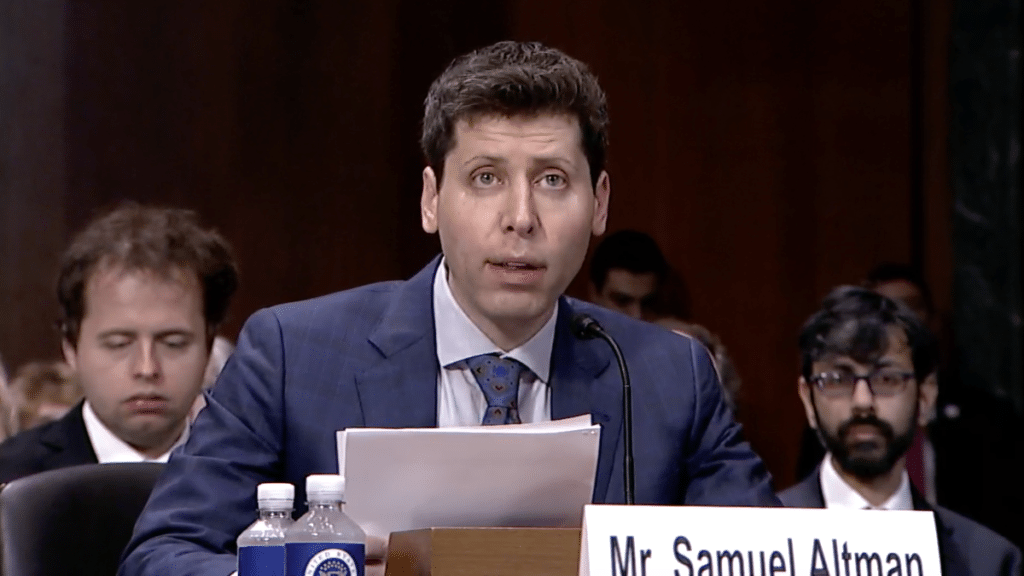

Let me introduce now, the witnesses we're very grateful to you for being here. Sam Altman is the co-founder and CEO of OpenAI, the AI research and deployment company behind ChatGPT and Dall-E. Mr. Altman was president of the early stage startup accelerator Y Combinator from 1914, I'm sorry, 2014 to 2019. OpenAI was founded in 2015. Christina Montgomery is IBM's vice president and Chief Privacy and Trust officer overseeing the company's global privacy program, policies, compliance, and strategy. She also chairs IBM's AI ethics board, a multidisciplinary team responsible for the governance of AI and emerging technologies. Christina has served in various roles at IBM, including corporate secretary to the company's board of directors. She's a global leader in AI ethics and governments. And Ms. Montgomery also is a member of the United States Chamber of Commerce AI Commission and the United States National AI Advisory Committee, which was established in 2022 to advise the president and the National AI Initiative Office on a range of topics related to AI.

Gary Marcus is a leading voice in artificial intelligence. He's a scientist, bestselling author and entrepreneur, founder of the Robust AI and Geometric AI acquired by Uber, if I'm not mistaken, and emeritus Professor of Psychology and neuroscience at NYU. Mr. Marcus is well known for his challenges to contemporary AI, anticipating many of the current limitations decades in advance and for his research in human language development and cognitive neuroscience. Thank you for being here.

And as you may know, our custom on the Judiciary Committee is to swear in our witnesses before they testify. So if you would all please rise and raise your right hand, you solemnly swear that the testimony that you are going to give is the truth, the whole truth, nothing but the truth, so help you God. Thank you Mr. Altman. We're gonna begin with you if that's okay.

Sam Altman:

Thank you, Chairman Blumenthal, Ranking Member Hawley, members of the Judiciary Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today about large neural networks. It's really an honor to be here even more so in the moment than I expected. My name is Sam Altman. I'm the Chief Executive Officer of OpenAI. OpenAI was founded on the belief that artificial intelligence has the potential to improve nearly every aspect of our lives, but also that it creates serious risks. We have to work together to manage. We're here because people love this technology. We think it can be a printing press moment. We have to work together to make it so. OpenAI is an unusual company, and we set it up that way because AI is an unusual technology. We are governed by a nonprofit, and our activities are driven by our mission and our charter, which commit us to working to ensure that the broad distribution of the benefits of AI and to maximizing the safety of AI systems.

We are working to build tools that one day can help us make new discoveries and address some of humanity's biggest challenges like climate change and curing cancer. Our current systems aren't yet capable of doing these things, but it has been immensely gratifying to watch many people around the world get so much value from what these systems can already do today. We love seeing people use our tools to create, to learn to be more productive. We're very optimistic that they're going to be fantastic jobs in the future, and that current jobs can get much better. We also love seeing what developers are doing to improve lives. For example, be My Eyes, used our new multimodal technology in GPT-4 to help visually impaired individuals navigate their environment.

We believe that the benefits of the tools we have deployed so far vastly outweigh the risks, but ensuring their safety is vital to our work. And we make significant efforts to ensure that safety is built into our systems at all levels. Before releasing any new system, OpenAI conducts extensive testing, engages external experts for detailed reviews and independent audits, improves the model's behavior and implements robust safety and monitoring systems. Before we release GPT-4, our latest model, we spent over six months conducting extensive evaluations, external red teaming and dangerous capability testing. We are proud of the progress that we made. GPT-4 is more likely to respond, helpfully and truthfully and refuse harmful requests than any other widely deployed model of similar capability. However, we think that regulatory intervention by governments will be critical to mitigate the risks of increasingly powerful models.

For example, the US government might consider a combination of licensing and testing requirements for development and release of AI models above a threshold of capabilities. There are several other areas I mentioned in my written testimony where I believe that companies like ours can partner with governments, including ensuring that the most powerful AI models adhere to a set of safety requirements, facilitating processes to develop and update safety measures, and examining opportunities for global coordination. And as you mentioned I think it's important that companies have their own responsibility here no matter what Congress does. This is a remarkable time to be working on artificial intelligence, but as this technology advances, we understand that people are anxious about how it could change the way we live. We are too, but we believe that we can and must work together to identify and manage the potential downsides so that we can all enjoy the tremendous upsides. It is essential that powerful AI is developed with democratic values in mind, and this means that US leadership is critical. I believe that we will be able to mitigate the risks in front of us and really capitalize on this technology's potential to grow the US economy and the world's. And I look forward to working with you all to meet this moment, and I look forward to answering your questions. Thank you.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank thank you, Mr. Altman. Ms. Montgomery,

Christina Montgomery:

Chairman Blumenthal Ranking Member Hawley and members of the subcommittee, thank you for today's opportunity to present. AI is not new, but it's certainly having a moment. Recent breakthroughs in generative AI and the technology's dramatic surge in the public attention has rightfully raised serious questions at the heart of today's hearing. What are AI's potential impacts on society? What do we do about bias? What about misinformation, misuse, or harmful content generated by AI systems? Senators? These are the right questions, and I applaud you for convening today's hearing to address them head on. Well, AI may be having its moment. The moment for government to play a role has not passed us by this period of focused public attention on AI is precisely the time to define and build the right guardrails to protect people and their interests. But at its core, AI is just a tool, and tools can servee different purposes.

To that end, IBM urges Congress to adopt a precision regulation approach to ai. This means establishing rules to govern the deployment of AI in specific use cases, not regulating the technology itself. Such an approach would involve four things. First, different rules for different risks. The strongest regulation should be applied to use cases with the greatest risks to people and society. Second, clearly defining risks. There must be clear guidance on AI uses or categories of AI supported activity that are inherently high risk. This common definition is key to enabling a clear understanding of what regulatory requirements will apply in different use cases and contexts. Third, be transparent. So AI shouldn't be hidden. Consumers should know when they're interacting with an AI system and that they have recourse to engage with a real person should they so desire. No person anywhere should be tricked into interacting with an AI system.

And finally, showing the impact. For higher risk use cases, companies should be required to conduct impact assessments that show how their systems perform against tests for bias and other ways that they could potentially impact the public. And to attest that they've done so by following risk-based use case-specific approach. At the core of precision regulation, Congress can mitigate the potential risk of AI without hindering innovation. But businesses also play a critical role in ensuring the responsible deployment of AI companies active in developing or using AI must have strong internal governance, including among other things, designating a lead AI ethics official responsible for an organization's trustworthy AI strategy, standing up an ethics board, or a similar function as a centralized clearinghouse for resource resources to help guide implementation of that strategy. IBM has taken both of these steps and we continue calling on our industry peers to follow suit.

Our AI ethics board plays a critical role in overseeing internal AI governance processes, creating reasonable guardrails to ensure we introduce technology into the world in a responsible and safe manner. It provides centralized governance and accountability while still being flexible enough to support decentralized initiatives across IBM's global operations. We do this because we recognize that society grants our license to operate. And with ai, the stakes are simply too high. We must build, not undermine the public trust. The era of AI cannot be another era of move fast and break things, but we don't have to slam the brakes on innovation either. These systems are within our control today, as are the solutions. What we need at this pivotal moment is clear, reasonable policy and sound guardrails. These guardrails should be matched with meaningful steps by the business community to do their part. Congress and the business community must work together to get this right. The American people deserve no less. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to your questions.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you. Professor Marcus.

Gary Marcus:

Thank you, Senators. Today's meeting is historic. I'm profoundly grateful to be here. I come as a scientist, someone who's founded AI companies and is someone who genuinely loves ai, but who is increasingly worried. There are benefits, but we don't yet know whether they will outweigh the risks. Fundamentally, these new systems are going to be destabilizing. They can and will create persuasive lies at a scale humanity has never seen before. Outsiders will use them to affect our elections, insiders to manipulate our markets and our political systems. Democracy itself is threatened. Chatbots will also clandestinely shape our opinions, potentially exceeding what social media can do. Choices about data sets that AI companies use will have enormous unseen influence. Those who choose the data will make the rules shaping society in subtle but powerful ways. There are other risks, too many stemming from the in, from the inherent unreliability of current systems.

A law professor, for example, was accused by a chatbot of sexual harassment untrue. And it pointed to a Washington Post article that didn't even exist. The more that that happens, the more that anybody can deny anything. As one prominent lawyer told me on Friday, defendants are starting to claim that plaintiffs are making up legitimate evidence. These sorts of allegations undermine the abilities of juries to decide what or who to believe and contribute to the undermining of democracy. Poor medical advice could have serious consequences to an open source large language model recently seems to have played a role in a person's decision to take their own life. The large language model asked the human, if you wanted to die, why didn't you do it earlier? And then followed up with, were you thinking of me? When you overdosed without ever referring the patient to the human health?

That was obviously needed. Another system rushed out and made available to millions of children. Told a person posing as a 13 year old had a lie to her parents about a trip with a 31 year old man. Further threats continue to emerge regularly. A month after GPT-4 was released, OpenAI released ChatGPT plug-ins, which quickly led others to develop something called AutoGPT. With direct access to the internet, the ability to write source code and increased powers of automation, this may well have drastic and difficult to predict security consequences. What criminals are gonna do here is to create counterfeit people. It's hard to even envision the consequences of that. We have built machines that are like bulls in a China shop, powerful, reckless, and difficult to control. We all more or less agrees on the values we would like for our AI systems to honor.

We want, for example, for our systems to be transparent, to protect our privacy, to be free of bias and above all else to be safe. But current systems are not in line with these values. Current systems are not transparent. They do not adequately protect our privacy, and they continue to perpetuate bias, and even their makers don't entirely understand how they work. Most of all, we cannot remotely guarantee that they're safe. And hope here is not enough. The big tech company's preferred plan boils down to trust us. But why should we? The sums of money at stake are mind boggling. Emissions drift, OpenAI's original mission statement proclaimed our goal is to advance AI in the way that most is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return. Seven years later, they're largely beholden to Microsoft, embroiled in part an epic battle of search engines that routinely make things up.

And that's forced Alphabet to rush out products and de-emphasize safety. Humanity has taken a backseat. AI is moving incredibly fast with lots of potential, but also lots of risks. We obviously need government involved and we need the tech companies involved, both big and small. But we also need independent scientists, not just so that we scientists can have a voice, but so that we can participate directly in addressing the problems in evaluating solutions. And not just after products are released, but before, and I'm glad that Sam mentioned that We need tight collaboration between independent scientists and governments in order to hold the company's feet to the fire, allowing independent access to these sys independent scientists, allowing independent scientists access to these systems before they are widely released as part of a clinical trial. Like safety evaluation is a vital first step. Ultimately, we may need something like cern Global, international and neutral, but focused on AI safety rather than high energy physics. We have unprecedented opportunities here, but we are also facing a perfect storm of corporate irresponsibility, widespread deployment, lack of adequate regulation, and inherent unreliability. AI is among the most world-changing technologies ever already changing things more rapidly than almost any technology in history. We acted too slowly with social media. Many unfortunate decisions got locked in with lasting consequence. The choices we make now will have lasting effects for decades, maybe even centuries. The very fact that we are here today in bipartisan fashion to discuss these matters gives me some hope. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thanks very much, professor Marcus. We're gonna have seven minute rounds of questioning, and I will begin. First of all professor Marcus, we are here today because we do face that perfect storm. Some of us might characterize it more like a bomb in a China shop, not a bull. And as Senator Hawley indicated, there are precedents here, not only the atomic warfare era, but also the genome project, the research on genetics where there was international cooperation as a result. And we wanna avoid those past mistakes. As I indicated in my opening statement that were committed on social media that is precisely the reason we are here today. ChatGPT makes mistakes. All AI does, and it can be a convincing liar, what people call hallucinations. That might be an innocent problem in the opening of a judiciary subcommittee hearing where a voice is impersonated, mine in this instance, or quotes from research papers that don't exist, but ChatGPT and Bard are willing to answer questions about life or death matters, for example, drug interactions.

And those kinds of mistakes can be deeply damaging. I'm interested in how we can have reliable information about the accuracy and trustworthiness of these models and how we can create competition and consumer disclosures that reward greater accuracy. The National Institutes of Standards and technology actually already has an AI accuracy test, the face recognition vendor test. It doesn't solve for all the issues with facial recognition, but the scorecard does provide useful information about the capabilities and flaws of these systems. So there's work on models to assure accuracy and integrity. My question lemme begin with you Mr. Altman, is should we consider independent testing labs to provide scorecards and nutrition labels or the equivalent of nutrition labels packaging that indicates to people whether or not the content can be trusted, what the ingredients are, and what the garbage going in may be, because it could result in garbage going out?

Sam Altman:

Yeah, I think that's a great idea. I think that companies should put their own sort of, you know, hear the results of our test, of our model before we release it. Here's where it has weaknesses, here's where it has strengths but also independent audits for that are, are very important. These models are getting more accurate over time. You know, this is, this is as we have, I think said as loudly as anyone, this technology is in its early stages. It definitely still makes mistakes. We find that people, that users are, are pretty sophisticated and understand where the mistakes are that they need or likely to be, that they need to be responsible for verifying what the models say, that they go off and check it. I worry that as the models get better and better the users can have sort of less and less of their own discriminating thought process around it. But, but I think users are more capable than we give often, give them credit for in, in conversations like this. I think a lot of disclosures, which if you've used ChatGPT, you'll see about the inaccuracies of the model are also important. And I am, I'm excited for a world where companies publish with the models information about how they behave, where the inaccuracies are, and independent agencies or companies provide that as well. I think it's a great idea.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

I alluded in my opening remarks to the jobs issue, the economic effects on employment. I think you have said in fact, and I'm gonna quote, development of superhuman machine intelligence is probably the greatest threat to the continued existence of humanity. End quote. You may have had in mind the effect on, on jobs, which is really my biggest nightmare in the long term. Let me ask you what your biggest nightmare is, and whether you share that concern,

Sam Altman:

Like with all technological revolutions, I expect there to be significant impact on jobs, but exactly what that impact looks like is very difficult to predict. If we went back to the other side of a previous technological revolution, talking about the jobs that exist on the other side you know, you can go back and read books of this. It's what people said at the time. It's difficult. I believe that there will be far greater jobs on the other side of this, and that the jobs of today will get better. I, I think it's important. First of all, I think it's important to understand and think about GPT-4 as a tool, not a creature, which is easy to get confused, and it's a tool that people have a great deal of control over and how they use it. And second, GPT-4 and other systems like it are good at doing tasks, not jobs.

And so you see already people that are using GPT-4 to do their job much more efficiently by helping them with tasks. Now, GPT-4 will I think entirely automate away some jobs, and it will create new ones that we believe will be much better. This happens again, my understanding of the history of technology is one long technological revolution, not a bunch of different ones put together, but this has been continually happening. We, as our quality of life raises and as machines and tools that we create can help us live better lives the bar raises for what we do and, and our human ability and what we spend our time going after goes after more ambitious, more satisfying projects. So there will be an impact on jobs. We try to be very clear about that, and I think it will require partnership between the industry and government, but mostly action by government to figure out how we want to mitigate that. But I'm very optimistic about how great the jobs of the future will be.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you. Let me ask Ms. Montgomery and Professor Marcus for your reactions, those questions as well, Ms. Montgomery,

Christina Montgomery:

On the jobs point? Yeah, I mean, well, it's a hugely important question. And it's one that we've been talking about for a really long time at IBM. You know, we do believe that ai, and we've said it for a long time, is gonna change every job. New jobs will be created. Many more jobs will be transformed and some jobs will transition away. I'm a personal example of a job that didn't exist when I joined IBM. And I have a team of AI governance professionals who are in new roles that we created, you know, as early as three years ago. I mean, they're, they're new and they're growing. So I think the most important thing that we could be doing and can, and should be doing now, is to prepare the workforce of today and the workforce of tomorrow for partnering with AI technologies and using them. And we've been very involved for, for years now in doing that in focusing on skills-based hiring in educating for the skills of the future. Our skills build platform has 7 million learners and over a thousand courses worldwide focused on skills. And we've pledged to train 30 million individuals by 2030 in the skills that are needed for society today.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you, professor Marcus.

Gary Marcus:

May I go back to the first question as well? Absolutely. On, on the subject of nutrition labels. I think we absolutely need to do that. I think that there's some technical challenges in that building proper nutrition labels goes hand in hand with transparency. The biggest scientific challenge in understanding these models is how they generalize. What do they memorize and what new things do they do? The more that there's in the data set, for example, the thing that you want to test accuracy on, the less you can get a proper read on that. So it's important, first of all, that scientists be part of that process. And second, that we have much greater transparency about what actually goes into these systems. If we don't know what's in them, then we don't know exactly how well they're doing when we give something new and we don't know how good a benchmark that will be for something that's entirely novel.

So I could go into that more, but I want to flag that. Second is on jobs past performance history is not a guarantee of the future. It has always been the case in the past that we have had more jobs, that new jobs, new professions come in. As new technologies come in, I think this one's gonna be different. And the real question is over what time scale? Is it gonna be 10 years? Is it gonna be a hundred years? And I don't think anybody knows the answer to that question. I think in the long run, so-called artificial general intelligence really will replace a large fraction of human jobs. We're not that close to artificial general intelligence, despite all of the media hype and so forth. I would say that what we have right now is just small sampling of the AI that we will build in 20 years.

People will laugh at this as I think it was Senator Hawley made but maybe Senator Durbin made the example about this. It was Senator Durbin that made the example about cell phones. When we look back at the AI of today, 20 years ago, will be like, wow, that stuff was really unreliable. It couldn't really do planning, which is an important technical aspect. It's reasoning was ability and reasoning abilities were limited. But when we get to AGI, artificial general intelligence, maybe let's say it's 50 years, that really is gonna have, I think, profound effects on, on labor. And there's just no way around that. And last, I don't know if I'm allowed to do this, but I will note that Sam's worst fear I do not think is employment. And he never told us what his worst fear actually is. And I think it's germane to find out.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you. I'm gonna ask Mr. Altman if he cares to respond.

Sam Altman:

Yeah. Look, we have tried to be very clear about the magnitude of the risks here. I think jobs and employment and what we're all gonna do with our time really matters. I agree that when we get to very powerful systems, the landscape will change. I think I'm just more optimistic that we are incredibly creative and we find new things to do with better tools, and that will keep happening. My worst fears are that we cause significant, we, the field, the technology, the industry cause significant harm to the world. I think that could happen in a lot of different ways. It's why we started the company. It's a big part of why I'm here today and why we've been here in the past and, and we've been able to spend some time with you. I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong. And we want to be vocal about that. We want to work with the government to prevent that from happening, but we try to be very clear-eyed about what the downside case is and the work that we have to do to mitigate that.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thank you. And, and our hope is that the rest of the industry will follow the example that you and IBM, Ms. Montgomery have set by coming today and meeting with us as you have done privately in helping to guide what we're going to do so that we can target the harms and avoid unintended consequences to the good.

Sam Altman:

Thank you.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Senator Hawey,

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Thank you again, Mr. Chairman. Thanks to the witnesses for being here. Mr. Altman, I think you grew up in St. Louis. If I'm, I did not mistaken.

Sam Altman:

I did. It's a great place.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Missouri, here it is. Thank you. I want that noted, especially underlined in the record. Missouri is a great place. That is the takeaway from today's hearing. Maybe we can stop there. Mr. Chairman. Let me ask you Mr. Altman, I think I'll start with you, and I'll just preface this by saying my questions here are an attempt to get my head around and to ask all of you, to help us to get our heads around what these, this generative ai, particularly the large language models, what it can do. So I'm trying to understand its capacities and then its significance. So I'm looking at a paper here entitled "Large Language Models, Trained on Media Diets Can Predict Public Opinion." This is just posted about a month ago. The authors are two, Andreas Anan and Roy, and their conclusion this work was done at MIT and then also at, at Google.

The conclusion is that large language models can indeed predict public opinion. And they go through and, and, and model why this is the case. And they conclude ultimately that an AI system can predict human survey responses by adapting a pre-trained language model to subpopulation specific media diets. In other words, you can feed the model a particular set of, of media inputs, and it can, with remarkable accuracy in the paper, goes into this, predict then what people's opinions will be. I, I'm, I wanna think about this in the context of elections. If these large language models can, even now, based on the information we put into them quite accurately predict public opinion, you know, ahead of time. I mean, predict, it's before you even ask the public these questions, what will happen when entities, whether it's corporate entities or whether it's governmental entities, or whether it's campaigns or whether it's foreign actors, take this survey information, these predictions about public opinion and then fine tune strategies to elicit certain responses, certain behavioral responses.

I mean, we already know this committee is her testimony, I think three years ago now, about the effect of something as prosaic. It now seems as Google search, the effect that this has on voters in an election, particularly undecided voters in the final days of an election, who may try to get information from Google search. And what an enormous effect, the ranking of the Google search, the articles that it returns, has become an enormous effect on an undecided voter. This, of course, is orders of magnitude, far more powerful, far more significant, far more directive if you like. So, Mr. Altman, maybe you can help me understand here what some of the significance of this is. Should we be concerned about models that can, large language models that can predict survey opinion and then can help organizations, entities fine tune strategies to elicit behaviors from voters? Should we be worried about this for our elections?

Sam Altman:

Yeah. thank you Senator Hawley for the question. It's one of my areas of greatest concern. The more general ability of these models to manipulate, to persuade to provide sort of one-on-one you know, interactive disinformation. I think that's like a broader version of what you are talking about, but giving that we're gonna face an election next year and these models are getting better I think this is a significant area of concern. I think there's a lot, there's a lot of policies that companies can voluntarily adopt, and I'm happy to talk about what we do there. I do think some regulation would be quite wise on this topic. Someone mentioned earlier, it's something we really agree with. People need to know if they're talking to an ai, if, if content that they're looking at might be generated or might not.

I think it's a great thing to do is to make that clear. I think we also will need rules, guidelines about what, what's expected in terms of disclosure from a company providing a model that could have these sorts of abilities that you talk about. So I'm nervous about it. I think people are able to adapt quite quickly. When Photoshop came onto the scene a long time ago, you know, for a while people were really quite fooled by photoshopped images and then pretty quickly developed an understanding that images might be photoshopped this will be like that, but on steroids and the, the interactivity the ability to really model, predict humans, well, as you talked about I think is going to require a combination of companies doing the right thing, regulation and public education.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Mr. Professor Marcus, do you wanna address this?

Gary Marcus:

I'd like to add two things. One is in the appendix to my remarks, I have two papers to make you even more concerned. One is in the Wall Street Journal just a couple days ago called "Help. My political beliefs were altered by a chatbot." And I think the scenario you raised was that we might basically observe people and use surveys to figure out what they're saying. But as Sam just acknowledged the risk is actually worse, that the systems will directly maybe not even intentionally manipulate people. And that was the thrust of the Wall Street Journal article. And it links to an article that I've also linked to called Interacting, and it's not yet published. Not yet peer reviewed, "Interacting with opinionated language models changes user views." And this comes back ultimately to data. One of the things that I'm most concerned about with GPT-4 is that we don't know what it's trained on.

I guess Sam knows, but the rest of us do not. And what it is trained on has consequences for essentially the biases of the system. We could talk about that in technical terms, but how these systems might lead people about depends very heavily on what data is trained on them. And so we need transparency about that. And we probably need scientists in there doing analysis in order to understand what the political influences of, for example, of these systems might be. And it's not just about politics. It can be about health, it could be about anything. These systems absorb a lot of data and then what they say reflects that data, and they're gonna do it differently depending on what, what's in that data. So it makes a difference if they're trained on the Wall Street Journal as opposed to the New York Times or, or Reddit. I mean, actually they're largely trained on all of this stuff, but we don't really understand the composition of that. And so we have this issue of potential manipulation, and it's even more complex than that because it's subtle manipulation. People may not be aware of what's going on. That was the point of both the Wall Street Journal article and the other article that I, I called your attention to.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Let me ask you about AI systems trained on personal data. The kind of data that, for instance, the social media companies, the major platforms, Google Meta, et cetera, collect on all of us routinely. And we've had many a chat about this in this committee over many a year now. But the massive amounts of data, personal data that the companies have on each one of us, an AI system that is, that is trained on that individual data, that knows each of us better than ourselves, and also knows the billions of data points about human behavior, human language interaction, generally. Wouldn't we be able, wouldn't we, can't we foresee an AI system that is extraordinarily good at determining what will grab human attention and what will keep an individual's attention? And so, and for the war, for attention, the war for clicks that is currently going on, on all of these platforms, that's how they make their money.

I'm just imagining an AI system. These AI models supercharging that war for attention, such that we now have technology that will allow individual targeting of a kind we have never even imagined before, where the AI will know exactly what Sam Altman finds attention grabbing. We'll know exactly what Josh Hawley finds attention grabbing. We'll be able to elicit, to grab our attention, and then elicit responses from us in a way that we have here before not even been able to imagine. Should we be concerned about that for its corporate applications, for the monetary applications, for the manipulation that that could come from that, Mr. Almond?

Sam Altman:

Yes, we should be concerned about that. To be clear OpenAI does not, we're not off, you know, we wouldn't have an ad-based business model. So we're not trying to build up these profiles of our users. We're not, we're not trying to get them to use it more actually, we'd love it if they use it less cause we don't have enough GPUs. But I think other companies are already and certainly will in the future, use AI models to create, you know, very good ad predictions of what a user will like. I think that's already happening in, in many ways.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO):

Mr. Marcus, anything you wanna add?

Gary Marcus:

Yes. and perhaps Ms. Montgomery will want to too as well. I don't, but hyper targeting of advertising is definitely going to come. I agree that that's not been OpenAI's business model. Of course now they're working for Microsoft and I don't know what's in Microsoft's thoughts. But we will definitely see it. Maybe it will be with open source language models. I, I don't know. But the technology there is, let's say partway there to being able to do that. And we'll certainly get there.

Christina Montgomery:

So we are an enterprise technology company, not consumer focused. So the space isn't one that we necessarily operate in in terms of, but these issues are hugely important issues. And it's why we've been out ahead in developing the technology that will help to ensure that you can do things like produce a fact sheet that has the ingredients of what your data is trained on data sheets, model cards, all those types of things. And calling for, as I've mentioned today, transparency, so you know what the algorithm was trained on. And then you also know and can manage and monitor continuously over the life cycle of an AI model, the behavior and the performance of that model.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Senator Durbin.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

Thank you. I think what's happening today in this hearing room is historic. I can't recall when we've had people representing large corporations or private sector entities come before us and plead with us to regulate them. In fact, many people in the Senate have base their careers on the opposite that the economy will thrive if government gets the hell out of the way. And what I'm hearing instead today is that ‘stop me before I innovate again’ message. And I'm just curious as to how we're going to achieve this. As I mentioned section two 30 in my opening remarks, we learned something there. We decided that in section two 30 that we were basically going to absolve the industry from liability for a period of time as it came into being. Well, Mr. Altman, on the podcast earlier this year, you agreed with host Kara Swisher, that section two 30 doesn't apply to generative ai and that developers like OpenAI should not be entitled to full immunity for harms caused by their products. So what have we learned from two 30 that applies to your situation with ai?

Sam Altman:

Thank you for the question, Senator. I, I don't know yet exactly what the right answer here is. I'd love to collaborate with you to figure it out. I do think for a very new technology, we need a new framework. Certainly companies like ours bear a lot of responsibility for the tools that we put out in the world, but tool users do as well. And how we want and, and also people that will build on top of it between them and the end consumer. And how we want to come up with a liability framework, there is a super important question. And we'd love to work together.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

The point I wanna make is this, when it came to online platforms, the inclination of the government was ‘get out of the way.’ This is a new industry, don't over-regulate it. In fact, give them some breathing space and see what happens. I'm not sure I'm happy with the outcome as I look at online platforms. Me either, and, and the harms that they have created problems that we've seen demonstrated in this committee. Child exploitation, cyber bullying, online drug sales, and more. I don't wanna repeat that mistake again. And what I hear is the opposite suggestion from the private sector and that is come in, in the front end of this thing and establish some liability standards, precision regulation for a major company like I B M to come before this committee and say to the government, please regulate us. Can you explain the difference in thinking from the past and now?

Christina Montgomery:

Yeah, absolutely. So for us, this comes back to the issue of trust and trust in the technology. Trust is our license to operate, as I mentioned in my remarks. And so we firmly believe in, we've been calling for precision regulation of artificial intelligence for years now. This is not a new position. We think that technology needs to be deployed in a responsible and clear way that people, we've taken principles around that trust and transparency, we call them, are principles that were articulated years ago and build them into practices. That's why we're here advocating for precision regulatory approach. So we think that AI should be regulated at the point of risk, essentially, and that's the point at which technology meets society.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

Let's take a look at what that might appear to be. Members of Congress are pretty smart. A lot of people maybe not as smart as we think we are many times, and government certainly has a capacity to do amazing things. But when you talk about our ability to respond to the current challenge and perceive the future challenges, which you all have described in terms which are hard to forget, as you said, Mr. Altman, things can go quite wrong. As you said, Mr. Marcus, democracy is threatened. I mean, the magnitude of the challenge you're giving us is substantial. I'm not sure that we respond quickly and with enough expertise to deal with it. Professor Marcus, you made a reference to cern, the International Arbiter of nuclear research, I suppose, I dunno if that's a fair characterization, but it's a characterization. I'll start with what is it, what agency of this government do you think exists that could respond to the challenge that you've laid down today?

Gary Marcus:

We have many agencies that can respond in some ways. For example, the FTC, the FCC, there are many agencies that can, but my view is that we probably need a cabinet level organization within the United States in order to address this. And my reasoning for that is that the number of risks is large. The amount of information to keep up on is so much. I think we need a lot of technical expertise. I think we need a lot of coordination of these efforts. So there is one model here where we stick to only existing law and try to shape all of what we need to do. And each agency does their own thing. But I think that AI is gonna be such a large part of our future and is so complicated and moving so fast. And this does not fully solve your problem about a dynamic world. But it's a step in that direction to have an agency that's full-time job is to do this. I personally have suggested in fact that we should want to do this at a global way. I wrote an article in The Economist, I have a link in here an invited essay for The Economist suggesting we might want an international agency for AI.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

Well, that's the point I wanted to go to next, and that is the fact that I'll get it aside from the CERN and nuclear examples, because government was involved in that from day one, at least in the United States. Yes. But now we're dealing with innovation which doesn't necessarily have a boundary. That's correct. We may create a great US agency, and I hope that we do that may have jurisdiction over US corporations and US activity, but doesn't have a thing to do with what's going to bombard us from outside the United States. How do you give this international authority, the authority to regulate in a fair way for all entities involved in AI?

Gary Marcus:

I think that's probably over my pay grade. I would like to see it happen and I think it may be inevitable that we push there. I mean, I, I think the politics behind it are obviously complicated. I'm really heartened by the degree to which this room is bipartisan and, and supporting the same things. And that makes me feel like it might be possible. I, I would like to see the United States take leadership in such organization. It has to involve the whole world and not just the US to work properly. I think even from the perspective of the companies, it would be a good thing. So the companies themselves do not want a situation where you take these models, which are expensive to train, and you have to have 190, some of them you know, one for every country that that wouldn't be a good way of operating.

When you think about the energy costs alone, just for training these systems, it would not be a good model if every country has its own policies and each, for each jurisdiction, every company has to train another model. And maybe you know, different states are different. So Missouri and California have different rules. And so then that requires even more training of these expensive models with huge climate impact. And I mean, just, it would be very difficult for the companies to operate if there was no global coordination. And so I think that we might get the companies on board if there's bipartisan support here. And I think there's support around the world that is entirely possible that we could develop such a thing. But obviously there are many, you know, nuances here of diplomacy that are over my pay grade. I hope I would love to learn from you all to try to help make that happen.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL):

Mr. Altman.

Sam Altman:

Can I weigh in just briefly? Briefly, please. I want to echo support for what Mr. Marcus said. I think the US should lead here and do things first, but to be effective we do need something global. As you mentioned, this can, this can happen everywhere. There is precedent. I know it sounds naive to call for something like this, and it sounds really hard. There is precedent. We've done it before with the IAEA. We've talked about doing it for other technologies. They're given what it takes to make these models: the chip supply chain, the sort of limited number of competitive GPUs, the power the US has over these companies. I think there are paths to the US setting some international standards that other countries would need to collaborate with and be part of that are actually workable, even though it sounds on its face, like an impractical idea. And I think it would be great for the world. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thanks, Senator Durbin. And in fact I think we're going to hear more about what Europe is doing. The European Parliament already is acting on an AI act on social media. Europe is ahead of us. We need to be in the lead. I think your, your point is very well taken. Let me turn to Senator Graham, Senator Blackburn.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

And thank you, Mr. Chairman, and thank you all for being here with us today. I put into my chat, GPT account should Congress regulate AI chat, GPT, and it gave me four, four cons and says, ultimately the decision rests with Congress and deserves careful consideration. So on that reasonable, you know, it was very balanced. I recently visited with the Nashville Technology Council. I represent Tennessee. And of course, you had people there from healthcare, financial services, logistics, educational entities, and they're concerned about what they see happening with ai, with the utilizations for their companies. Ms. Montgomery, you know, sim similar to you, they've got healthcare people are looking at disease analytics. They're looking at predictive diagnosis, how this can better the outcomes for patients, logistics industry, looking at ways to save time and money and yield efficiencies. You've got financial services that are saying, how does this work with Quantum?

How does it work with blockchain? How can we use this? But it, I think as we have talked with them, Mr. Chairman, one of the things that continues to come up is yes professor Marcus, as you were saying, the eu different entities are ahead of us in this, but we have never established a federally preempt given preemption for online privacy, for data security, and put some of those foundational elements in place, which is something that we need to do as we look at this. And it will require that Commerce committee, judiciary committee decide how we move forward so that people own their virtual you. And Mr. Altman, I was glad to see last week that your OpenAI models are not going to be trained using consumer data. I think that that is important. And if we have a second round, I've got a host of questions for you on data security and privacy.

But I think it's important to let people control their virtual you, their information in these settings. And I wanna come to you on music and content creation, because we've got a lot of songwriters and artists. Yeah. And a, I think we have the best creative community on the face of the Earth. They're in Tennessee, and they should be able to decide if their copyrighted songs and images are going to be used to train these models. And I'm concerned about OpenAI's jukebox. It offers some renditions in the style of Garth Brooks, which suggests that OpenAI is trained on Garth Brooks songs. I went in this weekend and I said, write me a song that sounds like Garth Brooks. And it gave me a different version of Simple Man. So it's interesting that it would do that. But you're training it on these copyrighted songs, these mini files, these sound technologies. So as you do this, who owns the rights to that AI generated material and using your technology, could I remake a song, insert content from my favorite artist, and then own the creative right to that song?

Sam Altman:

Thank you, Senator. This is an area of great interest to us. I would say, first of all, we think that creators deserve control over how their creations are used and what happens sort of beyond the point of, of them releasing it into the world. Second, I think that we need to figure out new ways with this new technology that creators can win, succeed, have a vibrant life. And I'm optimistic that this will present it.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Then, then let me ask you this. How do you compensate the art, the artist?

Sam Altman:

That's exactly what I was gonna say. Okay. we'd like to, we're working with the artists now, visual artists, musicians to figure out what people want there. There's a lot of different opinions, unfortunately. And at some point we'll have,

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Okay, let me ask you this. Do you favor something like sound exchange that has worked in the area of, or radio?

Sam Altman:

I'm not familiar with sound exchange. I'm sorry.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Streaming. Okay. You've got your team behind you. Get back to me on that. That would be a third party entity. Okay. So let's discuss that. Let me move on. Can you commit, as you've done with Consumer Data, not to train chat, GPT, OpenAI Jukebox or other AI models on artists and songwriters copyrighted works, or use their voices and their likenesses without first receiving their consent?

Sam Altman:

So first of all, jukebox is not a product we offer. That was a research release, but it's not, you know, unlike ChatGPT or DALLE. But….

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

We've lived through Napster.

Sam Altman:

Yes. But we're…

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

That was something that really cost a lot of artists, a lot of money.

Sam Altman:

Oh, I understand. Yeah, for sure.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

In the digital distribution era.

Sam Altman:

I don't know the numbers on jukebox on the top of my head as a research release. I can, I can follow up with your office, but it's not, jukebox is not something that gets much attention or usage. It was put out to, to show that something's possible.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Well, Senator Durbin just said, you know, and I think it's a fair warning to you all if we are not involved in this from the get-go, and you all already are a long way down the path on this, but if we don't step in, then this gets away from you. So are you working with a copyright office? Are you considering protections for content generators and creators in generative ai?

Sam Altman:

Yes, we are absolutely engaged on that. Again, to reiterate my earlier point, we think that content creators, content owners, need to benefit from this technology exactly what the economic model is. We're still talking to artists and content owners about what they want. I think there's a lot of ways this can happen, but very clearly, no matter what the law is, the right thing to do is to make sure people get significant upside benefit from this new technology. And we believe that it's really going to deliver that. But that content owners likenesses people totally deserve control over how that's used and to benefit from it.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Okay. So on privacy then, how do you plan to account for the collection of voice and other user specific data, things that are copyright righted user specific data through your AI applications? Because if I can go in and say, write me a song that sounds like Garth Brooks and it takes part of an existing song, there has to be a compensation to that artist for that utilization and that use, if it was radio play, it would be there. If it was streaming, it would be there. So if you are going to do that, what is your policy for making certain, you're accounting for that and you're protecting that individual's right. To privacy and their right to secure that data and that created work.

Sam Altman:

So a few thoughts about this. Number one, we think that people should be able to say, I don't want my personal data trained on. That's, I think that's right.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

That gets to a national privacy law, which many of us here on the dais are working toward getting something that we can use.

Sam Altman:

Yeah, I think strong privacy…

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

And my time's expired. Let me yell back. Thank you, Mr. Chair.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Thanks, Senator Blackburn. Senator Klobuchar.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman. and Senator Blackburn, I love Nashville. Love Tennessee, love your music. But I will say I use ChatGPT and just asked, what are the top creative song artists of all time? And two of the top three were from Minnesota <laugh>, that would be Prince, and...

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN):

Sure....

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Prince and Bob Dylan. Okay. All right. So let us, let us continue on.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

One thing AI won't change, and you're seeing it here.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

All right. So on a more serious note though my staff and I in my role as chair of the Rules committee and leading a lot of the election bill, and we just introduced a bill that's Representative Yvette Clark from New York, introduced over in the House, Senator Booker and Bennett and I did on political advertisements. But that is just of course, the tip of the iceberg. You know, this from your discussions with Senator Hawley and others about the images and my own view it's Senator Grahams of Section two 30, is that we just can't let people make stuff up and then not have any consequence. But I'm gonna focus in on what my job, one of my jobs will be on the rules committee. And that is election misinformation. And we just asked Chad GPT to do a tweet about a polling location in Bloomington, Minnesota, and said, there are long lines at this polling location at Atonement Lutheran Church.

Where should we go now? Albeit it's not an election right now, but the answer, the tweet that was drafted was a completely fake thing. Go to 1 2 34 Elm Street. And so you can imagine what I'm concerned about here with an election upon us with primary elections upon us, that we're gonna have all kinds of misinformation. And I just wanna know what you're planning on doing it, doing about it. I know we're gonna have to do something soon, not just for the images of the candidates, but also for misinformation about the actual polling places and election rules.

Sam Altman:

Thank you, Senator. We talked about this a little bit earlier. We are quite concerned about the impact this can have on elections. I think this is an area where hopefully the entire industry and the government can work together quickly. There's, there's many approaches, and I'll talk about some of the things we do, but before that, I think it's tempting to use the frame of social media. But this is not social media. This is different. And so the, the, the response that we need is different. You know, th this is a tool that a user is using to help generate content more efficiently than before. They can change it. They can test the accuracy of it. If they don't like it, they can get another version. But it still then spreads through social media or other ways like chat. G B T is a, you know, single player experience where, where you're just using this. And so I think as we think about what to do, that's, that's important to understand that there's a lot that we can and do, do there. There's things that the model refuses to generate. We have policies. We also importantly have monitoring. So at scale we can detect someone generating a lot of those tweets. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, even if generating one tweet is okay.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Yeah. And of course, there's gonna be other platforms. And if they're all spouting out fake election information, I just, I think what happened in the past with Russian interference and like, it's just gonna be a tip of the iceberg Yeah. When some of those fake ads. So that's number one. Number two is the impact on intellectual property. And Senator Blackburn was getting at some of this with song rights and had serious concerns about that. But news content so Senator Kennedy and I have a bill that was really quite straightforward, that would simply allow the news organizations an exemption to be able to negotiate with basically Google and Facebook. Microsoft was supportive of the bill, but basically negotiated with them to get better rigged and be able to not have some leverage.

And other countries are doing this, Australia and the like. And so my question is, when we already have a study by Northwestern predicting that one-third of the US newspapers are that roughly existed, two decades are gonna go, are gonna be gone by 2025, unless you start compensating for everything from book movies, books. Yes. but also news content. We're gonna lose any realistic content producers. And so I'd like your response to that. And of course, there is an exemption for copyright in section two 30. But I think asking little newspapers to go out and sue all the time just can't be the answer. They're not gonna be able to keep up.

Sam Altman:

Yeah. Like, it is my hope that tools like what we're creating can help news organizations do better. I think having a vibrant, having a vibrant national media is critically important. And let's call it round one of the internet has not been great for that.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Right. we're talking here about local that, you know, report on your high school for sure. Football scores and a scandal in your city council, those kinds of things. For sure. They're the ones that are actually getting the worse, the little radio stations and broadcast. But do you understand that this could be exponentially worse in terms of local news content if they're not compensated

Sam Altman:

Well...

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Because what they need is to be compensated for their content and not have it stolen.

Sam Altman:

Again, our model, you know, our, the current version of GPT-4 ended to training in 2021. It's not, it's not, it's not a good way to find recent news. And it's, I don't think it's a service that can do a great job of linking out, although maybe with our plugins, it's, it's possible. If there are things that we can do to help local news, we would certainly like to, again, I think it's critically important. Okay.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

One last… yeah.

Gary Marcus:

May I add something there?

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Yeah. But let me just ask you a question. You can combine 'em quick. More transparency on the platforms. Senator Coons and Senator Cassidy and I have the Platform Accountability Transparency Act to give researchers access to this information of the algorithms and the, like on social media data. Would that be helpful? And then why don't you just say yes or no and then go at his the

Gary Marcus:

Transparency is absolutely critical here to understand the political ramifications, the bias ramifications, and so forth. We need transparency about the data. We need to know more about how the models work. We need to have scientists have access to them. I was just gonna amplify your earlier point about local news. A lot of news is going to be generated by these systems. They're not reliable. News guard already is a study, I'm sorry, it's not in my appendix, but I will get it to your office. Showing that something like 50 websites are already generated by bots. We're gonna see much, much more of that, and it's gonna make it even more competitive for the local news organizations. And so the quality of the sort of overall news market is going to decline as we have more generated content by systems that aren't actually reliable in the content they're generated.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN):

Thank you. And thank you on a very timely basis to make the argument why we have to mark up this bill again in June. I appreciate it. Thank you.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT):

Senator Graham.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and Senator Hawley for having this. I'm trying to find out how it is different than social media and learn from the mistakes we made with social media. The idea of not suing social media companies is to allow the internet to flourish. Because if I slander you you can sue me. If you're a billboard company and you put up the slander, can you sue the billboard company? We said no. Basically, section two 30 is being used by social media companies to high, to avoid liability for activity that other people generate. When they refuse to comply with their terms of use, a mother calls up the company and says, this app is being used to bully my child to death. You promise, in the terms of use, she would prevent bullying. And she calls three times, she gets no response, the child kills herself and they can't sue. Do you all agree we don't wanna do that again?

Sam Altman:

Yes.

Gary Marcus:

If I may speak for one second, there's a fundamental distinction between reproducing content and generating content.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Yeah. But you, you would like liability where people are harmed.

Gary Marcus:

Absolutely.

Christina Montgomery:

Yes. In fact, IBM has been publicly advocating to condition liability on a reasonable care standard.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Sure. So let me just make sure I understand the law as it exists today. Mr. Altman, thank you for coming. Your company is not claiming that Section 230 applies the tool you have created.

Sam Altman:

Yeah. We're claiming we need to work together to find a totally new approach. I don't think Section 230 is the even the right framework.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Okay. So under the law it exists today. This tool you create, if I'm harmed by it, can I sue you?

Sam Altman:

That is beyond my area of legal...

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Have you ever been sued?

Sam Altman:

Not for that, no.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Have you ever been sued at all? Your company?

Sam Altman:

Yeah.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

OpenAI gets sued, huh?

Sam Altman:

Yeah, we've gotten sued before.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Okay. And what for?

Sam Altman:

I mean, they've mostly been like pretty frivolous things, like, I think happens to any company,

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

But like the examples my colleagues have given from artificial intelligence that could literally ruin our lives. Can we go to the company that created that tool and sue 'em? Is that your understanding?

Sam Altman:

Yeah. I think there needs to be clear responsibility by the company's.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

But you're not claiming any kind of legal protection like section two, that two 30 applies to your industry, is that correct?

Sam Altman:

No, I don't think we're, I don't, I don't think we're saying anything like that.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

Mr. Marcus? When it comes to consumers, there seems to be like three time tested ways to protect consumers against any product. Statutory schemes, which are nonexistent here. Legal systems, which may be app here, but not social media and agencies. Go back to Senator Hawley. The Adam Bomb is put a cloud over humanity, but nuclear power could be one of the solutions to climate change. So what I'm trying to do is make sure that you just can't go build a nuclear power plant. Hey Bob, what would you like to do today? Let's go build a nuclear power plant. You have a nuclear regulatory commission that governs how you build a plant and is licensed. Do you agree, Mr. Altman, that these tools you're creating should be licensed?

Sam Altman:

Yeah. We've been calling for this. We think any…

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

That's the simplest way you get a license. And do you agree with me that the simplest way and the most effective way is have an agency that is more nimble and smarter than Congress, which should be easy to create overlooking what you do? Yes.

Sam Altman:

We'd be enthusiastic about that.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

You agree with that, Mr. Marcus?

Gary Marcus:

Absolutely.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC):

You agree with that, Ms. Montgomery?

Christina Montgomery:

I would have some nuances. I think we need to build on what we have in place already today.